This document discusses teaching to the test, where teachers focus instruction on material that will be covered on high-stakes exams. It presents evidence that the pairing of predictable state exams and incentives for schools has increased pressure on teachers and led to more teaching to the test. The document proposes two mathematical models to study this phenomenon: 1) a Stackelberg Security Game model of exam creation, where teachers predict untested topics and remove them from curriculum; and 2) a knapsack problem model to quantify the effect of optimal time allocation to maximize exam scores based on learning curves and content. The models aim to provide insight into reducing consequences of teaching to the test and its effects on curriculum.

![List of Figures

1.1 Case study provided by Jennings and Bearak [9] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

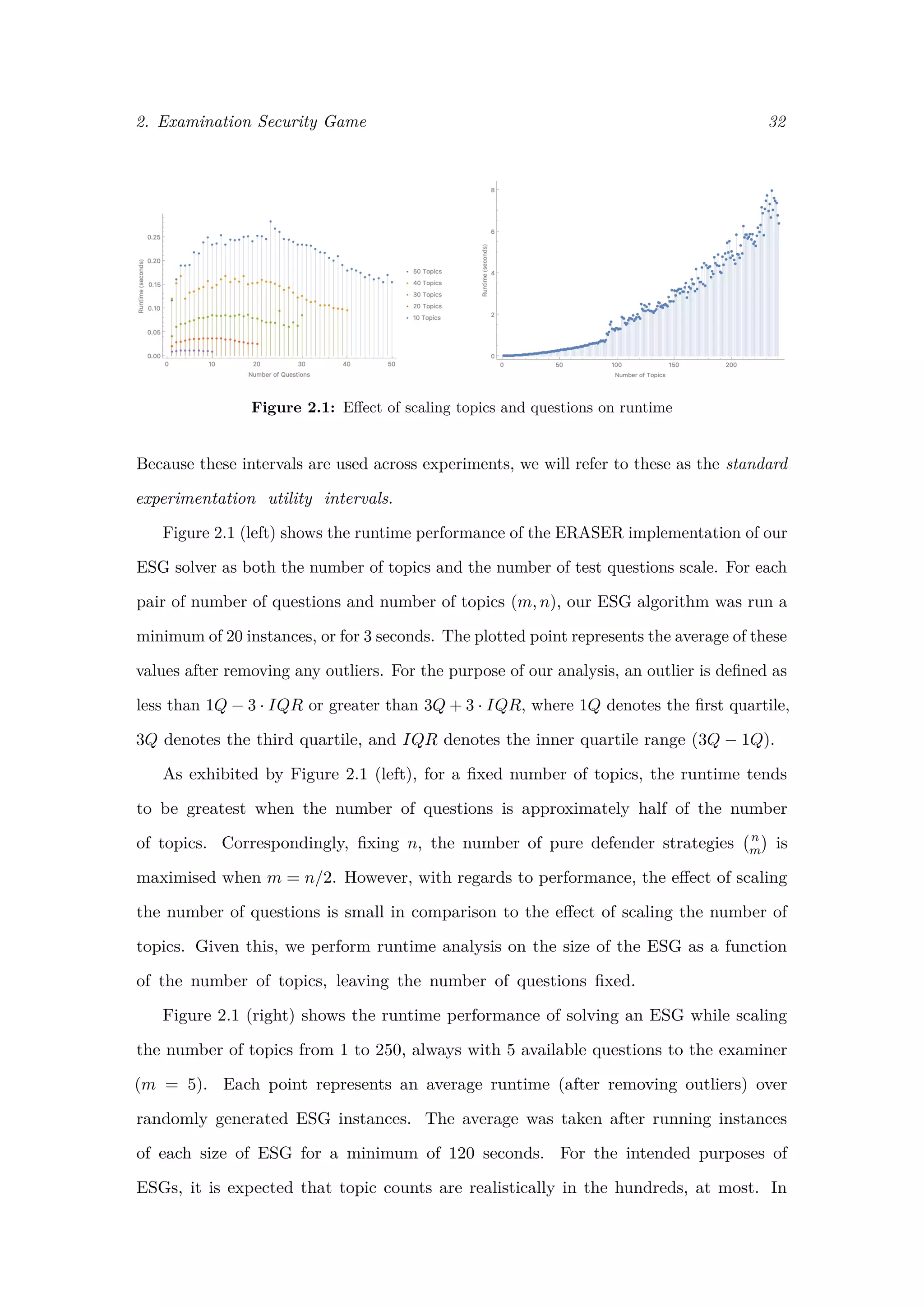

2.1 Effect of scaling topics and questions on runtime . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

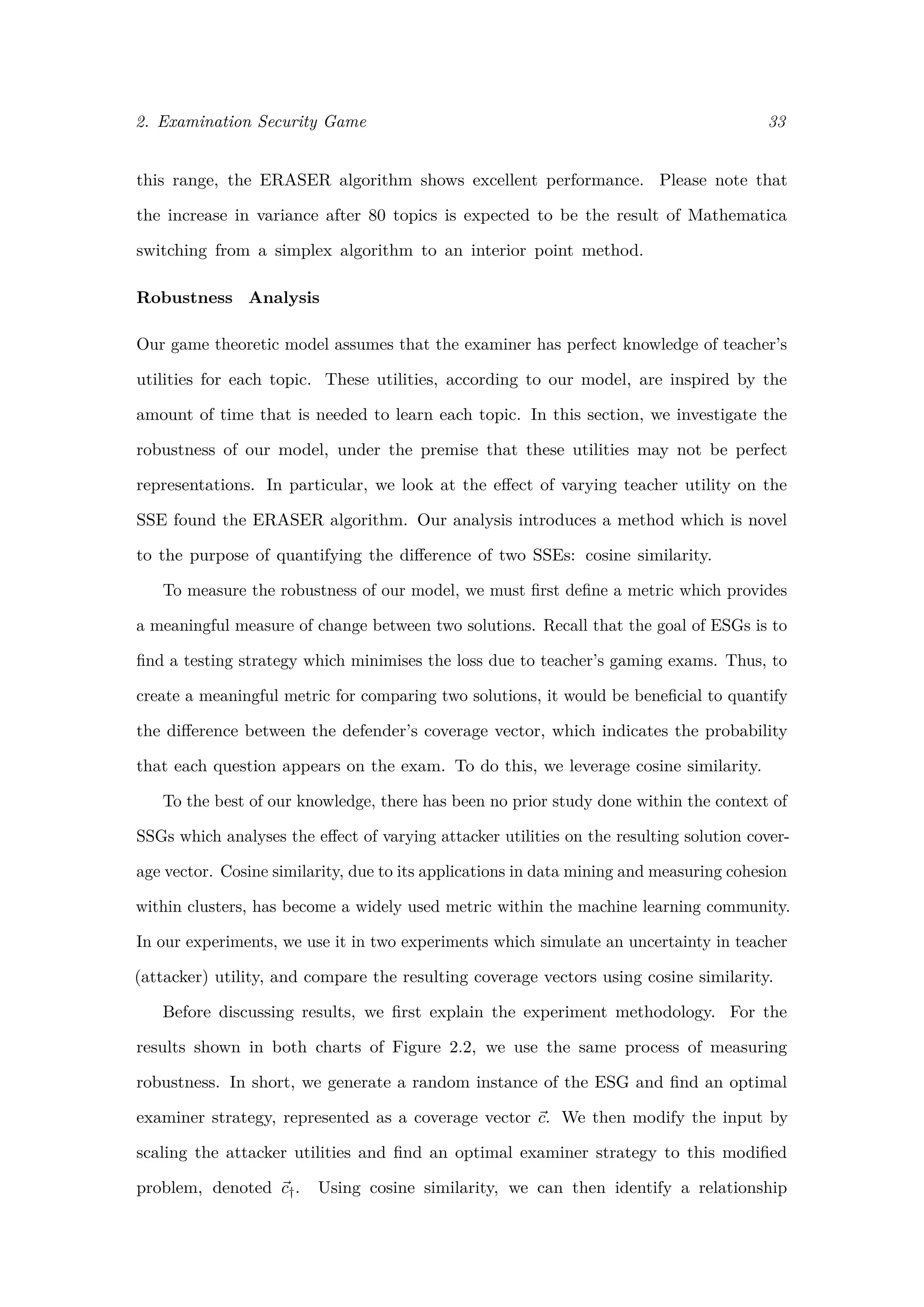

2.2 Uncertainty and coverage Similarity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

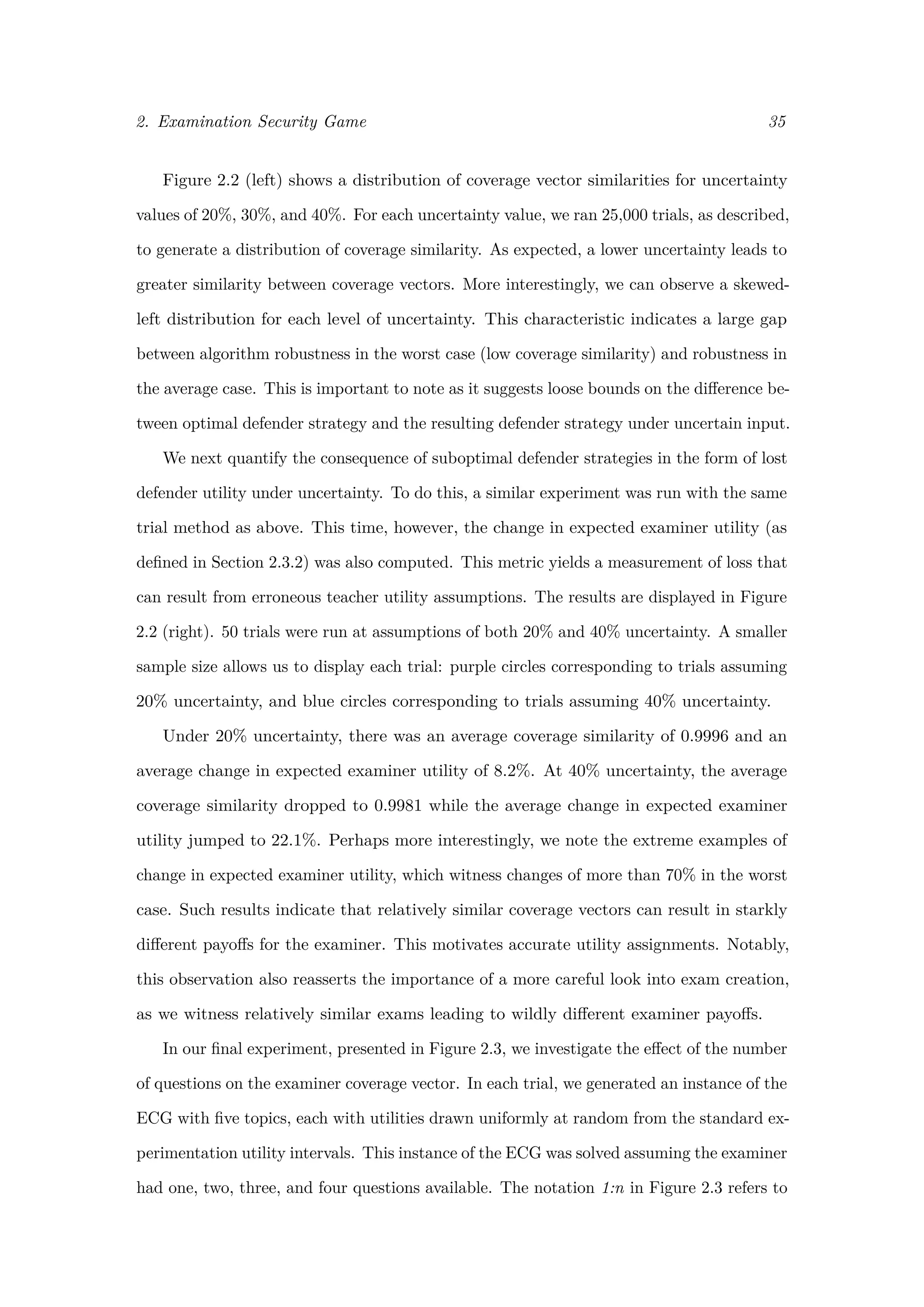

2.3 Effect of the number of questions on coverage similarity . . . . . . . . . . 36

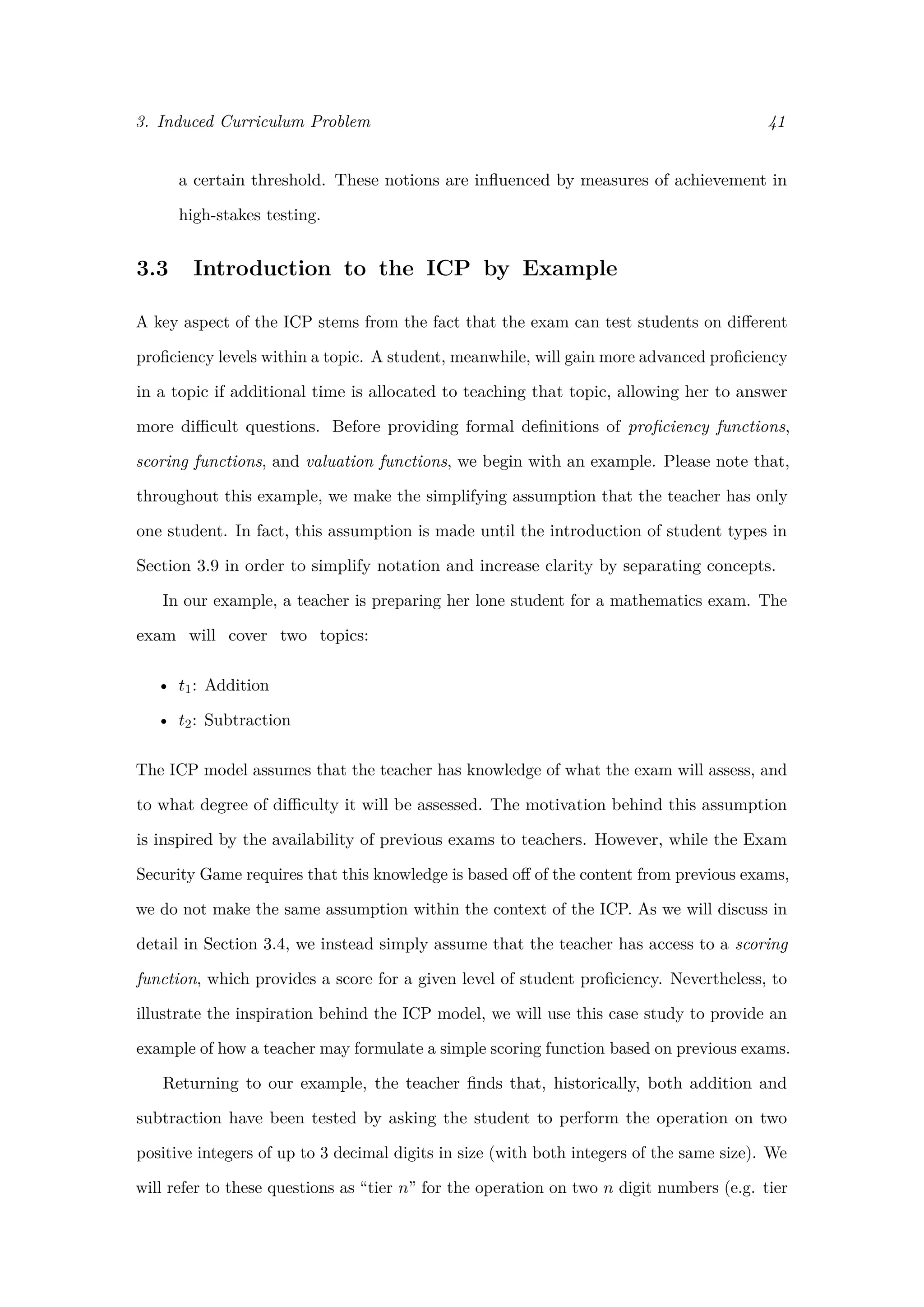

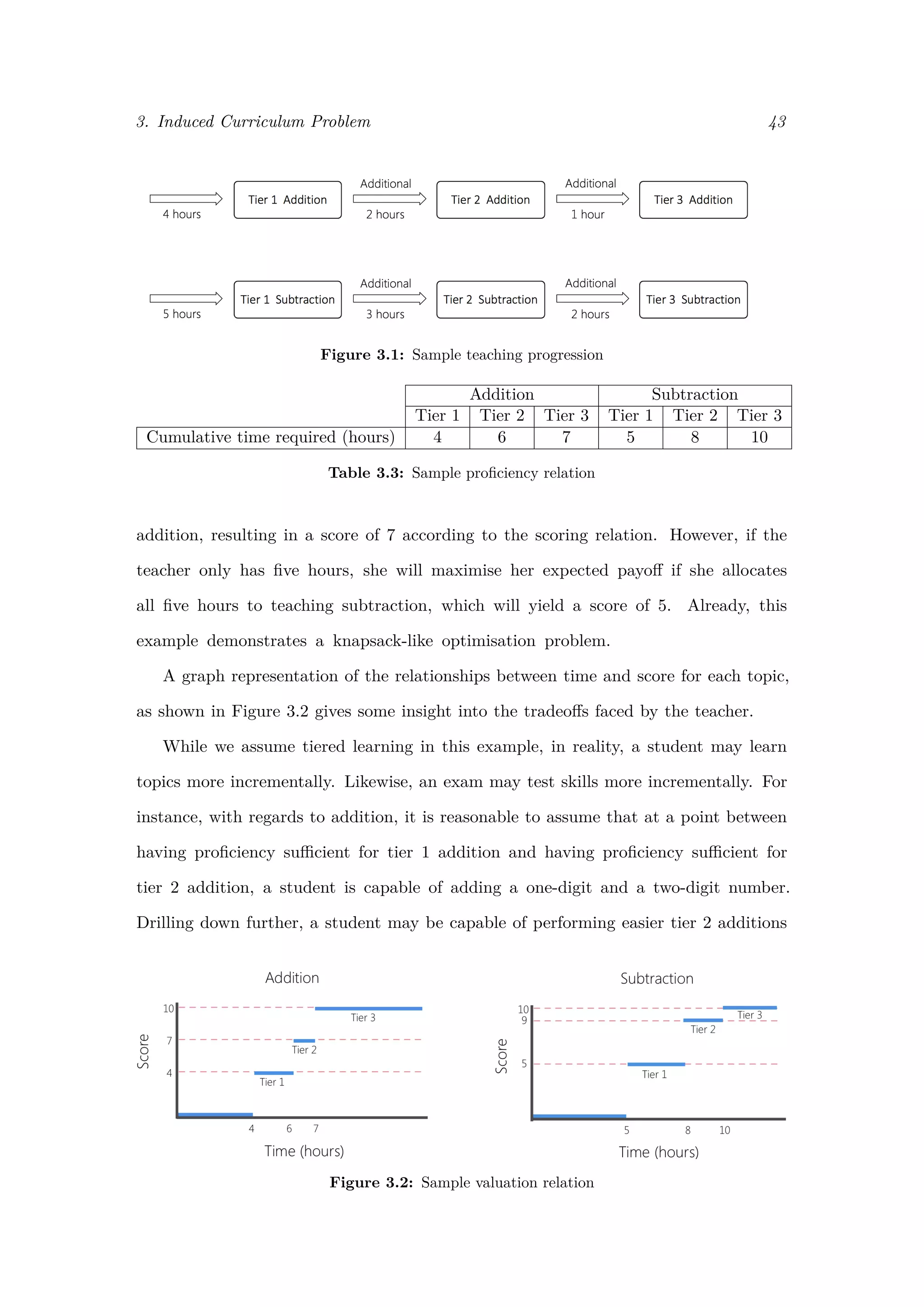

3.1 Sample teaching progression . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

3.2 Sample valuation relation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

3.3 Formation of linear valuation functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

3.4 Formation of 0-1 valuation functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

3.5 Formation of stepped valuation functions with granular time allocation . . 55

3.6 Formation of stepped valuation functions with stepped scoring . . . . . . 56

3.7 Graph representation of stepped valuation function . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

3.8 Separate, stacked, and tree topic structures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

3.9 Splitting a topic structure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

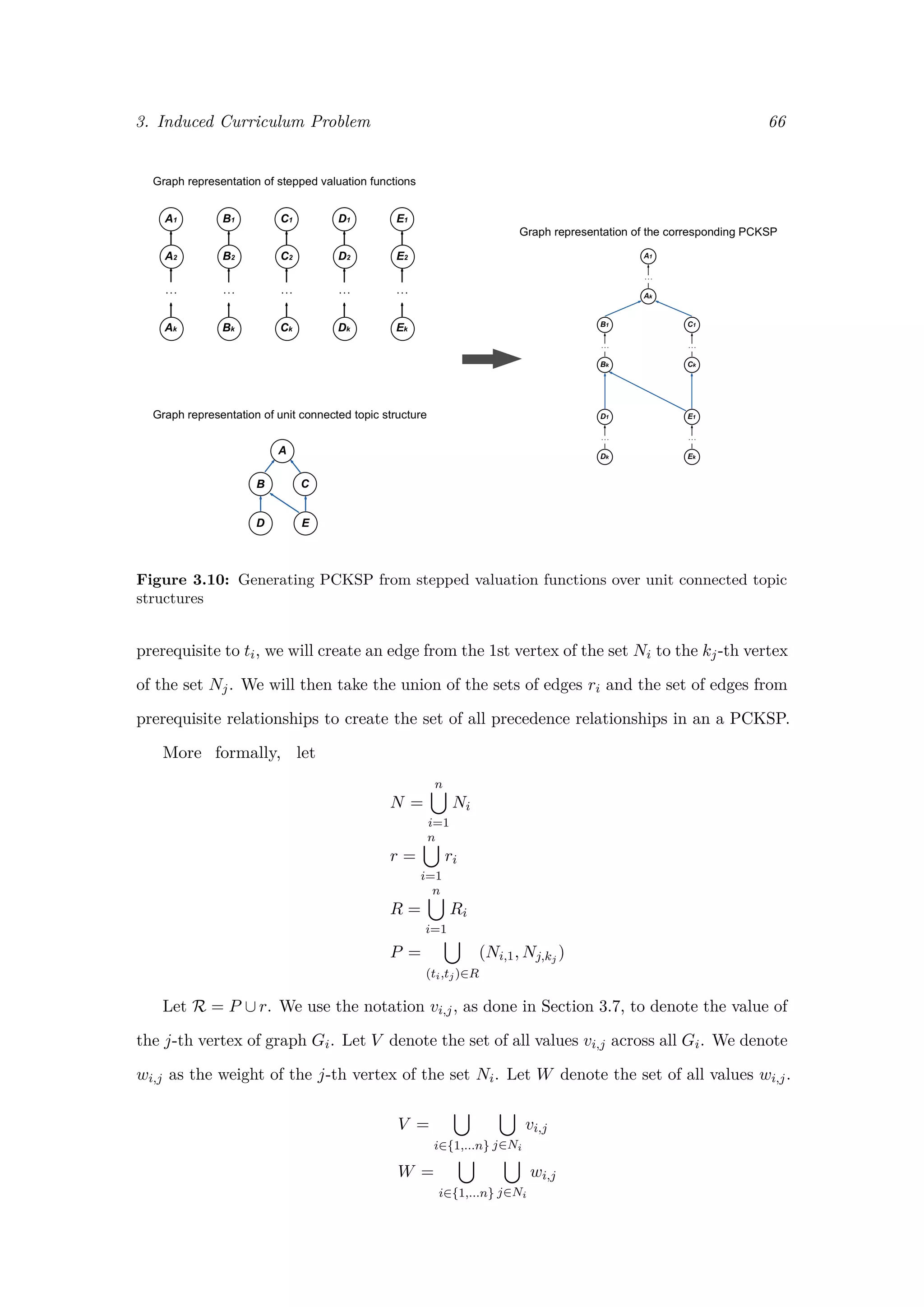

3.10 Generating PCKSP from stepped valuation functions over unit connected

topic structures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

vi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-6-2048.jpg)

![1Introduction

8.A.8 Multiply a binomial by a monomial or a binomial (integer coefficients)

8.A.11 Factor a trinomial in the form ax2 + bx + c; a = 1 and c having no more than three

sets of factors

In 2006, the New York State Department of Education listed these two items un-

der the “Algebra Strand” of the Grade 8 mathematics standards [1]. The standards

made no indication of relative importance, nor any recommendation on how much

time should be allocated to teaching each item. In the first four years after the

release of these standards, the first item was tested six times in the annual state

issued examination. The second item was not tested at all.

In 2007, the same New York State Department of Education initiated a program

which offered $3,000 per union teacher to schools which were able to meet goals of student

achievement, measured according to state issued examinations [2]. With this, the situation

in New York created a setting ripe for a practice known as teaching to the test.

Of course, the pairing of predictable state issued examinations and state issued

incentives (or accountability measures) is not one that is at all unique to New York.

Across the globe, the rise of high-stakes testing has placed considerable pressure not

only on students, but also on teachers and school administrators. As a result, recent

years have witnessed growing evidence of teaching to the test [3].

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-7-2048.jpg)

![1. Introduction 2

While case-based evidence is essential for diagnosing and monitoring this phenomenon,

it is typically costly and can, at times, be detrimental to the natural flow of the education

process. Our research aims to create models which embody the globally present interaction

between examination writers and teachers. To achieve this, we leverage two well-studied

mathematical problems: the Stackelberg Security Game and the knapsack problem.

In Chapter 2, we use Stackelberg Security Games (SSGs) to model the challenge faced

by examination writers in creating tests which are intended to assess student proficiency

across a full gamut of curriculum topics with only a limited number of questions. Since

2008, SSGs have established themselves as a powerful framework for generating security

strategies that have been implemented, with great success, by agencies including the US

Coast Guard and Federal Air Marshal Service [4, 5]. In our model, teachers use previous

exams to predict which topics will not be covered on the test, allowing these topics to be

removed from the class curriculum. The examination writer, on the other hand, must

create a test which is unpredictable, yet takes into account the relative importance of

topics. We create a model enabling us to cast this scenario to a Stackelberg Security

Game. Additionally, we present the first publicly available solver for SSGs, and provide

a novel analysis on the robustness of the model to uncertain inputs.

In Chapter 3, we formulate a problem whose solution is intended to quantify the effect

of teaching to the test on classroom curricula. Assuming that the teacher has knowledge

of what material will be tested, we use generalisations of the knapsack problem to find the

optimal allocation of class time amongst the set of curriculum topics. The solution to our

proposed problem maximises student exam scores, taking into account student learning

curves and exam content, simulating an instructor who perfectly teaches to the test. To al-

low for modeling of more complex scenarios, we introduce the notions of question difficulty,

prerequisite topics, and different student types who all exhibit distinct learning curves.

In this introductory chapter, we present the motivation behind our analysis. We

describe the role of assessments in education systems and how they are used to provide

measures of school and teacher accountability. We present evidence of the pressure which

high-stakes testing places on teachers, and discuss several means of gaming the system used

to boost examination scores. In particular, we focus on a form of gaming the system which](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-8-2048.jpg)

![1. Introduction 4

1.2 The Role of Assessments

The primary purpose of assessments is to provide an accurate measure of student

attainment. Assessments in the form of written exams are a particularly cheap and

efficient attempt at fulfilling this purpose. While exams importantly provide feedback

to both students and teachers on learning progress, the impact of test scores can reach

far beyond classroom walls. With specific regard to national exams, David Bell, former

Permanent Secretary at the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF), states:

We want [national exams] to provide objective, reliable information about

every child and young person’s progress. We want them to enable parents to

make reliable and informative judgements about the quality of schools and

colleges. We want to use them at the national level, both to assist and identify

where to put our support, and also, we use them to identify the state of the

system and how things are moving [3].

Drawing from Bell’s statement and a 2008 report released by the Children, Schools, and

Families Committee [3], we assemble a non-exhaustive list of usages of test results within

the UK:

1. Student qualification. Standardised testing provides a means of ranking students

across the nation. Results can be considered (non-exhaustively) in (i) diagnosing

learning difficulties and need for intervention and special resources; (ii) determining

a student’s readiness to move on to the next level of education; and (iii) measuring

a student’s qualification for a vocational position.

2. Teacher and school accountability. Student test scores are accumulated and

used to provide standardised indicators for class and school performance. These

results give insight into which schools require government interaction due to poor

performance.

3. Performance tables. Each year the UK Department of Education uses national

test results to publish data on student attainment. These league tables are widely

used by parents to compare and select schools for their children.

While the merit of using a single national test to simultaneously serve as a multi-

objective indicator has been questioned [3], the current state of affairs in the UK](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-10-2048.jpg)

![1. Introduction 5

routinely witnesses national tests which providing input into all three of the above

objectives. This procedure, which is certainly not unique to the UK, results in test

scores which are impactful on individual, local, and national levels.

1.3 Gaming the System

The term high-stakes testing is used to capture the weighty consequences of test scores,

generally with reference to nationally-administered standardised exams. While pressure

on students likely comes as no surprise, the accountability procedures, as described above,

place comparable pressure on teachers. In a 2015 survey [6], a UK teacher explains :

[In my previous school] there was an inordinate amount of pressure put on

teachers to ensure that students achieved their target grades.

As a result of the high stakes faced by students and teachers alike, instructors have

turned to exam-specific methodologies for improving test scores.

1.3.1 Various Forms of Gaming the System

While exams are intended to provide an accurate measure of student attainment, they

undoubtedly cause unwanted side effects in the form of distorted curricula, time spent

reviewing marking rubrics, and turning to revision guides instead of textbooks. We

refer to gaming the system as an examination-specific practice which intends to im-

prove test results without achieving an overall greater understanding of course ma-

terial for the student (a definition inspired by [3, 6, 7]).

While some strategies for gaming the system exhibit a clearly dubious ethical nature,

Dr. Michelle Meadows, of the University of Oxford, explains that other methods

find themselves in a grey zone of questionable conduct, whose effects on education

are difficult to gauge. Drawing from Meadows’ report [8] and an additional report

by Jennifer Jennings and Jonathan Bearak, of New York University [9], we compile

a non-exhaustive list of strategies for gaming the system:

1. Explicit cheating: This encapsulates any clear unethical behaviour on the part

of the teacher or student. For example, a administering a test can change students’

answers after collection or give out hints during the exam.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-11-2048.jpg)

![1. Introduction 6

2. School-wide decisions: With full knowledge of the consequences of poor national

test scores, schools may consider switching to easier exam boards or making changes

to which exam subjects they offer [8, 9].

3. Test Coaching: This covers a range of strategies from familiarising students with

test formats to providing students with frameworks to use during the standardised

exams [8].

4. Teaching to the test: While its usage varies across literature, we define teaching

to the test as an intentional modification of curriculum with the sole intent of

improving test scores based on the topics which are more likely to appear on the

test.

This research focuses specifically on the last mentioned strategy of gaming the system:

teaching to the test.

1.4 Teaching to the Test

All things considered, teaching to the test is widely viewed as an effective means of

raising test scores [3, 6, 7, 9]. The primary cause of its effectiveness is the predictability

of exams. Spark Notes LLC, a leading provider in test preparation material, makes

this statement about the SAT II Biology exam, a national standardised test whose

results are used to determine a student’s university readiness:

The SAT II Biology test has some redeeming qualities. One of them is

reliability. The test doesn’t change much from year to year. While individual

questions will never repeat from test to test, the topics that are covered and

the way in which they’re covered will remain constant.

Daniel Koretz of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, attributes the predictabil-

ity of exams to two main factors, summarised below [10]:

1. The challenge faced in forming questions of a desired difficulty level which accurately

assess student understanding. Exam questions which proved to give an accurate

measure of student attainment in previous years serve as excellent models for quickly

and cheaply writing new questions [10].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-12-2048.jpg)

![1. Introduction 7

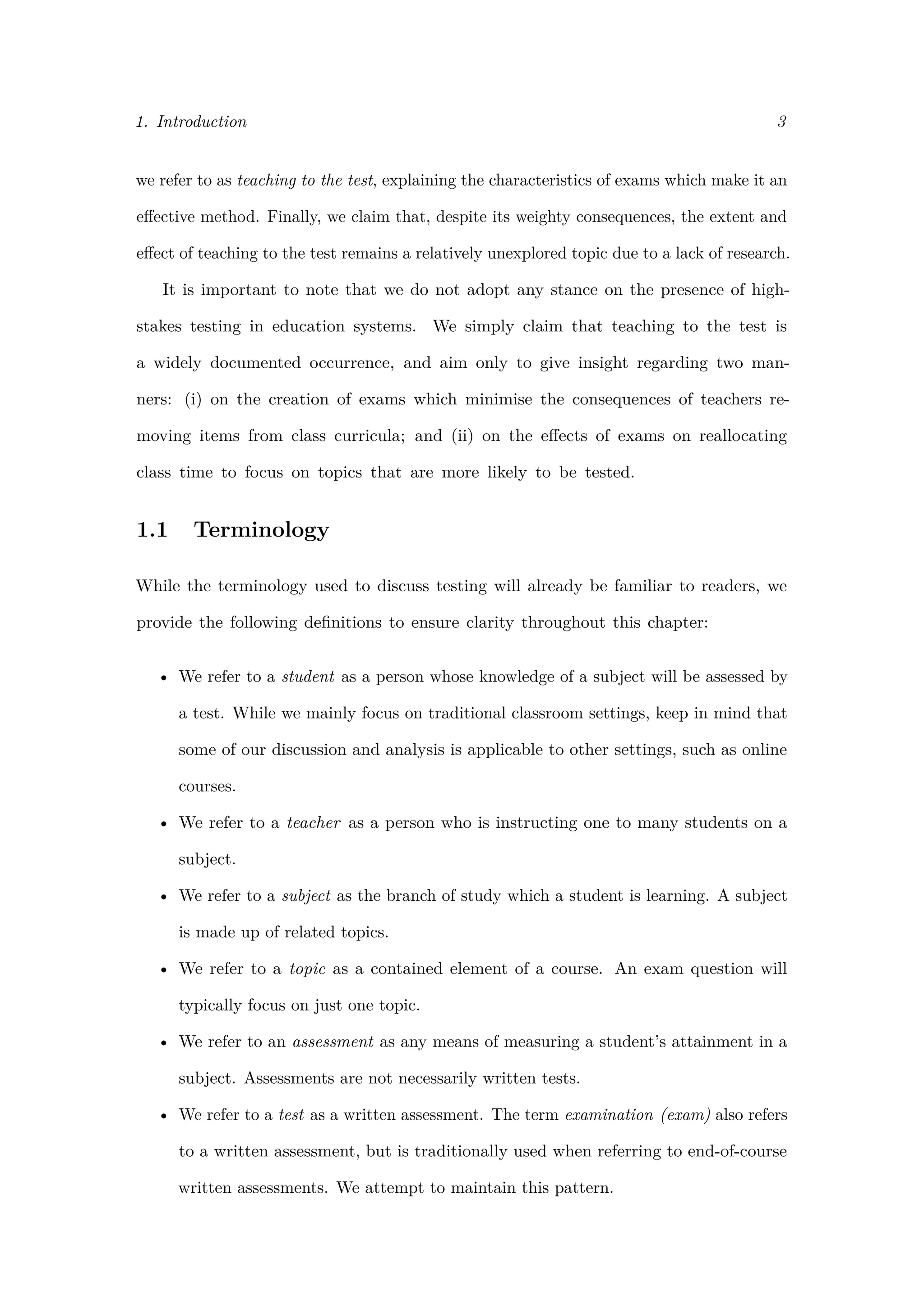

Figure 1.1: Case study provided by Jennings and Bearak [9]

2. The desire for consistent test difficulty across years. Failure to meet this requirement

has resulted in protests from students, teachers, and parents in the past [10].

Creating exams is an exercise in sampling. Due to time constraints, it is not possible

to cover all curriculum topics on an exam. Furthermore, any randomisation of test

material must take into account the relative importance of different topics, and the

need to keep some notion of similarity between exam iterations.

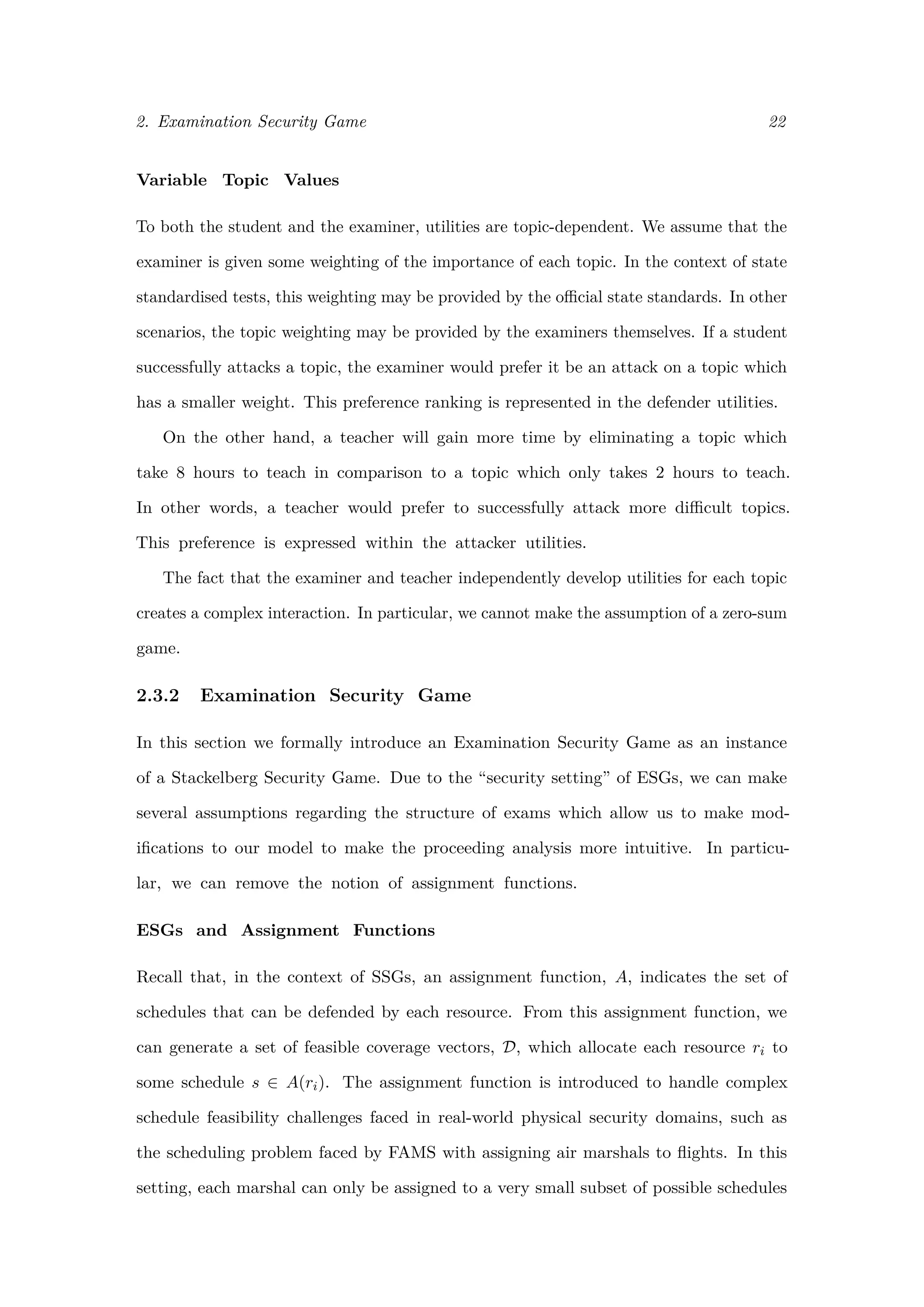

A report from Jennings and Bearak [9] provides a comprehensive study of topic

coverage on US standardised exams across three states over four years. In particular,

this study serves to prove the substantial advantage that can be gained by teaching to

the test. Table 1.1 shows their results, as presented in the original study [9]:

In New York ELA exams and New York and Massachusetts mathematics exams over

the four years spanning 2006 to 2009, less than two-thirds of all standards appeared on

any assessment. By eliminating these untested standards from class curricula, instructors

can allocate more time to teaching standards which are more likely to be tested. We

refer to this as narrowing the curriculum, where teaching to the test sacrifices breadth

of learning for depth of learning, focusing on topics that are more likely to appear

on exams. This type of teaching to the test is investigated in depth in Chapter

2. In general, however, teaching to the test can result in many forms of distorted

curricula. This more general consequence is studied in Chapter 3.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-13-2048.jpg)

![1. Introduction 8

1.5 Our Contributions

A 2008 report released by the Children, Schools, and Families Committee of the UK

House of Commons made the following statement on teaching to the test [3]:

We recommend that the Government reconsiders the evidence on teaching

to the test and that it commissions systematic and wide-ranging research to

discover the nature and full extent of the problem.

A proper system for education needs little in the way of an introduction regarding its

benefits worldwide. Teaching to the test is a practice which introduces an unknown

factor into education systems, jeopardising its effectiveness. The House of Commons

report reiterates the need to better understand its implications.

The research that we present takes two very distinct, but well-studied mathematical

problems, and applies them both within the context of student assessments with the

goal of providing insight into the growing problem of teaching to the test.

Examination Security Game

In Chapter 2, we introduce the Examination Security Game (ESG), which models the

interaction between an examiner and a teacher as a Stackelberg Security Game (SSG). In

traditional applications, SSGs model the interaction between an attacker and a defender.

The defender wishes to optimally allocate a limited number of security resources across

a set targets, each of which has a distinct value. The attacker, on the other hand,

can observe the defender’s strategy and plan her attack accordingly. The attacker also

has her own set of target values, distinct from those of the defender. Knowing that

the attacker has full observational capabilities, the defender must develop a security

strategy which is unpredictable, yet still accounts for target values. SSGs have been

implemented with great success in a range of applications facing this challenge [4, 5,

11–15], speaking to their ability to contribute in real-world scenarios.

The development of our ESG model serves as a major contribution of this chapter.

In particular, we show that the same critical assumptions of an SSG hold within the

examiner-teacher setting. Notably, the examiner plays the role of the defender and must

use a limited number of exam questions to cover a large bank of topics. The teacher,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-14-2048.jpg)

![1. Introduction 9

on the other hand, plays the role of the attacker, using past exams to predict which

topics will be tested. Claiming that critical assumptions of an SSG hold, we further assert

that the solution to the Examination Security Game yields an optimised strategy for

creating unpredictable exams which minimise the effects of teaching to the test.

Secondly, we implement an algorithm for solving SSGs that was proposed by Kiek-

intveld et al. [16]. We provide an implementation in Mathematica which is used in our

experimental analysis. Additionally, we provide an implementation coded in JavaScript.

To the best of our knowledge, no solver for the SSG has previously been made publicly

available. Furthermore, research within recent literature often makes use of IBM’s

CPLEX studio, a costly optimisation software product. Because of the incredible range

of applications of SSGs, we wanted to provide a more accessible alternative to using

an expensive solver. Our JavaScript implementation serves this purpose.

Finally, we present and analyse the results from a number of experiments. Notably,

we present novel analysis on the robustness of SSGs under the assumption of uncertain

inputs. We leverage cosine similarity as a metric of similarity between SSG solutions,

and provide extensive analysis on the sensitivity of the model to changes in input.

Our analysis suggests that small changes in target values typically provoke small to

moderate changes in solutions. However, we found that a small change in the number

of available resources leads to a much larger changes in solutions. These results suggest

that exam creation is a difficult and sometimes counter-intuitive problem, and that

SSGs offer a fairly robust framework for providing solutions.

Induced Curriculum Problem

In Chapter 3, we pose the Induced Curriculum Problem (ICP). While we take the viewpoint

of the examiner in formulating the ESG, we switch our perspective to that of the teacher

in formulating the ICP. In short, this problem embodies a scenario where a teacher is

attempting to optimally teach to the test. In finding this optimal teacher strategy, we

intend to gain insight into how an exam’s subject matter influences class curricula.

Again, our model development is a major contribution within this chapter. The

challenge faced by teachers is a direct result of a limited amount of teaching time. Simply](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-15-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 13

of high-stakes testing may narrow their curriculum by teaching only a subset of the

possible topics, based on what they believe will be tested. Extensive previous research

has, in fact, indicated the presence of teaching to the test in US and UK schools [6, 9,

17–19]. In particular, teachers are able to take advantage of access to previous exams and

accurately make predictions about which questions will appear on future exams.

The predictability of assessments is not a fault of the exam creators, but rather a

consequence of the limited length of tests. Exam creators are faced with the challenge

of producing an exam which yields an accurate measure of student attainment with

often far fewer questions than topics. Additionally, exam creators must take into account

the varying importance of each topic. As the number of topics increases, the shear

scale of the problem makes producing near-optimal exams very difficult for humans. In

an effort to provide a solution to this challenge and develop tests which minimise the

consequences of teachers narrowing curriculum, we introduce the Examination Security

Game (ESG) as an instance of a Stackelberg Security Game (SSG).

Within recent years, SSGs have established themselves as an effective framework for

developing optimised security strategies against a broad spectrum of physical security

threats. Since 2009, SSGs have been studied and implemented in settings including but

not limited to: (i) in-flight and airport security [4, 15]; (ii) for the US Coast Guard

across a number of select ports nationwide [5]; (iii) environmental protection [20]; (iv)

conservation efforts against poaching and illegal fishing [12]; and (v) urban security

in transit systems [14]. In each scenario, SSGs are used as a framework to generate

an optimal security schedule which randomly distributes a limited number of security

resources amongst a set of targets. The undoubtedly impressive track record of success

supports the use of SSGs to the challenge faced by exam boards in creating unpredictable

tests which cover a full gamut of topics with a limited number of questions.

In this chapter:

1. We model the interaction between examiners and teachers as a Stackelberg Security

Game. We demonstrate that the assumptions necessary for the SSG also hold

within our model. By leveraging the SSG framework, we aim to create exams which](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-19-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 14

optimally use a limited number of questions to minimise the losses from teaching to

the test.

2. We implement a recently developed algorithm which uses mixed-integer linear

programming (MILP) to solve the optimisation problem faced in SSGs. We develop

an implementation in Mathematica for the purposes of experimentation, and develop

an implementation in the more popular JavaScript to serve as the first publicly

available solver for SSGs.

3. We perform a number of experiments to characterise the runtime of our solver

and introduce a novel approach for characterising the effect of uncertainty on the

outcome of SSGs.

Please note that we assume a basic knowledge of game theory. For a comprehensive guide

to the subject, please consider consulting the excellent text by Maschler et al. [21].

2.2 Stackelberg Security Games: A Case Study

To introduce Stackelberg Security Games, we present a setting where SSGs have been

successfully applied to generate security schedules for guarding against in-flight security

threats [4]. With this example, we aim to provide intuition to the format of SSGs before pre-

senting a formal description, and finally casting the problem of optimally randomising ex-

ams as an SSG.

In our case study, we consider the problem of deploying a limited number of air marshals

across commercial flights to protect against hijacking and other malicious attacks. There

are an estimated 30,000 flights in the United States every day, yet the Federal Air Marshal

Service (FAMS) has only an estimated 4,000 employed air marshals. To add to the

challenge, on any given day, only a portion of these air marshals are available for work [22].

In this scenario, FAMS must produce a security schedule, which allocates their limited

resources (air marshals) across the possible targets (flights). Furthermore, they must do so

under the assumption that potential attackers can employ surveillance tactics to monitor

previous security schedules before attacking. Certainly in this scenario, a deterministic

security schedule would present a security vulnerability, as a hijacker could simply attack](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-20-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 15

a flight which would be unprotected according to the deterministic schedule. To combat

this, FAMS must introduce an element of randomness into the security schedule.

Taking nothing else into account, FAMS could present a security schedule which placed

air marshals across flights uniformly at random. Such a strategy would eliminate any

advantage an attacker could gain from performing surveillance, yet doing so would fail

to take into account the varying threat levels across different flights. Certainly, a flight

from Cincinnati to Albuquerque faces less of a threat than a flight from New York City

to Washington, DC. Intuitively, then, an air marshal should be present on the flight from

New York to Washington, DC with higher probability than the flight from Cincinnati

to Albuquerque. How, then, should FAMS create a schedule which is randomised, and

therefore unpredictable, but still takes into account varying threats?

2.2.1 Characteristics of SSGs

To solve the problem faced by FAMS, Milind Tambe et al. model the interaction as a

Stackelberg Security Game [4]. SSGs exhibit several key characteristics, which we will

briefly motivate here before providing formal definitions in Section 2.3.

Limited Resources to Protect Targets At their core, Stackelberg Security Games

model a scenario where a defender with limited resources is attempting to protect a set

of targets which face the threat of attack from an adversary. To do so, the defender

must commit to a security schedule, which represents a valid allocation of the available

resources across targets. In the above flight security example, an example of a valid

security schedule for a given day may entail deploying each available air marshal to

two flights. In this particular example, the schedule may also account for the current

location of air marshals as well as pairing flights based on the same arrival/departure

airport. Importantly, we make the assumption that a security schedule which covers all

targets is not feasible, thus creating a complex problem for security teams.

Leader-Follower Structure Critically, Stackelberg games are two-player games which

exhibit a leader-follower structure. This is an assumption of information asymmetry which

is based on the follower knowing the strategy of the leader. Specifically within the context](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-21-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 16

NYC to Washington, DC Cincinnati to Albuquerque

Covered Uncovered Covered Uncovered

Defender Utility 5 -8 1 -2

Attacker Utility -8 9 -2 3

Table 2.1: Example utility values of an SSG

of SSGs, the leader is the defender, who first plays their strategy in the form of a security

schedule. The follower is the attacker, who plays an optimal response to the defender’s strat-

egy.

Covered v. Uncovered Targets SSGs account for two possible outcomes in the event

of an attack on a target. If the attacked target is uncovered (that is, if no defender

resource is deployed to the target at the time of attack), the attack is successful. This

results in a positive outcome for the attacker and a negative outcome for the defender.

If the attacked target is covered (that is, if a defender resource is deployed to the

target at the time of attack), the attack is unsuccessful. This results in a negative

outcome for the attacker and a positive outcome for the defender.

Variable Target Values As exhibited in the setting of deploying air marshals across

flights, the targets in SSGs face variable threats as a result of different risk/reward

payoffs to the attacker. The flight from New York to Washington, DC faces a higher

threat because hijacking this flight would provide more value to the attacker. In an SSG,

this value is captured by associating each target with a utility for the attacker in the

event of a successful or unsuccessful attack. These utilities vary from target to target,

embodying the risk/reward scenario faced by attackers. Likewise, for each target, the

defender receives utility payoffs which represent the loss or gain of a successful or thwarted

attack on that target. To illustrate this notion, Table 2.1 presents sample utility values

for flights from NYC to Washington, DC and from Cincinnati to Albuquerque.

The challenge of allocating scarce resources across many targets is not unique to

aircraft security. The above security problem has been studied within the context of port

protection [5], wildlife conservation [12], and airport security [11, 15]. Computational

game theory offers a framework for modeling these problems and the computational](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-22-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 17

engine for creating a randomised security schedule which maximises the capabilities of

a limited set of resources. In the following section, we formally present SSGs.

2.2.2 Stackelberg Security Games

With some intuition to the model and purpose of SSGs, we now more make a more formal

presentation, adapting notation found throughout the literature [4, 16, 23, 24].

Definitions and Notations

A Stackelberg Security Game, coined originally by Kiekintveld et al. in 2009 [16], is a

two-player game between a defender, D, and an attacker, A. The defender is tasked

with protecting a target set of size n using a resource set of size m. The target set is

denoted T = {t1, t2, . . . , tn}, and the resource set is denoted R = {r1, r2, . . . , rm}.

A set of schedules is denoted as S ∈ 2T , where each schedule s ∈ S represents a

set of targets that can be simultaneously defended by one resource. An assignment

function A : R → 2S, indicates the set of schedules which can be defended by each

resource. That is, ri can cover any schedule s ∈ A(ri) [16, 23].

The attacker’s pure strategy space, denoted by A, is the set of targets. A mixed strategy

for the attacker over these pure strategies is represented by a vector a = a1, a2, . . . , an ,

where each ai denotes the probability of attacking target ti.

The defender’s pure strategy space, denoted by D, is the set of feasible assignments

of resources to schedules. That is, each resource ri is assigned to a schedule si ∈ A(ri).

Critically, SSGs make the assumption that covering a target with one resource provides

the same protection as covering it with multiple targets. The defender’s pure strategy

can be represented by a coverage vector d = d1, d2, . . . , dn . Each component di ∈ {0, 1}

denotes the whether target ti is covered (di = 1) or uncovered (di = 0). A mixed strategy

for the defender, C, is a vector which specifies the probabilities of playing each d ∈ D.

Cd

denotes the probability of deploying the feasible coverage vector d. Additionally, let

c = c1, c2, . . . , cn be the vector of coverage probabilities corresponding to C such that each

component ci = d∈D

diCd

, a sum representing the marginal probability of covering ti [23].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-23-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 18

Utilities

As expressed in Table 2.1, the payoffs to each player in the event of an attack depend

only on whether or not the attacked target was covered by some defender resource. This

critical feature allows us to sufficiently define payoffs over an entire SSG by defining

four payoffs for each target: a utility for the defender and for the attacker in the event

target ti was attacked in the cases that it was covered or uncovered.

• Uu

A(ti) denotes the attacker’s utility for attacking target ti when it is uncovered.

That is, when no defense resource is allocated to ti.

• Uc

A(ti) denotes the attacker’s utility for attacking target ti when it is covered. That

is, when there is some defense resource allocated to ti.

• Uu

D(ti) denotes the defender’s utility in the event of an attack on target ti when it

is uncovered.

• Uc

D(ti) denotes the defender’s utility in the event of an attack on target ti when it

is covered.

Expected Utility

The expected utility for both players is dependent upon these utilities and the strategy

profile C, a . For a given defender strategy C, we denote the attacker’s expected

utility from attacking ti as UA(C, ti). Recalling that ci, calculated from C, denotes the

probability that the defender allocates a resource to cover ti, it follows that:

UA(C, ti) = ci · Uc

A(ti) + (1 − ci) · Uu

A(ti)

[25]

Summing over all targets weighted by the probability of an attack on each, as indicated

by the attacker’s mixed strategy a, we conclude that the expected attacker utility, under

strategy profile C, a , is:

UA(C, a) =

n

i=1

ai · UA(C, ti)

=

n

i=1

ai (ci · Uc

A(ti) + (1 − ci) · Uu

A(ti))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-24-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 19

Likewise, we find the expected utility for the defender under strategy profile C, a :

UD(C, a) =

n

i=1

ai (ci · Uc

D(ti) + (1 − ci) · Uu

D(ti))

Strong Stackelberg Equilibrium

The solution concept which we are interested in is referred to as a Strong Stackelberg

Equilibrium (SSE). In short, this solution concept satisfies the property that the defender

will choose an optimal mixed strategy over their pure strategies based on the assumption

that the attacker will choose their optimal response to this defender strategy [16]. The

strong form of this equilibrium further assumes that, in the event the attacker has multiple

optimal responses, she will break the tie by choosing the response which yields maximum

expected utility for the leader. This assumption is justified due to the fact that, in the event

of a tie, the defender can prompt the SSE by playing a mixed strategy which is arbitrarily

close to the equilibrium, provoking the attacker to play the desired response [24]. Critically,

this assumption guarantees the existence of an optimal mixed strategy for the leader [26].

To formally define the requirements for an SSE, we first define the attacker’s response

function R(C), which maps a defender strategy to a set of optimal attacker responses to

that defender strategy. Additionally, we define r : C → R which maps a defender strategy

to the expected utility of an optimal attacker response. That is, r(C) = UA(C, x) where x ∈

R(C).

Definition 1. A strategy profile C, a forms a Strong Stackelberg Equilibrium if it

satisfies the following three conditions

1. The attacker plays an optimal response to the defender strategy:

UA(C, a) ≥ r(C)

2. The defender chooses an optimal mixed strategy based on the attacker’s response

function:

∀C , ∀y ∈ R(C ), ∃x ∈ R(C) s.t. UD(C, x) ≥ UD(C , y)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-25-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 20

3. The follower breaks ties optimally for the leader:

∀x ∈ R(C) U(C, a) ≥ UD(C, x))

[16, 23]

2.3 Examination Security Game: Developing the Model

Daniel Koretz, of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, provides a one-sentence

summary of a common problem of exams which we will be addressing:

The core of the problem is that the sampling from the target used in creating

most large-scale assessments is both sparse and predictable over time. [10]

In this section, we model the interaction between examiners and teachers1 as an Exami-

nation Security Game (ESG). ESGs are instances of SSGs which incorporate additional

assumptions to tailor the model to the setting. In particular, we will use ESGs to

investigate teaching to the test in the form of narrowing the curriculum, a strategy which

completely dismisses a topic, allocating no time to studying it. In the spirit of SSGs,

such behaviour will be referred to as attacking a topic. Optimally for a teacher, she

would predict exactly which topics will not be covered on the test and attack those

topics. To represent this notion within the context of ESGs, we reward a teacher with

a positive payoff when she can successfully predict a topic that will not appear on the

test. On the other hand, if a teacher attacks a topic which does appear on the test, she

will receive a negative payoff. Critically, the payoffs for the teacher are influenced by

the difficulty of the topic. If a teacher successfully attacks a more difficult topic, she

will save more time, and will accordingly receive a greater payoff in the ESG.

Meanwhile, an examiner aims to prevent teacher’s from successfully attacking topics.

If an examiner covers a topic which a teacher attacks, she receives a positive payoff. On the

other hand, if a teacher is attacks a topic which is not covered on the test, the examiner’s

1

Within ESGs, the term examiner refers to the person or group who determines what content will

appear on an exam. The term teacher refers to any person who decides how to allocate study time for a

student who will be taking the exam. By this definition, please keep in mind that the student may also

be her own teacher. For instance, this is the case for any self-initiated exam preparations, as well as in

self-taught and online courses.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-26-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 21

measure of student attainment is compromised, resulting in a negative payoff to the exam-

iner. Critically, the payoffs for the examiner are scaled based on the relative importance of

each topic.

Stackelberg Security Games make several key assumptions that formulate a realistic

model of physical security scenarios. In this section, we discuss the analogous assumptions

within a high-stakes testing setting, and demonstrate that the SSG model is fitting, in

some ways perhaps even more so than in its traditional security settings.

2.3.1 Fulfilling the Assumptions of SSGs

Leader-Follower Structure

As noted previously, SSGs exhibit a leader-follower model, an assumption of informational

asymmetry. Within traditional security settings, this assumption requires that an attacker

has the necessary means to obtain knowledge of the defender’s strategy, typically through

surveillance methods. In some security settings, such as air marshals defending against

hijacking, such surveillance would require extensive planning and substantial funding.

Within the context of test-taking, exam boards often make previous exams freely avail-

able [27–29]. Certainly, the necessary resources for obtaining knowledge of the examiner’s

testing strategy are marginal in comparison to most physical security settings. We conclude

that interaction between examiners and teachers fits very well into the leader-follower struc-

ture of Stackelberg games.

Limited Resources to Cover Many Topics

Within an SSG, a defender has a fixed number of resources that they can allocate to

cover targets. Analogously, within an ESG, we view each exam question as a resource

which the examiner allocates to topics according to their mixed strategy. The number

of exam questions is limited, meaning that not all possible topics can be covered on

an exam. Dr. Kimberly O’Malley, Pearson’s Senior Vice President for Research and

Development, has expressed the dilemma created by this setting:

Because we can’t test everything in a year (no one wants the test to be longer

than necessary), decisions must be made. [3]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-27-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 23

due to their physical location and scheduled work hours. These constraints, however,

become superfluous within the context of the Examination Security Game.

Specifically, we assume that each exam question can cover any one single topic.

That is, if there are three questions on an exam (denoted Q1, Q2, and Q3), and five

potential topics, we assume that Q1, Q2, and Q3 could all cover any one of the five topics.

As with SSGs, we also assume that each question covers a unique topic, as covering

a target with multiple resources provides no benefit for the defender if that target is

attacked. 2 Following the notation of SSGs, the set of schedules within an Examination

Security Game is simply the set S = {s1, s2, . . . , sn} where si = {ti}.

With this in mind, assuming all that all m questions on the exam are used, the

set of possible pure strategies for the defender is set n

m .

Notation of ESG

The notation of the ESG very closely follows the notation of the SSG. The two players are

again denoted D and A. Keep in mind that, within the context of the ESG, D denotes

the examiner, and A denotes the teacher. The examiner must “protect” a set of n topics

T = {t1, t2, . . . , tn}. To do so, she has m questions at her disposal. Please note that,

following the above discussion, we no longer refer to the notion of a resource set.

The teacher’s pure strategy space, denoted by A, is the set of topics. A mixed strategy for

the teacher, denoted by a, is a vector where each component, ai, represents the probability

of attacking topic ti.

As discussed, the examiner’s pure strategy space, denoted by D, is the set of vectors

d ∈ n

m . A mixed strategy for the examiner is represented by a vector C = c1, c2, . . . , cn

with cidenoting the probability of covering topic ci. C must meet the following constraints:

1. The probability of each topic being on the exam is between 0 and 1:

ci ∈ [0, 1] for i = {1, 2, . . . , n}

2. The sum of all probabilities is at most m:

2

Both within the context of exams and physical security settings (e.g. in-flight security), it can be

argued that allocating multiple resources to a target offers some additional benefit to the defender. This

assumption is further addressed in Chapter 3. Within the SSG model, however, a target is only considered

in a “covered” or “uncovered” state.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-29-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 25

Utilities in the ESG

For completeness, we denote the analogous player utilities within the context of the

ESG, and provide a summary of possible factors influencing their value.

• Uu

A(ti) denotes the teacher utility for attacking (i.e. not preparing for) exam target

ti when it is untested (uncovered)

• Uc

A(ti) denotes the teacher utility for attacking (i.e. not preparing for) exam target

ti when it is tested (covered)

• Uc

D(ti) denotes the examiner’s utility when the teacher attacks exam target ti and

it is tested (covered)

• Uu

D(ti) denotes the examiner’s utility when the teacher attacks exam target ti and

it is untested (uncovered)

Please note the expected utility functions for both players follow identically from those pre-

sented in Section 2.2.3.

2.3.3 Efficiently Finding Strong Stackelberg Equilibriums

In 2008, Kiekintveld et al. [16] introduced the ERASER (Efficient Randomised Allocation

of Security Resources) algorithm for efficiently finding SSEs of SSGs by casting the problem

as a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problem. ERASER leverages a concise rep-

resentation of a SSG which is realised through exploiting special characteristics of the game.

Concise Representation of SSGs

SSGs can be naively modeled with a normal-form representation which iterates over

all possible pure defender strategies. Given n targets and m resources, there are n

m

possible defender strategies, a value exponential in the number of topics. Because of this

exponential relation with respect to n, SSGs become unwieldy very quickly as the number

of targets grows if a normal-form representation is used. Table 2.2 presents an example

normal-form representation of pure strategies with n targets and m resources.

However, using the special features of SSGs, a compact representation has been

developed by Kiekintveld et al. [16], which we will use to efficiently find a solution to

ESGs. A critical characteristic of SSGs, and hence ESGs, is that player payoffs are](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-31-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 26

Pure Strategy Index Covered Targets Probability

1 1,2 d1

2 1,3 d2

3 1,4 d3

4 2,3 d4

5 2,4 d5

6 3,4 d6

Table 2.2: Exponentially large iteration of pure strategies

Supply and Demand Financial Markets Government Policy Foreign Exchange

Covered Uncovered Covered Uncovered Covered Uncovered Covered Uncovered

Examiner 6 -1 9 -9 2 -3 7 -10

Student -6 5 -10 3 -7 4 -2 4

Table 2.3: Concise representation of utility

only dependent on the target attacked and whether or not that target is covered by

the defender. That is, within the context of ESGs, if a teacher attacks topic ti, the

resulting payoffs for both the examiner and the teacher are only dependent on whether a

question covering topic ti is on the exam. The payoffs are unaffected by whether or not a

question covering some topic tj, with tj = ti, is present on the test. This feature of SSGs

creates an additional structure which can be exploited to create a concise representation.

Exploiting this feature, Kiekintveld et al. [16] developed a concise representation of SSGs,

which we demonstrate in Table 2.3, continuing with the previous example::

ERASER Algorithm

The ERASER algorithm takes advantage of the concise representation of SSGs and

finds an optimal defender strategy in the form of a coverage vector. The ERASER

algorithm casts the SSG optimisation problem as a mixed-integer linear program (MILP).

We provide the MILP optimisation problem in equations 2.1 to 2.7, as presented by

Kiekintveld et al. [16], with only changes in notation:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-32-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 27

max d (2.1)

at ∈ {0, 1} ∀t ∈ T (2.2)

t∈T

at = 1 (2.3)

ct ∈ [0, 1] ∀t ∈ T (2.4)

t∈T

ct ≤ m (2.5)

d − UD(C, t) ≤ (1 − at) · Z ∀t ∈ T (2.6)

0 ≤ k − UA(C, t) ≤ (1 − at) · Z ∀t ∈ T (2.7)

The objective of the MILP, as presented in equation 2.1, is to maximise d, which

represents the examiner’s (defender’s) utility. Equations 2.2 and 2.3 require that the

attacker attacks just a single target with probability 1. This constraint simplifies the

computational requirements of finding a solution, yet is without any loss in generality as an

SSE still exists with this constraint applied. Specifically, the constraint listed in Equation

2.2 should generally be met by simply requiring the constraint in equation 2.3. Recalling

that the contribution of a single target t to the expected attacker utility is defined as

UA(C, a) = n

i=1 ai (ci · Uc

A(ti) + (1 − ci) · Uu

A(ti)), with ci, Uc

A(ti), and Uu

A(ti) all fixed

for i ∈ {1, 2, . . . , n}, we denote vi = (ci · Uc

A(ti) + (1 − ci) · Uu

A(ti)), and rewrite the at-

tacker’s expected utility

UD(C, a) =

n

i=1

ai · vi

with vi ∈ R for i ∈ {1, 2, . . . , n}. Under the constraint of Equation 2.2, it follows that

the attacker can maximize her expected utility by setting ai = 1 for the corresponding

maximum vi, and all other aj = 0 for i = j. However, in the case that vi = vj for

some i, j such that i = j, it is possible that the attacker maximizes her expected utility

otherwise, such as setting ai = aj = 0.5, and ak = 0 for all k which are not i or j.

Equation 2.2 is therefore necessary for allowing for computational simplifications.

Equation 2.4 ensures that the coverage vector is valid, constraining each element to a

valid probability in the interval [0, 1]. Equation 2.5 limits the defender’s coverage vector by

the amount of resources available, m.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-33-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 28

As explained by Kiekintveld et al. [16], Equation 2.6 introduces Z, a constant which

is larger than the maximum payoff for either the attacker or defender. To be sure, our

implementation sets Z to the product of the number of targets, n, and the maximum

utility for either player across all targets. Referring to the right hand side of Equation

2.6, the expression (1 − at) · Z evaluates to 0 for the attacked target, where at = 1, and

to Z for all other targets, where at = 0. As such, this constraint places an upper bound

UD(C, t) on d for only the attacked target. For unattacked targets, where at = 0, the

right hand side is equal to Z, and thus arbitrarily large. Because the MILP maximises d,

for all optimal solutions d = UD(C, a), it follows that C is maximal for any given a [16].

Equation 2.7 introduces a variable k. The first part of the equation forces k to be at

least as large as the maximal defender payoff received for an attack on any target. To make

the effect of the second part of the constraint more apparent, we can rewrite Equation 2.7:

0 ≤ k − ct · Uc

D(t) + (1 − ct) · Uu

D(t) ≤ (1 − at) · Z

For any target which is not attacked, such that at = 0, the constraint becomes:

0 ≤ k − ct · Uc

D(t) + (1 − ct) · Uu

D(t) ≤ 0

It follows that k−ct ·Uc

D(t)+(1−ct)·Uu

D(t) = 0 for any unattacked target. If the attack

vector specifies a target which is not maximal, this constraint is violated. The resulting

effect of the constraints placed by equations 2.6 and 2.7 ensure that the coverage vector,

C, and the attacking vector, a, are mutual best-responses in any solution which maximises d

[16].

2.4 Implementation of the ERASER Algorithm

2.4.1 Converting ERASER MILP to a Table of Linear Expressions

The ERASER algorithm was implemented in both Mathematica and JavaScript. To

utilise pre-existing MILP solvers, we first reformatted equations 2.1 to 2.7, writing them

as linear expressions over our list of variables from the ERASER MILP:

• d

• k](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-34-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 30

d k c1 c2 . . . cn a1 a2 . . . an b

Eq. 2.2 for t1 0 0 0 0 . . . 0 1 0 . . . 0 ∈ {0, 1}

Eq.2.2 for t2 0 0 0 0 . . . 0 0 1 . . . 0 ∈ {0, 1}

. . . . . .

Eq.2.2 for tn 0 0 0 0 . . . 0 0 0 . . . 1 ∈ {0, 1}

Eq.2.3 0 0 0 0 . . . 0 1 1 . . . 1 = 1

Eq.2.4 for t1 0 0 1 0 . . . 0 0 0 . . . 0 ∈ [0, 1]

Eq.2.4 for t2 0 0 0 1 . . . 0 0 0 . . . 0 ∈ [0, 1]

. . . . . .

Eq.2.4 for tn 0 0 0 0 . . . 1 0 0 . . . 0 ∈ [0, 1]

Eq.2.5 0 0 1 1 . . . 1 0 0 . . . 0 ≤ m

Eq.2.6 for t1 1 0 −∆D(t1) 0 . . . 0 Z 0 . . . 0 ≤ Z + Uu

D(t1)

Eq.2.6 for t2 1 0 0 −∆D(t2) . . . 0 0 Z . . . 0 ≤ Z + Uu

D(t2)

. . . . . .

Eq.2.6 for tn 1 0 0 0 . . . −∆D(tn) 0 0 . . . Z ≤ Z + Uu

D(tn)

Eq. 2.7 for t1 0 1 −∆A(t1) 0 . . . 0 Z 0 . . . 0 ≤ Z + Uu

A(t1)

Eq. 2.7 for t2 0 1 0 −∆A(t2) . . . 0 0 Z . . . 0 ≤ Z + Uu

A(t2)

. . . . . .

Eq. 2.7 for tn 0 1 0 0 . . . −∆A(tn) 0 0 . . . Z ≤ Z + Uu

A(tn)

Eq. 2.7 for t1 0 1 −∆A(t1) 0 . . . 0 0 0 . . . 0 ≥ Uu

A(t1)

Eq. 2.7 for t2 0 1 0 −∆A(t2) . . . 0 0 0 . . . 0 ≥ Uu

A(t2)

. . . . . .

Eq. 2.7 for tn 0 1 0 0 . . . −∆A(tn) 0 0 0 ≥ Uu

A(tn)

Table 2.4: ERASER MILP represented as a table of linear expressions

Please note that constraints such as ci ∈ [0, 1] are handled by combining the

constraints ci ≤ 1 and ci ≥ 0. These were joined in the above table for brevity.

Likewise, constraints of the form ai ∈ {0, 1} are handled similarly, but also adding

the requirement that ai is an integer. In total, for an instance of ESG with n topics,

the corresponding MILP has 2n + 2 variables and 7n + 2 constraints.

2.4.2 Solving ERASER MILP

The ERASER algorithm casts the problem of finding a SSE to a MILP, taking advantage of

pre-existing MILP solvers to efficiently find a solution. In particular, the simplex method

and interior point methods are often used in practice for linear optimisation problems.

Simplex and revised simplex methods, while having a worst-case runtime exponential in

the number of constraints, and therefore in n in our case, typically perform much better

than worst case in practice. In fact, analysis by Spielman and Teng [30] demonstrates that

the simplex algorithm usually runs in polynomial time in the number of variables and

constraints. Furthermore, randomised simplex algorithms have been introduced which run

in worst-case polynomial time in the number of variables and constraints [31]. Interior point](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-36-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 31

methods, on the other hand, allow for very fast machine-precision approximations, and

are an excellent option for large-scale MILPs [32]. Due to the relative uncertainty in these

methods, we provide runtime analysis on randomly generated instances of SSGs below.

JavaScript Implementation

Following the previous discussion, an implementation of ERASER coded in JavaScript was

developed as the first publicly available solver for SSGs. To solve the MILP, we leveraged

an open source JavaScript simplex algorithm [33]. The full code can be found in Appendix

A, and is also available at https://github.com/rcmoore38/stackelbergsecuritygamesolver.

Mathematica Implementation

A Mathematica implementation of ERASER was used to run experiments whose results are

found in the following section. This implementation takes advantage of Mathematica’s col-

lection of algorithms for solving linear optimisation problems. The full code can be found in

Appendix B.

2.4.3 Results

The following experiments were conducted on a 2.6 GHz Intel Core i5 3337U processor

with access to 8GB of RAM. All experiments were done running Mathematica 10.0,

using the built in function to solve the MILPs. This function uses a combination

of the revised simplex method and interior point methods.

Runtime Analysis

In the first set of experiments, we analyse the runtime of our algorithm on randomly

generated instances of ESGs, varying the number of topics and the number of exam

questions. For each instance, we randomly generate utility values, drawing indepen-

dently and uniformly at random from the following intervals:

• Uc

D(t) : [0, 10] ∀t ∈ T

• Uu

D(t) : [−10, 0] ∀t ∈ T

• Uc

A(t) : [−10, 0] ∀t ∈ T

• Uu

A(t) : [0, 10] ∀t ∈ T](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-37-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 34

Figure 2.2: Uncertainty and coverage Similarity

between the potential size of error in the input and the change in the suboptimal

coverage vector. We now present this method explicitly.

First, we generate utility values for 5 targets, chosen independently and uniformly

at random from the standard experimentation utility intervals.

Using our implementation of the ERASER algorithm, we find an optimal mixed strategy

for the examiner based on these drawn utilities, assuming that there are 2 available exam

questions (m = 2). We represent this mixed strategy by the coverage vector c, where each

component ci indicates the marginal probability that topic ti is covered on the exam.

Next, for each target t, we draw two values uniformly at random from the interval

[−u, +u]. Denote these values as u1 and u2. Please note that we refer to an assumption

of 20% as an experiment trial with u1, u2 randomly drawn from the interval [−.2, .2].

This notation is inspired by the possibility that original utility values could have an error

of up to 20%. We scale the attacker utility values in the following fashion:

• Uc

A(t) = Uc

A(t) · u1 ∀t ∈ T

• Uu

A(t) = Uu

A(t) · u2 ∀t ∈ T

We once again use our implementation of the ERASER algorithm to find an optimal cover-

age vector c† for the modified inputs. Using cosine similarity, we compare the two coverage

vectors:

Sc(c, c†) =

c · c†

||c|| · ||c†||](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-40-2048.jpg)

![2. Examination Security Game 36

Figure 2.3: Effect of the number of questions on coverage similarity

the cosine similarity between the coverage vector with 1 available question and the coverage

vector with n available questions. A smoothed distribution over 5000 trials is shown.

Reasonably, one may expect a high degree of similarity between all four coverage

vectors. That is, it seems reasonable that an ideal coverage vector when two questions

are available is very similar to the coverage vector when one question is available, just

scaled by a factor of two. Interestingly, this behaviour was not evidenced by the results.

In general, changing the number of questions available prompted a much greater effect

on the coverage vector than modifying the attacker utilities by 40%. This surprising

result indicates a great need to take a closer look at exam creation. Certainly, however,

such counter-intuitive results are difficult to factor in by a human examiner. Indeed, this

motivates further analysis of teaching to the test with Stackelberg Security Games.

2.5 Summary

There is no doubt that examiners face a remarkably difficult challenge in creating

unpredictable exams which tests students across many topics. In this chapter, we

cast this challenge as a Stackelberg Security Game, taking advantage of this powerful

framework to create exam strategies which minimise the effect of teaching to the test.

To do this, we created a model of the interaction between an examiner and a teacher,

and demonstrated that the same assumptions made by SSGs to fit traditional security

settings also hold within this context. We then implemented the ERASER algorithm

[4], which takes advantage of a concise representation of the game to cast it as a MILP.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-42-2048.jpg)

![3. Induced Curriculum Problem 44

before solving more difficult tier 2 additions. To handle this, in the following section

we introduce proficiency functions and scoring functions.

3.4 Proficiency, Scoring, and Valuation

Topic proficiency is a measure of capability of a student. It gives a ranking to questions,

according to difficulty, and allows us to decide which topic questions a student can and can-

not successfully answer. Given a topic t, if a student has proficiency αt in topic t, she will

be able to answer a question on topic t if and only if that question requires proficiency ≤ αt.

Formally,

Definition 2. An exam question is a pair (t, αt), where t denotes the topic and αt ∈ [0, 1]

denotes the required level of proficiency in t to provide a correct solution.

Borrowing from the Utility Representation Theorem [34], within a topic, we require

exam questions to satisfy the following relationships, given any questions q1 = (t1, α1), q2 =

(t2, α2), q3 = (t3, α3):

1. Completeness: Either α1 ≤ α2 or α2 ≤ α1. Or both, in which case q1 can be

answered correctly by a student if and only if q2 can be answered correctly.

2. Transitivitiy: If α1 ≤ α2 and α2 ≤ α3, then α1 ≤ α3

For all exam questions within a topic, we assume these relationships are satisfied and

can thus create an ordering of questions (q1, q2, . . . , qk) such that a student being able to

answer question qi implies she is sufficiently proficient in the topic to answer questions

q1, q2, . . . , qi−1 as well [34]. As such, we can assign a student a proficiency α such

that αi ≤ α ≤ αi+1. With this value, we have all the necessary information for

determining which questions a student can and cannot answer.

For simplicity, we require that all proficiencies are rated on the interval [0, 1], where a

proficiency of 0 implies a student can answer no questions on the topic and a proficiency

of 1 implies a student can answer any question on the topic. We formulate the notion

of proficiency as above in order to avoid making any assumptions of exact measures

of student abilities. For instance, it is reasonable to give a ranking to questions

in terms of difficulty, but defining each one on an interval [0, 1] is an unreasonable](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-50-2048.jpg)

![3. Induced Curriculum Problem 45

assumption. Instead, proficiency is a ranking, similar to the notion of utility in the

study of economics, which we simply constrain to the interval [0, 1].

The notion of proficiency allows us to formally define scoring functions and profi-

ciency functions. Scoring functions, similarly to the sample scoring relation in Table

3.2, give a mapping from proficiency in a topic to a score. Proficiency functions,

in the spirit of the sample proficiency relation in Table 3.3, give a mapping from

time spent learning a topic to proficiency in that topic.

Definition 3. Given a topic t and a student who has proficiency αt ∈ [0, 1] in t, a scoring

function for t is a monotonic increasing function gt : [0, 1] → R≥0 which gives a score

gt(αt).

Within the greater context of teaching to the test, the scoring functions embody

what an instructor believes will be covered on the exam. While we do not make any

assumptions as to how exactly these functions are defined, we note that a teacher can

define scoring functions based on previous exams, as shown in our example. However, it

is also plausible that a teacher forms scoring functions based on a hunch, newly reviewed

education standards, or some other independent source of information.

We make no assumptions regarding the form of scoring functions, besides their

monotonicity. We do, however, bring particular attention to the importance of step

functions within the context of the ICP. Exams which assess student proficiency based on

a set of questions at fixed proficiency levels are characterized by scoring functions which

are step functions. That is, a student’s score is only increased if her proficiency passes

some threshold. Proficiency functions of this form will be discussed in detail in Section 3.7.

We now introduce proficiency functions.

Definition 4. Given a topic t, a proficiency function for t is a monotonic increasing

function Lt : R≥0 → [0, 1] which gives a mapping from the amount of time (in hours) a

student is taught that topic, denoted at, to the level of proficiency in that topic, denoted

αt, such that the student can answer an exam question (t, α) if and only if αt ≥ α.

In every instance of the ICP, we make the critical assumption that a teacher has a

limited amount of class time which must be optimally allocated. However, depending](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-51-2048.jpg)

![3. Induced Curriculum Problem 49

Proof. We first remark that the ICP constraint t∈T at ≤ Z is met. By the capacity

constraint on the CKSP, we know that n

i=1 cti · xi ≤ Z :

Z ≥

n

i=1

cti · xi

=

n

i=1

ati

=

t∈T

at

We also note that each ati ≥ 0, resulting from xi ∈ [0, 1] and cti > 0 with ati = xi · cti .

We demonstrate that A is a maximal solution in a proof by contradiction by assuming

that there is some valid allocation B which yields a more optimal solution to the ICP. We

then show that, if this was the case, there would then exist a more optimal solution to the

corresponding knapsack problem. Formally, we claim that there is some valid allocation

B = {bt1 , bt2 , . . . , btn } such that:

n

i=0

Vti (bti ) >

n

i=0

Vti (ati )

n

i=1

bti ≤ Z

bti ≥ 0 for i = 1, 2, . . . , n

From B, we construct a more optimal solution to the corresponding CSKP, denoted

with Y . We define a mapping from each element bi to element yi ∈ Y :

yi = min{bti /cti , 1}

Note that Vti (bti ) = vti · cti · yi. To see this, we break into two cases: (i) If bti ≥ cti ,

then yi = 1 and Vti (bti ) = vti · cti , as defined by Vti , and we are done, as . (ii) If bti < cti ,

then yi = bti /cti and Vti (bti ) = vti · bti = vti · cti · yi

Now, using our assumption that B yields a more optimal solution to the ICP, we show

that k(Y ) > k(X):](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-55-2048.jpg)

![3. Induced Curriculum Problem 50

k(Y ) =

n

i=1

vti · cti · yi

=

n

i=1

Vti (bti ) (as shown above)

>

n

i=1

Vti (ati ) (by assumption)

=

n

i=1

vti · ati (by ati ≤ cti as xi ≤ 1)

=

n

i=1

vti · cti · xi

= k(X)

It remains only to show that Y meets the constraints of the CKSP. First, we claim

that each yi ∈ [0, 1]. This follows from our definition of yi = min{bti /cti , 1}, with cti > 0

by assumption and bti ≥ 0 by the ICP constraints.

Finally, we claim that Y satisfies the capacity constraint of the knapsack problem:

Z ≥

n

i=1

bti (by assumption)

≥

n

i=1

cti · yi

We conclude that Y meets the constraints of the knapsack problem and k(Y ) > k(X).

This contradicts our assumption that X is a solution to the knapsack problem.

3.5.3 Algorithmic Complexity

The CKSP can be solved in polynomial time with a greedy algorithm. In words,

the algorithm orders the items by their ratio of value to weight and fills the knap-

sack in order of decreasing value density until the bag is full [35]. Given n items,

this algorithm requires O(n log n) time to sort the items, and O(n) time to fill the

knapsack using the sorted list. The total runtime is thus O(n log n) time for this

greedy algorithm. In fact, however, the CKSP can be solved in O(n) time by ap-

plying a variation of the Weighted Median Problem [36].

Within the context of the ICP, each topic corresponds to exactly one item in the

CKSP. Casting an instance of the ICP over n topics with linear valuation functions to an](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-56-2048.jpg)

![3. Induced Curriculum Problem 54

ICP:

Z ≥

n

i=1

bti (by assumption)

≥

n

i=1

b∗

ti

(by definition)

=

n

i=1

a†

ti

· yi

Finally, we show that k(Y ) > k(X):

k(Y ) =

n

i=1

vti · yi

=

n

i=1

vti · (b∗

ti

/a†

ti

)

=

n

i=0

Vti (b∗

ti

)

=

n

i=0

Vti (fti (bti ))

=

n

i=0

Vti (bti )

>

n

i=0

Vti (ati ) by assumption

=

n

i=1

vti · xi (by xi ∈ {0, 1})

= k(X)

Thus, Y meets the constraints of the knapsack problem and k(Y ) > k(X). This

contradicts our assumption that X is a solution to the knapsack problem.

3.6.3 Algorithmic Complexity

The 0-1 KSP is a well-known NP-hard problem. While fully-polynomial approximation

schemes do exist [35], their analysis focuses on the closeness to optimality with respect to

total knapsack value. The ICP, however, has been designed with the intention of finding

an optimal allocation of teaching time, thereby providing a means to measure the effect

of high-stakes testing on curriculum deformation. As a result, we will focus on exact

algorithms. Fortunately, pseudopolynomial algorithms have been developed for finding

exact solutions. Given an upper bound on the value of the optimum solution, denoted

B, a dynamic programming algorithm can solve the 0-1 KSP in O(nB) time [37].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-60-2048.jpg)

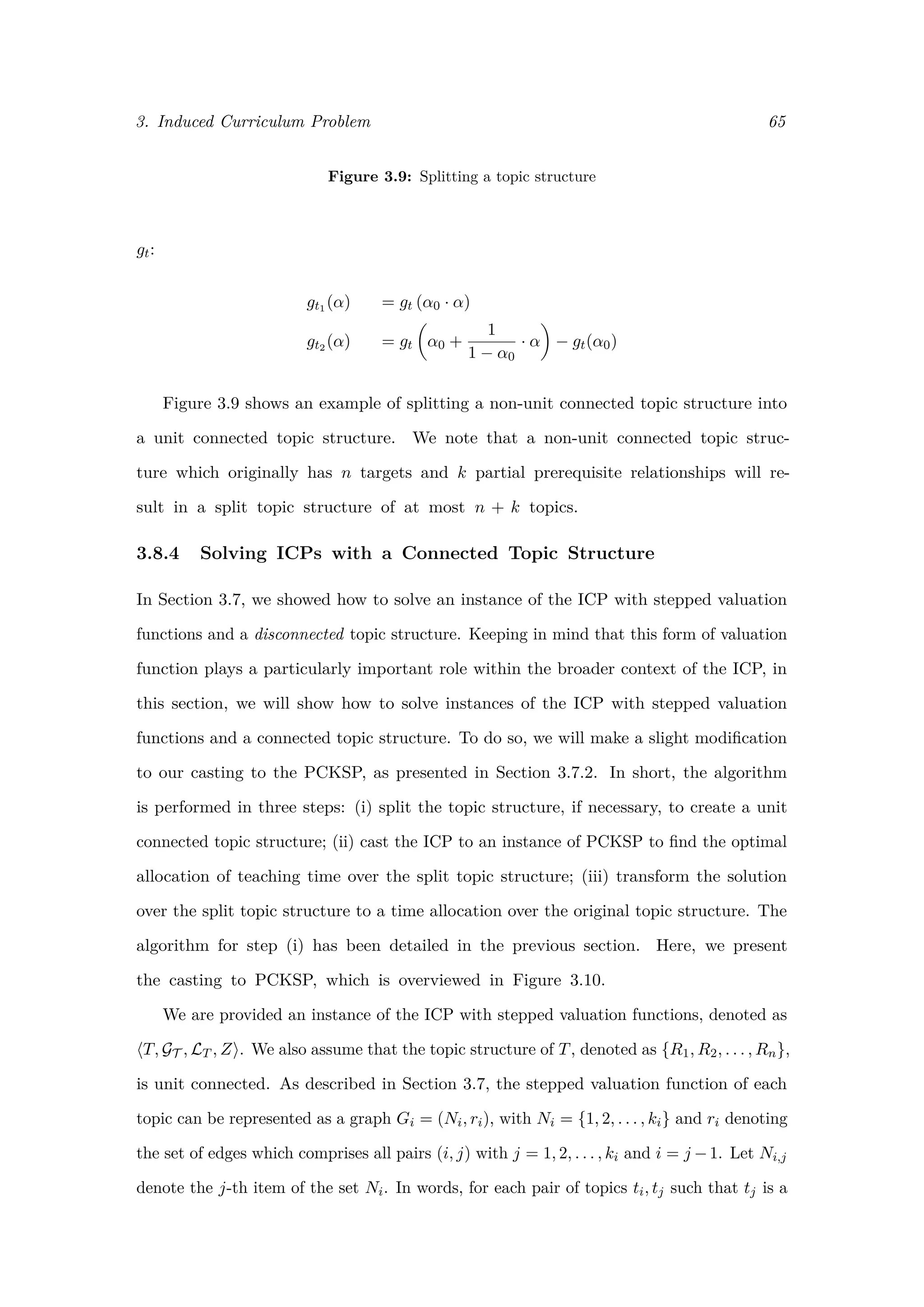

![3. Induced Curriculum Problem 56

Figure 3.6: Formation of stepped valuation functions with stepped scoring

Another important scenario to consider is when the scoring functions are step functions,

as shown in Figure 3.6. This is the case when an exam assesses students at one or more

fixed levels of proficiency. Consider, for instance, if an exam board releases tests with

questions that assess the same level of proficiency, but reword the question or change values

to make sure students cannot memorise answers from previous exams. In this case, step

functions capture the relationship between student proficiency and exam score very well.

Before we present an algorithm for finding solutions to instances of the ICP with

stepped valuation functions, we introduce the precedence constrained knapsack problem.

3.7.1 Precedence Constrained Knapsack Problem

The precedence constrained knapsack problem (PCKSP), also known as the partially

ordered knapsack problem, is a generalised version of the 0-1 knapsack problem which takes

into account precedence requirements between items. That is, given a set of items N, a

precedence relation exists between two items (i, j) ∈ N × N if and only if the item i can

be placed in the knapsack only on the condition that item j is also placed in the knapsack

[38]. We denote the set of these precedence relations as R, and represent the PCKSP as

a graph G = (N, R). As with the 0-1 KSP, each item has a value vi and a weight wi,

with the value xi ∈ {0, 1} indicating whether item i is included in the knapsack (with

xi = 1 indicating item i is in the knapsack). We must fill the knapsack to maximise total

value while meeting precedence constraints and a total capacity constraint C. Formally,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-62-2048.jpg)

![3. Induced Curriculum Problem 60

We denote the set of yi,j as Y , and use the assumed existence of Y to contradict that

X is a solution to the PCKSP.

We have already remarked that Y meets the precedence constraints and that each

yi,j ∈ {0, 1}, both following from Fact 1. Next, we claim that Y satisfies the capacity

constraint of the PCKSP. This follows from our assumption that D meets the capacity

constraint of the ICP:

Z ≥

n

i=1

dti (by assumption)

=

n

i=1 j∈Ni

wi,j · yi,j (by definition)

Finally, we see that k(Y ) > k(X) :

k(Y ) =

n

i=1 j∈Ni

vi,j · yi,j

=

n

i=1

Vti (dti )

>

n

i=1

Vti (ati ) (by assumption)

=

n

i=1 j∈N

vi,j · xi,j

= k(X)

Thus, Y meets the constraints of the PCKSP and k(Y ) > k(X). This contradicts our

assumption that X is a solution to the PCKSP.

3.7.3 Algorithmic Complexity

As demonstrated by Johnson and Niemi, the PCKSP is a strongly NP-complete problem

[39]. As such, current algorithms to solve instances of the PCKSP rely on enumeration

methods, such as branch-and-bound [40]. However, pseduopolynomial time algorithms

exist for solving the PCKSP in the case of prerequisite structures which are trees.

This is, in fact, the case in our formulation of the PCKSP if we simply add a dummy

vertex (of value and weight 0) which is connected to the first vertex in each set Ni for

i ∈ {1, 2, . . . , n}. While the tree-version of the PCKSP is still NP-complete [39], dynamic

programming solutions offer improvements on enumeration methods. We do however,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0d9e77d0-81ae-4105-9722-71426476b89e-170125034209/75/ExamsGamesAndKnapsacks_RobMooreOxfordThesis-66-2048.jpg)

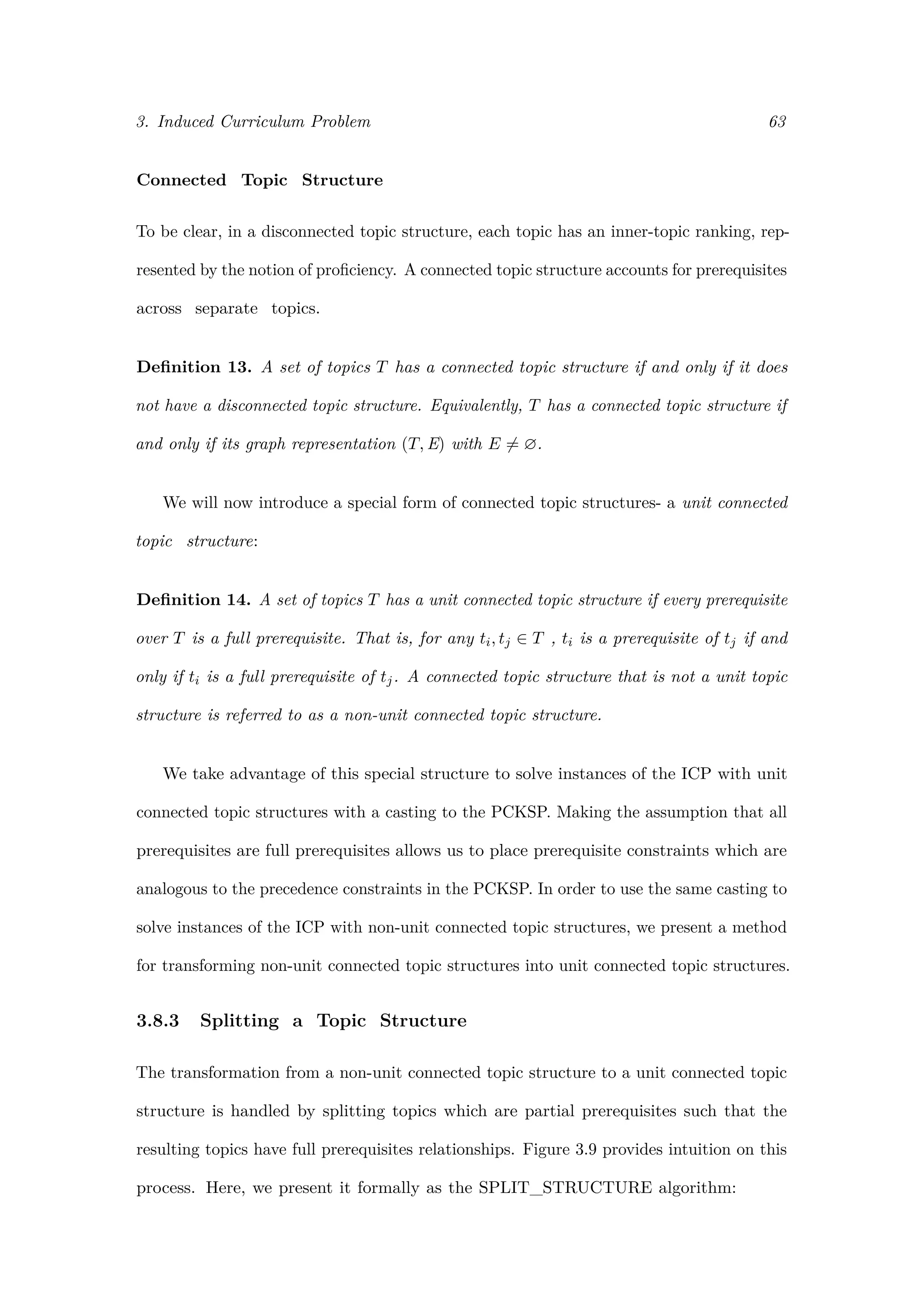

![3. Induced Curriculum Problem 61

make a warning regarding the size of the PCKSP which is dependent on the number

of steps in each valuation function, rather than just the number of topics.

3.8 Prerequisites and Topic Structures

3.8.1 Prerequisites

In our analysis from Section 3.5 through Section 3.7, we made the assumption that topics

were entirely independent of one another. That is, we assumed that proficiency in one

topic was never a requirement to acquiring proficiency in another topic. In this section, we

define prerequisites within the context of the ICP, and formally introduce topic structures.

Definition 7. A proficiency prerequisite to learning topic t0 is a pair (t, α), where

α ∈ [0, 1] is the proficiency in topic t required before acquiring any proficiency in topic t0.

Definition 8. A prerequisite proficiency function for topic t0, denoted as Rt0 , maps

each topic t with t = t0 to the proficiency required in t before acquiring proficiency in t0.

Denoting αt0,t as the proficiency in t necessary before acquiring any proficiency in t0, we

define Rt0 (t) = αt0,t.

Definition 9. A topic t is a prerequisite to topic t0 if Rt0 (t) > 0. If having proficiency

in topic t0 αt0 > 0 implies that any question (t, αt) can be succesfully answered, we refer

to t as a full prerequisite of t0. Otherwise, we refer to t as a partial prerequisite of t0.

Please note that this slightly verbose notion of a full prerequisite is a result of

our definition of proficiency, which corresponds to a ranking of questions according to

difficulty. In words, if t is a full prerequisite of t0, it simply implies that a student