English is used widely as a lingua franca across the globe today. Approximately 80% of English speakers worldwide are non-native speakers, using English to communicate between different language groups. While English as a lingua franca (ELF) shares some similarities to Standard English, it also has its own grammatical structures and conventions that facilitate communication over strict adherence to rules. However, some scholars criticize ELF for promoting linguistic imperialism and negatively influencing native languages. Overall, ELF continues to flourish internationally and change the English language through unique local expressions.

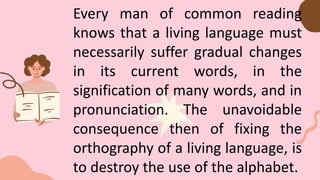

![This effect has, in a degree, already taken place in

our language; and letters, the most useful invention

that ever blessed mankind, have lost and continue to

lose a part of their value, by no longer being the

representatives of the sounds originally annexed to

them. Strange as it may seem, the fact is undeniable,

that the present doctrin [sic] that no change must be

made in writing words, is destroying the benefits of

an alphabet, and reducing our language to the

barbarism of Chinese characters in stead of letters.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/englishtoday-221003070435-c5fb291d/85/english-today-pptx-17-320.jpg)