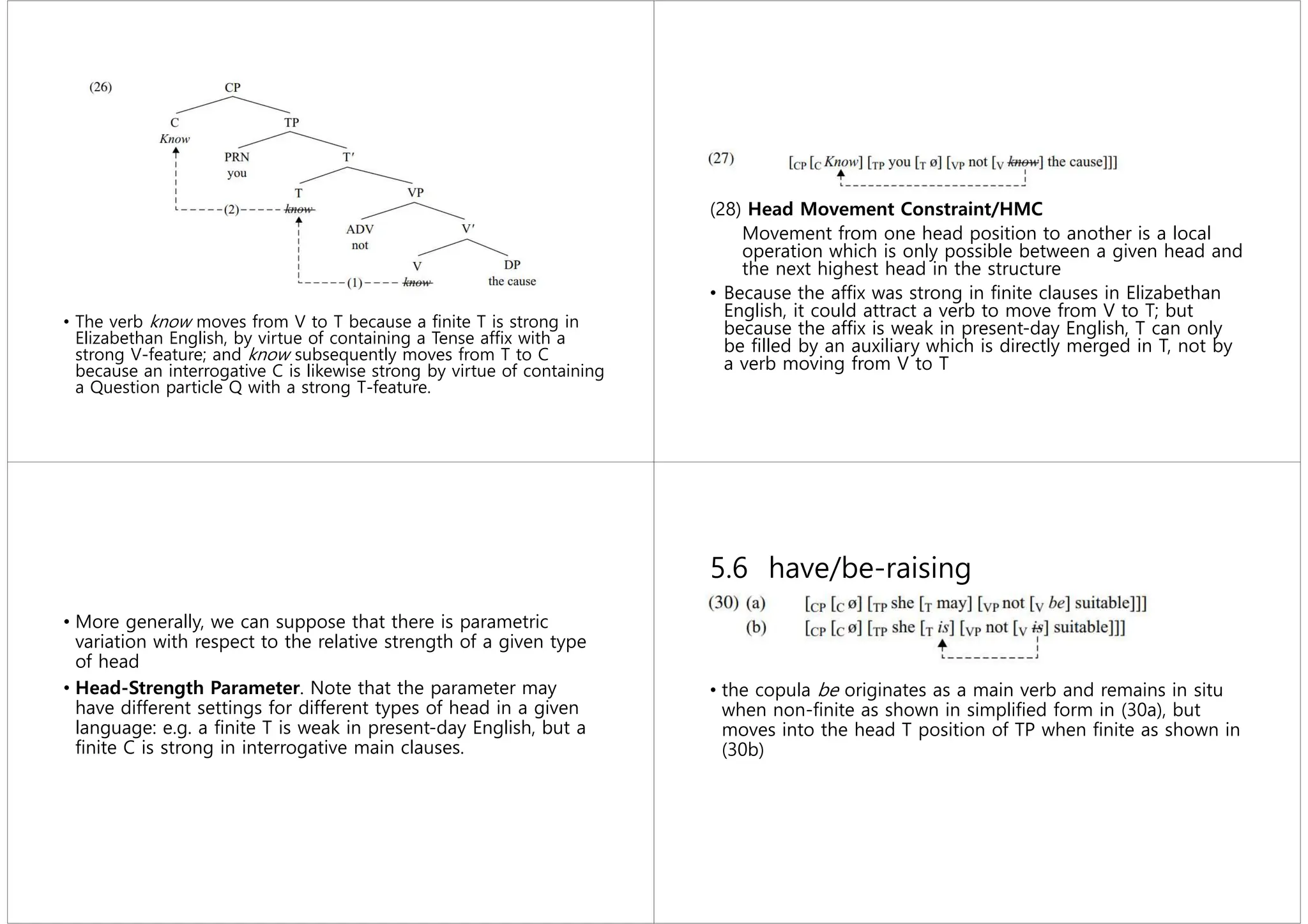

This document discusses head movement in syntax. It covers two types of head movement: T-to-C movement which affects auxiliaries in modern English, and V-to-T movement which occurred in earlier English. It examines examples of these movements and proposes mechanisms like copying and deletion. Other topics covered include have/be-raising, negation, and DO-support. Principles governing head movement like the Head Movement Constraint are also outlined.

![• a movement operation like auxiliary inversion as a composite

operation involving the two separate operations of copy-

merge and copy-deletion

• with the evidence from child grammars, we also have

evidence from adult grammars in support of the claim that a

moved auxiliary leaves behind a null copy

(16) [CP [C Should+Q] [TP they [T should] have called the police]]

5.4 V-to-T movement

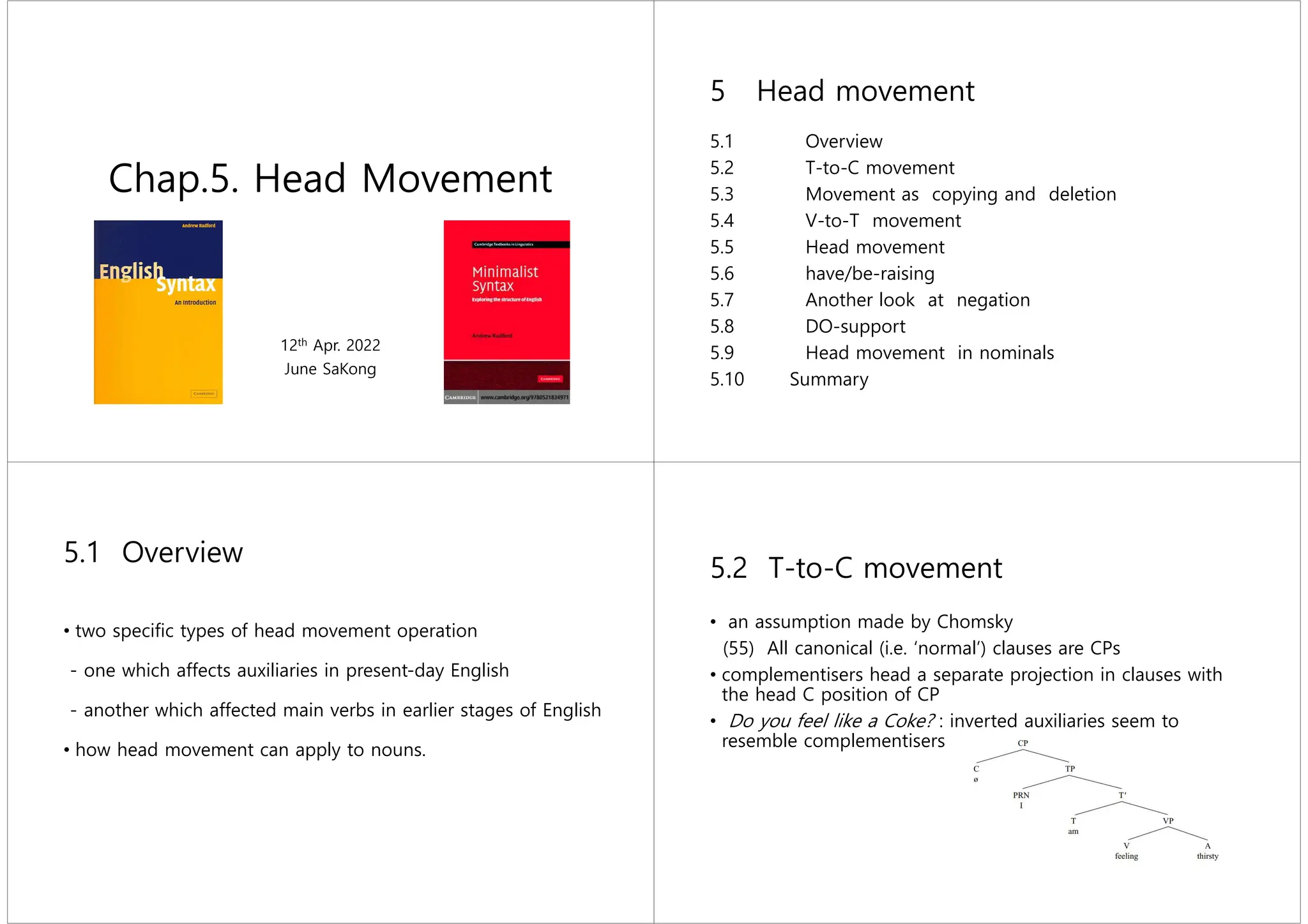

• V-to-T movement : was productive in Elizabethan English (i.e.

the English used during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, when

Shakespeare was writing), but is no longer productive in

present-day English

(18) (a) Thou hast not left the value of a cord

(Gratiano, The Merchant of Venice, 4.i)

(19) (a) Have I not heard the sea rage like an angry boar?

(Petruchio, The Taming of the Shrew, I.ii)

• (21) (a) I care not for her

(Thurio, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, V.iv)

• why the verb care should move from V to T?

• Using Chomsky’s strength metaphor, we can suppose that a

finite T is strong in Elizabethan English and so must be filled:

this means that in a sentence in which the T position is not

filled by an auxiliary, the verb moves from V to T in order to

fill the strong T position.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/englishsyntax2004chap5headmovement-240319132843-8439fa45/75/English_Syntax_2004_Chap5_Head_Movement-pdf-4-2048.jpg)

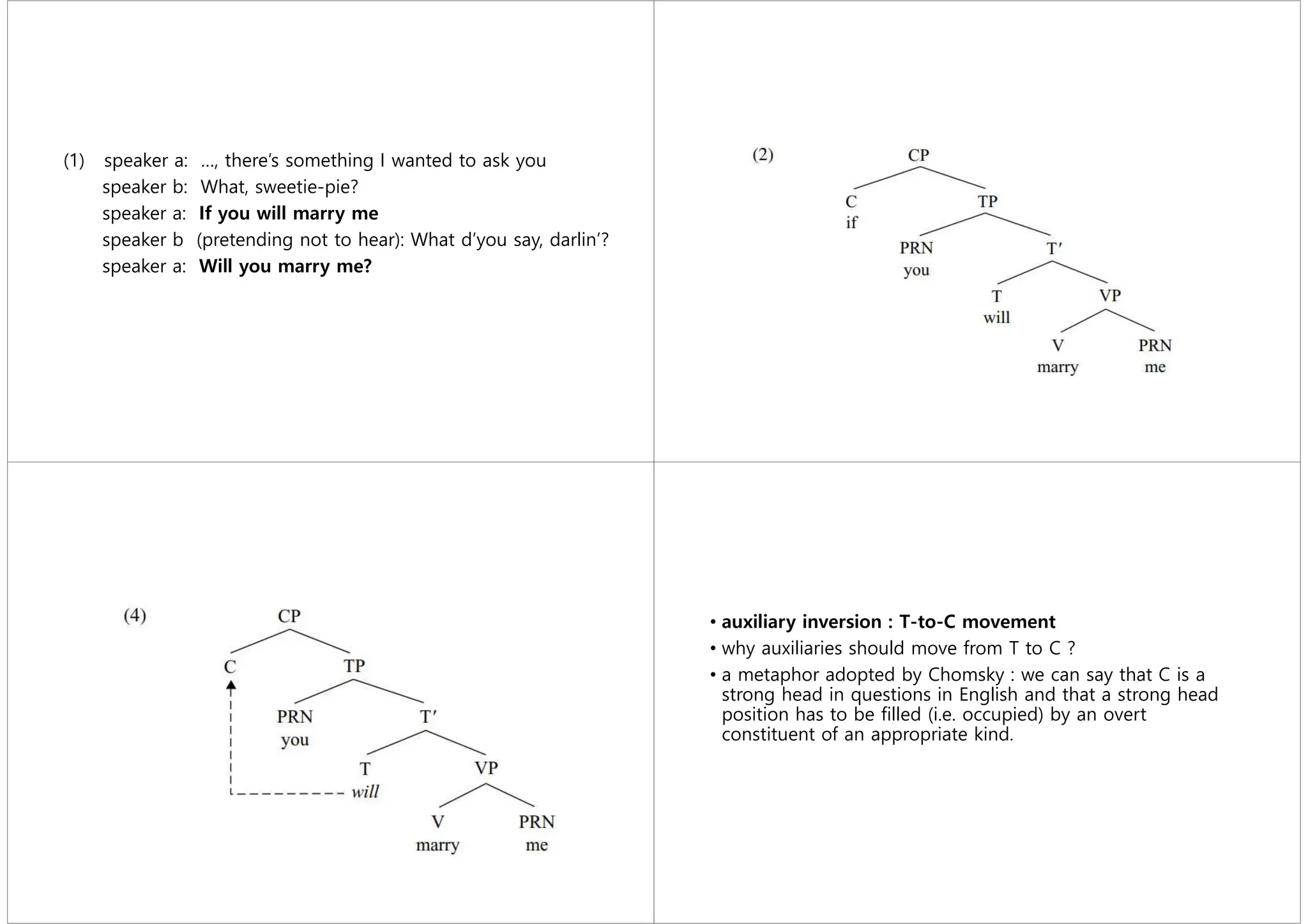

![• present-day English would have a BE-raising operation

moving finite forms of BE from the head V position in VP (or

the head AUX position in AUXP) into the head T position in

TP (an idea which dates back to Klima 1964). This would

mean that present-day English retains a last vestige of

raising-to-T.

• What do HAVE and BE have in common which differentiates

them from other verbs? An answer given by many traditional

grammars is that they have little if any inherent lexical

content (and for this reason are sometimes called light

verbs), and in this respect they resemble auxiliaries. Adopting

this intuition, we can say that a finite T in present-day English

can trigger movement of an auxiliary verb like HAVE/BE to T

(but not movement of a lexical verb to T).

5.7 Another look at negation

• in earlier varieties of English, sentences containing not also

contained the negative particle ne (with ne arguably serving

as the head NEG constituent of NEGP and not as its specifier).

This can be illustrated by the following Middle English

example taken from Chaucer’s Wife of Bath’s Tale

(35) A lord in his houshold ne hath nat every vessel al of gold

(lines 99–100)

‘A lord in his household does not have all his vessels made

entirely of gold’

• (37) [TP A lord . . . [T ne+hath+Tns][NEGP nat [NEG ne+hath] [VP [V

hath]every vessel al of gold]]]

• attaching to the negative prefix ne to form the complex head

ne+hath, the resulting complex head ne+hath then attaches

to a present-tense affix Tns in T, merger of the TP in (37) with

a null declarative complementiser will derive the CP structure

• By Shakespeare’s time, ne had dropped out of use, leaving

the head NEG position of NEGP null. Positing that not in

Elizabethan English is the specifier of a NEGP headed by a

null NEG constituent opens up the possibility that V moves

through NEG into T](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/englishsyntax2004chap5headmovement-240319132843-8439fa45/75/English_Syntax_2004_Chap5_Head_Movement-pdf-7-2048.jpg)

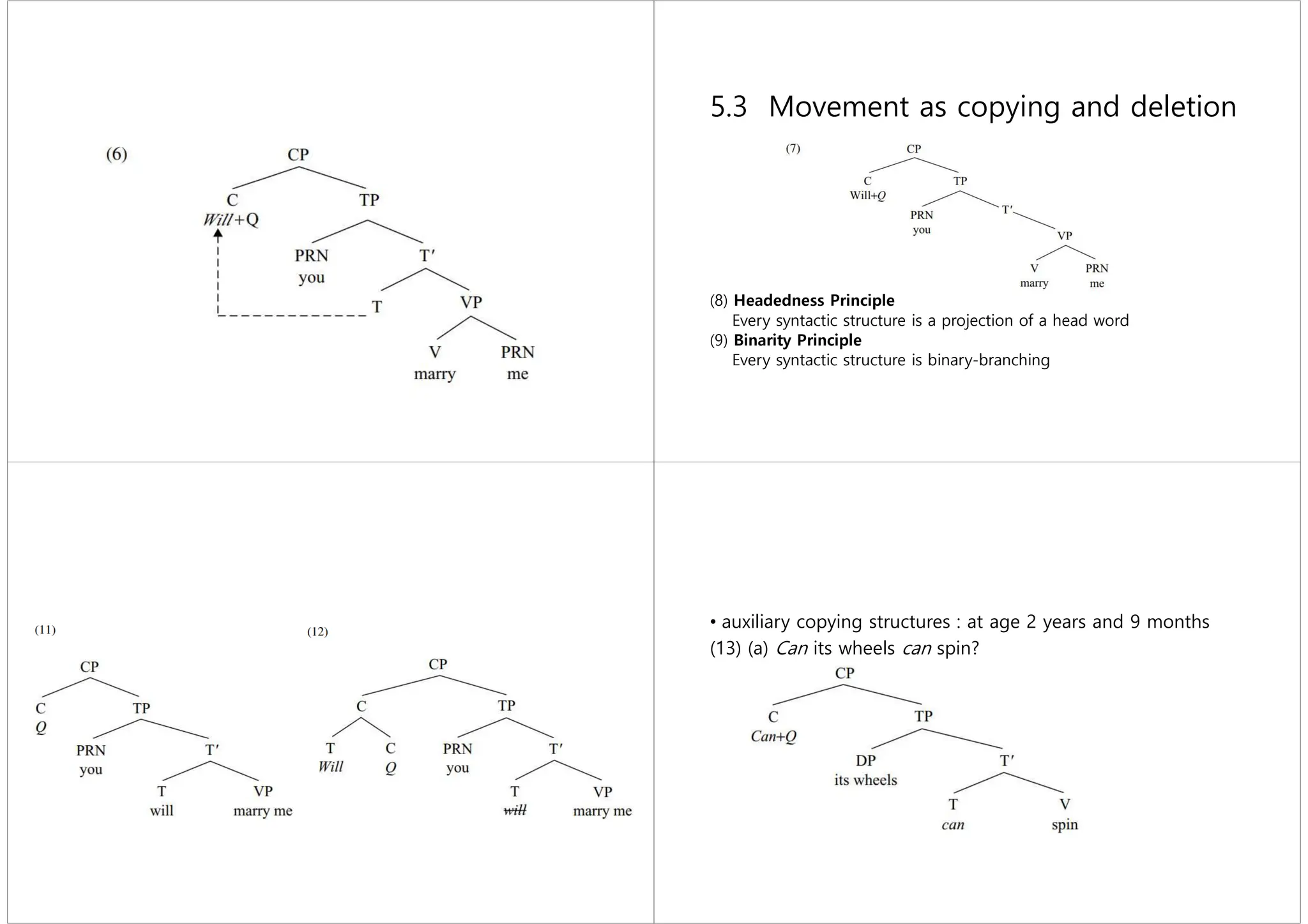

![(39) [CP [C ø] [TP I[T Tns][NEGP not [NEG ø] [VP [V care] for her]]]]

(40) Earliness Principle

Operations must apply as early as possible in a derivation

(43) Strict Cyclicity Principle/SCP

At a stage of derivation where a given projection HP is

being cycled/processed, only operations affecting the head

H of HP and some other constituent of HP can apply

5.8 DO-support

(44) I do not care for her

(46) [TP I[T DO+Tns][NEGP not [NEG ø] [VP [V care] for her]]]

(47) When the PF component processes a structure whose

head H contains an (undeleted) verbal affix which is not

attached to a verb

(i) if H has a complement headed by an overt verb, the affix

is lowered onto the relevant verb [= Affix Hopping]

(ii) if not (i.e. if H does not have a complement headed by

an overt verb), the expletive (i.e. semantically contentless)

verb DO is attached to the Tense affix [= DO-support]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/englishsyntax2004chap5headmovement-240319132843-8439fa45/75/English_Syntax_2004_Chap5_Head_Movement-pdf-8-2048.jpg)

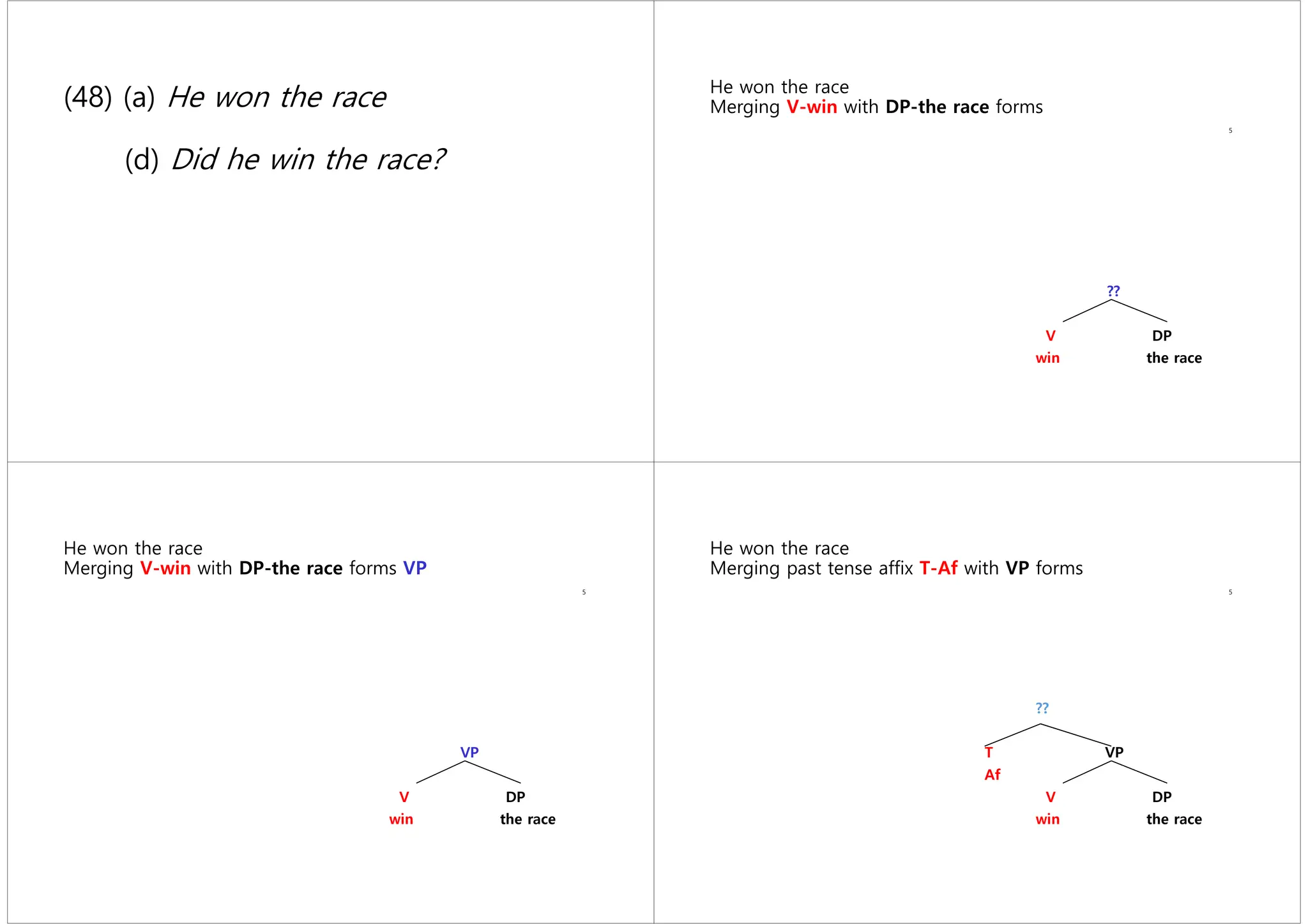

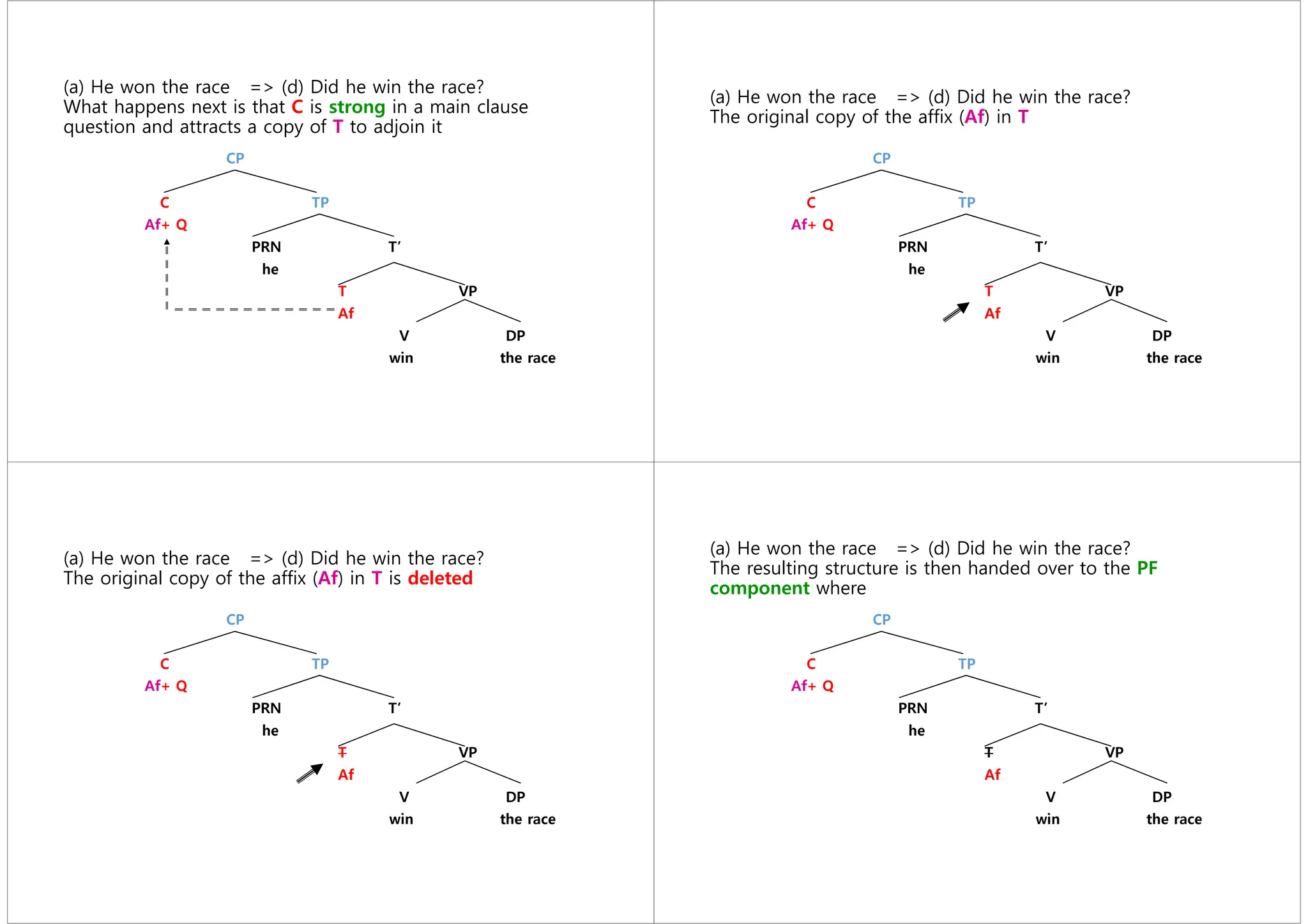

![(a) He won the race => (d) Did he win the race?

Nor can Af lower directly onto V win because this would

violate the Head Movement Constraint

CP

C TP

Af+ Q

PRN T’

he

T VP

Af

V DP

win the race

(a) He won the race => (d) Did he win the race?

Because it can’t find a verbal host by lowering onto T or V, Af

is instead spelled out as an appropriate form of DO

CP Affix attaches to the head of its complement…

C TP

Af+ Q

PRN T’

he

T VP

Af

V DP

win the race

(a) He won the race => (d) Did he win the race?

Because it can’t find a verbal host by lowering onto T or V, Af

is instead spelled out as an appropriate form of DO

CP Did he win the race?

C TP

Did + Q

PRN T’

he

T VP

Af

V DP

win the race

• Didn’t he win the race?

(54) [CP [C Q] [TP he [T Tns+n’t][NEGP n’t [NEG ø] [VP [V win] the

race]]]]

(55) [CP [C Tns+n’t+Q] [TP he [T Tns+n’t][NEGP n’t [NEG ø] [VP [V win]

the race]]]]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/englishsyntax2004chap5headmovement-240319132843-8439fa45/75/English_Syntax_2004_Chap5_Head_Movement-pdf-15-2048.jpg)

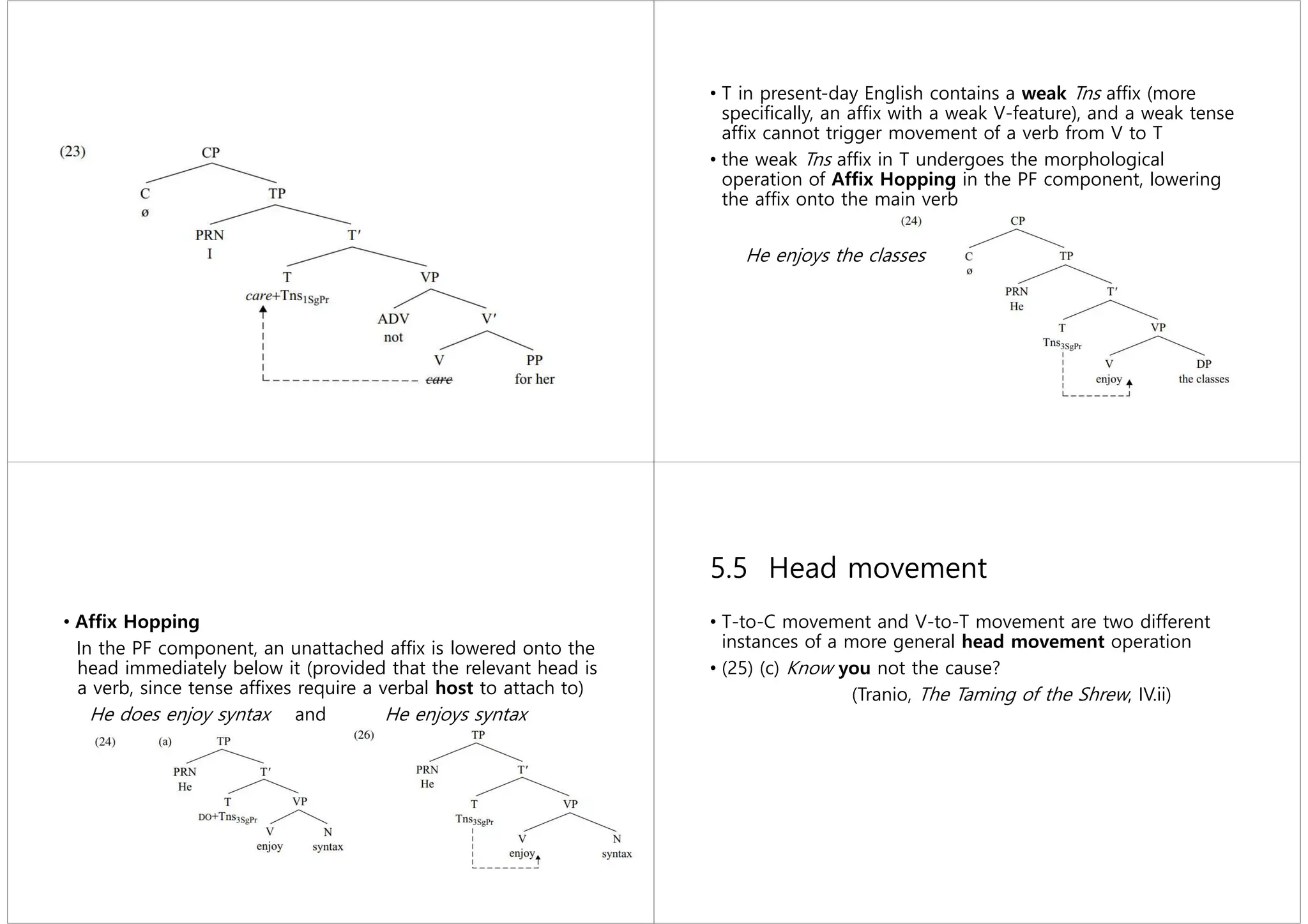

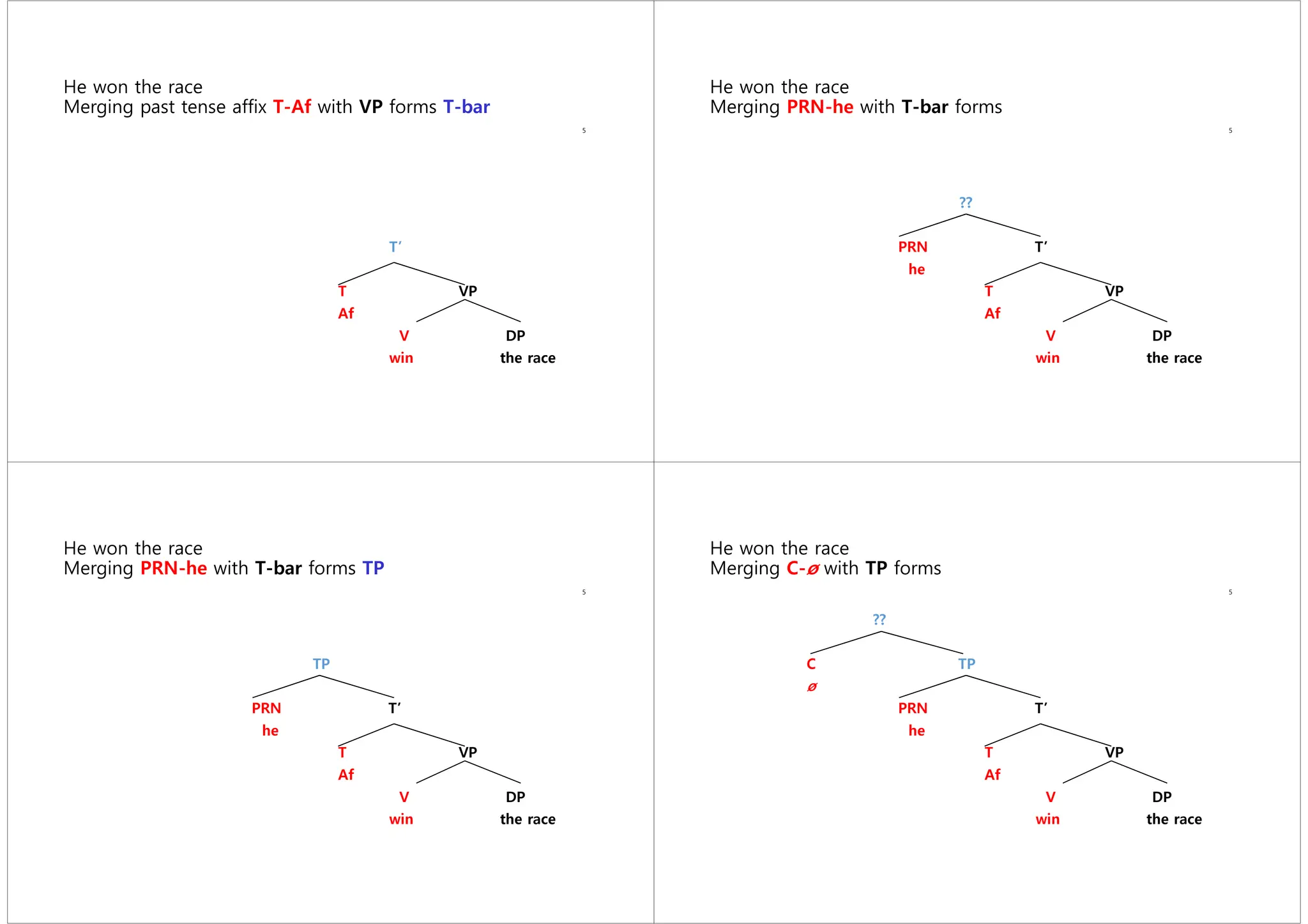

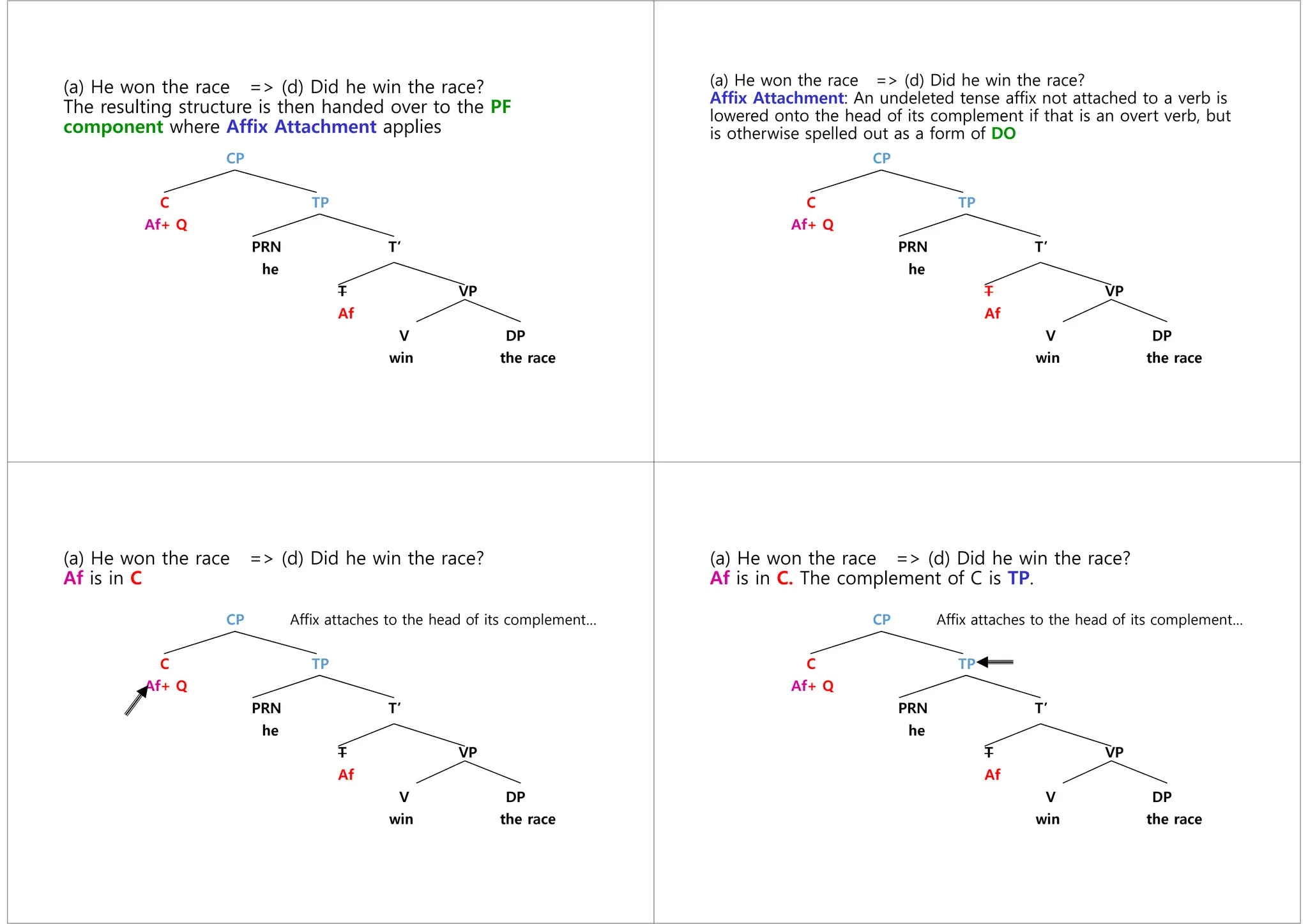

![5.9 Head movement in nominals

(57) (a) the Italian invasion of Albania

(b) l’invasione italiana dell’ Albania [Italian counterpart]

the invasion Italian of the Albania

(59) la grande invasione italiana dell’ Albania

the great invasion Italian of the Albania

(= ‘the great Italian invasion of Albania’)

(61) (b) a thing immortal [Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde]

some nice thing => some thing nice => something nice

(62) (b) bøkene hans om syntaks [Norwegian]

books+the his about syntax

• head movement may apply in nominal as well as clausal

structures

5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T

to adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/englishsyntax2004chap5headmovement-240319132843-8439fa45/75/English_Syntax_2004_Chap5_Head_Movement-pdf-16-2048.jpg)

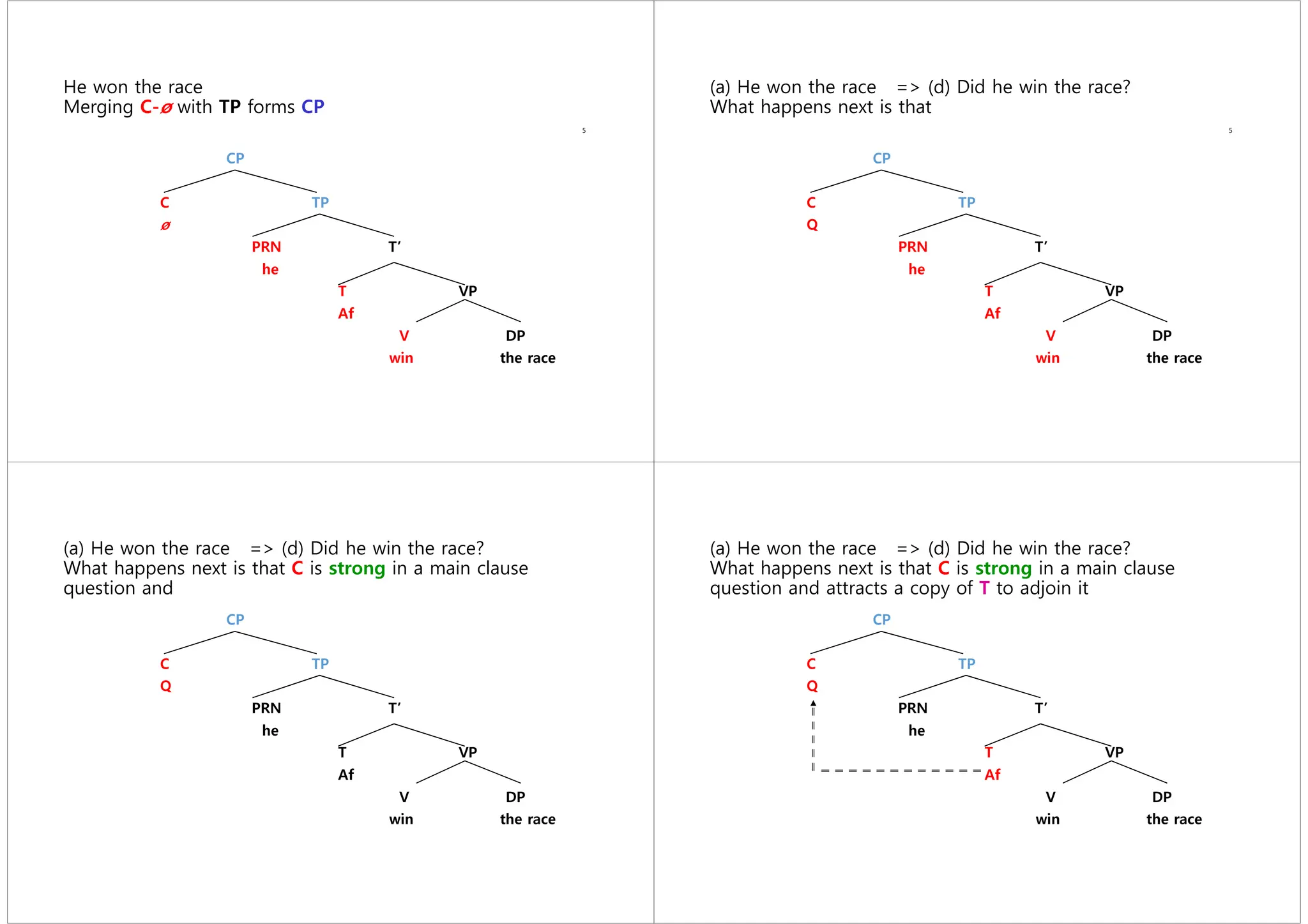

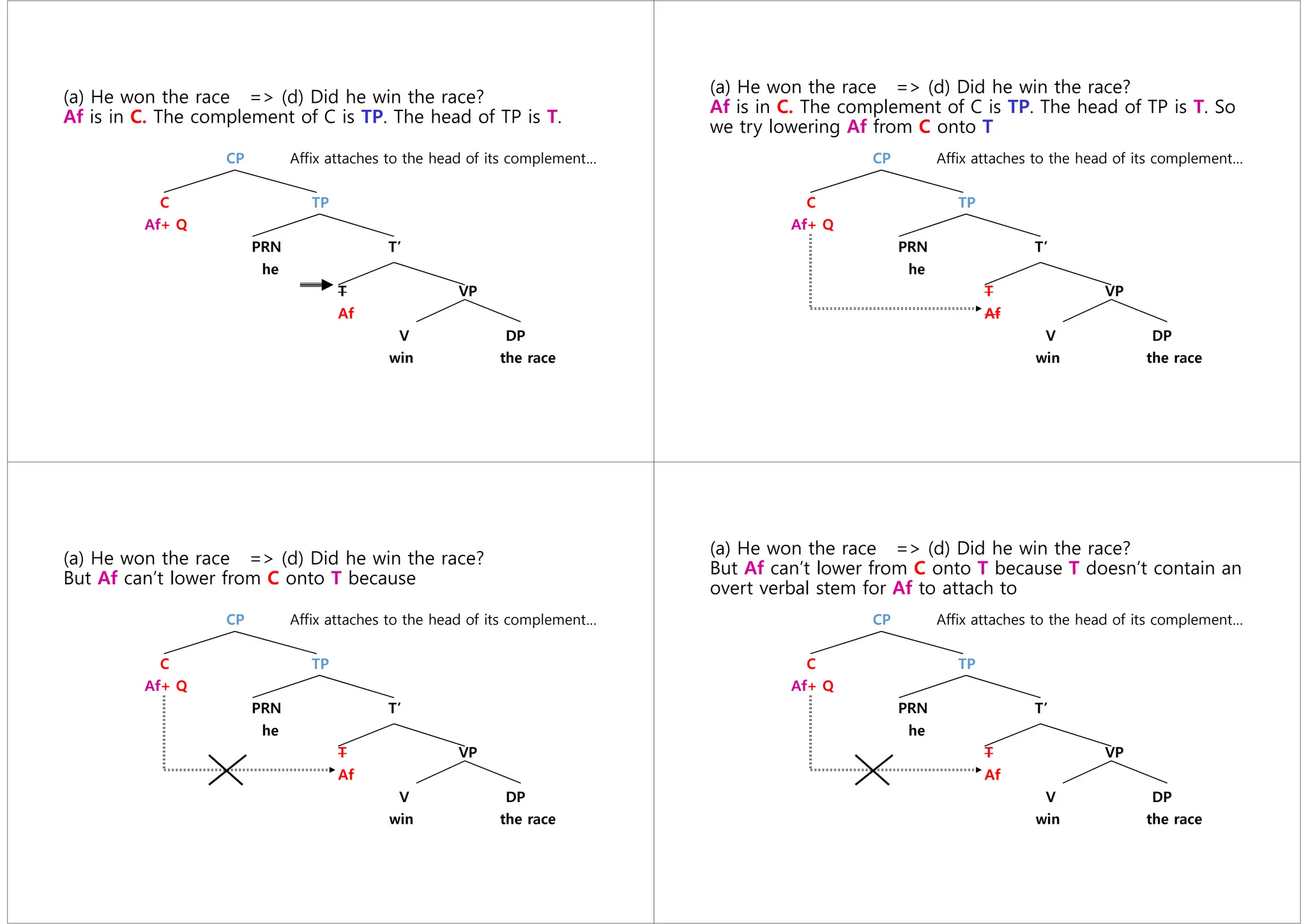

![5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T

to adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)

• Movement involves copying and deletion:

5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T

to adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)

• Movement involves copying and deletion:

I [T can] help

5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T

to adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)

• Movement involves copying and deletion:

I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T can] help

5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T

to adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)

• Movement involves copying and deletion:

I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T --] help?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/englishsyntax2004chap5headmovement-240319132843-8439fa45/75/English_Syntax_2004_Chap5_Head_Movement-pdf-17-2048.jpg)

![5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T

to adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)

• Movement involves copying and deletion:

I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T --] help?

• In Elizabethan English, finite T could attract V to T:

5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T

to adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)

• Movement involves copying and deletion:

I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T --] help?

• In Elizabethan English, finite T could attract V to T:

Thou [T dost] not [V love] me

5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T

to adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)

• Movement involves copying and deletion:

I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T --] help?

• In Elizabethan English, finite T could attract V to T:

Thou [T dost] not [V love] me > Thou [T lovest] not [V --] me

5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T

to adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)

• Movement involves copying and deletion:

I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T --] help?

• In Elizabethan English, finite T could attract V to T:

Thou [T dost] not [V love] me > Thou [T lovest] not [V --] me

• In Present-Day English, finite T is too weak to attract V to

move to T](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/englishsyntax2004chap5headmovement-240319132843-8439fa45/75/English_Syntax_2004_Chap5_Head_Movement-pdf-18-2048.jpg)

![5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T

to adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)

• Movement involves copying and deletion:

I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T --] help?

• In Elizabethan English, finite T could attract V to T:

Thou [T dost] not [V love] me > Thou [T lovest] not [V --] me

• In Present-Day English, finite T is too weak to attract V to

move to T (but can attract AUX)

•

5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T

to adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)

• Movement involves copying and deletion:

I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T --] help?

• In Elizabethan English, finite T could attract V to T:

Thou [T dost] not [V love] me > Thou [T lovest] not [V --] me

• In Present-Day English, finite T is too weak to attract V to

move to T (but can attract AUX)

• A tense affix attaches to the head of its complement, if

that is an overt verb stem: if not, the affix is spelled out as

a form of DO

5.10 Summary

• C in main-clause questions is strong/affixal and attracts T to

adjoin to it (= ‘Aux Inversion’)

• Movement involves copying and deletion:

I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T can] help > [C Can] I [T --] help?

• In Elizabethan English, finite T could attract V to T:

Thou [T dost] not [V love] me > Thou [T lovest] not [V --] me

• In Present-Day English, finite T is too weak to attract V to move

to T (but can attract AUX)

• A tense affix attaches to the head of its complement, if that is

an overt verb stem: if not, the affix is spelled out as a form of

DO

• Movement obeys Head Movement Constraint and Strict Cyclicity

Principle](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/englishsyntax2004chap5headmovement-240319132843-8439fa45/75/English_Syntax_2004_Chap5_Head_Movement-pdf-19-2048.jpg)