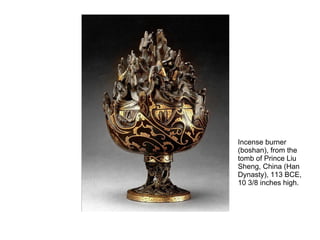

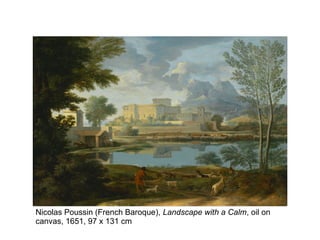

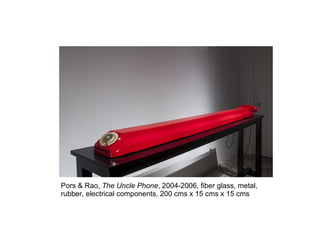

This document provides an overview of the relationship between humans, nature, and art in various cultures and time periods. It discusses how in Daoist and Chinese Han Dynasty art, nature and achieving immortality were closely linked. It then covers the emergence of landscape art in 17th century Europe, focusing on classical landscapes that depicted an idealized nature. The document moves onto impressionist and modern depictions of nature, and how photography impacted landscape painting. It concludes with examples of contemporary art that explore the boundaries between nature and technology. The document examines art from various cultures and eras to trace the evolving relationship between humans, nature, and technology in creative works.