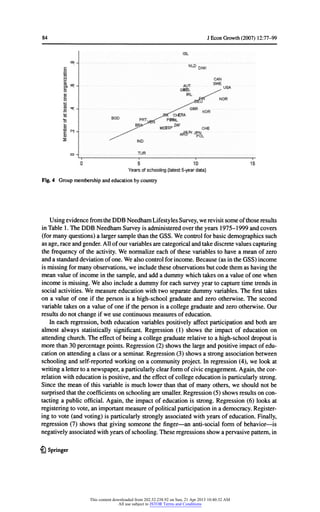

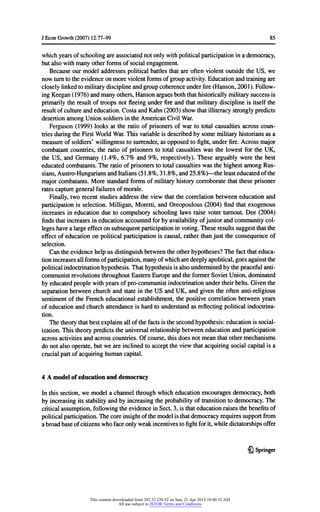

Education and democracy are highly correlated across countries. The author presents evidence that higher levels of education predict transitions from dictatorship to democracy over time. While some studies found no relationship when accounting for fixed country effects, more recent studies using different econometric techniques still find that education causes democracy. The author proposes a model where education increases civic participation, which favors democracy relative to dictatorship since democracy relies on broad civic engagement more than top-down incentives alone. As education increases participation, it makes democratic revolutions more likely to succeed against dictatorships and reduces the chances of anti-democratic coups.

![JEconGrowth(2007) 12:77-99 87

strongincentivesto a narrowbase of supporters.Educationraisesthebenefitsofpolitical

participationanddrawsrelativelymorepeopletosupportdemocracy.

4.1 Modelsetup

Thecountryis populatedbymeasureoneofhomogeneouscitizens,eachwitha humancap-

itallevelofh > 0.3 A regimeis definedas a setC/ ofinsiders,withg; 6 [0, 1] beingthe

measureoftheset,orthesize oftheregime.Weinterpreta largergj as a moredemocratic

regime.Wecall a regimewithg; = 1 a perfectdemocracy.

Inperiodzero,thereis an exogenousstatusquo regimeGo ofsize go.In periodone,an

alternativeregimeG ofsize gis proposed.Membershipineachregimeis exogenous.In

periodtwo,each individualchooseswhethertodefendtheexistingregime,tofightforthe

newregime,ortostaypoliticallyuninvolved.Individualsmaynotsupportbothregimes.In

thismodel,whileeachindividualtakesas givenhismembershipina particularregime(orin

neither),hestillchooseswhethertoparticipateinpolitics.

We letSi e [0,gj] denotetheendogenouslydeterminedmassofinsiderswhochooseto

supportregimeGj. The challengerunseatstheincumbentifandonlyifsqso 5 fi^i, where

Sj is a randomshocktotheeffectivenessofeachfaction'ssupporters.The ratiop = eo/s

hasa continuousprobabilitydistributionZ(p) onR+.

Each individualis of measurezero and so does notimpacttheprobabilitythateither

regimesucceeds.Individualsthereforedo notbase theirpoliticalparticipationdecisionson

theirimpacton theoutcome.Instead,participationin politicsis based on threedifferent

forces.First,regimesprovideincentivestotheirmembersto participate.These incentives

taketheformof punishinga regime'sinsiderswho do notfightforit (or,equivalently,

rewardingregimeinsiderswhodo comeoutandfight).Second,regimeinsiderswhopartici-

patethemselvesmotivatetheirfellowinsiderstojointhemthroughpersuasion,camaraderie,

orpeerpressure.Wemodelthisas a benefitfromparticipation(equivalently,itcanbe a cost

ofnon-participation,ifyourfriendsshameyouwhenyousitout).Wealso assumethatthere

areindividual-specificcostsofparticipation.Inourmodel,whatis crucialis thenetbenefit

ofparticipatinginpoliticsrelativetonotparticipating,so itdoes notmatterwhethereither

regime-levelorpeer-levelincentivestaketheformofpunishmentsorrewards.

Weformallymodela regime'spowertomotivateinsidersbyassumingthatinsiderswho

failto supporttheirregimesufferan expectedutilityloss describedby thecontinuously

differentiablefunctionp(gj) suchthatforall gi € [0, 1]

p(8i) >0 andp'(gi)<0.

Smallergroupsimposelargerpunishmentson free-riders:"thegreatereffectivenessof

relativelysmallgroups[. . .] is evidentfromobservationand experienceas well as from

theory"(Olson,1965,p.53). Smallergroupsbenefitfrombettermonitoringandpunishment

oftransgressors.As Olson (p. 61) writes,"In general,socialpressureandsocial incentives

operateonlyingroupsofsmallersize."Thisassumptionsetsupthebasic tradeoffbetween

smallerandlargerregimes.Smallregimesprovidestrongincentivestoa smallbase. Larger

(i.e.,moredemocratic)regimesprovideweakerincentivesbuttoa largerpotentialbase of

supporters.

Thethreatofpunishment(orthepromiseofrewards)capturestheglobalincentivespro-

videdbytheleaderstoallinsiders.Wealsoallowregimeinsiderswhoparticipatetomotivate

3 InBourguignonandVerdier(2000)politicalparticipationdependsoneducation,buteducationisdetermined

bytheinitialincomedistributionandparticipationincentivesarenotconsidered.

£} Springer

This content downloaded from 202.52.238.92 on Sun, 21 Apr 2013 10:40:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/foundationjournal-130520042342-phpapp01/85/Foundation-journal-12-320.jpg)

![88 JEconGrowth(2007) 12:77-99

theirpeerstodolikewise.Whiletheregime-levelmotivationshouldbethoughtofaslead-

ersthreateningmembers,wethinkofthislocalmotivationas friendsconvincingfriendsto

comeoutandfight.Preciselybecauseoftheirlocalnature,thesebenefitsdependnotonthe

aggregatesizeoftheregime,butontherateofparticipationa€[0,1],whichcapturesthe

shareoffriendswhoturnouttosupporta regimeandprovidemotivation,oridenticallythe

probabilitythateachfriendturnsout.

Wealsoassumethatthesebenefitsofparticipationarea functionofthehumancapi-

talofregimemembers,andspecificallythattheyarerepresentedbya twicecontinuously

differentiablefunctionb(ajh) suchthatb(0) = 0 andforalla€[0,1]andh > 0

baih)>0andZ/'(a,/0< 0.

Higherlevelsofhumancapitalmakepeoplebetteratinducingtheirpeerstoparticipate

politically.4AsdiscussedinSect.3,thisreflectsthetwofoldroleofeducationincreating

socialskills.First,moreeducatedpeoplearebetteratcajoling,encouraging,motivating,or

otherwisepersuadingotherstheyinteractwithtojointhem.Second,moreeducatedpeopleare

betterabletoreapthebenefitsofsocialinteractionthemselves,perhapsbecausetheyunder-

standbetterwhytheyareparticipating.Socializationcoversthetwinpowerstopersuadeand

tounderstand,bothcapturedbyb{.).Itismoreappealingtoparticipateinacollectiveactivity

themoreeducateda personis,andthemoreeducatedtheotherparticipantsare.

Offsettingtheglobalandlocalincentivesisaneffortcostcofpoliticalparticipation,which

isidenticallyandindependentlydistributedacrossallindividualswithcontinuousdistribu-

tionF(c). Thisidiosyncraticcostisrealizedatthestartofperiodtwo,aftermembershipin

thetworegimeshasbeendefined.

4.2 Groupequilibrium

Peerincentivesforparticipationdeterminea socialmultiplier,whichcouldbeunderstoodas

a bandwagoneffect.Themoreactivemembersagroupalreadyhas,themorelikelytopartic-

ipatetheremainingmembersare.Theparticipationratea, isthenendogenouslydetermined

asa functionoftheexogenousparametersgjandh.Ina groupequilibrium,

ai = F(p(gi)+ b(aih)).

Inprinciple,strategiccomplementaritycouldleadmultipleequilibria,someofwhich

wouldtypicallybeParetoranked(CooperandJohn,1988).Althoughcoordinationfailures

mayplayapartintheempiricaldeterminationofturnout,theyarenotcentraltoouranalysis.

Moreover,consideringa scenariowithoutcoordinationfailuresallowsustoestablisha more

robustlinkbetweeneducationandparticipation,beforetakingintoaccounttheroleofhuman

capitalinresolvingcoordinationfailures.

Hence,wemaketwoeconomicallyintuitiveassumptionsonthedistributionofcoststhat

guaranteeuniquenessofthegroupequilibrium:

Assumption1 c hasa connectedsupportC thatincludestherangeofp(g{) + b(cijh).

Assumption2 c has a continuouslydifferentiabledensityf(c) thatis monotone

non-increasing:f'(c) < 0 foreveryc eC.

4 Thereis nolossofgeneralityinhavingh enterlinearly,becausewechoosehowtomeasureh.Wecould

writeb{ath{H)), whereh(.) isanymonotoneincreasingfunctionandH isanothermorenaturalmeasureof

humancapital,suchas yearsofschooling.

£lSpringer

This content downloaded from 202.52.238.92 on Sun, 21 Apr 2013 10:40:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/foundationjournal-130520042342-phpapp01/85/Foundation-journal-13-320.jpg)

![JEconGrowth(2007) 12:77-99 91

gi*

1 I

0.8 . /

0.6 y^

0.4

"

j

- '^*~

0.2 .

0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

Fig.6 Thesizeofthemostdangerouschallengertoa go = 30%oligarchyas a functionofhumancapital

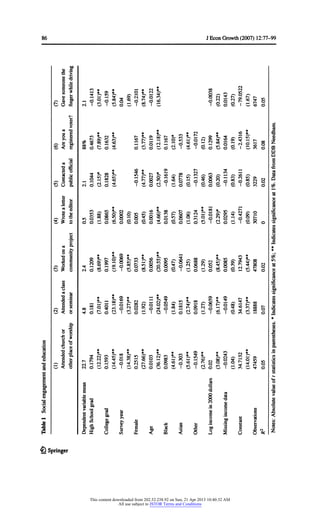

Proposition2 Consideran incumbentoligarchicregimeGo ofsize go e (0, 1]. Thesize

g* e (0, 1] ofthechallengerregimemostlikelyto overthrowGo is monotone(weakly)

increasinginthelevelofhumancapitalh.

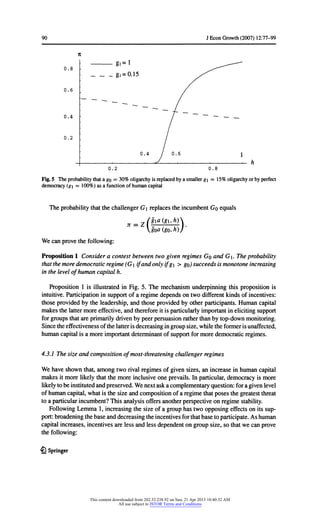

Proposition2 is illustratedinFigs.6 and7. As humancapitalincreases,thegreatestthreat

to an incumbentregimebecomesan evermoredemocraticregime.Therecan be a finite

levelofhumancapitalh(go) abovewhichthemostdangerouschallengerbecomesa perfect

democracy,g* = 1.

Butwhatisthecompositionofthemostthreateningregime?Fora fixedincumbentregime

Go,thesupportofa challengerGi dependsontwofactors:thesizeofitsmembershipgand

theextentoftheoverlapofthemembershipofthecompetingregimes.Recallingthaty isthe

measureofoverlap,theprobabilitythatthechallengerGreplacestheincumbentGo equals

ff_7/(gi-$)fl(g».*A

Fora challenger,recruitingmembersfromtheincumbentregimeratherthanamongthose

excludedfromithastwoopposingeffects:itstealssupportfromtheincumbent,butitalso

introducesa wedgebetweenthesize ofthechallengingregimeanditsownactualbasinof

support.Theresolutionofthistrade-offcomesfroma comparisonofthesizesofthecompet-

ingregimes.Thesmallerregimeismoreaffectedbythea priorilossofhalfoftheagentswith

dualmembership.Hence,a challengerregimethatismoredemocraticthantheincumbentis

morelikelytosucceedwhenitincludesall membersoftheincumbentitself.Conversely,a

lessdemocraticchallengerismorelikelytosucceedwhenitincludesas fewmembersofthe

incumbentregimeas possible(givenitssize). Formally,wecanprovethefollowing:

Corollary1 Consideran incumbentoligarchicregimeGo- The compositionofthemost

dangerouschallengercan be characterizedasfollows:

(1) ifthemostdangerouschallengeris less democraticthantheincumbent(g* < go),it

isminimallyoverlapping:thesizeofthegroupofcitizensbelongingtobothregimesis

y = max{0,gJe-(l

-

go)};

£}Springer

This content downloaded from 202.52.238.92 on Sun, 21 Apr 2013 10:40:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/foundationjournal-130520042342-phpapp01/85/Foundation-journal-16-320.jpg)

![92 JEconGrowth(2007) 12:77-99

Fig.7 Thesizeofthemostdangerouschallengertoa perfectdemocracy(go = 100%) asa functionofhuman

capital

(2) ifthemostdangerouschallengeris moredemocraticthantheincumbent(g* > go),it

isstrictlymoreinclusive:Go C G*.

AccordingtoProposition2, atlowlevelsofeducation,statusquo dictatorshipsaremost

effectivelychallengedbysmallcoups.Indeed,somehistoricalandstatisticalevidencesug-

geststhatchallengerstodictatorshipsinsuchcountriesareoftenbandsofdisgruntledoppo-

nents(CampanteandDo, 2005;Finer,1988;Huntington,1957).Athigherlevelsofeducation,

thesizesofoptimaluprisingsagainstbothdictatorshipanddemocracyrise.InEuropeduring

theage ofRevolutions,increasinglylargegroupsfoughttooverthrowtheexistingregime.

Similarly,revoltsagainstdemocracy,suchas theFascisttakeoverin Italyin the1920sor

theNazi movementin Germany,becameincreasinglybroad-basedin societieswithmore

education.

The Corollaryfurthertellsus that,as humancapitalincreases,notonlythesize butthe

natureofthemostdangerouschallengerchanges.Whenh is low,anincumbentdictatorship

ismostlikelytobereplacedbyanothersmalldictatorshipthatcomprisesa completelydiffer-

entsetofagents:thethreatcomesnotfroma subsetofthecurrentelitetryingto exclude

otherinsiders,butfromcurrentoutsiderstryingtooustthem.Whenhishigh,themosteffec-

tivechallengeris insteada (relatively)democraticregimethatdoes notattempttoremove

anyofthecurrentinsiders,butsimplytoadd morememberstotheregime.In thelimit,as

humancapitalrises,thegreatestthreattodictatorshipcomesfroma fulldemocracy,which

bydefinitionincludesthewholepopulation.

Anintermediatecase ispresentwhentheincumbentregimeislarge,go € (1/2,1].Inthis

case,themaximumprobabilityofsuccessmaycomefroma challengerthatincludesall the

currentoutsidersbutalso a subgroupofcurrentinsiders.Needlesstosay,thiscase istheonly

possibleone whentheincumbentregimeis a perfectdemocracy:thenanychallengercan

includeonlymembersofthecurrentregime.Forsufficientlyhighlevelsofhumancapital,the

highestprobabilityofsuccessisassociatedwithdemocraticturnover.Inotherwords,boththe

challengerandtheincumbentareperfectdemocracies,andcitizensfreelychoosetoaffiliate

witheithergroup.Our particularspecification,then,deliverstheoutcomeofcompetition

amongregimesperfectlycommittedtodemocracyathighenoughlevelsofhumancapital.

£} Springer

gi*

0.2 0.4 0.6 7 o78 r

0.8 /

0.6 /

0.4 /

0.2 __^--*^^

This content downloaded from 202.52.238.92 on Sun, 21 Apr 2013 10:40:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/foundationjournal-130520042342-phpapp01/85/Foundation-journal-17-320.jpg)

![JEconGrowth(2007) 12:77-99 95

whichistwicecontinuouslydifferentiablewithrespecttoa, becausesoareb andF. Omitting

argumentsforthesakeofbrevity,thefirstderivativeis

Qa = hfb'- 1

andthesecondis

Qaa=h2[f'{bf + fb"]<0

whosesignfollowsfromAssumption2.

Assumption1impliesfurthermorethat

Q(0g,h) = F(p(g))>0

Q(Ug,h) = F(p(g) + b(h))-l<0

andthereforebycontinuitythereexistsatleastoneroota e (0, 1).

Moreover,Q (0; g,h) > 0 impliesthatatthefirstrootQa (a;g,h) < 0. Concavitythen

impliesQa(a; g,h) < OVa> a, whichimpliesthattheroota is unique.Thecondition

Q(a;g,h)=0^Qa(a;g,h) < 0

canalsobe interpretedas showingthestabilityofthegroupequilibrium.

By theimplicit-functiontheorem,equilibriumparticipationis a differentiablefunction

a (g, h) suchthatQ (a (g, h) ; g, h) = 0. Since

Qg= fp'<o

Qh= afbf> 0

itsgradientis

da

_ Qg _ fp'

H Qa -hfb'

da

_ Qh = afbf

dh

_

Qa

=

1- hfb'

>

recallingthatQa < 0 inequilibrium.

A. 2 ProofofProposition1

Theimplicit-functiontheoremalsoallowsustocomputehigher-orderderivatives,andamong

these

d2d

= QQgh

~ QhQa QSa

-

QgQa Qha + QgQhQaa

SgSh Q

where

Qgh= af'p'b' > 0

Qga= hf'p'b' > 0

Qha= fb'+ ahf'(bf+ahfb"

£} Springer

This content downloaded from 202.52.238.92 on Sun, 21 Apr 2013 10:40:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/foundationjournal-130520042342-phpapp01/85/Foundation-journal-20-320.jpg)

![96 JEconGrowth(2007) 12:77-99

Therefore,

a2loga _ J/ j?a_ _ Sa_Sa

Sgdh ~a2dgdh

_ _

dgdh)

=

2753ia (Ql Qsh

- QhQaQga~ QgQaQha+ QgQhQaa) + QgQhQa]

*^a

=

JTp-{"Qo (QoQgh

-

QhQga)+ Qg[a {QhQaa- QaQha)+ QhQa]}

=^rW(°"hfbf)alf>pty+a2hfpftr{bf+fb"^

^p'(fb'+hf2b") o

(l-A/*03

Letfl,-=a(gi,h):ihe probabilityofvictoryforregimeGoverregimeGois

(gCt

1- I = Z (exp{log|i - loggo+ logai - logflo})

^0^0/

sothat

^L = - (h5l Jogii-iogJb+iogfli-logoo/81°g*l _ 81°gfl0

3A

=

VloflO/ V M

_

dh )

andthus

dn rt

-77-> 0rt4> gi > go

A.3 ProofofProposition2 andCorollary1

Recallthattheprobabilityofsuccessofa challengeris

(*o-£)«<«>,*)/

sothatthechallengerthatismostlikelytosucceedisthemaximizerof

M (g,y;go,h) = logo(g,h)+ logg

-

-j

- log^0

-

-r)

subjectto

gi €[0,1] andy €[max{0,gi - (1 - go)},min{g0,g}]

Tobeginwith,since

theoptimalvalueofy isindefiniteifg= goanditliesina cornerifg^ go.

Hencetheoptimalregimesizeis

8*(80,h) = arg max {loga (guh) + X(gi,go)}

£l€[0,l]

whereX(gi,go)isdefinedbythejointlyoptimalchoiceofoverlapy.

£}Springer

This content downloaded from 202.52.238.92 on Sun, 21 Apr 2013 10:40:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/foundationjournal-130520042342-phpapp01/85/Foundation-journal-21-320.jpg)

![JEconGrowth(2007) 12:77-99 97

TherearetwodifferentcasesbasedonthesizeoftheincumbentGo:smallgo€(0, j or

largego€(j, l]. Thefirstwillonlyhavetwopotentialcornersolutionsforoptimaloverlap:

y = 0 andy = go;thelatterwillalsohavethepossibilityofy = g- (1 - go) > 0.

1. Ifgo€(0,j] theoptimaloverlapis

gi e [0,go)

[0,go] g= go

go g€(go,1]

andtherefore

w« o flog^i - loggo gi €[0,g0]

^'^-llog^-fj-logf

w« o

g!€[gO,l]

a continuousfunctionthatismonotoneincreasingingandpiecewiseconcaveingfor

gi €[0,go]andge [go,1],butwitha convexkinkatg= go

2. Ifgo€(5, l] theoptimaloverlapis

0 gi e [0,1- g0]

v(o-yKgx)~

£i-0 -So) Si€[l-go,go)v(o-yKgx)~

[2go-l,go] gi=go

go 8€(go,1]

andtherefore

- loggo g€[0,1- g0]

Iloggi

log£rz|Q±i_log£Qz|i±i gl€[l-go,go]

log(gi-f)-logf Si€[go,l]

a continuousfunctionthatismonotoneincreasingingandpiecewiseconcaveingfor

g€[0,go]andg€ [go,1],butwitha convexkinkatg= goanda concavekinkat

g= 1- go-

Givenanygo€(0, l],g*(go,h) e (0,1]iswell-definedasthemaximandofacontinuous

functionona compact.ConsidertwolevelsofhumancapitalHl < h^. Supposethat

g*L= g*(go,hL) > g*(go,hH) ssg^

Thisimpliesbydefinitionthat

( log*(gl hL)+ k(gl go) > loga (g*H,hL)+ X(g*H,go)

1log*(g^, hH)+X(g*H,go) > oga(gl hH)+ X(gl go)

andthereforerearranging

logo(gl, hi)-oga (g*HihL)>X (g*H,go)-X (gl go)>oga (g*L>hH)-oga (g*H,hH)

andfinally

loga (g*H,hH)

- loga (g*HihL) > logfl(gl hH)

~ oga(gl hL)

ButintheproofofProposition1weestablishedthat

a^iog.

dgdh

whichprovesbycontradictionthat

hL <hH=>g$ (go,hL) < g*(go,hH)

£lSpringer

This content downloaded from 202.52.238.92 on Sun, 21 Apr 2013 10:40:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/foundationjournal-130520042342-phpapp01/85/Foundation-journal-22-320.jpg)