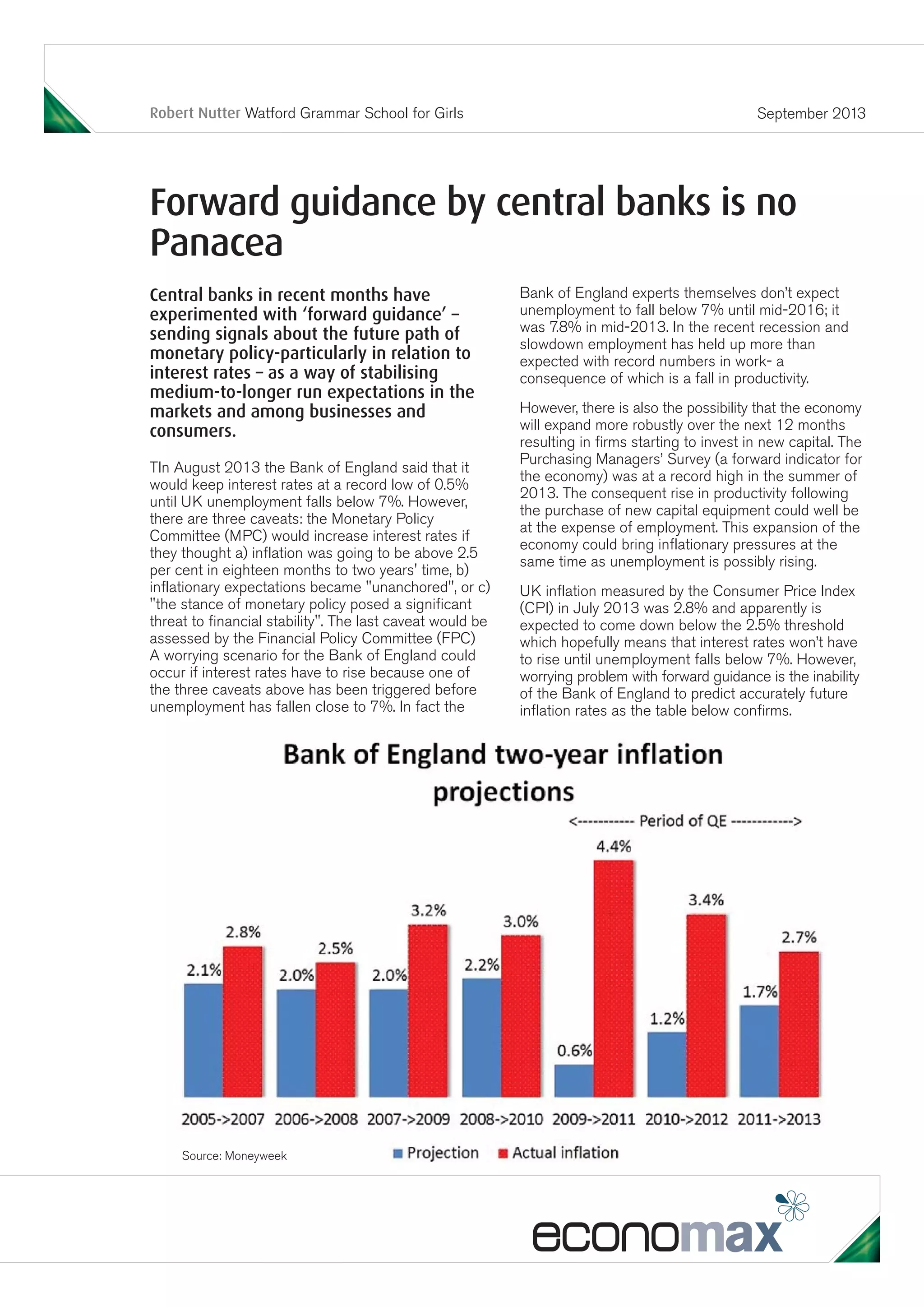

The document discusses the concept of 'forward guidance' in monetary policy, particularly by central banks like the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve, to stabilize market expectations regarding interest rates. It highlights the potential challenges of predicting future inflation and the risks associated with rising interest rates before unemployment falls to target levels. Ultimately, it concludes that while forward guidance can provide some stability, it is not a comprehensive solution to underlying economic issues.