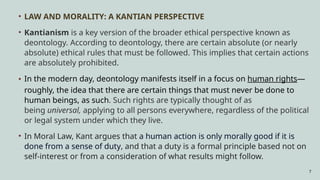

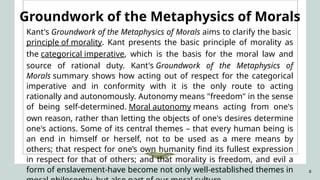

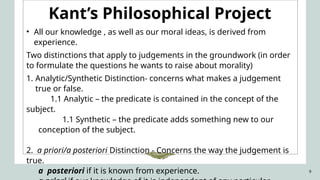

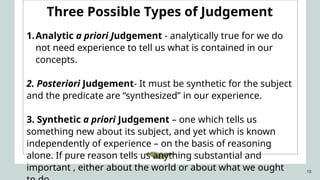

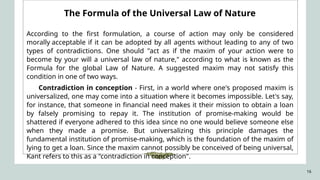

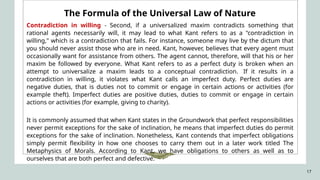

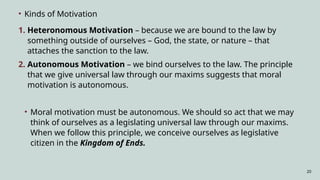

The document presents an overview of Immanuel Kant's moral philosophy, focusing on his deontological approach and the concept of the categorical imperative, which serves as the foundation for his moral law. It emphasizes the importance of treating individuals as ends in themselves and the necessity of acting according to universal principles derived from reason. Kant's framework underscores the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties, asserting that true morality arises from autonomous action based on rationality rather than external influences.