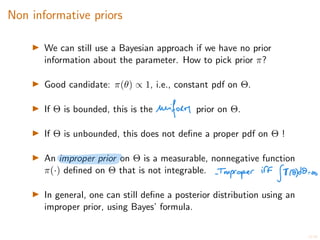

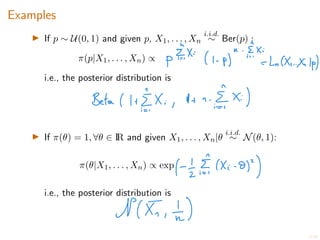

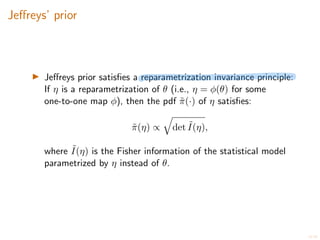

This document discusses Bayesian statistics and compares it to the frequentist approach. The Bayesian approach models uncertainty about parameters through prior distributions, which are updated based on data to obtain posterior distributions. This allows incorporation of prior beliefs. Key concepts covered include Bayes' formula, priors like non-informative and Jeffreys' priors, Bayesian estimation using the posterior mean or maximum a posteriori, and Bayesian confidence regions. Examples of applying Bayesian methods to binomial and normal distributions are provided.

![6/20

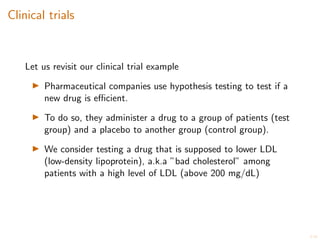

The kiss example

I Our prior belief about p can be quantified:

I E.g., we are 90% sure that p is between .4 and .6, 95% that it

is between .3 and .8, etc...

I Hence, we can model our prior belief using a distribution for

p, as if p was random.

I In reality, the true parameter is not random ! However, the

Bayesian approach is a way of modeling our belief about the

parameter by doing as if it was random.

I E.g., p ⇠ Beta(a, b) (Beta distribution. It has pdf

f(x) =

1

K

xa 1

(1 x)b 1

1

I(x 2 [0, 1]), K =

Z 1

0

ta 1

(1 t)b 1

dt

I This distribution is called the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatistics-bayesianstatistics-220724155034-ca6d8a11/85/Fundamentals-of-Statistics-Bayesian-Statistics-pdf-6-320.jpg)

![9/20

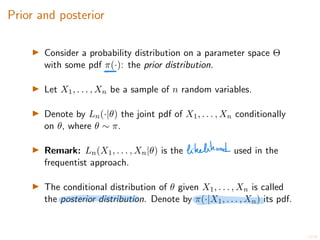

Clinical trials

I Let d > 0 denote the expected decrease of LDL level (in

mg/dL) for a patient that has used the drug.

I Let c > 0 denote the expected decrease of LDL level (in

mg/dL) for a patient that has used the placebo.

Quantity of interest: ✓ := .

In practice we have a prior belief on ✓. For example,

I ✓ ⇠ Unif([100, 200])

I ✓ ⇠ Exp(100)

I ✓ ⇠ N(100, 300),

I . . .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatistics-bayesianstatistics-220724155034-ca6d8a11/85/Fundamentals-of-Statistics-Bayesian-Statistics-pdf-9-320.jpg)

![17/20

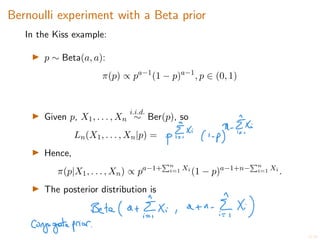

Bayesian confidence regions

I For ↵ 2 (0, 1), a Bayesian confidence region with level ↵ is a

random subset R of the parameter space ⇥, which depends

on the sample X1, . . . , Xn, such that:

IP[✓ 2 R|X1, . . . , Xn] =

I Note that R depends on the prior ⇡(·).

I ”Bayesian confidence region” and ”confidence interval” are

two distinct notions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofstatistics-bayesianstatistics-220724155034-ca6d8a11/85/Fundamentals-of-Statistics-Bayesian-Statistics-pdf-17-320.jpg)