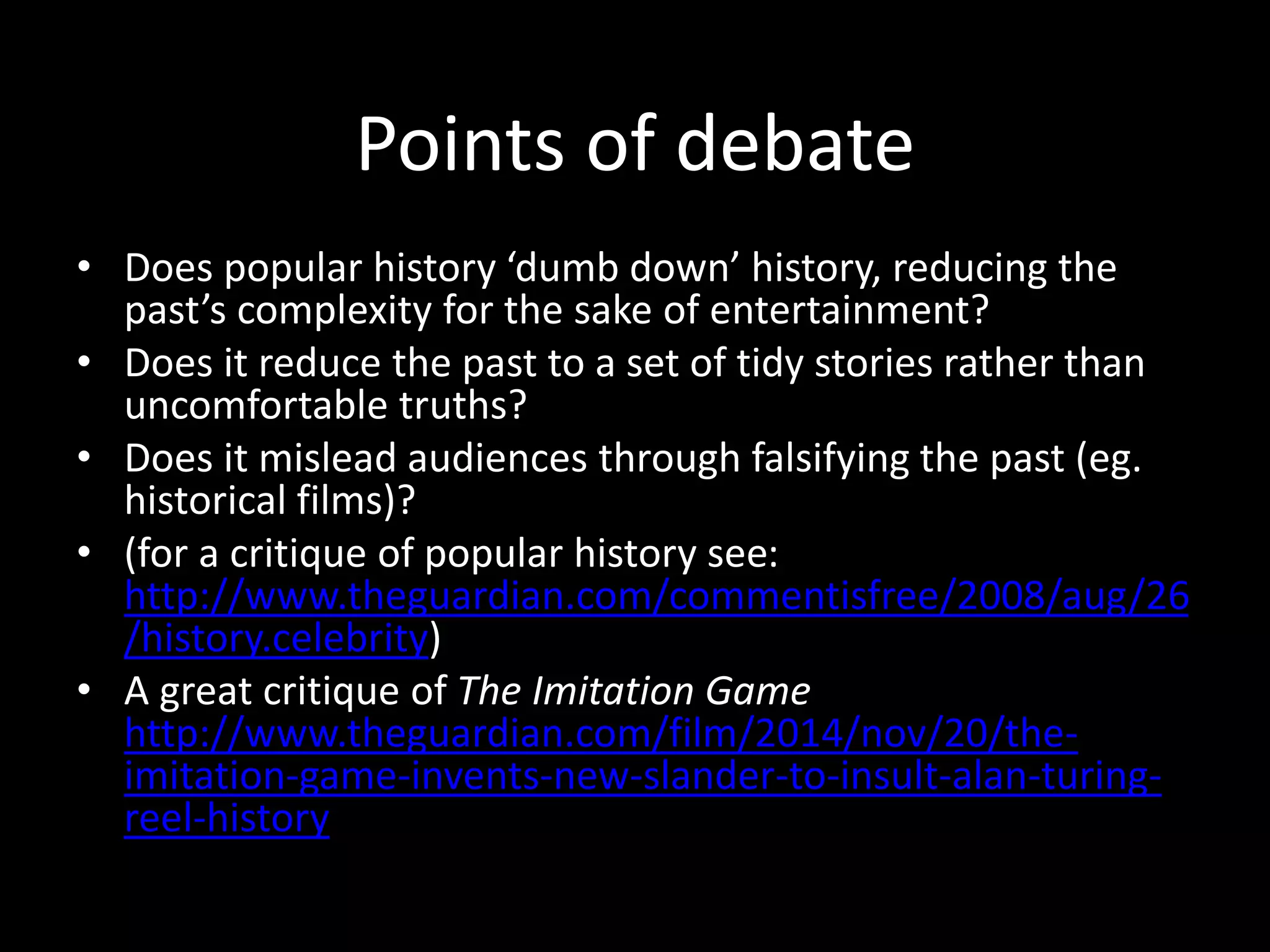

This document discusses the differences between academic, public, and popular history. It defines each field and their intended audiences. Academic historians aim to create new knowledge and publish in peer-reviewed journals, targeting other academics. Public historians interpret history for broader understanding, working with museums and media. Popular historians entertain and tell compelling narratives, targeting general audiences. The fields can overlap and influence each other. Historians must consider audience when selecting topics and communicating research in various forms appropriate to each field.

![• Hilda Kean ‘public history [is] … a practice which has the

capacity for involving people as well as nations and

communities in the creation of their own histories.’

(The Public History Reader, Kean and Martin (eds) 2013)

• ‘Public history not only reflects the history of the

community it seeks to serve, but the very history of that

community will shape the nuances of what is understood as

public history by that community.’ (Dr Robin McLachlan)

http://www.publichistory.org/what_is/definition.html](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/htadaytalkarrow-151204222926-lva1-app6892/75/HTA-day-talk-M-Arrow-9-2048.jpg)

![• ”[Michael Frisch] contends that what differentiates public

history from academic history is its focus on audience."

(Stephen L. Reckon, "Doing Public History: A Look at the How, but Especially

the Why," American Quarterly Volume 45, Issue 1 (March 1993): 188.)

• Public historians work with and for the general public.

• Public history is still underpinned by historical research but

its audience is wider than academic history

• public historians work in museums, galleries, archives

interpretive sites, commemorative plaques, reenactments,

heritage assessments, the media (documentaries etc), and

public policy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/htadaytalkarrow-151204222926-lva1-app6892/75/HTA-day-talk-M-Arrow-10-2048.jpg)

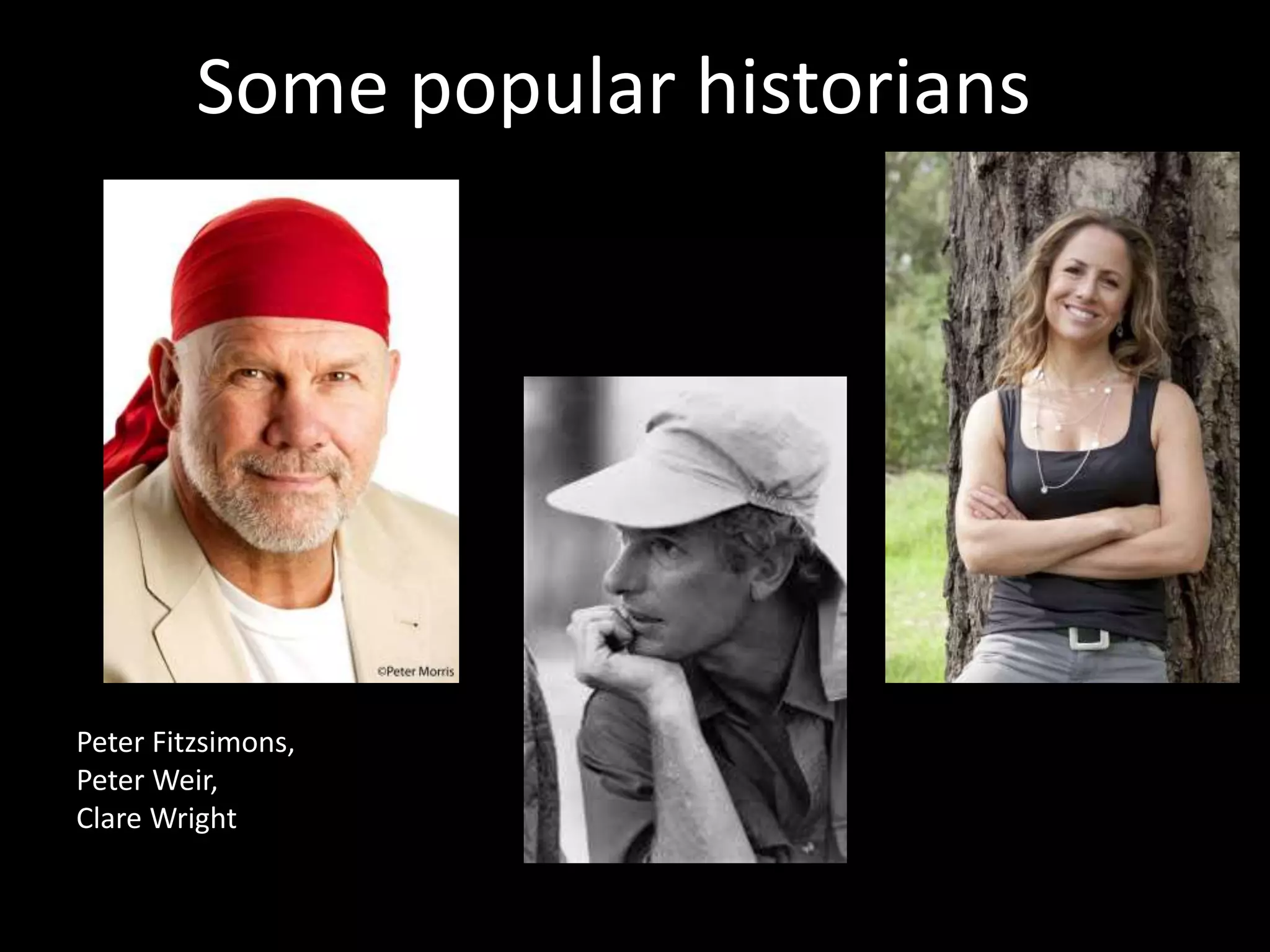

![Academic and Popular Histories

• Popular historians are often subject of scorn and criticism from academics

and vice versa

• Popular histories are usually built on the work of academic historians

• Paul Ham: ‘’Let us not assume, of course, that academic historians want

their work to be read. Many do not. Many seem to harbour an abhorrence

of mass approval. To be popular in certain ivory towers is the kiss of death.

They have little to fear in this regard. The deadening verbosity and

sprawling sentences of the worst examples of academic writing render

them incomprehensible to the mortal reader.[…] most academic historians

presume to judge popular history as if they know best, and almost always

according to their faculty's standards.’

• http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/human-factors-20140320-

353nd.html](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/htadaytalkarrow-151204222926-lva1-app6892/75/HTA-day-talk-M-Arrow-30-2048.jpg)