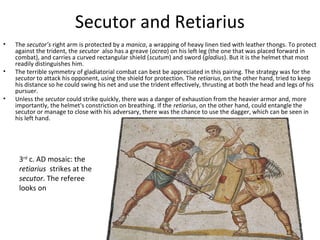

Roman spectacles included theater, chariot racing, and gladiatorial games. Theater days were social events that also included religious ceremonies. The wealthy had the best seats. Chariot racing occurred at the Circus Maximus, which seated over 150,000 spectators. Races lasted about 15 minutes. Gladiatorial combats were held in amphitheaters like the Colosseum and featured fights between men and beasts. Gladiators included trained fighters like the murmillo and retiarius who fought with specific weapons and armor. The games were very popular but also faced criticism for their brutality.