This document is the preface for the 18th Edition of Internal Medicine Self-Assessment and Board Review. It discusses the editorial board members and their academic appointments. It also thanks the editors of Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine for their confidence in producing a companion text. The preface expresses the hope that this review book will help students, residents and practitioners learn, read, investigate and question to continue growing in their medical knowledge and care of patients.

![27

SECTION

I

ANSWERS

Pretest probability × Test sensitivity

Posttest probability =

(Pretest probability × Test sensitivity) +

[(1 - Pretest probability) × False-positive rate]

In most occasions, the pretest probability is an estimate based on the prevalence of disease

in the population and the clinical situation. The false-positive rate is 1 - specificity. In this

clinical scenario, the pretest probability of disease was estimated at 10%, and the treadmill

ECG stress test has an average sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 84%. Based on the

formula above, the posttest probability would be low at only 31%.

Posttest probability = (0.10)(0.66)/[(0.10)(0.66) + (0.90)(0.16)] = 0.31

I-8 and I-9. The answers are C and C, respectively. (Chap. 3) In evaluating the usefulness of a

test, it is imperative to understand the clinical implications of the sensitivity and spe-

cificity of that test. Simply, the sensitivity is the proportion of people with disease that

are correctly identified by the test—the true-positive rate. Alternatively, the specificity

can be viewed as the true-negative rate and is the proportion of individuals without

disease who would have a negative test result. The perfect test would have a sensitivity

of 100% and a specificity of 100%, but this is unachievable in clinical practice. Sensitiv-

ity and specificity are inherent properties of the test and are not affected by the disease

prevalence. However, by obtaining information about the prevalence of the disease in

the population, one can generate a two-by-two table, as shown below. This table is used

to generate the total number of patients in each group of the population. The sensitivity

of the test is TP/(TP + FN). The specificity is TN/(TN + FP). In this case, the disease

prevalence is 10%. In a population of 1000 individuals, 100 would truly have latent

tuberculosis, and the table is filled in as follows:

Latent Tuberculosis

+ −

Test + 90 180

− 10 720

I-10. The answer is D. (Chap. 3) A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve plots sensitiv-

ity (or true-positive rate) on the y-axis and 1 − specificity (or false-positive rate) on the

x-axis. Each point on the curve represents a cutoff point of sensitivity and 1 − specificity,

and these cutoff points are used to select the threshold value for a diagnostic test that

yields the best trade-off between true-positive and false-positive tests. The area under the

curve can be used as a quantitative measure of the information content of a test. Values

range from 0.5 (a 45-degree line) representing no diagnostic information to 1.0 for an

ideal test. In the medical literature, ROC curves are often used to compare alternative

diagnostic tests, but the interpretation of a specific test and ROC curve is not as simple

in clinical practice. One criticism of the ROC curve is that it only evaluates only one test

parameter with exclusion of other potentially relevant clinical data. Also, one must con-

sider the underlying population in which the ROC curve was validated and how general-

izable this is the entire population with disease.

I-11. The answer is C. (Chap. 3) The positive and negative predictive values of a test are

strongly influenced by the prevalence of disease in a population. The positive predictive

value is calculated as the number of true-positive test results divided by the number of

all positive test values. Alternatively, the negative predictive value is calculated as the

number of true-negative test results divided by the number of all negative test results.

For example, in a population of 1000 with a disease prevalence of 5%, a specific test has

a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 80%. In this setting, the two-by-two table would

be completed as follows:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/harrisonstudyquestions-220828054547-205e1bc6/85/Harrison-study-questions-pdf-34-320.jpg)

![28

SECTION

I

Introduction

to

Clinical

Medicine

Disease

+ −

Test + 48 190

− 2 760

Thus, the positive predictive value of the test would be [48/(48 + 190)] × 100 = 20.2%, and

the negative predictive value would be [760/(760 + 2)] × 100 = 99.7%.

The sensitivity and specificity of the test, however, are properties of the test and are not

affected by disease prevalence. Positive and negative likelihood ratios are calculated from

the sensitivity and specificity and are defined as the ratio of the probability of a given test

result (positive or negative) in an individual with disease to the probability of that test

result in a patient without disease. For a positive likelihood ratio, a higher ratio indicates

that a test performs better at identifying a patient with disease. For the negative likelihood

ratio, a smaller ratio performs better at ruling out disease. The number needed to treat is a

measure of the effectiveness of an intervention. It is simply calculated as 1 divided by the

absolute reduction in risk related to the intervention.

I-12 and I-13. The answers are B and C, respectively. (Chap. 3) The goal of a meta-analysis is to

summarize the treatment benefit conferred by an intervention by combining and sum-

marizing data available from multiple clinical trials. Meta-analyses often focus on sum-

mary measures of relative risk reductions expressed by the relative risk or odds ratios;

however, clinicians should also understand the absolute risk reduction (ARR) related to

an intervention. This is the difference in mortality (or another endpoint) between the

treatment and the placebo arms. In this case, the absolute risk reduction is 10% − 2% =

8%. From this number, one can calculate the number needed to treat (NNT), which is 1/

ARR. The NNT is the number of patients who must receive the intervention to prevent

one death (or another outcome assessed in the study). In this case, the NNT is 1/8% =

12.5 patients.

I-14. The answer is E. (Chap. 4) Within a population, it is certainly impractical to perform

all possible screening procedures for the variety of diseases that exist in that popula-

tion. This approach would be overwhelming to the medical community and would not

be cost effective. Indeed, the amount of monetary and psychological stress that would

occur from pursuing false-positive test results would add an additional burden on the

population. When determining which procedures should be considered as screening

tests, a variety of endpoints can be used. One of these is to determine how many indi-

viduals would need to be screened in the population to prevent or alter the outcome in

one individual with disease. Although this can be statistically determined, there are no

recommendations for what the threshold value should be and may change based on the

invasiveness or cost of the test and the potential outcome avoided. Additionally, one

should consider both the absolute and relative impact of screening on disease outcome.

Another measure used in considering the utility of screening tests is the cost per life

year saved. Most measures are considered cost effective if they cost less than $30,000 to

$50,000 per year of life saved. This measure is also sometimes adjusted for the quality of

life as well and presented as quality-adjusted life years saved. A final measure that is used

in determining the effectiveness of a screening test is the effect of the screening test on

life expectancy of the entire population. When applying the test across the entire popu-

lation, this number is surprisingly small, and a goal of about 1 month is desirable for a

population-based screening strategy.

I-15. The answer is C. (Chap. 4) Evaluating the utility of screening tests requires also under-

standing the potential biases that can exist when interpreting data from screening tri-

als. One of the most difficult to ascertain but potentially the most confounding is lead

time bias. Simply, lead time bias refers to the bias that occurs when one finds a tumor at

an earlier clinical stage than would be expected from usual care but ultimately does not

lead to an overall change in the outcome. In this case, the apparent difference in time to

diagnosis and death likely represents lead time bias. To fully determine this, one would](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/harrisonstudyquestions-220828054547-205e1bc6/85/Harrison-study-questions-pdf-35-320.jpg)

![58

SECTION

I

Introduction

to

Clinical

Medicine

S. pyogenes infection is needed because antibiotic therapy is recommended to decrease

the small risk of acute rheumatic fever. In addition, treatment with antibiotics within

48 hours of onset of symptoms decreases symptom duration and, importantly, decreases

transmission of streptococcal pharyngitis. In adults, the recommended diagnostic proce-

dure by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Infectious Disease Society

of America is a rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococci only. In children,

however, the recommendation is to perform a throat culture for confirmation if the rapid

screen result is negative to limit spread of disease and minimize potential complications.

Throat culture generally is regarded as the most appropriate diagnostic method but can-

not discriminate between colonization and infection. In addition, it takes 24–48 hours

to get a result. Because most cases of pharyngitis at all ages are viral in origin, empiric

antibiotic therapy is not recommended.

I-101. The answer is D. (Chap. 33) Shortness of breath, or dyspnea, is a common presenting

complaint in primary care. However, dyspnea is a complex symptom and is defined as the

subjective experience of breathing discomfort that includes components of physical as

well as psychosocial factors. A significant body of research has been developed regarding

the language by which a patient describes dyspnea with certain factors being more com-

mon in specific diseases. Individuals with airways diseases (asthma, chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease [COPD]) often describe air hunger, increased work of breathing, and

the sensation of being unable to get a deep breath because of hyperinflation. In addition,

individuals with asthma often complain of a tightness in the chest. Individuals with car-

diac causes of dyspnea also describe chest tightness and air hunger but do not have the

same sensation of being unable to draw a deep breath or have increased work of breathing.

A careful history will also lead to further clues regarding the cause of dyspnea. Nocturnal

dyspnea is seen in congestive heart failure or asthma, and orthopnea is reported in heart

failure, diaphragmatic weakness, and asthma that is triggered by esophageal reflux. When

discussing exertional dyspnea, it is important to assess if the dyspnea is chronic and pro-

gressive or episodic. Whereas episodic dyspnea is more common in myocardial ischemia

and asthma, COPD and interstitial lung diseases present with a persistent dyspnea.

Platypnea is a rare presentation of dyspnea in which a patient is dyspneic in the upright

position and feels improved with lying flat. On physical examination of a patient with

dyspnea, the physician should observe the patient’s ability to speak and the use of acces-

sory muscle or preference of the tripod position. As part of vital signs, a pulsus paradoxus

may be measured with a value of greater than 10 mmHg common in asthma and COPD.

Pulsus paradoxus greater than 10 mmHg may also occur in pericardial tamponade. Lung

examination may demonstrate decreased diaphragmatic excursion, crackles, or wheezes

that allow one to determine the cause of dyspnea. Further workup may include pulmonary

function testing, chest radiography, chest CT, electrocardiography, echocardiography, or

exercise testing, among others, to ascertain the cause of dyspnea.

I-102. The answer is B. (Chap. 34) Chronic cough should not be diagnosed until consistently

present for over 2 months. The duration of cough is a clue to its etiology. Acute cough

(3 weeks) is most commonly due to a respiratory tract infection, aspiration event, or

inhalation of noxious chemicals or smoke. Subacute cough (3–8 weeks duration) is fre-

quently the residuum from a tracheobronchitis, such as in pertussis or “post-viral tussive

syndrome.” Chronic cough (8 weeks) may be caused by a wide variety of cardiopul-

monary diseases, including those of inflammatory, infectious, neoplastic, and cardio-

vascular etiologies. In virtually all instances, evaluation of chronic cough merits a chest

radiograph. The list of diseases that can cause persistent coughing without other symp-

toms and without detectable abnormality on physical examination is long. It includes

serious illnesses such as Hodgkin’s disease in young adults and lung cancer in an older

population. An abnormal chest film leads to evaluation of the radiographic abnormality

to explain the symptom of cough. A normal chest image provides valuable reassurance

to the patient and the patient’s family, who may have imagined the direst explanation for

the cough. Chest PET-CT is often helpful in evaluation of solitary pulmonary nodules or

suspected malignancy. Sinus CT should not be utilized in the initial evaluation of chronic

cough without strong historical or physical examination of sinus disease or infection.

While ACE-inhibitor medications are a common cause of chronic cough, measurement](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/harrisonstudyquestions-220828054547-205e1bc6/85/Harrison-study-questions-pdf-65-320.jpg)

![92

SECTION

II

SECTION

II

Nutrition

with about two-thirds of the total dose given during a 24-hour period added to the PN

formula the next day. In more severe cases, intensive insulin support with a separate

infusion of insulin should be used. If a patient has known insulin-dependent diabetes

mellitus, the dose of insulin required is usually twice the usual outpatient dosage.

II-21. The answer is D. (Chap. 75) Initiating enteral support is important in the critically ill, but

does not come without complications. Tube malposition and aspiration are two of the

most common complications of enteral feeding in the intensive care unit (ICU). Many

patients in the ICU have delayed gastric emptying and also have alterations in mental

status that increase the baseline risk of aspiration. This is further worsened in individuals

who are intubated for mechanical ventilation. The act of suctioning alone induces cough-

ing and gastric regurgitation. Endotracheal tubes are poor barriers to aspiration and may

make aspiration worse by transiting across the vocal cords and epiglottis, two of the nor-

mal preventive mechanisms against aspiration. In the care of the ICU patient, measures

should be taken to minimize the risk of aspiration. A primary measure is to keep the

head of the bed elevated to more than 30°. In patients who are having difficulty tolerating

full enteral nutrition, combining enteral and parenteral nutrition should be considered.

Utilizing nurse-directed algorithms for formula advancement based on gastric residuals

and patient tolerance is also important. Generally, feeding should not be held unless the

residual is greater than 300 mL. Finally, the use of nasojejunal feeding tubes placed post–

ligament of Treitz is a recent strategy to decrease the risk of aspiration. Neither nasogastric

nor nasoduodenal tubes decrease the risk of aspiration.

II-22. The answer is C. (Chap. 77) In 2007-2008, the National Health and Nutrition Examina-

tion Surveys (NHANES) found that 68% of the adult population of the United States was

overweight or obese [body mass index (BMI) 25 kg/m2

]. Understanding the worsening

of obesity in the United States requires understanding both the genetic and environmental

factors that contribute to the development of obesity. It is clear that the rapid increase

in obesity in the this county is far greater than can be attributed to changes in genetics.

However, certain genetic factors certainly increase the risk of obesity. Obesity generally

is inherited in a non-Mendelian pattern similar to that of height. Adopted children have

BMIs more closely related to their biologic parents than their adopted parents. Likewise,

monozygotic twins have BMIs more similar than dizygotic twins. Some of the genes that

are known to play a role in the development of obesity include genes for leptin, proo-

piomelanocortin (POMC), and melanin-concentrating hormone, among others. Leptin

is an important hormone in obesity. Produced by adipocytes, this hormone acts at the

hypothalamus to decrease appetite and increase energy expenditure. In humans, muta-

tions of the ob gene lead to decreased leptin production, and mutations of the db gene

cause leptin resistance. The result of these mutations can be either decreased leptin pro-

duction or resistance to leptin, which causes failure of the brain to recognize satiety. These

mutations are generally associated with severe obesity beginning shortly after birth.

II-23. The answer is A. (Chap. 77) Several syndromes have been recognized as being associated

with the development of obesity. Prader-Willi syndrome falls into a category of syndromes

of obesity associated with mental retardation. Individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome are

of short stature with small hands and feet. They exhibit hyperphagia, obesity, and neu-

rodevelopmental delay in association with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Endocrine

abnormalities or abnormalities of the hypothalamus are also commonly associated with

obesity. Patients with Cushing’s syndrome have central obesity, hypertension, and glucose

intolerance. Hypothyroidism is associated with obesity due to decreases in metabolic rate;

however, it is a rare cause of obesity. Individuals with insulinoma often are obese, as they

increase their caloric intake to try to prevent hypoglycemia episodes. Finally, individuals

with hypothalamic dysfunction due to craniopharyngioma or other disorders lack the

ability to respond to typical hormonal signals that indicate satiety, and therefore develop

obesity. Acromegaly is not associated with obesity.

II-24. The answer is E. (Chap. 78) With over 60% of the U.S. population being overweight or

obese, the primary care physician should be monitoring weight and BMI at every visit and

making recommendations for weight loss to prevent long-term complications of obes-

ity, including hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes mellitus. Despite the very](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/harrisonstudyquestions-220828054547-205e1bc6/85/Harrison-study-questions-pdf-99-320.jpg)

![94

SECTION

II

SECTION

II

Nutrition

obsessional and perfectionist behavior. Patients with AN have an abnormal body image

with an irrational fear of weight gain, despite being underweight. Weight loss is seen as a

fulfilling accomplishment, and individuals with AN will have markedly decreased caloric

intake and also excessive exercise. Despite this, those with AN will not complain of hunger.

Although classically associated with bulimia nervosa, binge eating occurs in 25–50% of

those with AN. As patients with AN become more obsessed with the eating disorder, they

will become more socially isolated with an increased focus on exercise, dieting, and study-

ing. Patients with AN often do not think they have a problem and only seek evaluation

after pressure from family and friends. Amenorrhea is one of the diagnostic criteria. On

physical examination, the patient will generally be underweight for height. Vital signs may

show bradycardia and hypotension. Lanugo hair, acrocyanosis, and edema may be seen.

Salivary gland enlargement may lead to a fullness of the face despite the overall starved

appearance. On laboratory examination, anemia and leukopenia are common. The basic

metabolic panel often demonstrates hyponatremia and hypokalemia with a metabolic

alkalosis. BUN and creatinine may be slightly elevated despite the low muscle mass.

Endocrine abnormalities are very common on laboratory examination and reflect

hypothalamic dysfunction. Thyroid studies show a pattern characteristic of sick euthy-

roid syndrome [low thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), low T4, low T3, and elevated

reverse T3]. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion is very low and asso-

ciated with low levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone

(LH). Given the generally stressed state of the body, however, serum and urine cortisol

may be elevated.

The primary treatment of AN requires intensive psychotherapy under the care of

an experienced psychologist or psychiatrist along with careful medical follow-up. The

goal of treatment is to restore body weight to 90% of predicted body weight or higher.

For patients with significant electrolyte abnormalities or body weight less than 75%

predicted, inpatient treatment is recommended. Nutrition is primarily accomplished

through oral feeding. The initial caloric intake goal is about 1200–1800 kcal/d with

close follow-up to observe for evidence of refeeding syndrome. The weight gain goal is

1–2 kg weekly with advancement of caloric goal to 3000–4000 kcal/d. As many patients

resist weight gain and lie about oral intake, supervised mealtimes are required in both

inpatient and outpatient settings. As part of therapy, individuals must confront issues

with body image. No psychotropic medications have been demonstrated to improve

outcomes in AN. Appetite stimulants also have no role in the treatment of AN. Doxepin

is a tricyclic antidepressant that has mild appetite-stimulating properties; however, it

has not been trialed in AN and has side effects that include prolongation of the QT

interval and should be avoided. The endocrine abnormalities do not have to be treated

either, as these cortisol and thyroid hormone levels will correct with adequate nutrition.

Patients should receive calcium and vitamin D supplementation, but estrogens have no

benefit on bone density in underweight patients. Bisphosphonates can yield improve-

ments in bone density, but the risks of therapy in young individuals are felt to outweigh

the benefits.

II-28. The answer is C. (Chap. 79) Binge-eating disorder has a higher lifetime prevalence than

bulimia nervosa or anorexia nervosa at about 4%. Although more men suffer from binge-

eating disorder than other types of eating disorders, women with binge-eating disorder

still outnumber men 2:1. Binge-eating disorder and bulimia nervosa share the common

characteristic of episodes of eating a large amount of food in a short period of time with

a feeling that the eating behavior is out of control. However, patients with binge-eating

disorder do not exhibit inappropriate behaviors such as self-induced vomiting or the use

of laxatives as a means to control the binge eating. Both binge-eating disorder and bulimia

nervosa are associated with the presence of normal menstrual cycles in women. Individu-

als with binge-eating disorder are more likely to be obese and also have higher rates of

anxiety and depression.

II-29. The answer is E. (Chap. 79) Based on the American Psychiatric Association’s practice

guidelines, inpatient treatment or partial hospitalization is indicated for patients whose

weight is less than 75% of expected for age and height, who have severe metabolic dis-

turbances (e.g., electrolyte disturbances, bradycardia, hypotension), or who have serious](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/harrisonstudyquestions-220828054547-205e1bc6/85/Harrison-study-questions-pdf-101-320.jpg)

![115

section

III

ANSWERS

hemoglobin is made, the cells get larger, not darker. Fragmented red cells, or schistocytes,

are helmet-shaped cells that reflect microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (e.g., thrombotic

thrombocytopenic purpura, disseminated intravascular coagulation, hemolytic uremic

syndrome, scleroderma crisis) or shear damage from a prosthetic heart valve.

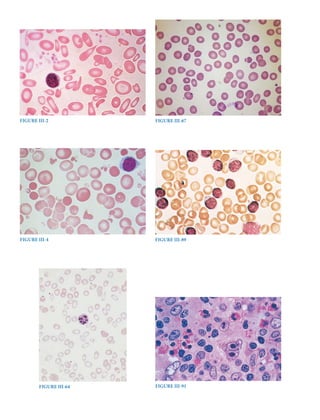

III-2. TheanswerisA.(Chap.57)Thispatientwithanemiademonstratesalowmeancellvolume,

low mean cell hemoglobin, and low mean cell hemoglobin concentration. The peripheral

smear demonstrates microcytic and hypochromic cells, which would be expected given

these laboratory findings. In addition, there is marked variation in size (anisocytosis) and

shape (poikilocytosis). These findings are consistent with severe iron-deficiency anemia,

and serum ferritin would be expected to be less than 10 to 15 μg/L. A low haptoglobin

level would be seen in cases of hemolysis, which can be intravascular or extravascular

in origin. In intravascular hemolysis, the peripheral smear would be expected to show

poikilocytosis with the presence of schistocytes (fragmented red blood cells [RBCs]).

In extravascular hemolysis, the peripheral smear would typically shows spherocytes.

Hemoglobin electrophoresis is used to determine the presence of abnormal hemoglobin

variants. Sickle cell anemia is the most common form and demonstrates sickled RBCs.

Thalassemias are also common inherited hemoglobinopathies. The peripheral smear

in thalassemia often shows target cells. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

deficiency

leads to oxidant-induced hemolysis with presence of bite cells or blister cells. Vitamin B12

deficiency leads to

macrocytosis, which is not consistent with this case.

III-3. The answer is C. (Chap. 57) The reticulocyte index and reticulocyte production index are

useful in the evaluation of anemia to determine the adequacy of bone marrow response to

the anemia. A normal reticulocyte count is 1% to 2%, and in the presence of anemia, this

would be expected to rise to more than two to three times the normal value (the

reticulocyte

index). The reticulocyte index is calculated as Reticulocyte count × (Patient’s hemoglobin/

Normal hemoglobin). In this case, the reticulocyte index would be 5.4%. A

second

correction is further necessary in this patient given the presence of

polychromatophilic

macrocytes on peripheral smear. This finding indicates premature release of reticulocytes

from the bone marrow (“shift cells”), and thus these cells have a longer life span. It is rec-

ommended to further divide the reticulocyte index by a factor of 2, which is known as the

reticulocyte production index. In this case, the value would be 2.7%.

III-4. The answer is C. (Chap. 57) This blood smear shows fragmented red blood cells (RBCs) of

varying size and shape. In the presence of a foreign body within the circulation

(prosthetic

heart valve, vascular graft), RBCs can become destroyed. Such intravascular hemoly-

sis will also cause serum lactate dehydrogenase to be elevated and hemoglobinuria. In

isolated extravascular hemolysis, there is no hemoglobin or hemosiderin released into

the urine. The characteristic peripheral blood smear in splenomegaly is the presence of

Howell-Jolly bodies (nuclear remnants within red blood cells). Certain diseases are asso-

ciated with extramedullary hematopoiesis (e.g., chronic hemolytic anemias), which can

be detected by an enlarged spleen, thickened calvarium, myelofibrosis, or hepatomegaly.

The peripheral blood smear may show teardrop cells or nucleated RBCs. Hypothyroidism

is associated with macrocytosis, which is not demonstrated here. Chronic gastrointestinal

blood loss will cause microcytosis, not schistocytes.

III-5. The answer is A. (Chap. 81) Although cigarette smoking is the greatest modifiable risk

factor for the development of cancer, the most significant risk factor for cancer in general

is age. Two-thirds of all cancers are diagnosed in individuals older than 65 years, and the

risk of developing cancer between the ages of 60 and 79 years is one in three in men and

one in five in women. In contrast, the risk of cancer between birth and age 49 years is one

in 70 for boys and men and one in 48 for girls and women. Overall, men have a slightly

greater risk of developing cancer than women (44% vs. 38% lifetime risk).

III-6. The answer is A. (Chap. 81) The cause of cancer death differs across the life span. In

women who are younger than 20 years of age, the largest cause of cancer death is leuke-

mia. Between the ages of 20 and 59 years, breast cancer becomes the leading cause of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/harrisonstudyquestions-220828054547-205e1bc6/85/Harrison-study-questions-pdf-122-320.jpg)

![138

section

III

Oncology

and

Hematology

Survival rates of 50% at 3 years have been reported, but older patients are particularly

prone to develop treatment-related mortality and morbidity. Results of transplant using

matched unrelated donors are comparable, although most series contain younger and

more highly selected cases. However, multiple new drugs have been approved for use in

MDS. Several regimens appear to not only improve blood counts but also to delay onset

of leukemia and to improve survival.

Lenalidomide, a thalidomide derivative with a more favorable toxicity profile, is

particularly effective in reversing anemia in MDS patients with 5q- syndrome; a high

proportion of these patients become transfusion independent.

III-75. The answer is E. (Chap. 108) The World Health Organization’s classification of the chronic

myeloproliferative diseases (MPDs) includes eight disorders, some of which are rare or

poorly characterized but all of which share an origin in a multipotent hematopoietic pro-

genitor cell, overproduction of one or more of the formed elements of the blood without

significant dysplasia, a predilection to extramedullary hematopoiesis or myelofibrosis,

and transformation at varying rates to acute leukemia. Within this broad classification,

however, significant phenotypic heterogeneity exists. Some diseases such as chronic

myelogenous leukemia (CML), chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL), and chronic eosi-

nophilic leukemia (CEL) express primarily a myeloid phenotype, but in others, such as

polycythemia vera (PV), primary myelofibrosis (PMF), and essential thrombocytosis

(ET), erythroid or megakaryocytic hyperplasia predominates. The latter three disorders,

in contrast to the former three, also appear capable of transforming into each other. Such

phenotypic heterogeneity has a genetic basis. CML is the consequence of the balanced

translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 [t(9;22)(q34;11)], CNL has been associated

with a t(15;19) translocation, and CEL occurs with a deletion or balanced translocations

involving the PDGFR-alpha gene. By contrast, to a greater or lesser extent, PV, PMF, and

ET are characterized by expression of a JAK2 mutation, V617F, that causes constitutive

activation of this tyrosine kinase that is essential for the function of the erythropoietin

and thrombopoietin receptors but not the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor recep-

tor. This essential distinction is also reflected in the natural history of CML, CNL, and

CEL, which is usually measured in years, and their high rate of transformation into acute

leukemia. By contrast, the natural history of PV, PMF, and ET is usually measured in

decades, and transformation to acute leukemia is uncommon in the absence of exposure

to mutagenic agents. Primary effusion lymphoma is not a myeloproliferative disease. It is

one of the diseases (Kaposi’s sarcoma, multicentric Castleman’s disease) associated with

infection with human herpes virus-8, particularly in immunocompromised hosts.

III-76. The answer is A. (Chap. 108) Polycythemia vera (PV) is a clonal disorder that involves a

multipotent hematopoietic progenitor cell. Clinically, it is characterized by a proliferation

of red blood cells (RBCs), granulocytes, and platelets. The precise etiology is unknown.

Unlike chronic myelogenous leukemia, no consistent cytogenetic abnormality has been

associated with the disorder. However, a mutation in the autoinhibitory, pseudokinase

domain of the tyrosine kinase JAK2—that replaces valine with phenylalanine (V617F),

causing constitutive activation of the kinase—appears to have a central role in the patho-

genesis of PV. Erythropoiesis is regulated by the hormone erythropoietin. Hypoxia is

the physiologic stimulus that increases the number of cells that produce erythropoietin.

Erythropoietin may be elevated in patients with hormone-secreting tumors. Levels are

usually “normal” in patients with hypoxic erythrocytosis. In PV, however, because eryth-

rocytosis occurs independently of erythropoietin, levels of the hormone are usually low.

Therefore, an elevated level is not consistent with the diagnosis. PV is a chronic, indolent

disease with a low rate of transformation to acute leukemia, especially in the absence of

treatment with radiation or hydroxyurea. Thrombotic complications are the main risk for

PV and correlate with the erythrocytosis. Thrombocytosis, although sometimes promi-

nent, does not correlate with the risk of thrombotic complications. Salicylates are useful

in treating erythromelalgia but are not indicated in asymptomatic patients. There is no

evidence that thrombotic risk is significantly lowered with their use in patients whose

hematocrits are appropriately controlled with phlebotomy. Phlebotomy is the mainstay

of treatment. Induction of a state of iron deficiency is critical to prevent a reexpansion of

the RBC mass. Chemotherapeutics and other agents are useful in cases of symptomatic](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/harrisonstudyquestions-220828054547-205e1bc6/85/Harrison-study-questions-pdf-145-320.jpg)

![144

section

III

Oncology

and

Hematology

chemotherapy with cladribine with clinical complete remissions in the majority of patients

and frequent long-term disease-free survival.

III-90. The answer is E. (Chap. 110) Classical Hodgkin’s disease carries a better prognosis than

all types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Patients with good prognostic factors can achieve

cure with extended field radiation alone, but those with a higher risk disease often achieve

cure with high-dose chemotherapy and sometimes radiation. The chance of cure is so

high (90%) that many protocols are now considering long-term sequelae of current ther-

apy such as carcinomas, hypothyroidism, premature coronary disease, and constrictive

pericarditis in those receiving radiation therapy. A variety of chemotherapy regimens are

effective with long-term disease-free survival in patients with advanced disease achieved

in more than 75% of patients who lack systemic symptoms and in 60% to 70% of patients

with systemic symptoms.

III-91. The answer is D. (Chap. 110) The large cell with a bilobed nucleus and prominent nucleoli

giving an “owl’s eyes” appearance near the center of the field is a Reed-Sternberg cell, con-

firming the diagnosis of Hodgkin’s disease. Hodgkin’s disease occurs in 8000 patients in

the United States each year, and the disease does not appear to be increasing in frequency.

Most patients present with palpable lymphadenopathy that is nontender; in most patients,

these lymph nodes are in the neck, supraclavicular area, and axilla. More than half the

patients have mediastinal adenopathy at diagnosis, and this is sometimes the initial mani-

festation. Subdiaphragmatic presentation of Hodgkin’s disease is unusual and more com-

mon in older men. One-third of patients present with fevers, night sweats, or weight loss,

which are B symptoms in the Ann Arbor staging classification. Occasionally, Hodgkin’s

disease can present as a fever of unknown origin. This is more common in older patients

who are found to have mixed cellularity Hodgkin’s disease in an abdominal site. Rarely,

the fevers persist for days to weeks followed by afebrile intervals and then recurrence of

the fever (Pel-Ebstein fever). The differential diagnosis of a lymph node biopsy suspicious

for Hodgkin’s disease includes inflammatory processes, mononucleosis, non-Hodgkin’s

lymphoma, phenytoin-induced adenopathy, and nonlymphomatous malignancies.

III-92. The answer is E. (Chap. e20) A “dry tap” is defined as the inability to aspirate bone marrow

and is reported in approximately 5% of attempts. It is rare in the case of normal bone mar-

row. The differential diagnosis includes metastatic carcinoma infiltration (17%); chronic

myeloid leukemia (15%); myelofibrosis (14%); hairy cell leukemia (10%); acute leukemia

(10%); and lymphomas, including Hodgkin’s disease (9%).

III-93. The answer is B. (Chap. e20) The diagnostic criteria for chronic eosinophilic leukemia

and the hypereosinophilic syndrome first requires the presence of persistent eosinophilia

greater than 1500/μL in blood, increased marrow eosinophils, and less than 20% myelob-

lasts in blood or marrow. Additional disorders that must be excluded include all causes

of reactive eosinophilia, primary neoplasms associated with eosinophilia (e.g., T-cell

lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease, acute lymphoid leukemia, mastocytosis, chronic myelog-

enous leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia [AML], myelodysplasia, and myeloproliferative

syndromes), and T-cell reaction with increased interleukin-5 or cytokine production. If

these entities have been excluded and the myeloid cells show a clonal chromosome abnor-

mality and blast cells (2%) are present in peripheral blood or are increased in marrow

(but 20%), then the diagnosis is chronic eosinophilic leukemia. Patients with hypereosi-

nophilic syndrome and chronic eosinophilic leukemia may be asymptomatic (discovered

on routine testing) or present with systemic findings such as fever, shortness of breath,

new neurologic findings, or rheumatologic findings. The heart, lungs, and central nervous

system are most often affected by eosinophil-mediated tissue damage.

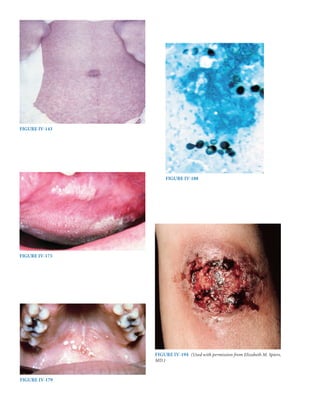

III-94. The answer is D. (Chap. e21) Mastocytosis is a proliferation and accumulation of mast

cells in one or more organ systems. Only the skin is involved in approximately 80% of cases

with the other 20% being defined as systemic mastocytosis caused by the involvement of

another organ system. The most common manifestation of mastocytosis is cutaneous urti-

caria pigmentosa, a maculopapular pigmented rash involving the papillary

dermis. Other](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/harrisonstudyquestions-220828054547-205e1bc6/85/Harrison-study-questions-pdf-151-320.jpg)

![224

SECTION

IV

Infectious

Diseases

of active pulmonary tuberculosis. Skin testing with a purified protein derivative of the

tuberculosis mycobacterium is used to detect latent infection with tuberculosis and has

no role in determining whether active disease is present. The cavitary lung lesion shown

on the chest imaging could represent malignancy or a bacterial lung abscess, but because

the patient is from a high-risk area for tuberculosis, tuberculosis would be considered the

most likely diagnosis until ruled out by sputum testing.

IV-116. The answer is A. (Chap. 165) Initial treatment of active tuberculosis associated with HIV

disease does not differ from that of a non-HIV-infected person. The standard treatment

regimen includes four drugs: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (RIPE).

These drugs are given for a total of 2 months in combination with pyridoxine (vitamin

B6) to prevent neurotoxicity from isoniazid. After the initial 2 months, patients continue

on isoniazid and rifampin to complete a total of 6 months of therapy. These recommen-

dations are the same as those of non–HIV-infected individuals. If the sputum culture

remains positive for tuberculosis after 2 months, the total course of antimycobacterial

therapy is increased from 6 to 9 months. If an individual is already on antiretroviral

therapy (ART) at the time of diagnosis of tuberculosis, it may be continued, but often

rifabutin is substituted for rifampin because of drug interactions between rifampin and

protease inhibitors. In individuals not on ART at the time of diagnosis of tuberculosis, it

is not recommended to start ART concurrently because of the risk of immune reconstitu-

tion inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) and an increased risk of medication side effects. IRIS

occurs as the immune system improves with ART and causes an intense inflammatory

reaction directed against the infecting organism(s). There have been fatal cases of IRIS

in association with tuberculosis and initiation of ART. In addition, both ART and antitu-

berculosis drugs have many side effects. It can be difficult for a clinician to decide which

medication is the cause of the side effects and may lead unnecessarily to alterations in

the antituberculosis regimen. ART should be initiated as soon as possible and prefer-

ably within 2 months. Three-drug regimens are associated with a higher relapse rate if

used as a standard 6-month course of therapy and, if used, require a total of 9 months

of therapy. Situations in which

three-drug therapy may be used are pregnancy, intolerance

to a specific drug, and in the setting of resistance. A five-drug regimen using Rifampin,

isoniazide, pyrazinamide, ethambutol (RIPE) plus streptomycin is recommended as the

standard retreatment regimen. Streptomycin and pyrazinamide are discontinued after

2 months if susceptibility testing is unavailable. If susceptibility testing is available, the

treatment should be based on the susceptibility pattern. In no instance is it appropriate

to withhold treatment in the setting of active tuberculosis to await susceptibility testing.

IV-117. The answer is B. (Chap. 165) The aim of treatment of latent tuberculosis is to prevent

development of active disease, and the tuberculin skin test (purified protein derivative

[PPD]) is the most common means of identifying cases of latent tuberculosis in high-

risk groups. To perform a tuberculin skin test, 5 tuberculin units of PPD are placed

subcutaneously in the forearm. The degree of induration is determined after 48 to 72

hours. Erythema only does not count as a positive reaction to the PPD. The size of the

reaction to the tuberculin skin test determines whether individuals should receive treat-

ment for latent tuberculosis. In general, individuals in low-risk groups should not be

tested. However, if tested, a reaction larger than 15 mm is required to be considered as

positive. School teachers are considered low-risk individuals. Thus, the reaction of 7 mm

is not a positive result, and treatment is not required. A size of 10 mm or larger is consid-

ered positive in individuals who have been infected within 2 years or those with high-risk

medical conditions. The individual working in an area where tuberculosis is endemic has

tested newly positive by skin testing and should be treated as a newly infected individual.

High-risk medical conditions for which treatment of latent tuberculosis is recommended

include diabetes mellitus, injection drug use, end-stage renal disease, rapid weight loss,

and hematologic disorders. PPD reactions 5 mm or larger are considered positive for

latent tuberculosis in individuals with fibrotic lesions on chest radiographs, those with

close contact with an infected person, and those with HIV or who are otherwise immu-

nosuppressed. There are two situations in which treatment for latent tuberculosis is rec-

ommended regardless of the results on skin testing. First, infants and children who have

had close contact with an actively infected person should be treated. After 2 months of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/harrisonstudyquestions-220828054547-205e1bc6/85/Harrison-study-questions-pdf-231-320.jpg)