This chapter provides an introduction to the third edition of the textbook Fundamentals of Geomorphology. The author summarizes the key changes made to the book's structure based on feedback from reviewers of the second edition. These include splitting the first chapter into three sections introducing different aspects of geomorphology, rearranging material on processes and history throughout the book, and moving the chapter on karst landscapes later in the text. The author expresses his aim to integrate both process geomorphology and historical geomorphology in the book. He also thanks those who assisted with the production of the new edition.

![The idea that increased weathering rates

associated with tectonic uplift increases erosion

and removes enough carbon dioxide from the

atmosphere to control climate has its dissenters.

Ollier (2004a) identified what he termed ‘three

misconceptions’ in the relationships between

erosion, weathering, and carbon dioxide. First,

weathering and erosion are not necessarily cur-

rent processes – erosion, especially erosion in

mountainous regions, may occur with little

chemical alteration of rock or mineral fragments.

Second, in most situations, hydrolysis and not

carbonation is the chief weathering process –

weathering produces clays and not carbonates.

Furthermore, evidence suggests that chemical

weathering rates have declined since the mid- or

early Tertiary, before which time deep weathering

profiles formed in broad plains. Today, deep

weathering profiles form only in the humid

tropics. Third, Ollier questions the accepted

chronology of mountain building, which sees

Tibet, the highlands of western North America,

and the Andes beginning to rise about 40 million

years ago, favouring instead rise over the last few

million years.

HUMANS AS GEOMORPHIC

AGENTS

Geomorphic footprint

Over the last two centuries or so, humans have had

an increasingly significant impact on the transfer

of Earth materials and the modification of

landforms, chiefly through agricultural practices,

mining and quarrying, and the building of roads

and cities. As Harrison Brown (1956, 1031)

commented:

A population of 30 billion would consume rock

at a rate of about 1,500 tons per year. If we were

to assume that all the land areas of the world

were available for such processing, then, on

the average, man [sic] would “eat” his way

downward at a rate of 3.3 millimeters per year,

or over 3 meters per millennium. This figure

gives us some idea of the denudation rates that

might be approached in the centuries ahead.

And it gives us an idea of the powers for

denudation which lie in mankind’s hands.

The ‘geomorphic footprint’ is a measure of the

rate at which humans create new landforms and

mobilize sediment (Rivas et al. 2006). For four

study areas – one in northern Spain and three in

central and eastern Argentina – new landforms

were created by excavation and mining activities

at a rate of 7.9 m2

per person per year in the

Spanish area and 5.93 m2

per person per year in

the Argentinean areas. The volume of sediment

created by these activities was 30.4 m3

per person

per year and 6.4 m3

per person per year for the

Spanish and Argentinean areas respectively. These

values convert to a sediment mobilization rate of

2.4 mm/yr for the Spanish study site and 0.8

mm/yr for the Argentinian study sites, which

values exceed the rate mobilization of sediment by

natural processes by an order of magnitude of

two. If these figures are typical of other human-

dominated areas, then Brown’s denudation rates

may be reached during the present century with

a smaller population.

Humans have become increasingly adept at

ploughing land and at excavating and moving

materials in construction and mining activities.

Indeed, humans are so efficient at unintentionally

and deliberately moving soils and sediments that

they have become the leading geomorphic agent

of erosion (e.g. Hooke 2000). Placing human-

induced erosion in a geological perspective

demonstrates the point (Wilkinson 2005). The

weathered debris stored in continental and oceanic

sedimentary rocks suggest that, on average,

continental surfaces have lowered through natural

denudation at a rate of a few tens of metres per

million years. By contrast, construction, mining,

and agricultural activities presently transport

sediment and rock, and lower all ice-free

continental surfaces by a few hundred metres per

million years. Therefore, the human species is

80 INTRODUCING LANDFORMS AND LANDSCAPES](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofgeomorphologyroutledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-220921044803-9a19de6c/85/fundamentalsofgeomorphology_routledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-pdf-97-320.jpg)

![WEATHERING AND ASSOCIATED LANDFORMS 143

pH is a measure of the acidity or alkalinity of aqueous solutions. The term stands for the

concentration of hydrogen ions in a solution, with the p standing for Potenz (the German

word for ‘power’). It is expressed as a logarithmic scale of numbers ranging from about 0 to 14

(Figure 7.2). Formulaically, pH = –log[H+

], where [H+

] is the hydrogen ion concentration (in gram-

equivalents per litre) in an aqueous solution. A pH of 14 corresponds to a hydrogen ion con-

centration of 10–14

gram-equivalents per

litre. A pH of 7, which is neutral (neither

acid nor alkaline), corresponds to a

hydrogen ion concentration of 10–7

gram-

equivalents per litre. A pH of 0 corresponds

to a hydrogen ion concentration of 10–0

(= 1) gram-equivalents per litre. A solution

with a pH greater than 7 is said to be

alkaline, whereas a solution with a pH

less than 7 is said to be acidic (Figure 7.2).

In weathering, any precipitation with a

pH below 5.6 is deemed to be acidic and

referred to as ‘acid rain’.

The solubility of minerals also depends

upon the Eh or redox (reduction–oxida-

tion) potential of a solution. The redox

potential measures the oxidizing or

reducing characteristics of a solution. More

specifically, it measures the ability of a

solution to supply electrons to an oxidizing

agent, or to take up electrons from a

reducing agent. So redox potentials are

electrical potentials or voltages. Solutions

may have positive or negative redox

potentials, with values ranging from about

–0.6 volts to +1.4 volts. High Eh values

correspond to oxidizing conditions, while

low Eh values correspond to reducing

conditions.

Combined, pH and Eh determine the

solubility of clay minerals and other

weathering products. For example,

goethite, a hydrous iron oxide, forms

where Eh is relatively high and pH is

medium. Under high oxidizing conditions

(Eh +100 millivolts) and a moderate pH,

it slowly changes to hematite.

Box 7.2 pH AND Eh

Figure 7.2 The pH scale, with the pH of assorted

substances shown.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofgeomorphologyroutledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-220921044803-9a19de6c/85/fundamentalsofgeomorphology_routledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-pdf-160-320.jpg)

![Hydration

Hydration is transitional between chemical and

mechanical weathering. It occurs when minerals

absorbwatermoleculesontheiredgesandsurfaces,

or, for simple salts, in their crystal lattices, without

otherwise changing the chemical composition of

the original material. For instance, if water is added

to anhydrite, which is calcium sulphate (CaSO4),

gypsum(CaSO4.2H2O)isproduced.Thewaterinthe

crystal lattice leads to an increase of volume, which

maycausehydrationfoldingingypsumsandwiched

between other beds. Under humid mid-latitude

climates, brownish to yellowish soil colours are

caused by the hydration of the reddish iron oxide

hematitetorust-colouredgoethite.Thetakingupof

water by clay particles is also a form of hydration. It

leads to the clay’s swelling when wet. Hydration

assists other weathering processes by placing water

molecules deep inside crystal structures.

Oxidation and reduction

Oxidation occurs when an atom or an ion loses an

electron,increasingitspositivechargeordecreasing

its negative charge. It involves oxygen combining

with a substance. Oxygen dissolved in water is a

prevalent oxidizing agent in the environment.

Oxidation weathering chiefly affects minerals

containing iron, though such elements as

manganese, sulphur, and titanium may also be

oxidized.Thereactionforiron,whichoccursmainly

whenoxygendissolvedinwatercomesintocontact

with iron-containing minerals, is written:

4Fe2 + 3O2 + 2e → 2Fe2O3 [e = electron]

Alternatively, the ferrous iron, Fe2+

, which

occurs in most rock-forming minerals, may be

converted to its ferric form, Fe3+

, upsetting the

neutral charge of the crystal lattice, sometimes

causing it to collapse and making the mineral

more prone to chemical attack.

If soil or rock becomes saturated with stagnant

water, it becomes oxygen-deficient and, with the

aid of anaerobic bacteria, reduction occurs.

Reduction is the opposite of oxidation, and the

changes it promotes are called gleying. In colour,

gley soil horizons are commonly a shade of

grey.

The propensity for oxidation or reduction to

occur is shown by the redox potential, Eh. This is

measured in units of millivolts (mV), positive

values registering as oxidizing potential and

negative values as reducing potential (Box 7.2).

Carbonation

Carbonation is the formation of carbonates, which

are the salts of carbonic acid (H2CO3). Carbon

dioxidedissolvesinnaturalwaterstoformcarbonic

acid. The reversible reaction combines water with

carbon dioxide to form carbonic acid, which then

dissociatesintoahydrogenionandabicarbonateion.

Carbonicacidattacksminerals,formingcarbonates.

Carbonationdominatestheweatheringofcalcareous

rocks (limestones and dolomites) where the main

mineral is calcite or calcium carbonate (CaCO3).

Calcite reacts with carbonic acid to form calcium

hydrogencarbonate(Ca(HCO3)2)that,unlikecalcite,

is readily dissolved in water. This is why some

limestones are so prone to solution (p. 393). The

reversible reactions between carbon dioxide, water,

and calcium carbonate are complex. In essence, the

process may be written:

CaCO3 + H2O + CO2 ⇔ Ca2+

+ 2HCO3

–

This formula summarizes a sequence of events

starting with dissolved carbon dioxide (from the

air) reacting speedily with water to produce

carbonic acid, which is always in an ionic state:

CO2 + H2O ⇔ H+

+ HCO3

Carbonate ions from the dissolved limestone react

at once with the hydrogen ions to produce

bicarbonate ions:

CO3

2–

+ H+

⇔ HCO3

2–

This reaction upsets the chemical equilibrium in

the system, more limestone goes into solution to

144 PROCESS AND FORM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofgeomorphologyroutledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-220921044803-9a19de6c/85/fundamentalsofgeomorphology_routledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-pdf-161-320.jpg)

![The natural vegetation of the Southern Great Plains of Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico,

Oklahoma, and Texas is prairie grassland that is adapted to low rainfall and occasional

severe droughts. During the ‘Dirty Thirties’, North American settlers arrived from the

east. Being accustomed to more rainfall, they ploughed up the prairie and planted wheat.

Wet years saw good harvests; dry years, which were common during the 1930s, brought

crop failures and dust storms. In 1934 and 1935, conditions were atrocious. Livestock

died from eating excessive amounts of sand, human sickness increased because of the

dust-laden air. Machinery was ruined, cars were damaged, and some roads became

impassable. A report of the time evokes the starkness of the conditions:

The conditions around innumerable farmsteads are pathetic. A common farm scene

is one with high drifts filling yards, banked high against buildings, and partly or

wholly covering farm machinery, wood piles, tanks, troughs, shrubs, and young trees.

In the fields near by may be seen the stretches of hard, bare, unproductive subsoil

and sand drifts piled along fence rows, across farm roads, and around Russian-

thistles and other plants. The effects of the black blizzards [massive dust storms that

blotted out the Sun and turned day into night] are generally similar to those of snow

blizzards. The scenes are dismal to the passerby; to the resident they are demoralizing.

(Joel 1937, 2)

The results were the abandonment of farms and an exodus of families, remedied only

when the prairies affected were put back under grass. The effects of the dust storms

were not always localized:

On 9 May [1934], brown earth from Montana and Wyoming swirled up from the

ground, was captured by extremely high-level winds, and was blown eastward toward

the Dakotas. More dirt was sucked into the airstream, until 350 million tons were riding

toward urban America. By late afternoon the storm had reached Dubuque and

Madison, and by evening 12 million tons of dust were falling like snow over Chicago

– 4 pounds for each person in the city. Midday at Buffalo on 10 May was darkened

by dust, and the advancing gloom stretched south from there over several states,

moving as fast as 100 miles an hour. The dawn of 11 May found the dust settling over

Boston, New York, Washington, and Atlanta, and then the storm moved out to sea.

Savannah’s skies were hazy all day 12 May; it was the last city to report dust conditions.

But there were still ships in the Atlantic, some of them 300 miles off the coast, that

found dust on their decks during the next day or two.

(Worster 1979, 13–14)

Box 12.2 THE DUST BOWL

AEOLIAN LANDSCAPES 337](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofgeomorphologyroutledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-220921044803-9a19de6c/85/fundamentalsofgeomorphology_routledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-pdf-356-320.jpg)

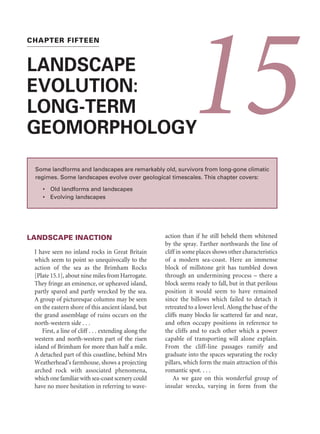

![LANDSCAPE INACTION

I have seen no inland rocks in Great Britain

which seem to point so unequivocally to the

action of the sea as the Brimham Rocks

[Plate 15.1], about nine miles from Harrogate.

They fringe an eminence, or upheaved island,

partly spared and partly wrecked by the sea.

A group of picturesque columns may be seen

on the eastern shore of this ancient island, but

the grand assemblage of ruins occurs on the

north-western side . . .

First, a line of cliff . . . extending along the

western and north-western part of the risen

island of Brimham for more than half a mile.

A detached part of this coastline, behind Mrs

Weatherhead’s farmhouse, shows a projecting

arched rock with associated phenomena,

which one familiar with sea-coast scenery could

have no more hesitation in referring to wave-

action than if he still beheld them whitened

by the spray. Farther northwards the line of

cliff in some places shows other characteristics

of a modern sea-coast. Here an immense

block of millstone grit has tumbled down

through an undermining process – there a

block seems ready to fall, but in that perilous

position it would seem to have remained

since the billows which failed to detach it

retreated to a lower level. Along the base of the

cliffs many blocks lie scattered far and near,

and often occupy positions in reference to

the cliffs and to each other which a power

capable of transporting will alone explain.

From the cliff-line passages ramify and

graduate into the spaces separating the rocky

pillars, which form the main attraction of this

romantic spot. . . .

As we gaze on this wonderful group of

insular wrecks, varying in form from the

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

LANDSCAPE

EVOLUTION:

LONG-TERM

GEOMORPHOLOGY

15

Some landforms and landscapes are remarkably old, survivors from long-gone climatic

regimes. Some landscapes evolve over geological timescales. This chapter covers:

• Old landforms and landscapes

• Evolving landscapes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofgeomorphologyroutledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-220921044803-9a19de6c/85/fundamentalsofgeomorphology_routledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-pdf-452-320.jpg)

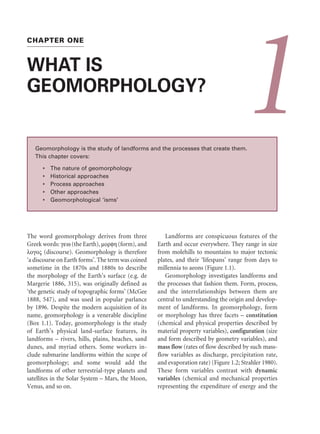

![442 PROCESS AND FORM

The study of Tertiary landscape evolution in southern Britain nicely shows how emphasis in

historical geomorphology has changed from land-surface morphology being the key to

interpretation to a more careful examination of evidence for past geomorphic processes. As Jones

(1981, 4–5) put it,

[this] radical transformation has in large part resulted from a major shift in methodology, the

heavily morphologically-biased approach of the first half of the twentieth century having

given way to studies that have concentrated on the detailed examination of superficial deposits,

including their faunal and floral content, and thereby provided a sounder basis for the dating

of geomorphological events.

The key to Wooldridge and Linton’s (1939, 1955) classic model of landscape evolution in Tertiary

south-east England was three basic surfaces, each strongly developed on the Chalkland flanks

of the London Basin (Figure 15.7). First is an inclined, recently exhumed, marine-trimmed surface

that fringes the present outcrop of Palaeogene sediments. Wooldridge and Linton called this the

Sub-Eocene Surface (it is now more accurately termed the Sub-Palaeogene surface). Second is

an undulating Summit Surface lying above about 210 m, mantled with thick residual deposits of

‘Clay-with-Flints’, and interpreted by Wooldridge and Linton as the remnants of a region-wide

subaerial peneplain, as originally suggested by Davis in 1895, rather than a high-level marine

plain lying not far above the present summits. Third is a prominent, gently inclined erosional

platform, lying between about 150 and 200 m and cutting into the Summit Surface and seemingly

truncating the Sub-Eocene Surface. As it bears sedimentary evidence of marine activity,

Wooldridge and Linton interpreted it as a Pliocene marine plain. Wooldridge and Linton believed

that the two higher surfaces – the Summit Surface and the marine platform – were not warped.

They argued, therefore, that these surfaces must have formed after the tectonic episode that

deformed the Sub-Eocene Surface, and that the summit plain had to be a peneplain fashioned

during the Miocene and Pliocene epochs.

The Wooldridge and Linton model of Tertiary landscape evolution was the ruling theory until

at least the early 1960s and perhaps as late as the early 1970s. Following Wooldridge’s death in

1963, interest in the long-term landform evolution of Britain – or denudation chronology, as many

geomorphologists facetiously dubbed it – waned. Critics accused denudation chronologists of

letting their eyes deceive them: most purely morphological evidence is ‘so ambiguous that

theory feeds readily on preconception’ (Chorley 1965, 151). However, alongside the denigration

of and declining interest in denudation chronology, some geomorphologists reappraised the

evidence for long-term landscape changes. This fresh work led in the early 1980s to the destruction

of Wooldridge and Linton’s ‘grand design’ and to the creation of a new framework that discarded

the obsession with morphological evidence in favour of the careful examination of Quaternary

deposits (Jones 1999, 5–6). The reappraisal was in part inspired by Philippe Pinchemel’s (1954)

alternative idea that the gross form of the Chalk backslopes in southern England and northern

Box 15.1 TERTIARY LANDSCAPE EVOLUTION IN SOUTH-EAST

ENGLAND

continued . . .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofgeomorphologyroutledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-220921044803-9a19de6c/85/fundamentalsofgeomorphology_routledgefundamentalsofphysicalgeography-pdf-461-320.jpg)