Esl Readers And Writers In Higher Education Understanding Challenges Providing Support Norman W Evans

Esl Readers And Writers In Higher Education Understanding Challenges Providing Support Norman W Evans

Esl Readers And Writers In Higher Education Understanding Challenges Providing Support Norman W Evans

![1

UNDERSTANDING CHALLENGES,

PROVIDING SUPPORT

ESL Readers and Writers in Higher Education

Norman W. Evans and Maureen Snow Andrade

Vignette

A small but rapidly growing U.S.-based company is expanding into various Asian coun-

tries. They are seeking new employees who have three essential qualifications: solid aca-

demic training from a reputable business school, native proficiency in an Asian language,

and very strong English skills—particularly in speaking and writing. Since “native profi-

ciency” in an Asian language is required, a number of promising applicants are citizens of

Asian countries who studied business abroad in the United States. To determine the quality

of the applicants’ English skills, the committee has face-to-face interviews with applicants

and asks them to respond in writing to a memo that outlines a proposed business plan. The

search committee soon discovers that these applicants’ English skills, especially in writing,

are not at all what they expected from people who have spent years in the United States

studying at accredited universities. In some cases, the low level of English is disturbing.

Introduction and Overview of the Challenges

Students for whom English is a second language (ESL) not only benefit individ-

ually from higher education but contribute globally to the human condition and

public good.

There is a wealth of evidence that increased [educational] attainment

improves health, lowers crime rates, and yields citizens who are both glo-

bally aware and participate more in civic and democratic processes such as

voting and volunteering, all of which have enormous implications for our

democracy.

Lumina Foundation, 2013, p. 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/17206790-250523115445-076e5bdb/75/Esl-Readers-And-Writers-In-Higher-Education-Understanding-Challenges-Providing-Support-Norman-W-Evans-22-2048.jpg)

![Understanding Challenges, Providing Support 5

the United States on a short-term basis, while others—often referred to as Gen-

eration 1.5—are residents who arrived as children (early arrivals) or in their

preteen or teenage years (late arrivals) (Ferris, 2009; Kanno & Harklau, 2012).

Though international students must generally pass an English proficiency exam

to be admitted, they face significant cultural and linguistic challenges for which

their developing language skills may be inadequate (Andrade & Evans, 2009;

Ferris, 2009). Resident students also enroll with varying levels of English lan-

guage proficiency, often insufficient for the linguistic rigors of postsecondary

education (Ferris, 2009), yet these students are not typically required to establish

their level of English language proficiency prior to admission or even declare

themselves as NNESs.

The TOEFL and similar exams, required for international NNESs, are

designed to be a minimal indicator of the linguistic skill necessary for academic

success. These “institutional English language entry requirements can assist but

do not ensure that students will enter university at a sufficiently high level of

proficiency” (Barrett-Lennard, Dunworth, & Harris, 2011, p. 100). Resident

NNESs’ linguistic skills may be similar to or even weaker than those of inter-

national students, yet institutions may not assess these students. In some cases,

post-admission basic skills screening occurs. Even then, however, these students

may be directed to remedial reading and writing courses that do not address

their linguistic needs. Additionally, testing requirements may differ depending

on institutional type (e.g., community college or four-year university), although

students have similar linguistic needs across institutional type.

This situation is largely due to misunderstanding what second language learn-

ers must accomplish in terms of academic language once they have been admit-

ted to college. Both groups of NNESs have significant language development

needs. As such, though they meet required admission standards, many of these

students are likely to require further language development and instruction, as

indicated in the following statement:

Successful participation in academic and professional discourse com-

munities such as business, science, engineering, and medicine requires a

strong foundation of very advanced language and common core academic

skills. To participate successfully at the postsecondary level, learners

require additional knowledge and expertise in content, specialized vocab-

ulary, grammar, discourse structure, and pragmatics.

Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages [TESOL], 2010, p. 1

Assumption 2

The second major assumption that institutions make is that since second lan-

guage students are immersed in an English-speaking environment once they

enroll, their academic language skills (i.e., reading and writing) will naturally](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/17206790-250523115445-076e5bdb/75/Esl-Readers-And-Writers-In-Higher-Education-Understanding-Challenges-Providing-Support-Norman-W-Evans-24-2048.jpg)

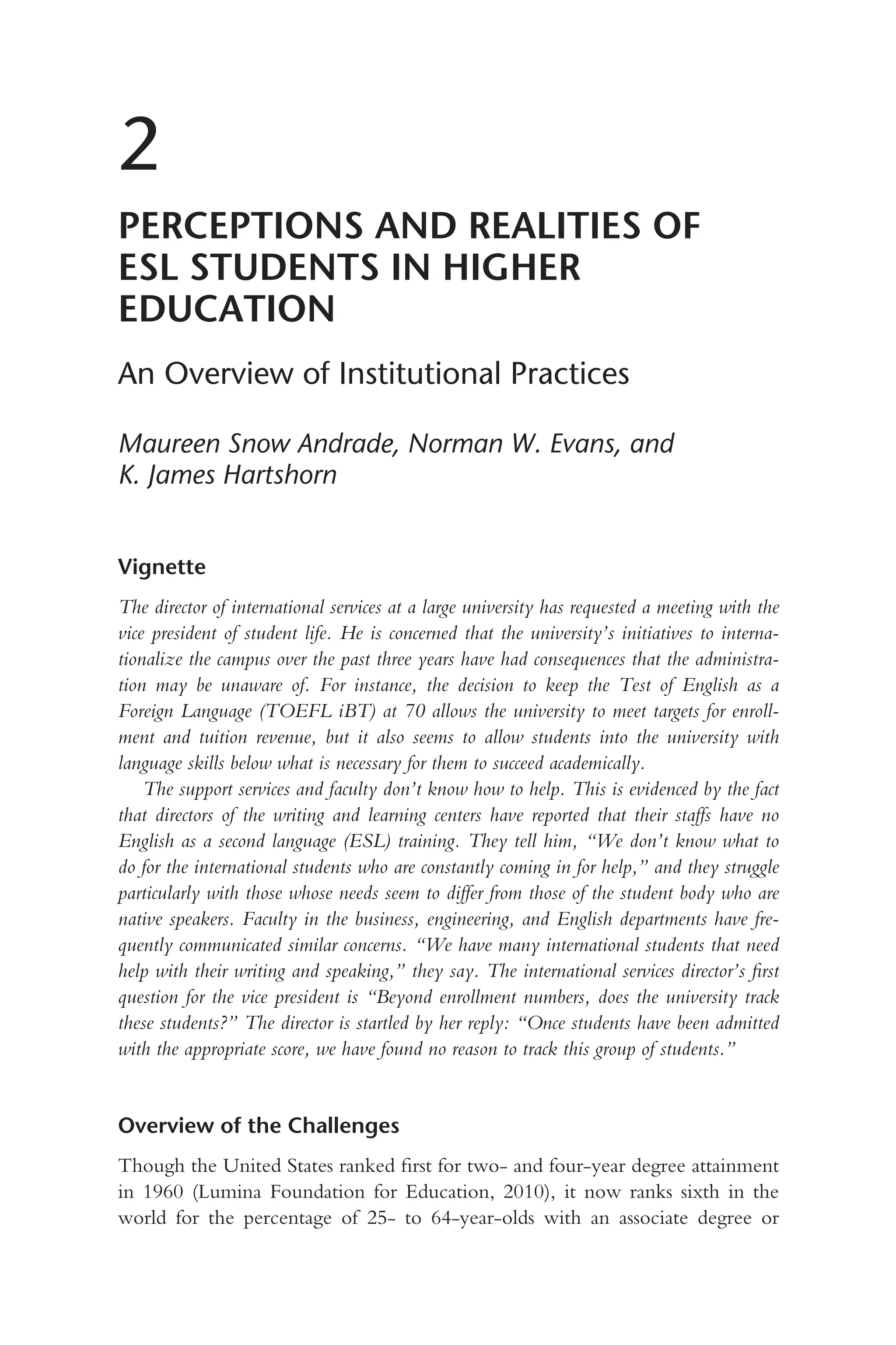

![Perceptions and Realities of ESL 21

support of some kind for their undergraduate students, and about half provide

services for graduate students. It is encouraging that these needs are recognized

at some institutions; however, several facts cannot be ignored. First, institutional

support is lacking for 20% of the undergraduate and 50% of graduate NNES.

Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, the support that is offered may not

be contributing to the long-term language development needs of NNES.

While some institutions offer language support in the form of skill centers,

coursework, tutoring programs, workshops, and modules (Andrade et al., 2014),

a close inspection of how institutions offer these services is informative. For

example, most language support services are optional. This suggests that, in

general, there is no systematic approach to supporting language development for

NNES over the course of their study in a university. Support services seem to

be tangential to students’ course of study. This approach is based in the “deficit

model of language learning” (Arkoudis, Baik, & Richardson, 2012, p. 2), which

assumes that once students have passed or are exempt from language admission

requirements, they have the necessary language skills to cope with the demands

of their studies. Such a model ignores two important facts: learning a language is

a long-term developmental process and an institution has a basic role to make

sure that the students it admits are appropriately supported to achieve success.

Inadequate Tracking

Data gathered by Andrade et al. (2014) from institutions across the United States

with high percentages of international students also suggest that tracking the

success of NNES is sorely lacking. Andrade et al. inquired to what extent insti-

tutions used key indicators such as GPA, retention, or persistence to graduation

to determine student success. Some institutions employed various methods of

tracking the success of NNES, but 40% of the institutions did not track success

in any way. Many of the survey participants perceived this as an institutional

weakness. Responses varied in explaining why this population was not tracked.

Some reasons were rather pragmatic. For example, one respondent indicated,

“We don’t have the manpower or resources to track these students,” while

another declared, “They all tend to do exceptionally well” (Andrade et al.,

2014, p. 215).

If we accept the premise that an institution has an ethical obligation to admit

only those students who are linguistically prepared or who are adequately sup-

ported by the institution, then systems that carefully monitor key indicators of

student success ought to be in place. Nationwide data further suggest that the

deficit model of language learning is commonly accepted. Comments made by

several survey participants illustrate this attitude succinctly: “If they meet our

admissions criteria, they have demonstrated adequate English understanding and

as such no further monitoring is performed”; “Once students have been

admitted with the appropriate score [note the use of the singular form], the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/17206790-250523115445-076e5bdb/75/Esl-Readers-And-Writers-In-Higher-Education-Understanding-Challenges-Providing-Support-Norman-W-Evans-40-2048.jpg)

![22 M. S. Andrade et al.

Admissions Office has found no reason to track students” (Andrade et al., 2014,

p. 214). Clearly, there is much room for improvement in the tracking proce-

dures on the part of institutions that admit and educate NNES.

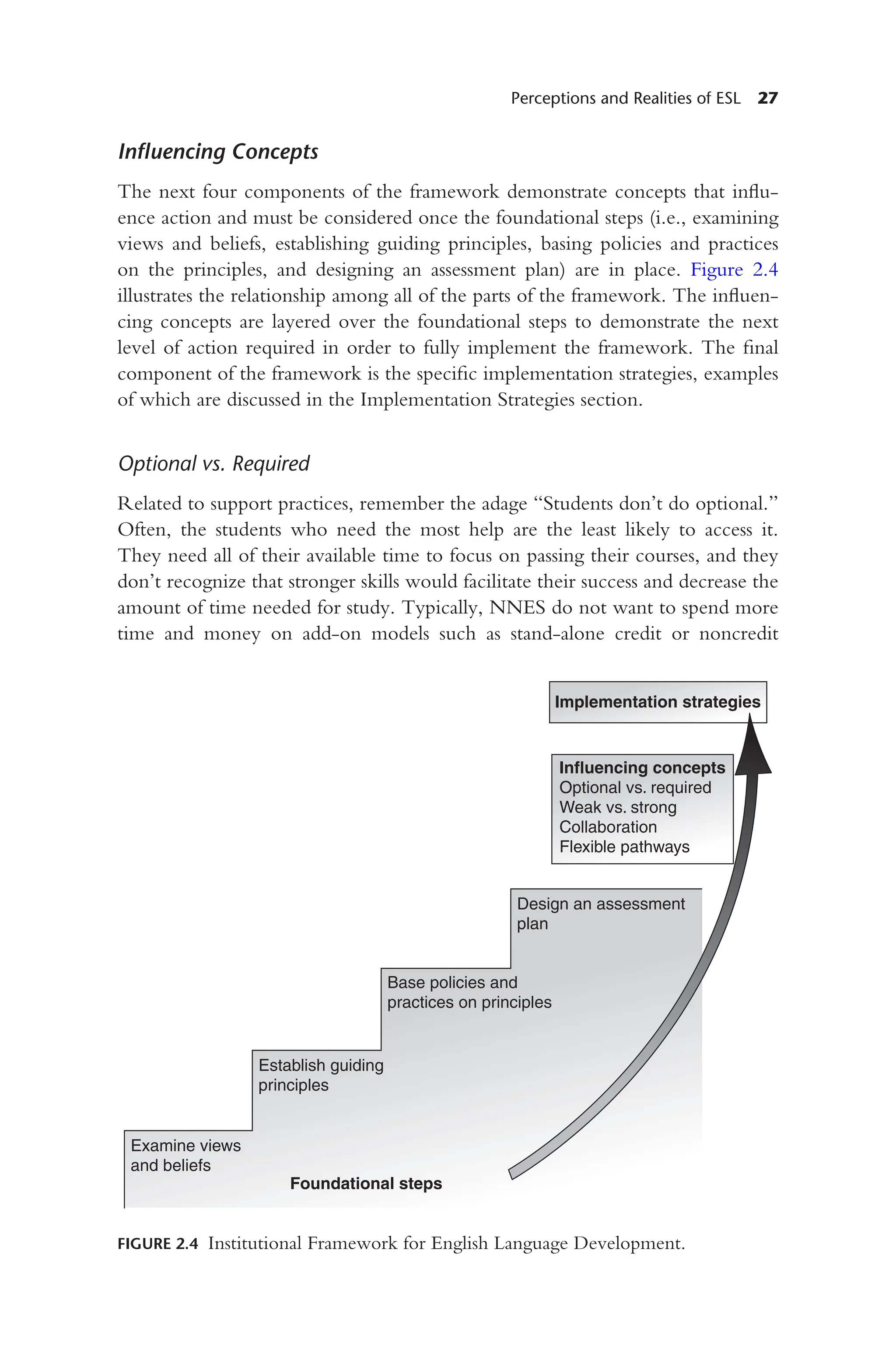

A Web of Disconnects

While the factors described are interconnected, they result in an overall dis-

connect in terms of NNES in higher education. Obviously, if students are not

identified as NNES in the admission process, they will not be required to dem-

onstrate their proficiency in English. Consequently, they will not receive

needed support. If they are not tracked as a distinct group (or two distinct

groups—international and resident), the institution can only assume they are

succeeding. Thus, institutions may be completely unaware of the challenges

these students face, and the students may be excluded from institutional,

national, and global discussions regarding student success.

Even if students are identified as NNES, which generally occurs for inter-

national students, lenient criteria often exempt them from pre-admission testing.

Frequently, further assessment after admission is not required. However, such

testing could be used with standardized proficiency tests to identify potential

weaknesses in academic reading and writing skills and types of support needed.

These oversights increase the likelihood that these students will face challenges

that could have been avoided. Such administrative practices also point to the

very real possibility that learners will graduate from the institution with weak

English skills, such as has been occurring in Australia, where 21.4% of higher

education enrollments consist of international students, most of them NNES

(Institute of International Education [IIE], 2012).

Australia represents an interesting case. Australian higher education institu-

tions admit NNES based on a standardized proficiency exam (Birrell, 2006).

They also offer residency to international students who graduate from Australian

universities in order to address work sector needs. However, these students have

had difficulty finding jobs due to their weak English language skills. Therefore,

the country instituted an English language proficiency test score requirement

that must be met to qualify for permanent residency. Nearly one-third of those

applying could not pass the test, even though the same score was required for

university admission.

Some of these students may have entered the country for other types of

educational programs (e.g., intensive English language study or high school) and

then entered universities. As such, they would not have had to submit scores

from a standardized English language proficiency test. Additionally, anecdotal

evidence suggests that universities may have lowered the English demands in

their courses and that students cope by getting help from native English speakers

(Birell, 2006). This is because universities do not want to require supplementary

English courses due to competition with English-medium universities in other](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/17206790-250523115445-076e5bdb/75/Esl-Readers-And-Writers-In-Higher-Education-Understanding-Challenges-Providing-Support-Norman-W-Evans-41-2048.jpg)