El documento analiza la epiglotitis (supraglotitis), enfocándose en su patogenia, etiología y características clínicas, así como en el diagnóstico y manejo de la enfermedad. La epiglotitis, que puede ser causada por infecciones bacterianas, virales o condiciones no infecciosas, puede llevar a una obstrucción de las vías respiratorias si no se trata adecuadamente. Se destaca la disminución de casos en niños debido a la vacunación, pero aún se observan incidentes en adultos, así como manifestaciones clínicas variadas según la edad y etiología del paciente.

![Reimpresión oficial de UpToDate

www.uptodate.com © 2024 UpToDate, Inc. y/o sus filiales. Todos los derechos reservados.

Epiglotitis (supraglotitis): características clínicas y diagnóstico

INTRODUCCIÓN

En este artículo se analizarán la patogenia, la etiología y las características clínicas de la epiglotitis (también llamada supraglotitis). El tratamiento y la prevención de la epiglotitis se analizan

por separado. (Véase "Epiglotitis (supraglotitis): tratamiento" ).

DEFINICIÓN

La epiglotitis es la inflamación de la epiglotis y las estructuras supraglóticas adyacentes, principalmente debido a una infección [ 1 ]. Sin tratamiento, la epiglotitis puede progresar hasta

convertirse en una obstrucción de las vías respiratorias potencialmente mortal. En la tabla ( tabla 1 ) se ofrece una descripción general rápida del reconocimiento y el tratamiento de la

epiglotitis en niños .

ANATOMÍA

La epiglotis forma la pared posterior del espacio valécular que se inserta en la base de la lengua ( figura 1 ). Está conectada por ligamentos al cartílago tiroides y al hueso hioides y

consiste en un cartílago delgado que está cubierto anteriormente por una capa epitelial escamosa estratificada. Esta capa escamosa también cubre el tercio superior de la superficie

posterior, donde se fusiona con el epitelio respiratorio que se extiende hacia la laringe. El epitelio y la lámina propia debajo están firmemente adheridos en la superficie posterior (laríngea) y

unidos de manera flexible en la superficie anterior (lingual). Esto crea un espacio potencial en la superficie lingual para que se acumule el líquido del edema.

PATOGENESIA

La epiglotitis es causada con mayor frecuencia por una infección, aunque la ingestión de cáusticos, la lesión térmica y el traumatismo local son etiologías no infecciosas importantes. La

epiglotitis infecciosa es una celulitis de la epiglotis, los pliegues ariepiglóticos y otros tejidos adyacentes. Es el resultado de una bacteriemia y/o una invasión directa de la capa epitelial por el

organismo patógeno [ 2,3 ]. La nasofaringe posterior es la fuente primaria de patógenos en la epiglotitis. El traumatismo microscópico de la superficie epitelial (p. ej., daño de la mucosa

durante una infección viral o de alimentos durante la deglución) puede ser un factor predisponente. Con menor frecuencia, las afecciones no infecciosas causan quemaduras locales o

equimosis de la epiglotis y las estructuras adyacentes.

Tanto en la etiología infecciosa como en la no infecciosa, la hinchazón de la epiglotis es resultado del edema y la acumulación de células inflamatorias en el espacio potencial entre la capa

epitelial escamosa y el cartílago epiglótico. La superficie lingual de la epiglotis y los tejidos periepiglóticos tienen abundantes redes de vasos linfáticos y sanguíneos que facilitan la

propagación de la infección y la posterior respuesta inflamatoria. Una vez que comienza la infección, la hinchazón progresa rápidamente hasta afectar toda la laringe supraglótica (incluidos

los pliegues ariepiglóticos y los aritenoides) [ 3,4 ]. Las regiones subglóticas generalmente no se ven afectadas; la hinchazón se detiene por el epitelio fuertemente unido a nivel de las

cuerdas vocales.

La hinchazón supraglótica reduce el calibre de las vías respiratorias superiores, lo que provoca un flujo de aire turbulento durante la inspiración (estridor) [ 3 ]. Otros mecanismos de

obstrucción del flujo de aire pueden incluir la curvatura posterior e inferior de la epiglotis (que actúa como una válvula de bola, obstruyendo el flujo de aire durante la inspiración pero

permitiendo la exhalación) y la aspiración de secreciones orofaríngeas [ 2,3 ].

La obstrucción de las vías respiratorias, que puede dar lugar a un paro cardiopulmonar, puede progresar rápidamente. Los signos de obstrucción grave de las vías respiratorias superiores

(p. ej., estridor/estertor, retracción intercostal y supraesternal, taquipnea y cianosis) pueden estar ausentes hasta una fase avanzada del proceso patológico, cuando la obstrucción de las

vías respiratorias es casi completa [ 5,6 ]. Se han notificado paros respiratorios extrahospitalarios debidos a una obstrucción aguda de las vías respiratorias, con resultado de muerte, en

niños y adultos [ 7,8 ].

ETIOLOGÍA

Infecciosa : la epiglotitis puede ser causada por varios patógenos bacterianos, virales y fúngicos ( tabla 2 ):

®

autor: Dr. Charles R Woods, doctor en medicina y máster

editores de sección: Dr. Glenn C. Isaacson, FAAP, Dr. Mark I. Neuman, máster en salud pública

editor adjunto: Dr. James F. Wiley, II, máster en Salud Pública

Todos los temas se actualizan a medida que hay nueva evidencia disponible y se completa nuestro proceso de revisión por pares .

Revisión de literatura actualizada hasta: julio de 2024.

Este tema se actualizó por última vez el 20 de diciembre de 2023.

Patógenos bacterianos – Los patógenos bacterianos son la etiología infecciosa identificada con mayor frecuencia para la epiglotitis. A pesar de la rápida disminución de la epiglotitis

infecciosa entre los niños inmunizados en la era posterior a la vacuna conjugada, Haemophilus influenzae tipo b (Hib) sigue siendo una etiología importante, principalmente en niños no

vacunados o inmunizados de forma incompleta. Además, según pequeñas series de casos, todavía se puede aislar Hib en niños y adultos completamente inmunizados [ 9-13 ].

●

Además de Hib, los aislamientos bacterianos de pacientes inmunocompetentes con epiglotitis también incluyen:

Staphylococcus aureus (incluidas las cepas resistentes a la meticilina [ 14-16 ])

•

Streptococcus pneumoniae [ 16,17 ]

•

Streptococcus pyogenes y otros estreptococos [ 16,18,19 ]

•

Neisseria meningitidis [ 16,20,21 ]

•](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epiglotitissupraglotitiscaracteristicasclinicasydiagnostico-uptodate-241008124850-c9ab38ca/75/Epiglotitis-supraglotitis-caracteristicas-clinicas-y-diagnostico-UpToDate-pdf-1-2048.jpg)

![La epiglotitis necrosante puede complicar las infecciones de las vías respiratorias superiores y puede observarse en huéspedes inmunocomprometidos (incluidos los niños [ 28,38 ]) y,

raramente, en huéspedes inmunocompetentes [ 38,39 ].

No infecciosa : la epiglotitis puede acompañar a la inhalación de humo (consulte “Lesiones por inhalación de calor, humo o irritantes químicos” ). Por lo demás, la epiglotitis no infecciosa

suele ser poco frecuente. Los informes de casos y las series de casos describen la epiglotitis como complicación de las siguientes afecciones:

EPIDEMIOLOGÍA

Desde la introducción de las vacunas contra H. influenzae tipo b (Hib), la epiglotitis se ha convertido en una enfermedad observada principalmente en adultos con una incidencia anual

estimada de 0,6 a 1,9 casos por 100.000 [ 16,55 ] y una edad media general de 45 a 49 años [ 56,57 ] (véase 'Infecciosas' más arriba). La epiglotitis se ha asociado con una serie de

condiciones comórbidas, incluyendo hipertensión, diabetes mellitus, enfermedad renal terminal, abuso de sustancias y deficiencia inmunológica [ 58-64 ]. Además, el índice de masa

corporal (IMC) >25, diabetes mellitus, neumonía concurrente y presencia de un quiste epiglótico al ingreso parecen ser factores asociados con una mayor gravedad de la epiglotitis [ 65 ].

La incidencia anual de epiglotitis entre los niños ha disminuido drásticamente desde la introducción de las vacunas Hib, con una incidencia anual estimada de Hib tan baja como dos casos

por cada 10 millones de niños en poblaciones con altas tasas de inmunización [ 55,66-74 ]. Además, como Hib se ha convertido en una causa menos frecuente de epiglotitis en los niños, se

ha vuelto más común entre los niños en edad escolar y adolescentes que entre los niños en edad preescolar (<5 años de edad) [ 9,75 ].

PRESENTACIÓN CLÍNICA

Las características clínicas de la epiglotitis difieren según la edad, la gravedad y la etiología:

Aguda (fiebre y estridor) : la aparición abrupta y la progresión rápida (en cuestión de horas) de la obstrucción de las vías respiratorias superiores son características de la epiglotitis

bacteriana debida a Hib [ 6,76-80 ]. Esta presentación clásica de la epiglotitis por Hib es rara, pero aún puede ocurrir entre niños pequeños (<5 años de edad) en comunidades con un gran

número de pacientes no inmunizados. Las presentaciones agudas de epiglotitis con compromiso abrupto de las vías respiratorias también pueden ocurrir con (ver 'Etiología' arriba):

Los hallazgos clínicos de la epiglotitis aguda incluyen [ 6,58,81 ]:

Pasteurella multocida [ 16 ]

•

En el caso de los huéspedes inmunodeprimidos, además de las etiologías bacterianas mencionadas anteriormente, los aislamientos incluyen Pseudomonas aeruginosa , Serratia spp,

Enterobacter spp y flora anaeróbica.

Patógenos virales : las infecciones virales pueden causar epiglotitis o permitir una sobreinfección bacteriana en raras ocasiones. Los aislamientos notificados en pacientes con

epiglotitis incluyen:

●

Gripe, tipo a [ 22 ]

•

Gripe, tipo b [ 23 ]

•

Virus del herpes simple, tipos 1 y 2 [ 24-26 ]

•

Virus parainfluenza, tipo 3 [ 23 ]

•

Virus de Epstein-Barr [ 27 ]

•

Virus de inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) [ 28 ]

•

SARS-CoV-2 [ 29-33 ]

•

Patógenos fúngicos – Las infecciones fúngicas ( especies de Candida e Histoplasma capsulatum ) como causa de epiglotitis son raras y parecen ocurrir principalmente en pacientes

inmunodeprimidos [ 34-36 ]. Se ha descrito un caso probable de epiglotitis por Candida en un niño aparentemente sano [ 37 ].

●

Traumatismos locales de las vías respiratorias como:

●

Lesión térmica por:

•

Ingestión de bebidas o alimentos calientes [ 40-43 ]

-

Uso de cigarrillos electrónicos [ 44 ] o inhalación de objetos calientes durante el consumo de drogas ilícitas como el crack o la cocaína [ 45 ]

-

Traumatismo directo sobre la epiglotis [ 46,47 ]

•

Ingestión o inhalación de cáusticos [ 47,48 ]

•

Enfermedad linfoproliferativa o enfermedad de injerto contra huésped después del trasplante de médula ósea o de órgano sólido [ 49-51 ]

●

Trastornos granulomatosos crónicos que incluyen poliangeítis, sarcoidosis, lupus eritematoso sistémico, policondritis recidivante y enfermedad relacionada con la inmunoglobulina G4

(IgG4) [ 52,53 ]

●

La afectación granulomatosa de las vías respiratorias supraglóticas, con características obstructivas progresivas de las vías respiratorias durante varios meses, se ha descrito como la

manifestación evidente inicial de la enfermedad de Crohn en un informe de caso [ 54 ].

Los niños pequeños (<5 años de edad) con epiglotitis por H. influenzae tipo b (Hib) pueden presentar dificultad respiratoria, ansiedad y la característica postura de "trípode" o "olfateo" (

imagen 1 y imagen 2 ) en la que asumen una posición sentada con el tronco inclinado hacia adelante, el cuello hiperextendido y el mentón empujado hacia adelante en un

esfuerzo por maximizar el diámetro de la vía aérea obstruida [ 6 ]. Pueden ser reacios a acostarse [ 2 ]. Sin embargo, la presentación puede ser sutil ( imagen 3 ). A menudo hay

babeo. La tos generalmente está ausente.

●

Los niños mayores, adolescentes y adultos con epiglotitis infecciosa o no infecciosa pueden presentar dolor de garganta intenso, disfagia y babeo; un examen orofaríngeo

relativamente normal y dificultad respiratoria mínima.

●

Infecciones por otros patógenos

●

Lesión térmica de las vías respiratorias superiores (por ejemplo, inhalación de humo, ingestión de bebidas calientes o inhalación de objetos calientes durante el consumo de drogas

ilícitas)

●

Ingestión o inhalación de cáusticos

●](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epiglotitissupraglotitiscaracteristicasclinicasydiagnostico-uptodate-241008124850-c9ab38ca/75/Epiglotitis-supraglotitis-caracteristicas-clinicas-y-diagnostico-UpToDate-pdf-2-2048.jpg)

![Los pacientes con epiglotitis y obstrucción completa inminente de las vías respiratorias también pueden adoptar la postura del "trípode" ( imagen 1 ), una posición sentada con el tronco

inclinado hacia adelante, el cuello hiperextendido y el mentón empujado hacia adelante en un esfuerzo por maximizar el diámetro de las vías respiratorias obstruidas.

Los niños con epiglotitis generalmente no presentan ronquera ni tos, que son más características del crup. (Ver "Crup: características clínicas, evaluación y diagnóstico", sección sobre

'Presentación clínica' .)

La epiglotitis necrotizante ocurre raramente y se ha descrito en niños inmunocomprometidos e inmunocompetentes con una variedad de etiologías microbianas asociadas [ 82 ].

Subaguda (dolor de garganta intenso) : entre las poblaciones inmunizadas, la epiglotitis infecciosa es causada por otros patógenos bacterianos orofaríngeos y nasofaríngeos, incluidos S.

pneumoniae , S. pyogenes y otros estreptococos, S. aureus (incluidas las cepas resistentes a la meticilina) y H. influenzae no tipificable ; la epiglotitis por Hib es mucho menos común. Además,

se describen casos raros de epiglotitis viral y fúngica. (Véase "Infecciosa" más arriba).

Como resultado, predomina una presentación subaguda de epiglotitis infecciosa que consiste en [ 5,55,58,83,84 ]:

El estridor se presenta en una minoría de estos pacientes. Además, la obstrucción repentina de las vías respiratorias es mucho menos común, pero sigue siendo una posibilidad [ 56,85 ]. Por

lo tanto, la epiglotitis se ha convertido en una consideración importante en niños mayores, adolescentes y adultos que buscan atención médica por faringitis infecciosa aguda. (Véase

"Evaluación de la faringitis aguda en adultos" y "Evaluación del dolor de garganta en niños" ).

Las causas no infecciosas poco frecuentes de epiglotitis subaguda, que se observan predominantemente en pacientes inmunodeprimidos, incluyen la enfermedad linfoproliferativa, la

enfermedad de injerto contra huésped, la enfermedad granulomatosa crónica y la epiglotitis necrosante (véase “No infecciosas” más arriba) .

Manejo de la vía aérea

For patients with signs of impending complete airway obstruction, securing the airway is the focus of treatment as described in the rapid overview ( table 1). In these patients, airway

management necessarily precedes diagnostic evaluation [3]. (See "Epiglottitis (supraglottitis): Management" and "Technique of emergency endotracheal intubation in children" and

"Overview of advanced airway management in adults for emergency medicine and critical care".)

EXAMINATION

The approach to diagnosing epiglottitis, including which patients should undergo attempts at direct visualization, depend upon the patient's presentation and the clinician's suspicion for

epiglottitis ( algorithm 1).

Visualization of the epiglottis confirms the clinical diagnosis [13]; a soft-tissue lateral radiograph of the neck is an alternative approach that has reasonable sensitivity and specificity. (See

'Imaging' below.)

Signs of impending airway obstruction — There are rare reports of cardiorespiratory arrest in children with acute presentations of epiglottitis during attempts to visualize the epiglottis

[86]. These arrests have been attributed to functional airway obstruction (resulting from increased respiratory effort secondary to increased anxiety), aggravation of airway obstruction

caused by supine positioning, and/or laryngospasm.

Presumably, the patients who have arrested after visualization have had pre-existing, nearly complete obstruction. These patients would typically have fairly definitive signs of epiglottitis

(eg, severe respiratory distress, anxiety, "sniffing" position ( picture 2); signs of upper airway involvement, particularly stridor, drooling, or "tripod" posture ( picture 1); and no cough).

(See 'Acute (fever and stridor)' above.)

Emergency involvement of airway experts (eg, otolaryngologists and anesthesiologists with pediatric expertise) to evaluate and to secure the airway should occur prior to any attempts at

visualization in these patients. (See 'Diagnostic confirmation' below.)

Severe sore throat — In patients with sore throat and drooling in whom epiglottitis is a possibility but for whom other diagnoses are also likely ( table 3), cautious examination of the

throat is appropriate to determine the best management. These patients should have [87]:

The patient should be permitted to take a position of comfort in the upright position. Younger children may be held by the caregiver to reduce anxiety that could provoke increased

respiratory distress. If the child develops increased respiratory distress during the attempt to examine the throat, this effort should be discontinued.

Use of a head lamp permits better visualization of oropharyngeal structures and facilitates more precise and gentler placement of the tongue blade during examination. On examination of

the oral cavity and oropharynx in patients with epiglottitis, pooled secretions may be noted [3]. Occasionally, a swollen, red epiglottitis may be visible. The laryngotracheal complex may be

tender on neck palpation, particularly in the region of the hyoid bone [88-90].

Aspecto tóxico y malestar (agitación, inquietud, irritabilidad ( imagen 2 ))

●

Aparición repentina de fiebre alta (entre 38,8 y 40,0 °C)

●

Estridor

●

Babeando

●

Cambio en la voz (voz apagada, como de "papa caliente")

●

Dolor de garganta intenso y disfagia.

●

Dolor de garganta progresivo

●

Fiebre baja

●

Voz apagada ("patata caliente") o ronca

●

Dificultad para tragar

●

Babeando

●

Normal mental status

●

Absent or minimal of stridor

●

No or minimal increase in symptoms during agitation or exertion

●

No cyanosis

●](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epiglotitissupraglotitiscaracteristicasclinicasydiagnostico-uptodate-241008124850-c9ab38ca/75/Epiglotitis-supraglotitis-caracteristicas-clinicas-y-diagnostico-UpToDate-pdf-3-2048.jpg)

![However, the oropharyngeal examination is normal in the majority of patients with epiglottitis [5,83,91]. When oropharyngeal examination fails to permit visualization of the epiglottis,

clinicians may proceed to either plain radiography or laryngoscopy. (See 'Diagnostic confirmation' below.)

Nasolaryngoscopy, plain radiography, or visualization during direct laryngoscopy under general anesthesia in the operating room is frequently necessary to confirm the diagnosis. (See

'Diagnosis' below.)

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical suspicion — Epiglottitis typically presents in one of two ways:

Diagnostic confirmation — The diagnostic approach to patients with suspected epiglottitis varies based upon clinical findings ( algorithm 1).

Visualization of the epiglottis — Maintenance of the airway is the mainstay of treatment in patients with suspected epiglottitis. In patients with signs of total or near-total upper airway

obstruction, airway control necessarily precedes diagnostic evaluation ( algorithm 2), and confirmation is made by direct visualization. (See "Epiglottitis (supraglottitis): Management".)

Visualization of the epiglottis without performing endotracheal intubation should only be attempted in a setting where the airway can be secured immediately if necessary (eg, the

emergency department, intensive care unit, or operating room) and, whenever possible, by the appropriate airway experts (eg, anesthesiology and otolaryngologist or airway expert with

similar expertise). Methods include fiberoptic nasolaryngoscopy and/or indirect laryngoscopy with a 70-degree endoscope [87,92,93].

Examination findings that confirm epiglottitis include inflammation and edema of the supraglottic structures (epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and arytenoid cartilages) ( picture 4 and

picture 5) [5]. The false vocal cords may also be involved [83]. Estimated airway obstruction of ≥50 percent is an indication for endotracheal intubation or establishment of a surgical

airway.

Imaging

Plain radiographs — Soft-tissue lateral neck radiographs can confirm the diagnosis of epiglottitis but are not necessary in many cases in which the likelihood of epiglottitis is

sufficiently low (eg, immunized children with a hoarse voice and characteristic cough of croup), such that no imaging is indicated, or high, in which case direct visualization during airway

management in the operating suite is preferred.

Radiographs are most helpful in the evaluation of patients in whom epiglottitis is a possibility, but other conditions are more likely ( table 3) [94] (see 'Differential diagnosis' below).

Diagnosis may also be confirmed by radiography if direct visualization appears unsafe or is unsuccessful. Radiographs should be deferred if they increase the patient's level of anxiety or will

delay definitive airway management [58,72]. If it is necessary for the patient with more than a low likelihood of epiglottitis to be transported to the radiology department (ie, if portable

radiographs cannot be obtained), the patient must be accompanied by personnel skilled with advanced airway management and with proper equipment and medications. (See 'Visualization

of the epiglottis' above.)

Radiographic features of epiglottitis include [2,95]:

Based upon case series in adults, lateral neck films are abnormal (generally showing the classic "thumb sign") in 77 to 88 percent of patients with epiglottitis [13,59]. False-negative

radiographic findings appear to be more common when patients have received prior oral antimicrobial therapy [97]. If radiographs are negative or equivocal, but clinical suspicion for

epiglottitis remains high, then the provider should proceed with visualization during airway management (patients with signs of severe upper airway obstruction) or fiberoptic

nasolaryngoscopy and/or indirect laryngoscopy in a setting where the airway can be secured immediately. (See 'Visualization of the epiglottis' above.)

Ultrasonography — Bedside ultrasound evaluation of the epiglottis in adults has been described, but its role in diagnosing epiglottitis is unclear [98,99]. The ultrasonographic

appearance of epiglottitis in adults has been described as an "alphabet P sign" formed by an acoustic shadow of the swollen epiglottis and hyoid bone at the level of the thyrohyoid

membrane when imaged in longitudinal orientation [98]. An evaluation of ultrasound in 15 adults with epiglottitis and 15 healthy controls found that an increased anteroposterior diameter

Progressive, severe sore throat over several days – Epiglottitis should be suspected in older children, adolescents, and adults in whom the severity of sore throat is out of proportion

to the findings on oropharyngeal examination, particularly if significant dysphagia and drooling are present [5]. These patients are appropriate candidates for confirmation by direct

visualization of the upper airway or soft-tissue radiograph of the lateral neck.

●

Abrupt onset of fever, stridor, and respiratory distress over 24 hours – Acute epiglottitis with severe airway obstruction should be suspected in patients, especially those who are

un- or under-immunized against H. influenzae type b (Hib), who present with the characteristic clinical features including:

●

"Tripod" position ( picture 1)

•

Anxiety ( picture 2)

•

Sore throat

•

Stridor

•

Drooling

•

Dysphagia

•

Severe respiratory distress

•

Because of the potential for rapid progression to complete airway obstruction, the threshold for suspicion of epiglottitis should be low. These patients should undergo definitive airway

management. Direct visualization should be avoided. Soft-tissue radiograph of the lateral neck (portable if possible) may be helpful, but necessary personnel and equipment to

manage an acute airway event must remain with the patient at all times during the imaging process. Furthermore, imaging should not delay definitive airway management.

An enlarged epiglottis protruding from the anterior wall of the hypopharynx (the "thumb sign", ( image 1 and image 2)). In adults with epiglottitis, the width of the epiglottis is

usually >8 mm [96].

●

Loss of the vallecular air space, a finding that may be underappreciated.

●

Thickened aryepiglottic folds ( image 2). In adults with epiglottitis, the width of the aryepiglottic folds is usually >7 mm [96].

●

Distended hypopharynx (nonspecific).

●

Straightening or reversal of the normal cervical lordosis (nonspecific).

●](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epiglotitissupraglotitiscaracteristicasclinicasydiagnostico-uptodate-241008124850-c9ab38ca/75/Epiglotitis-supraglotitis-caracteristicas-clinicas-y-diagnostico-UpToDate-pdf-4-2048.jpg)

![of the epiglottis at either lateral edge may also discriminate between those with and without epiglottitis. The lower limit of the diameter in adults with epiglottitis was 3.6 versus 3.2 mm

upper limit in the controls [100]. No pediatric experience with ultrasound has as yet been reported.

Laboratory studies — Laboratory studies should not be performed in young children with imminent complete airway obstruction until the airway is secured because agitation caused by

pain may worsen respiratory distress and precipitate sudden respiratory arrest.

In older children, adolescents, and adults with suspected epiglottitis, laboratory evaluation includes:

Most patients with epiglottitis have an elevated white blood cell count [5], but this finding is nonspecific.

The yield of blood and epiglottal cultures is discussed below. (See 'Microbiology' below.)

The immunologic evaluation for a child who develops Hib epiglottitis or pneumococcal epiglottitis despite having been immunized is discussed separately. (See "Epiglottitis (supraglottitis):

Management", section on 'Additional evaluation'.)

Microbiology — The etiologic diagnosis is sometimes made by culture of a pathogenic organism from the blood or the surface of the epiglottis.

Blood and epiglottic cultures should be obtained after the airway is secure [6,88]. Swabbing the epiglottis is difficult, potentially dangerous, and contraindicated in patients who are not

intubated [72,101].

Epiglottal cultures are positive in 33 to 75 percent of patients with epiglottitis [83,84,101,102].

Blood cultures are positive in approximately 70 percent of children with epiglottitis caused by Hib [103]. In children immunized against Hib, the yield of blood cultures is likely lower. In adult

case series, the yield of blood cultures ranges from 0 to 17 percent [5].

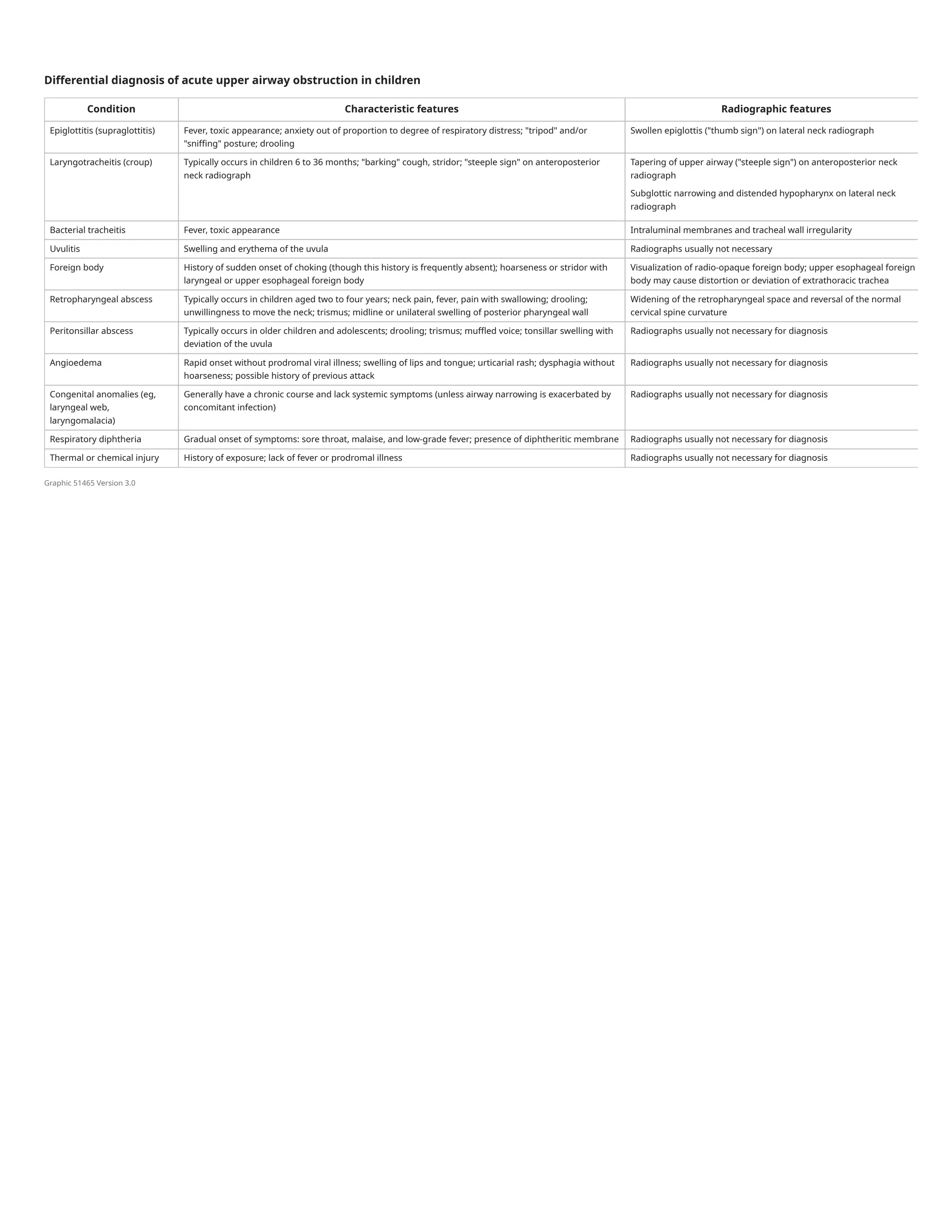

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Epiglottitis is an important consideration in older children, adolescents, and adults seeking care for sore throat as discussed separately. (See "Evaluation of acute pharyngitis in adults" and

"Evaluation of sore throat in children".)

The diagnostic approach ( algorithm 3) and emergency evaluation of acute upper airway obstruction in children are discussed separately. (See "Emergency evaluation of acute upper

airway obstruction in children".)

In young children (<5 years of age), the differential diagnosis of epiglottitis includes other causes of acute upper airway obstruction ( table 3):

Complete blood count with differential

●

Blood culture

●

In intubated patients, epiglottal culture

●

Croup – Epiglottitis is distinguished from croup by the absence of "barking" cough and the presence of anxiety and drooling. Children with croup generally are comfortable in the

supine position and have a normal-appearing epiglottis, when visualized, on examination. If obtained, lateral neck radiographs in patients with croup may demonstrate distention of

the hypopharynx during inspiration, subglottic haziness, and a normal epiglottis ( image 3). (See "Croup: Clinical features, evaluation, and diagnosis", section on 'Clinical

presentation'.)

●

Bacterial tracheitis – Bacterial tracheitis may be a complication of viral laryngotracheitis (croup) or a primary bacterial infection. Primary bacterial tracheitis may present with acute

onset of upper airway obstruction, fever, and toxic appearance, similar to epiglottitis. However, radiographs may demonstrate intraluminal membranes and irregularities of the tracheal

wall, as well as a normal epiglottis and supraglottic region ( image 4). Direct tracheoscopy may be necessary for diagnosis ( picture 6). (See "Bacterial tracheitis in children: Clinical

features and diagnosis", section on 'Clinical features'.)

●

Peritonsillar or retropharyngeal infection – Children with peritonsillar or retropharyngeal cellulitis/abscess, or other painful infections of the oropharynx, may present with drooling

and neck extension [104]. Children with these infections usually are not as toxic appearing or anxious as those with acute epiglottitis. Peritonsillar cellulitis or abscess is readily

identified on inspection of the oropharynx. For patients with a retropharyngeal abscess, a soft-tissue lateral neck radiograph may be helpful in confirming or excluding the presence of

epiglottitis. (See "Peritonsillar cellulitis and abscess" and "Retropharyngeal infections in children".)

●

Foreign bodies – Foreign bodies in the larynx or trachea can cause complete or partial airway obstruction that requires immediate treatment. Foreign bodies lodged in the upper

esophagus can cause tissue edema that compresses the airway, causing partial airway obstruction ( picture 7). Symptoms are likely to have an abrupt onset, and fever is absent. (See

"Emergency evaluation of acute upper airway obstruction in children", section on 'Foreign body' and "Foreign bodies of the esophagus and gastrointestinal tract in children".)

●

Angioedema (anaphylaxis or hereditary) – Allergic reaction or acute angioneurotic edema has rapid onset without antecedent cold symptoms or fever. The primary manifestations

are swelling of the lips and tongue, urticarial rash, dysphagia without hoarseness, and sometimes inspiratory stridor [105,106]. There may be a history of allergy or a previous attack.

(See "Anaphylaxis: Emergency treatment".)

●

Congenital anomalies and laryngeal papillomas – Congenital anomalies of the upper airway and laryngeal papillomas sometimes cause symptoms similar to those of epiglottitis.

However, these conditions have a chronic course and generally do not cause fever (unless symptoms are due to exacerbation of airway narrowing due to a concomitant viral infection).

(See "Congenital anomalies of the larynx".)

●

Diphtheria – The clinical presentation of diphtheria can be similar to that of epiglottitis. The onset of symptoms is typically gradual. Sore throat, malaise, and low-grade fever are the

most common presenting symptoms. A diphtheritic membrane (gray and sharply demarcated, ( picture 8)) may be present. Diphtheria is exceedingly rare in countries with high rates

of immunization for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis. (See "Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diphtheria" and "Group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis in children and

adolescents: Clinical features and diagnosis", section on 'Other bacterial infections'.)

●

Other causes of epiglottic enlargement – Other causes of epiglottic enlargement, such as neck radiation therapy, trauma, or thermal injury, generally can be elucidated by history

[40,107,108]. Laryngopyocele, an infectious complication of laryngoceles (which are uncommon, abnormal air sacs in the larynx), also may mimic epiglottitis both in clinical

presentation and on lateral neck radiographs [109].

●

Uvulitis – Patients with epiglottitis may also have uvulitis ( picture 9), although uvulitis can be caused by other oropharyngeal infections such as streptococcal pharyngitis [110-112].

●](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epiglotitissupraglotitiscaracteristicasclinicasydiagnostico-uptodate-241008124850-c9ab38ca/75/Epiglotitis-supraglotitis-caracteristicas-clinicas-y-diagnostico-UpToDate-pdf-5-2048.jpg)

![SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Use of UpToDate is subject to the Terms of Use.

REFERENCES

1. Klein MR. Infections of the Oropharynx. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2019; 37:69.

2. Tovar Padua, LJ and Cherry JD. Croup (laryngitis, laryngotracheitis, spasmodic croup, laryngotracheobronchitis, bacterial tracheitis, and laryngotracheobronchopneumonitis) and epiglott

itis (supraglottitis). In: Feigin and Cherry's Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 8th edition, Cherry JD, Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, Steinbach WJ, Hotez PJ (Eds), Elsevier, Philadelphia 201

9. Vol 1, p.175.

3. Glomb NWS and Cruz AT. Infectious disease emergencies. In: Fleisher and Ludwig's Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 7th ed, Shaw KN, Bachur RG (Eds), Wolters Kluwer, Philad

elphia 2016.

4. Sato S, Kuratomi Y, Inokuchi A. Pathological characteristics of the epiglottis relevant to acute epiglottitis. Auris Nasus Larynx 2012; 39:507.

5. Glynn F, Fenton JE. Diagnosis and management of supraglottitis (epiglottitis). Curr Infect Dis Rep 2008; 10:200.

6. Stroud RH, Friedman NR. An update on inflammatory disorders of the pediatric airway: epiglottitis, croup, and tracheitis. Am J Otolaryngol 2001; 22:268.

7. Schröder AS, Edler C, Sperhake JP. Sudden death from acute epiglottitis in a toddler. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2018; 14:555.

8. Morton E, Prahlow JA. Death related to epiglottitis. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2020; 16:177.

9. Shah RK, Roberson DW, Jones DT. Epiglottitis in the Hemophilus influenzae type B vaccine era: changing trends. Laryngoscope 2004; 114:557.

10. Tanner K, Fitzsimmons G, Carrol ED, et al. Haemophilus influenzae type b epiglottitis as a cause of acute upper airways obstruction in children. BMJ 2002; 325:1099.

11. Devlin B, Golchin K, Adair R. Paediatric airway emergencies in Northern Ireland, 1990-2003. J Laryngol Otol 2007; 121:659.

12. González Valdepeña H, Wald ER, Rose E, et al. Epiglottitis and Haemophilus influenzae immunization: the Pittsburgh experience--a five-year review. Pediatrics 1995; 96:424.

13. Solomon P, Weisbrod M, Irish JC, Gullane PJ. Adult epiglottitis: the Toronto Hospital experience. J Otolaryngol 1998; 27:332.

14. Somenek M, Le M, Walner DL. Membranous laryngitis in a child. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2010; 74:704.

15. Mazenq J, Retornaz K, Vialet R, Dubus JC. [Acute epiglottitis due to group A β-hemolytic streptococcus in a child]. Arch Pediatr 2015; 22:613.

16. Briem B, Thorvardsson O, Petersen H. Acute epiglottitis in Iceland 1983-2005. Auris Nasus Larynx 2009; 36:46.

17. Isakson M, Hugosson S. Acute epiglottitis: epidemiology and Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype distribution in adults. J Laryngol Otol 2011; 125:390.

18. Sivakumar S, Latifi SQ. Varicella with stridor: think group A streptococcal epiglottitis. J Paediatr Child Health 2008; 44:149.

19. Chroboczek T, Cour M, Hernu R, et al. Long-term outcome of critically ill adult patients with acute epiglottitis. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0125736.

20. Beltrami D, Guilcher P, Longchamp D, Crisinel PA. Meningococcal serogroup W135 epiglottitis in an adolescent patient. BMJ Case Rep 2018; 2018.

Definition – Epiglottitis (supraglottitis) refers to inflammation of the epiglottis and adjacent supraglottic structures. Without treatment, epiglottitis can progress to life-threatening

airway obstruction. A rapid overview of the recognition and management of epiglottitis is provided in the table ( table 1). (See 'Definition' above.)

●

Etiology – Since the introduction of vaccines against H. influenzae type b (Hib), epiglottitis has mostly become an adult disease that is caused by oro- and nasopharyngeal bacterial

pathogens other than Hib ( table 2). Immunocompromised patients may develop epiglottitis caused by opportunistic microorganisms. Hib epiglottitis remains a potential etiology in

unvaccinated or incompletely immunized children. (See 'Etiology' above.)

●

Clinical presentation:

●

Acute – Young children with Hib epiglottitis present with fever, stridor, drooling, respiratory distress, anxiety, and the characteristic "sniffing" posture ( picture 2), but the

presentation may be more subtle ( picture 3). (See 'Acute (fever and stridor)' above.)

•

Subacute – Older children, adolescents, and adults may present with a severe sore throat, dysphagia, drooling, and anterior neck pain but a relatively normal oropharyngeal

examination and mild respiratory distress. (See 'Subacute (severe sore throat)' above.)

•

Diagnostic approach – The diagnostic approach for patients with suspected epiglottitis is provided in the algorithm ( algorithm 1). For the patient with abrupt onset of fever, stridor,

and respiratory distress, airway management is the primary focus ( algorithm 2); the clinician should obtain emergency assistance from airway specialists (eg,

anesthesiologist/critical care specialist and an otolaryngologist) when possible. Visualization of the epiglottis during definitive airway management confirms the diagnosis. (See 'Clinical

suspicion' above and "Epiglottitis (supraglottitis): Management", section on 'Approach to airway management'.)

●

For the patient with sore throat and drooling in whom epiglottitis is a possibility but for whom other diagnoses are also likely ( table 3), cautious examination of the throat is

appropriate. Pooled secretions may be noted and, occasionally, a swollen, red epiglottitis may be visible. If the swollen epiglottis is not seen on routine oropharyngeal examination,

diagnosis of epiglottitis is confirmed by (see 'Visualization of the epiglottis' above and 'Imaging' above):

Fiberoptic nasolaryngoscopy or indirect laryngoscopy – Swelling and redness of the supraglottic structures (epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and arytenoid cartilages) ( picture 4 and

picture 5) on fiberoptic nasolaryngoscopy and/or indirect laryngoscopy with a 70-degree endoscope. Visualization of the epiglottis should occur in a setting where the airway can

be secured immediately if necessary. (See 'Diagnosis' above and 'Examination' above.)

•

Plain radiographs – In cases when visualization is not performed, soft-tissue lateral neck plain radiographs may be diagnostic (generally showing the classic "thumb sign" (

image 1 and image 2)). (See 'Plain radiographs' above.)

•

Plain radiography is most helpful in the evaluation of patients in whom epiglottitis is a possibility, but other conditions are more likely ( table 3) (see 'Differential diagnosis' above).

Diagnosis may also be confirmed by radiography if direct visualization appears unsafe or is unsuccessful. (See 'Imaging' above and 'Differential diagnosis' above.)

Although plain radiography can confirm the diagnosis of epiglottitis, it is not necessary in many cases in which the likelihood of epiglottitis is sufficiently low (eg, immunized children

with a hoarse voice and characteristic cough of croup), such that no imaging is indicated, or high, in which case direct visualization during airway management in the operating suite

is preferred.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epiglotitissupraglotitiscaracteristicasclinicasydiagnostico-uptodate-241008124850-c9ab38ca/75/Epiglotitis-supraglotitis-caracteristicas-clinicas-y-diagnostico-UpToDate-pdf-6-2048.jpg)