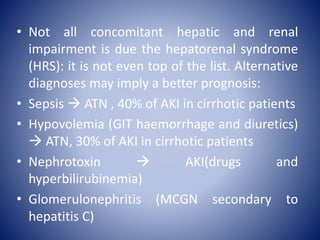

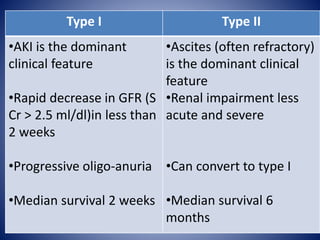

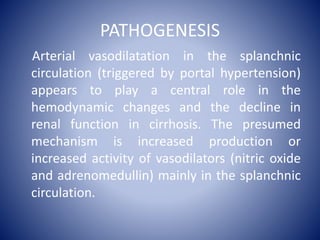

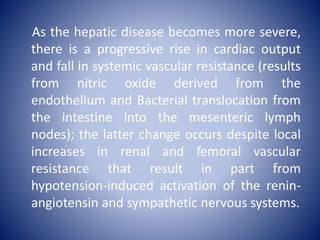

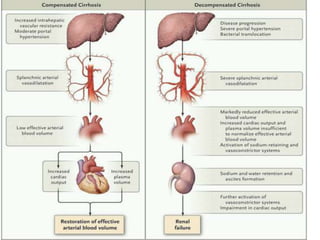

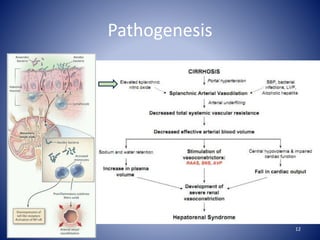

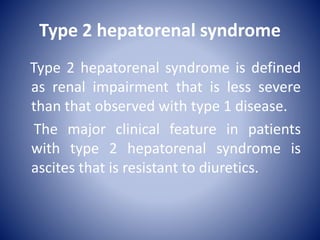

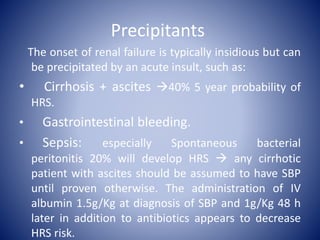

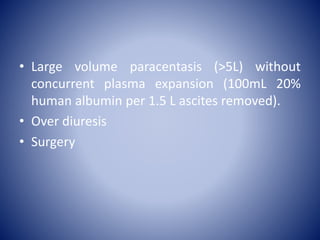

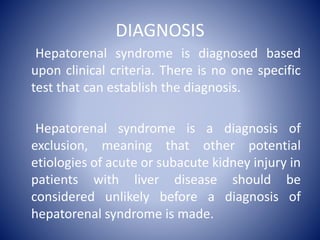

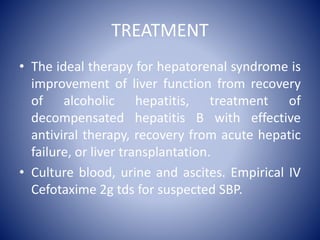

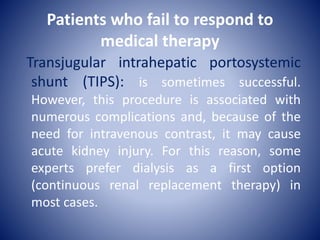

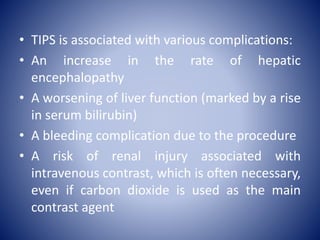

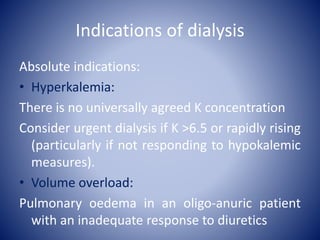

Hepatorenal syndrome is a type of kidney failure seen in patients with cirrhosis or acute liver failure. It occurs due to severe vasodilation in the splanchnic circulation leading to renal hypoperfusion. There are two types - type 1 is characterized by a rapid decline in kidney function over less than 2 weeks, while type 2 is less severe but still associated with refractory ascites. Treatment involves volume expansion with albumin and vasoconstrictors like terlipressin or midodrine to increase renal blood flow. Dialysis or liver transplantation may be needed for patients who do not respond to medical therapy. The prognosis is poor without treatment or liver recovery/transplantation.

![Not critically ill patient:

• Terlipressin in combination with albumin:

Vasopressin analogues: Terlipressin is given as an

intravenous bolus (1 to 2 mg every four to six hours),

act via splanchnic V1 receptors ↓ serum creatinine,

↑ urine output, ↑ MAP and improved early survival.

Side effects: Ischemia cardiac, digital and

mesenteric.

Albumin is given for two days as an intravenous bolus (1

g/kg per day [100 g maximum]), followed by 25 to 50

grams per day until terlipressin therapy is discontinued.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hrspresentation-180629153441/85/Hepatorenal-syndrome-presentation-38-320.jpg)

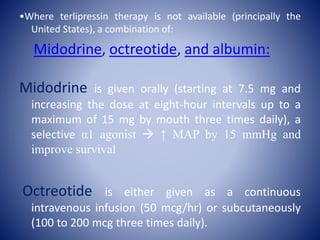

![• Albumin is given for two days as an

intravenous bolus (1 g/kg per day [100 g

maximum]), followed by 25 to 50 grams per

day until midodrine and octreotide therapy is

discontinued.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hrspresentation-180629153441/85/Hepatorenal-syndrome-presentation-40-320.jpg)

![Critically ill patient:

Norepinephrine in combination with

albumin:

• Norepinephrine is given intravenously as a

continuous infusion (0.5 to 3 mg/hr) with the

goal of raising the mean arterial pressure by

10 mmHg

• Albumin is given for at least two days as an

intravenous bolus (1 g/kg per day [100 g

maximum]).

• Intravenous vasopressin may also be

effective, starting at 0.01 units/min and

titrating upward as needed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hrspresentation-180629153441/85/Hepatorenal-syndrome-presentation-41-320.jpg)

![Hepatorenal syndrome regularly

develops in patients with systemic

bacterial infection (eg, spontaneous

bacterial peritonitis [SBP]) and/or severe

alcoholic hepatitis. The following

therapies may prevent the development

of hepatorenal syndrome in these

patients:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hrspresentation-180629153441/85/Hepatorenal-syndrome-presentation-49-320.jpg)