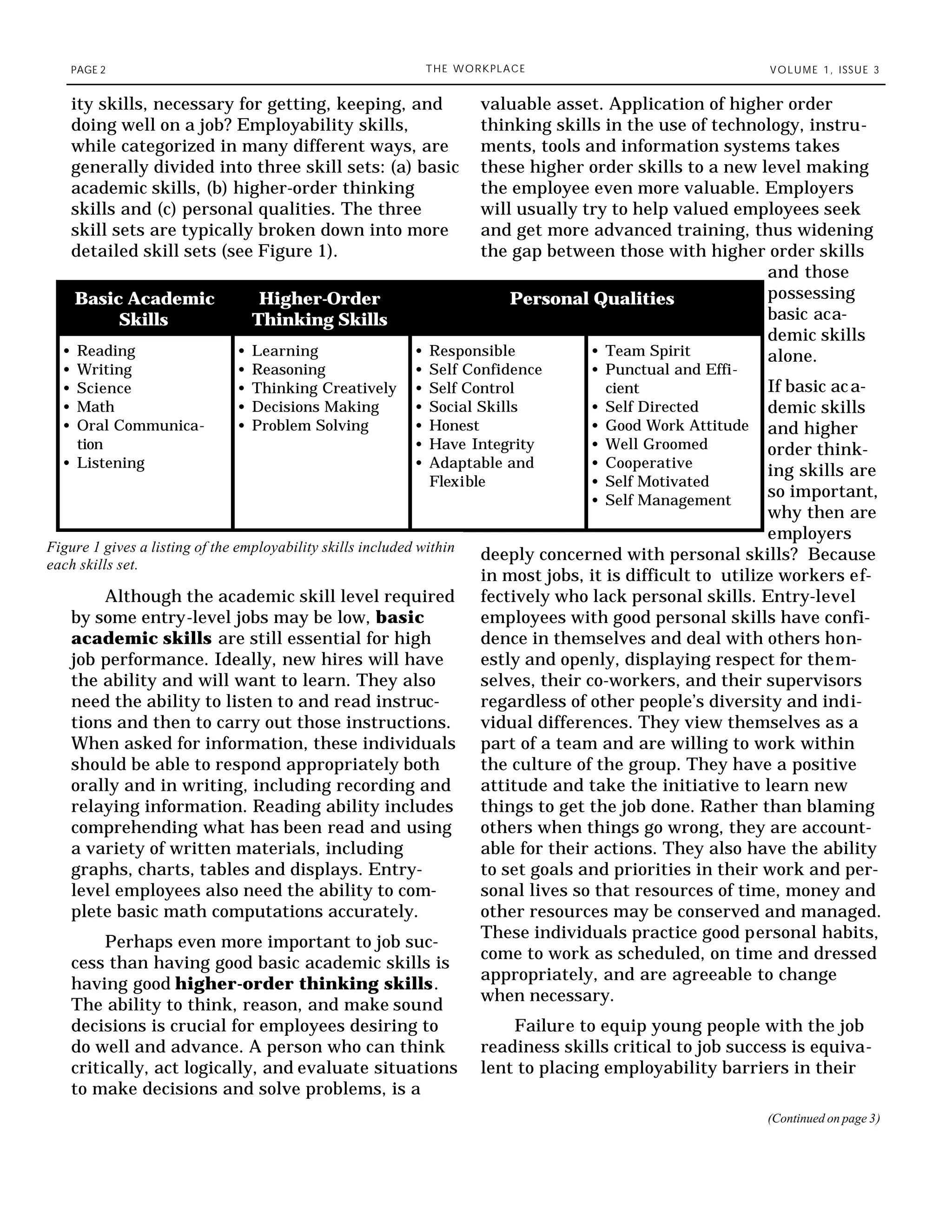

The document discusses employability skills that are important for workers. It notes that employers are concerned with finding workers who possess these skills and may need to provide training. Employability skills include basic academic skills, higher-order thinking skills, and personal qualities. They allow workers to get along with others, make good decisions, and perform well in their jobs. While these skills can be taught, many applicants currently lack them, creating a skills gap problem for employers.