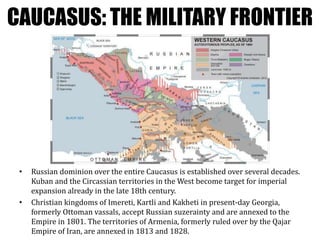

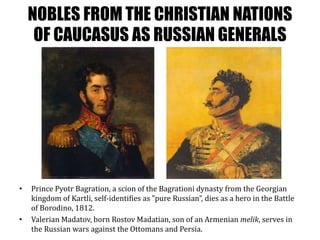

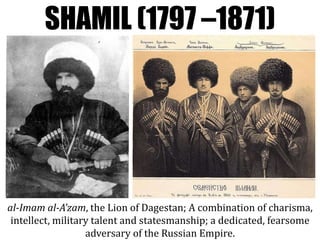

The lecture discusses the complexities of 19th century imperial Russia's expansion and cultural dynamics, focusing on the changing definitions of its diverse populations, particularly non-Christian and indigenous groups. Key points include the integration of local elites into the Russian military hierarchy, systematic imperial expansion in the Caucasus, and the resulting resistance, including the significant figures and events surrounding the insurrection led by Shamil. The lecture also highlights the tragic consequences of conquest, including the Circassian genocide and the forced migration of the Crimean Tatars.