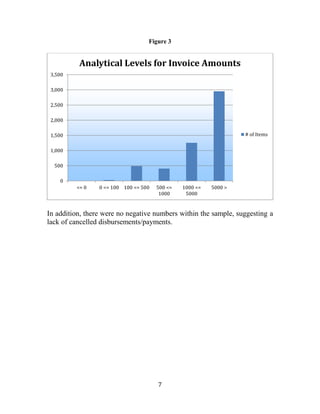

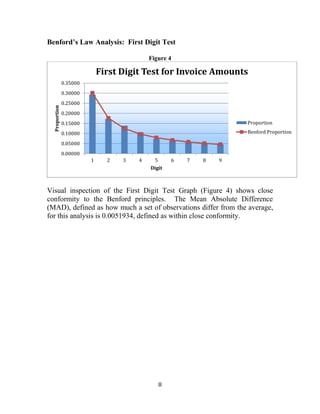

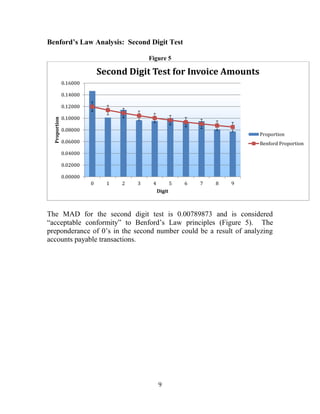

This document discusses using Benford's Law, a mathematical theory of leading digits, to analyze accounts payable transactions data from the District of Columbia's Department of Transportation for fiscal year 2013. Benford's Law predicts the distribution of leading digits in data sets and can help detect fraud by identifying anomalies. The document provides an overview of Benford's Law and its constraints, and presents a pilot analysis of the Department of Transportation disbursement data, which had 5,131 transactions totaling $376 million. Going forward, the methodology will be discussed with the Office of Integrity and Oversight to develop proper policies and procedures for using this fraud detection technique.