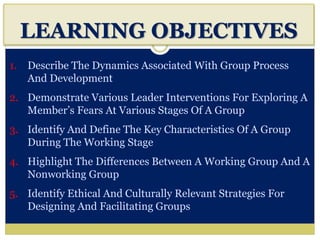

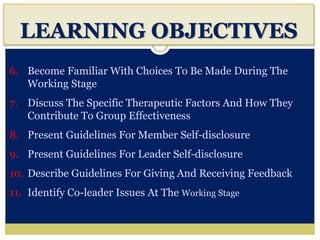

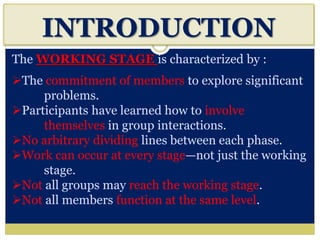

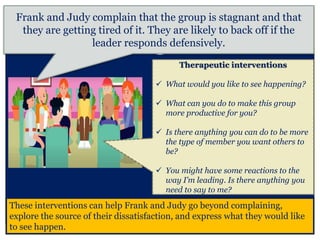

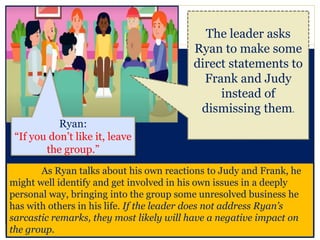

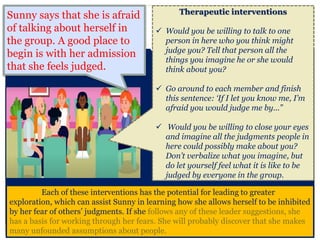

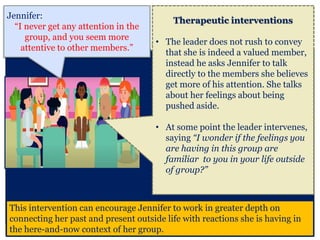

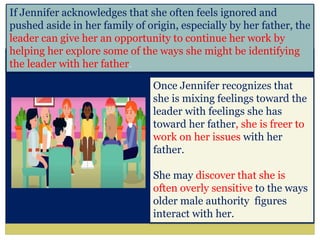

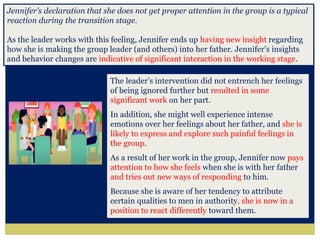

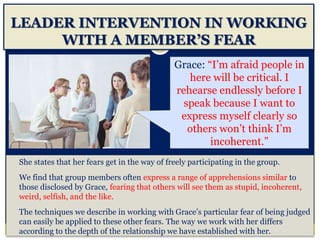

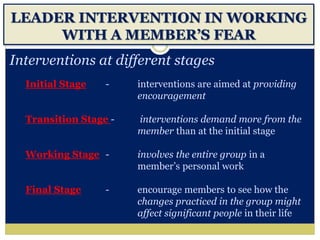

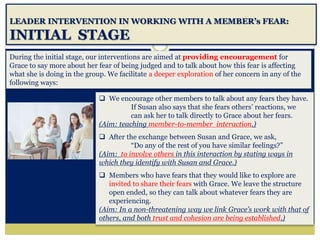

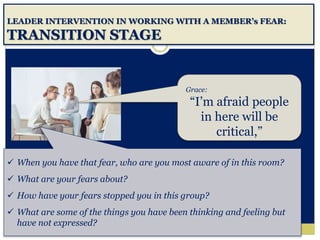

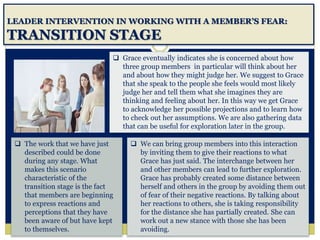

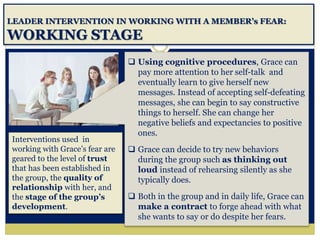

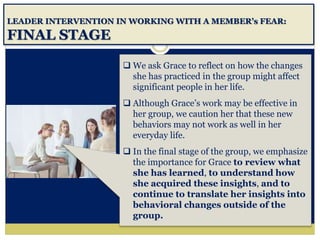

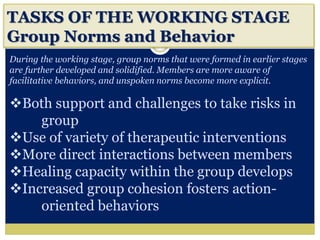

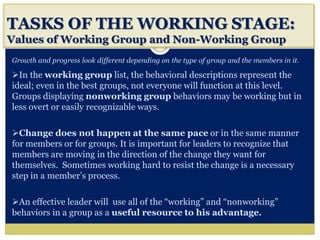

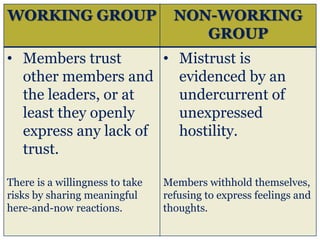

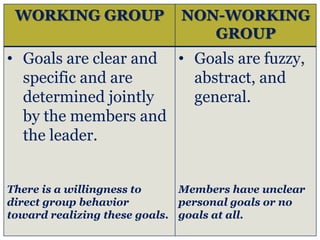

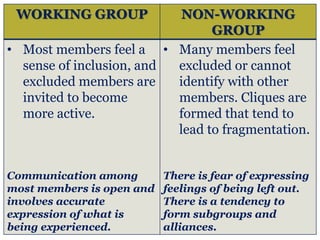

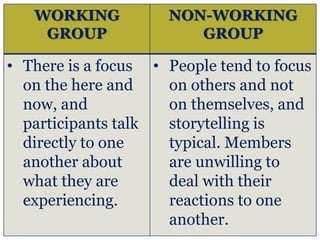

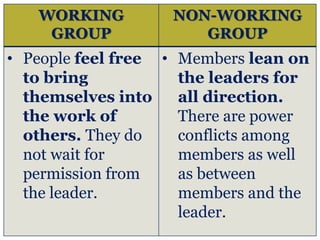

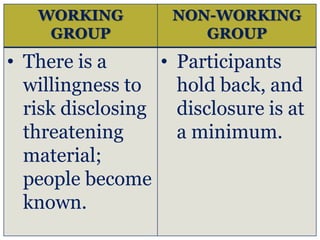

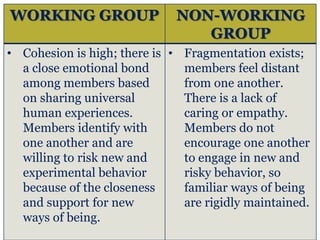

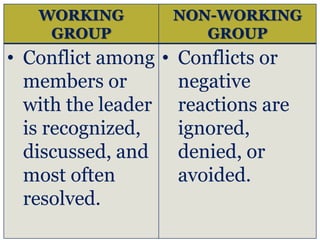

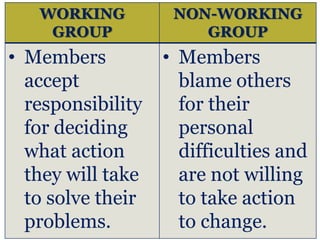

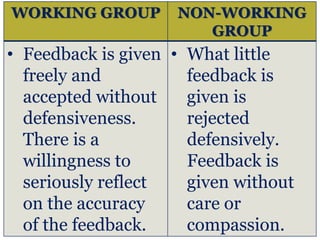

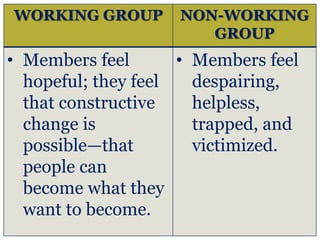

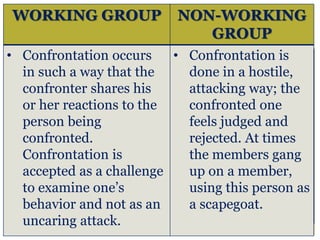

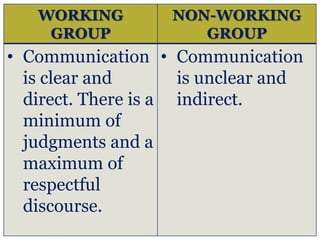

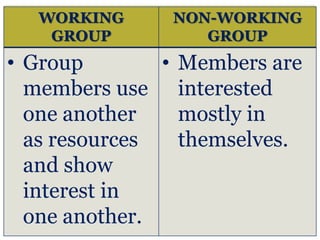

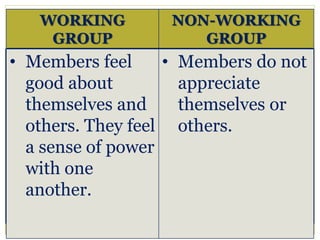

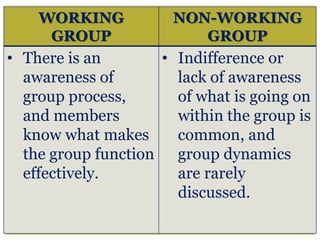

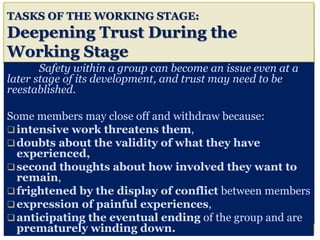

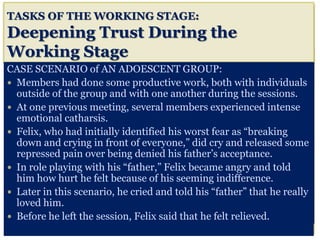

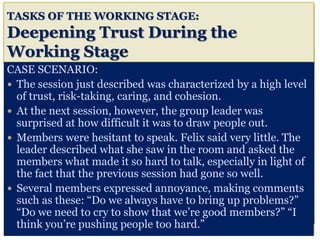

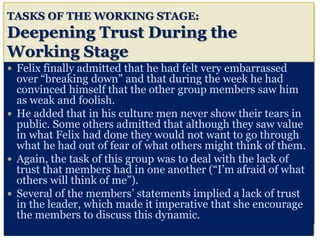

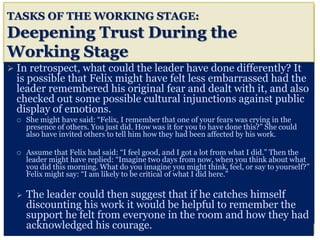

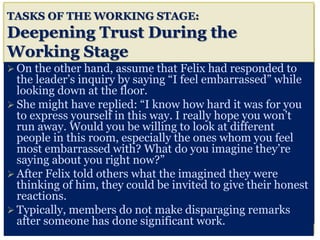

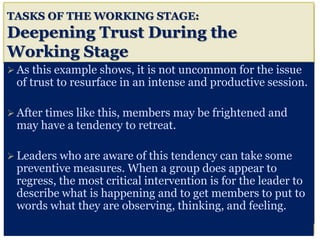

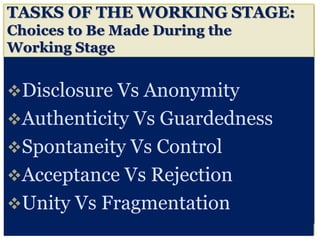

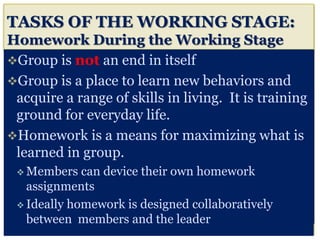

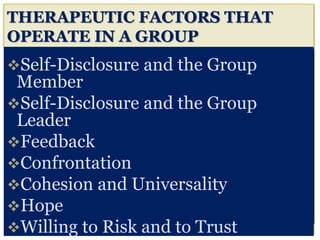

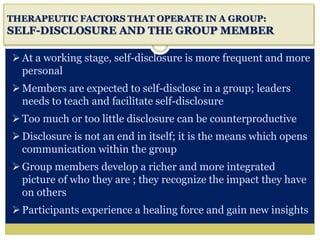

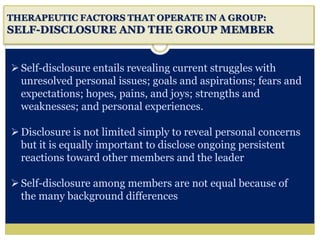

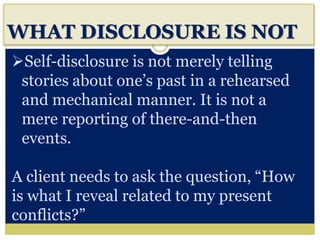

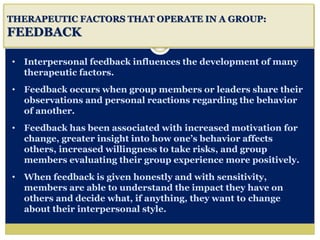

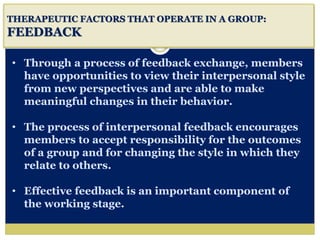

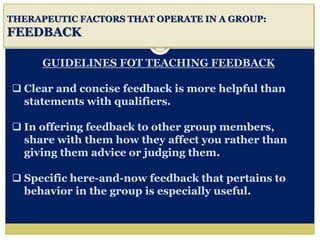

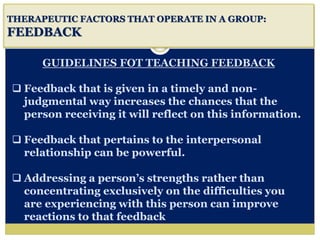

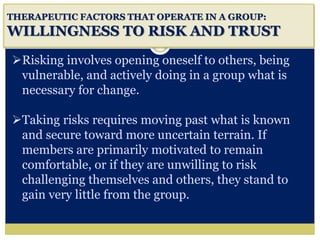

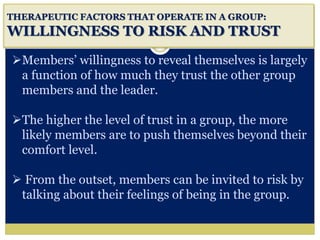

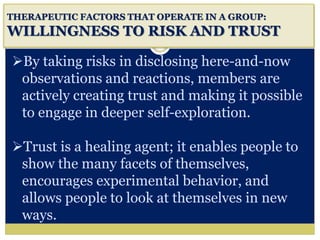

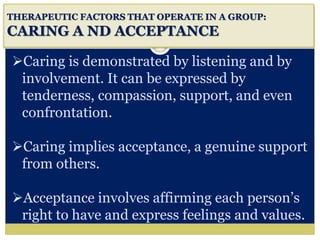

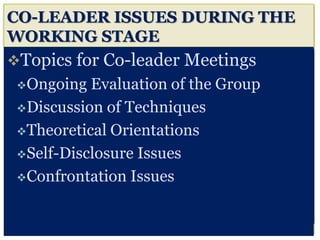

The document describes the working stage of a group. Key characteristics of this stage include members making a deeper commitment to exploring significant problems and learning how to actively participate in group interactions. Effective leader interventions aim to facilitate meaningful exploration of members' personal issues and encourage direct engagement between members. The goals are to help members build trust, strengthen cohesion, and support each other in working through barriers that inhibit the group's progress.