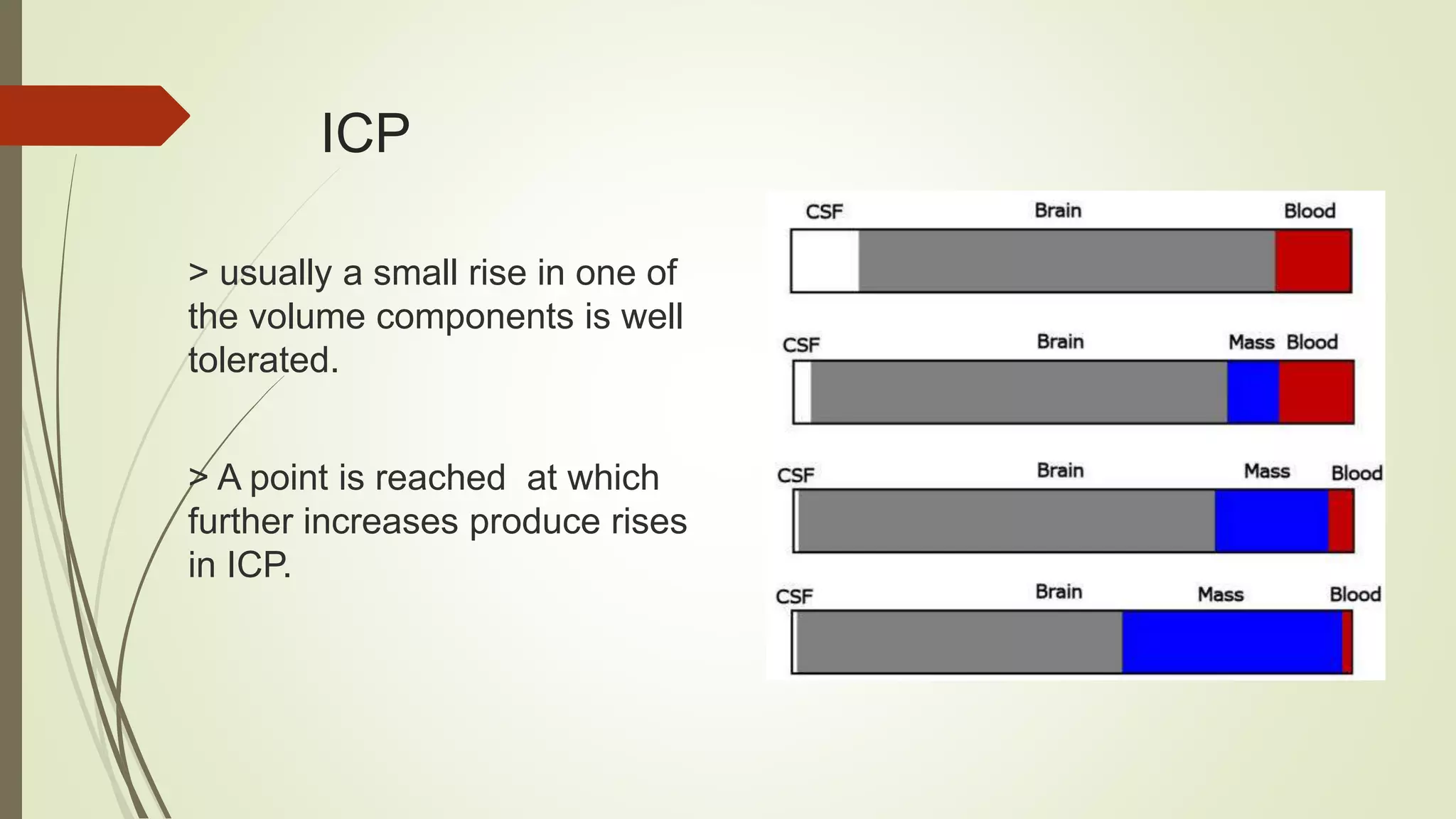

This document discusses various topics related to intracranial hemorrhage including terminology, intracerebral hemorrhage, intracranial pressure, cerebral blood flow, cerebral perfusion pressure, management goals, preventing hematoma expansion through blood pressure control and anticoagulant reversal, intracranial pressure management, surgery considerations, medical care, post-stroke seizures, and reperfusion therapy for ischemic stroke.

![Hemodynamic and fluid management

Approximately 80 % of AIS patients are hypertensive [ SBP>140 mmHg] at

presentation.

Severe hypertension likely contributes to cardiorespiratory complications and

promotes cytotoxic edema and hemorrhagic transformation

There is a U-shaped relationship between BP and outcome after AIS, with both

high and low BP having adverse effects on outcome

Although high BP is independently associated with poor outcome after AIS, the

effect of acute blood pressure lowering is not clear. Some studies suggest improved,

some unchanged , and others worsened long-term outcomes.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/intracerebralhemorrhagesahischemicstroke412-230303063307-468e029c/75/Intracerebral-hemorrhage-SAH-ischemic-stroke-412-pptx-46-2048.jpg)