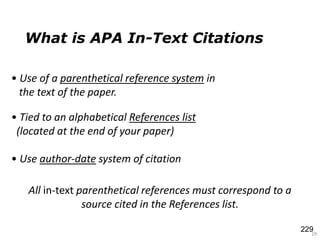

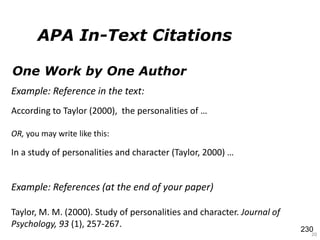

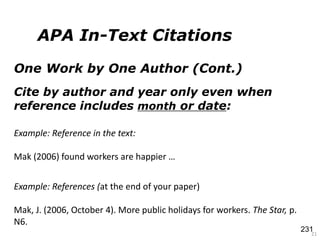

The document outlines the syllabus for an English course divided into 4 units. Unit 1 focuses on academic writing, with objectives of developing coherent ideas, supporting ideas with evidence, and writing effective arguments. Unit 2 covers incident reports, with the aim of enhancing language skills for problem detection and resolution. Unit 3 guides students in proofreading, editing, and crafting papers. Unit 4 teaches references and citations in APA style to improve scientific and scholarly writing. The overall syllabus aims to improve students' English language abilities in various types of academic writing.

![NURSING

PRACTICE &

SKILL

Authors

Tanja Schub, BS

Cinahl Information Systems, Glendale, CA

Mary Woten, RN, BSN

Cinahl Information Systems, Glendale, CA

Reviewers

Rosalyn McFarland, DNP, RN, APNP,

FNP-BC

Darlene Strayer, RN, MBA

Cinahl Information Systems, Glendale, CA

Nursing Executive Practice Council

Glendale Adventist Medical Center,

Glendale, CA

Editor

Diane Pravikoff, RN, PhD, FAAN

Cinahl Information Systems, Glendale, CA

December 25, 2015

Published by Cinahl Information Systems, a division of EBSCO Information Services. Copyright©2015, Cinahl Information Systems. All rights

reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by

any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cinahl Information Systems accepts no liability for advice

or information given herein or errors/omissions in the text. It is merely intended as a general informational overview of the subject for the healthcare

professional. Cinahl Information Systems, 1509 Wilson Terrace, Glendale, CA 91206

Incident Report: Writing

What is an Incident Report?

› An incident report (IR; also called accident report and an occurrence report) is a written,

confidential record of the details of an unexpected occurrence (e.g., a patient fall or

administration of the wrong medication) or a sentinel event (i.e., defined by The Joint

Commission [TJC] as an unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or

psychological injury, or the risk thereof) involving a patient, employee, or other person

(e.g., a visitor) who is present in the healthcare facility. An IR is used for internal risk

management and quality improvement purposes, and is not part of—nor is it mentioned in

—the permanent patient record if a patient is involved. An IR should be completed each

time an event occurs that deviates from the normal operation of the facility (e.g., a visitor

falls) or deviates from routine patient care (e.g., a medication error)

• What: The purpose for writing an IR is to document the details of an unexpected

occurrence or sentinel event. The written information is analyzed to identity changes that

need to be made in the facility or in facility processes to prevent recurrence of the event

and promote overall safety and quality health care

• How: Writing an IR involves providing an objective, detailed description of what

happened; typically the healthcare facility has a standardized form that is completed by

the person who witnesses the incident or is responsible for the area in which the incident

occurred in the case of an unwitnessed incident. The documented information can vary,

but typically an IR includes details regarding

–who witnessed the incident, which is typically the person reporting the incident

although in some cases there is more than one witness

–who was affected by the incident (e.g., patient, family member, nurse)

–what persons were notified (e.g., treating clinician, fire department)

–what actions or interventions were performed in response to the incident

–the condition of the patient, visitor, or employee who was affected by the incident

• Where: An IR should be completed in all healthcare settings according to facility

protocol

• Who: IRs can be completed by any licensed healthcare professional who participated

in or witnessed an incident. Writing an IR should never be delegated to unlicensed

personnel—although unlicensed personnel should report any witnessed incidents and

provide information that can be included in the IR—and are rarely completed in the

presence of a patient’s family members

What is the Desired Outcome of Writing an Incident Report?

› The desired outcome of writing an IR is to

• document the occurrence of an unexpected event that involves physical or psychological

injury to a patient, visitor or employee or that increases the risk for injury

• identity changes that need to be made in the facility or to facility processes in order to

prevent recurrence of the event and promote overall safety and quality health care

Why is Writing an Incident Report Important?

› Writing an IR is important because it can provide

• documentation of quality of care

149](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/english6thsemesterbsnnoteseducationalplatform-1-230819175239-90f99f70/85/English-6th-Semester-BSN-Notes-Educational-Platform-1-pdf-149-320.jpg)

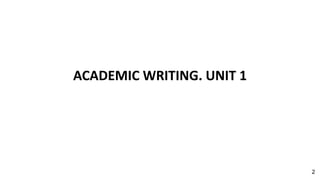

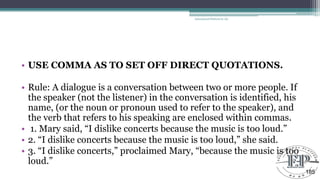

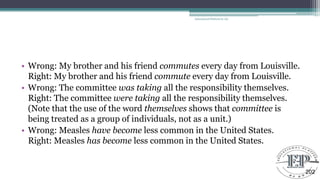

![• Avoid the apostrophe to mark possession with pronouns

A very common mistake is to place an apostrophe in the

possessive form of pronouns like its, yours, hers, ours, theirs.

Although this makes perfect sense, it is considered wrong.

() The book is old; its pages have turned yellow. [correct]

() The book is old; it’s pages have turned yellow. [incorrect, it’s is

a contraction of it is]

Educational Platform by AD

192](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/english6thsemesterbsnnoteseducationalplatform-1-230819175239-90f99f70/85/English-6th-Semester-BSN-Notes-Educational-Platform-1-pdf-192-320.jpg)

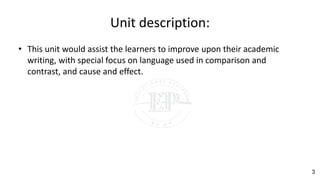

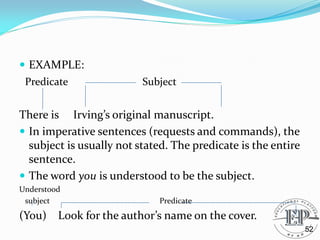

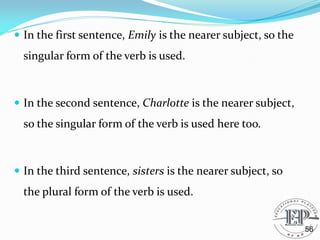

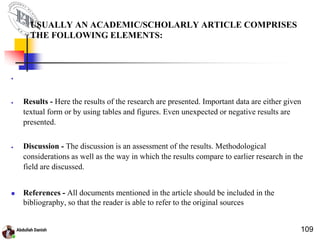

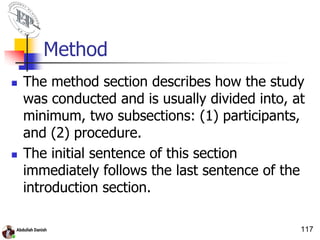

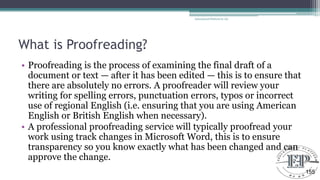

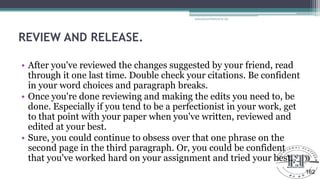

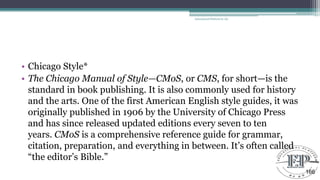

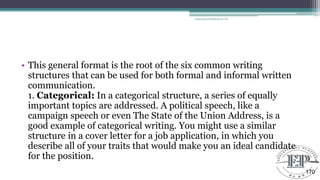

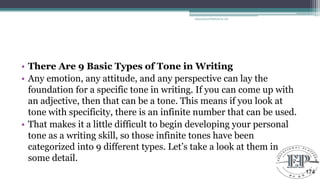

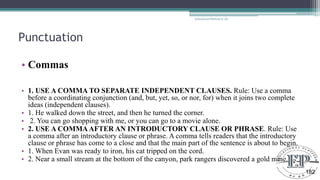

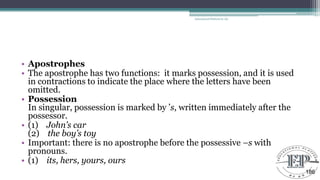

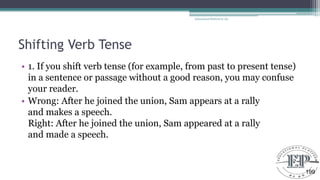

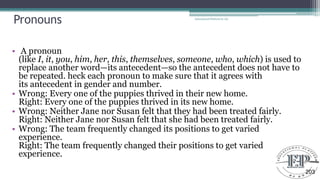

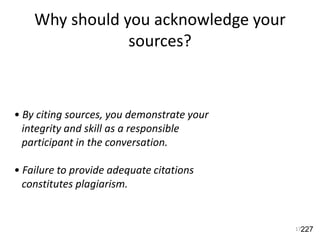

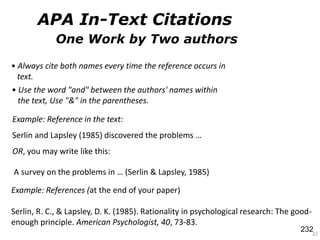

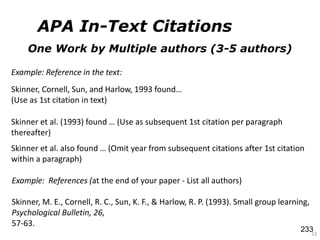

![• For works with 6 or more authors, the 1st

citation & subsequent citations use first

author et al. and year.

• et al means “and others”

24

Example: References (at the end of your paper) - *List the first six authors, … and the

last author]

Wolchik, S. A., West, S. G., Sandler, I. N., Tein, J., Coatsworth, D., Lengua, L., … Rubin,

L. H. (2000). An experimental evaluation of theory-based mother and mother-child

programs for children of divorce. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68,

843-856.

Example: Reference in the text:

Wolchik et al. (2000) studied the use of …

6 or More Authors

APA In-Text Citations

234](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/english6thsemesterbsnnoteseducationalplatform-1-230819175239-90f99f70/85/English-6th-Semester-BSN-Notes-Educational-Platform-1-pdf-234-320.jpg)

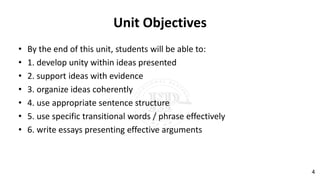

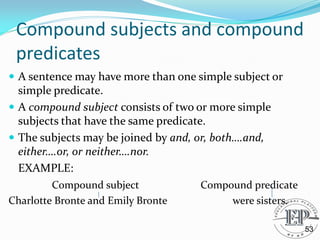

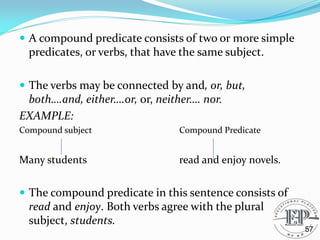

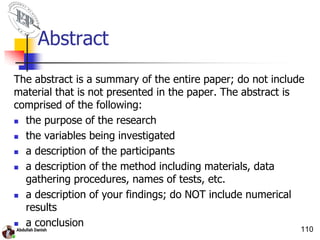

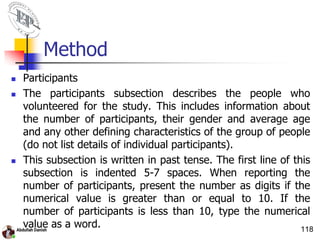

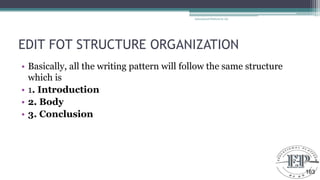

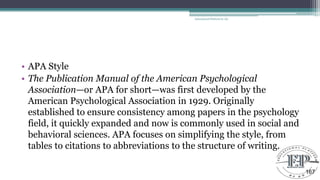

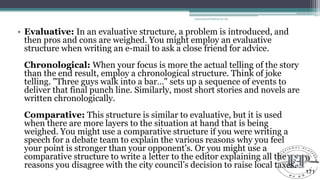

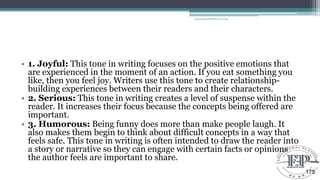

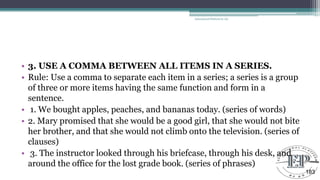

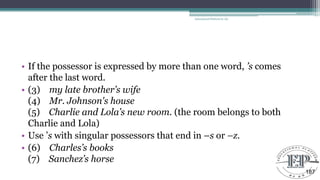

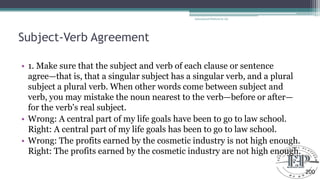

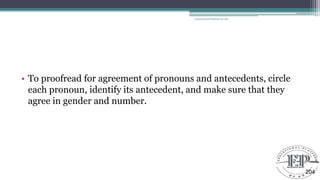

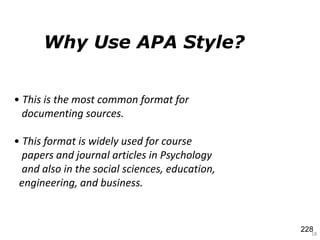

![If group author is easily identified by its abbreviation, you

may abbreviate the name in the second and subsequent

citations:

25

Groups as Authors

Write down corporate author in full every time if the abbreviation is

NOT common.

Examples:

1st citation:

Ministry of Education [MOE], 2001)

Example: (University of Pittsburg, 1998)

Subsequent text citation:

(MOE, 2001)

APA In-Text Citations

235](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/english6thsemesterbsnnoteseducationalplatform-1-230819175239-90f99f70/85/English-6th-Semester-BSN-Notes-Educational-Platform-1-pdf-235-320.jpg)