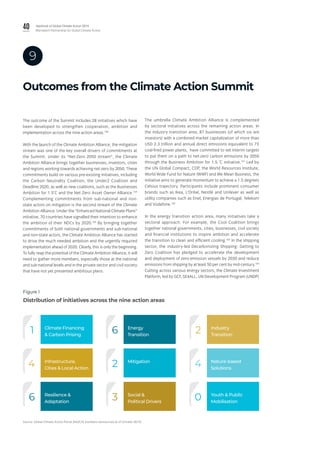

This document provides an executive summary of the 2019 Yearbook of Global Climate Action. It highlights examples of climate action being taken by cities, businesses, and civil society organizations. It finds that international cooperative initiatives aimed at climate action are achieving higher levels of output and performance over time. Momentum for climate action was built in 2019 through regional climate weeks and the UN Climate Action Summit. Key messages are that continued support is needed for implementing climate actions, enhancing collaboration, and increasing climate ambition from all actors. The summary emphasizes the urgent need to close global emissions gaps to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

![v

Acknowledgements

This third edition of the Global Climate Action Yearbook was

made possible by contributions from many organizations and

individuals. Special thanks go to the Marrakech Partnership

Thematic Areas who provided insights in to the state of play of

each of their respective areas as well as case stories.

Special thanks to the team who helped prepare the analysis

in Chapter V. The analysis was jointly led by Dr. Sander

Chan (German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für

Entwicklungspolitik [DIE]; Copernicus Institute of Sustainable

Development at Utrecht University); Dr. Thomas Hale (Blavatnik

School of Government [BSG] at the University of Oxford). Team

members who contributed to the data collection included Malin

Gütschow (DIE), Miriam Lia Cangussu Tomaz Garcia (DIE), Jung

Kian Ng (BSG), Andrew Miner (BSG), Benedetta Nimshani Khawe

Thanthrige (DIE), Sara Posa (DIE), Eugene Tingwey (DIE), James

Tops (DIE). The Analysis was supported by the ClimateSouth

Project (a collaboration between Blavatnik School of Government

at the University of Oxford, the German Development Institute/

Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik [DIE], The Energy

and Resources Institute [TERI], and the African Centre for

Technology Studies [ACTS]) also made contributions. Data on

output performance of cooperative initiatives was collected with

assistance from the German Development Institute/Deutsches

IRENA's 2016 photo competition: Doran Talmi / Location: Bjørnfjell, Narvik, Norway.

Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE)’s “Klimalog” project,

generously funded by the German Federal Ministry of Economic

Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

The High-Level Champions would also like to thank the UNFCCC

secretariat for their steady support throughout the process of

developing the Yearbook.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gcayearbook2019-191127052041/85/Global-Climate-Action-COP25-Madrid-Dec-2019-7-320.jpg)