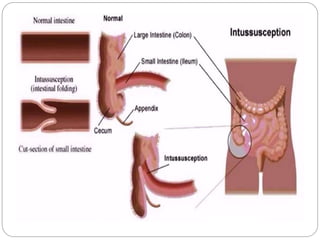

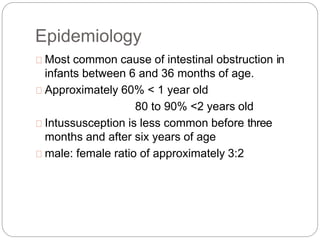

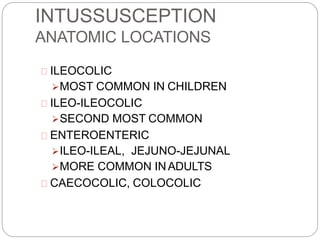

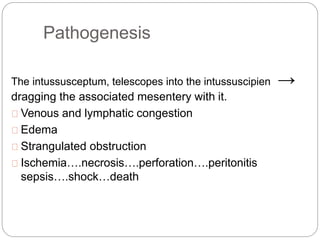

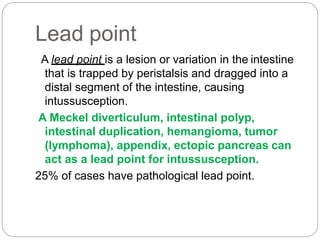

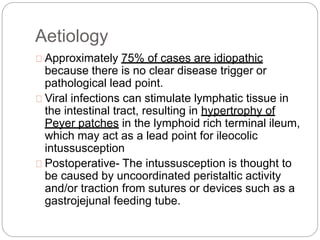

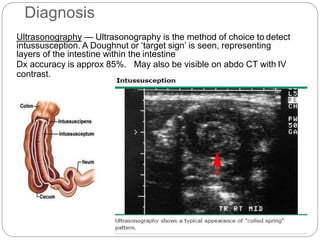

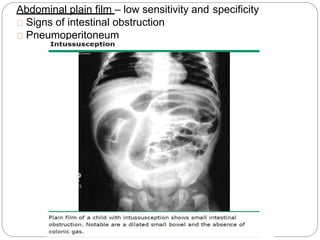

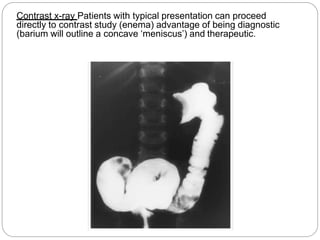

Intussusception is the telescoping of the proximal bowel into the distal bowel. It is most common in children under 2 years old, with the majority of cases being idiopathic. The classic triad of symptoms includes intermittent abdominal pain, a sausage-shaped abdominal mass, and bloody stools, though this triad is present in less than 15% of cases. Ultrasound is the preferred diagnostic tool, showing a target or doughnut-shaped mass. Treatment involves rehydration and stabilization, with non-operative reduction via hydrostatic or pneumatic enema being first-line for stable patients without evidence of perforation. Surgery is pursued if non-operative reduction fails or if there are signs of