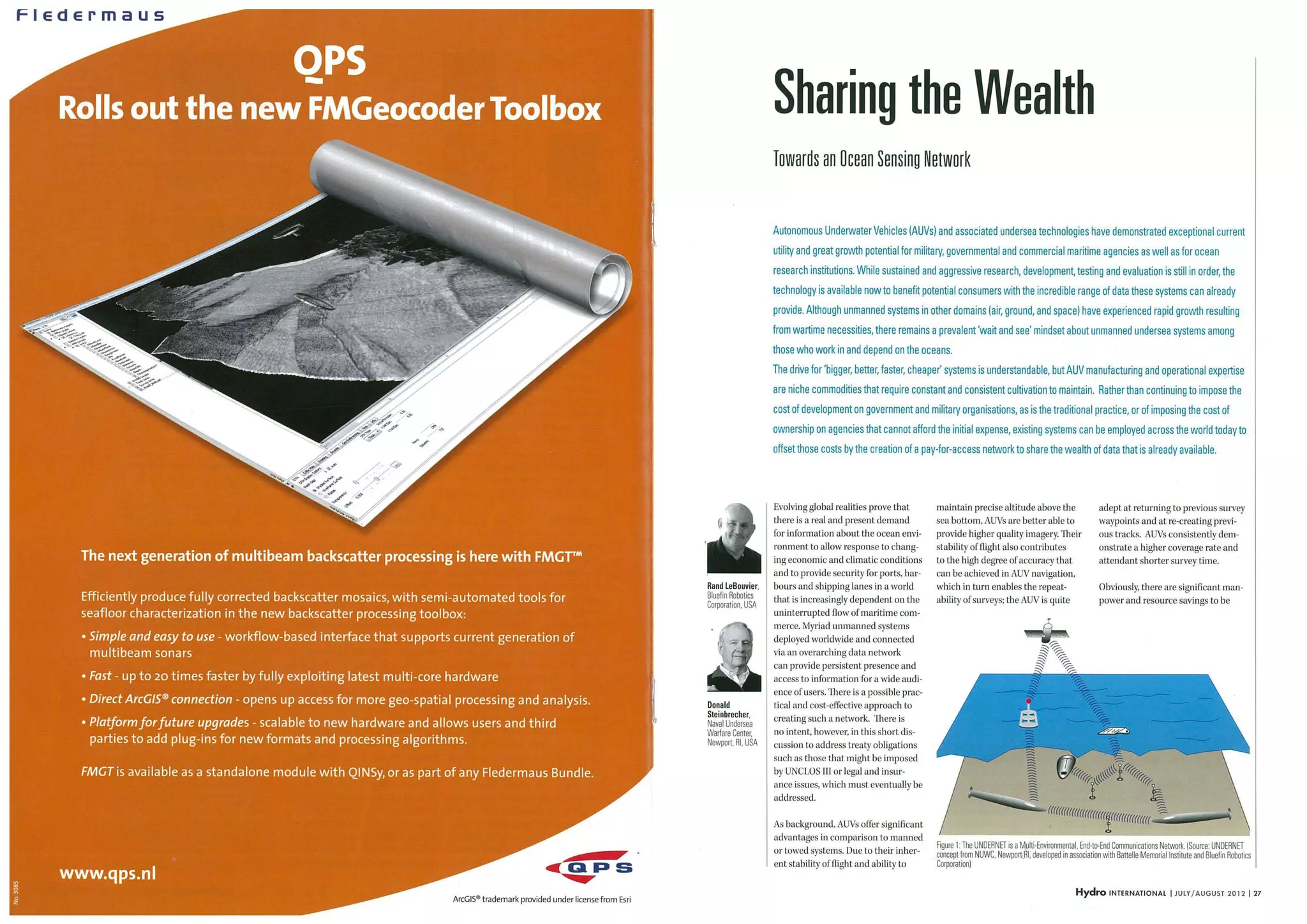

The document discusses the vision and implementation of an ocean sensing network called UNDERNET. It proposes a system of autonomous underwater and surface vehicles connected via satellite networks that can collect and share ocean data on a pay-for-access basis. This would help offset the high costs of developing, operating, and maintaining unmanned maritime systems, while providing widespread access to valuable ocean data. The network aims to make fresh, high-quality data accessible and tailorable to a broad audience for applications like port security, offshore energy, and military operations.