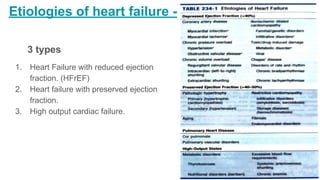

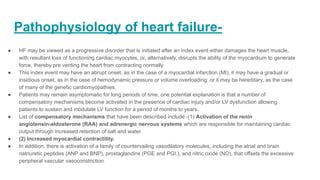

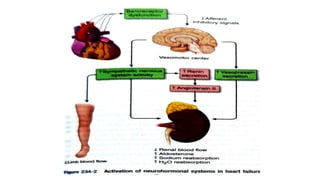

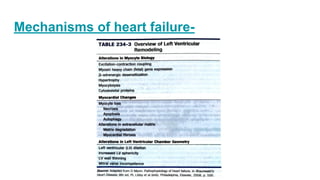

Heart failure is a clinical syndrome where the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the body's needs. It can be caused by structural or functional cardiac abnormalities and results in symptoms like dyspnea and fatigue. There are three main types classified by ejection fraction. The pathophysiology involves an initial damaging event followed by compensatory mechanisms that eventually fail, leading to left ventricular remodeling. Symptoms and signs include fatigue, edema, and elevated jugular venous pressure. Treatment focuses on managing symptoms, preventing disease progression through medications like ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, and ARNi, and treating underlying causes.