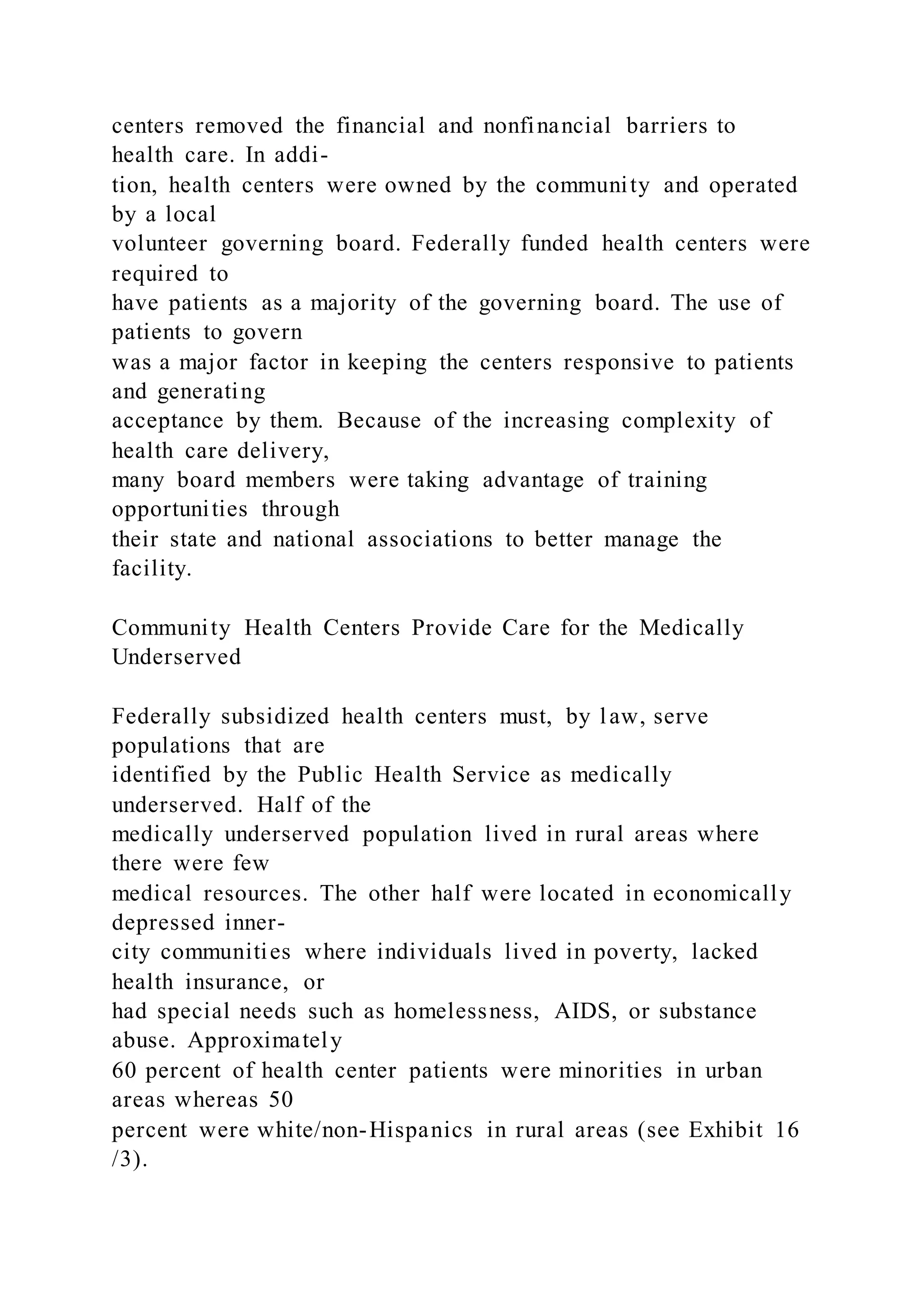

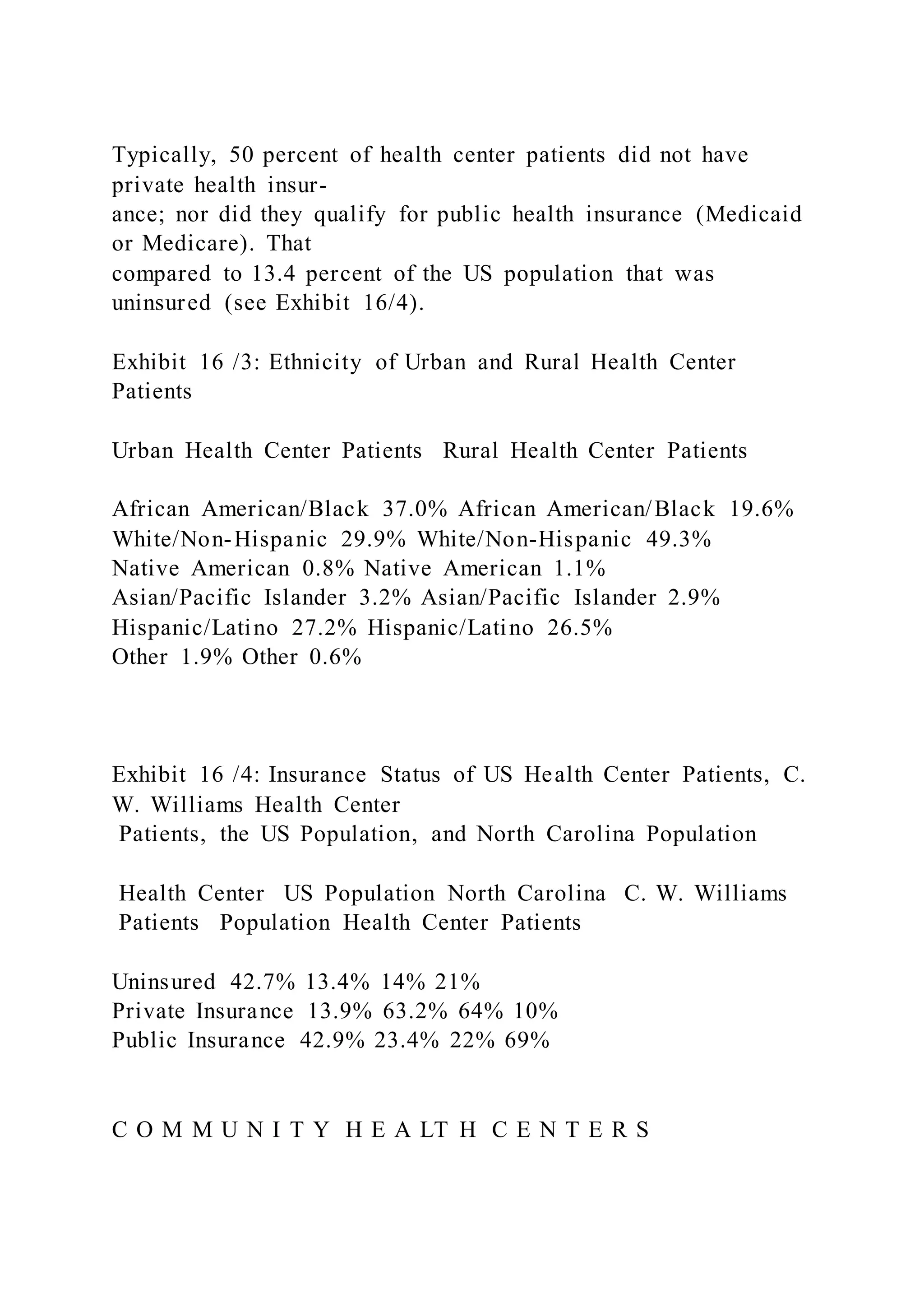

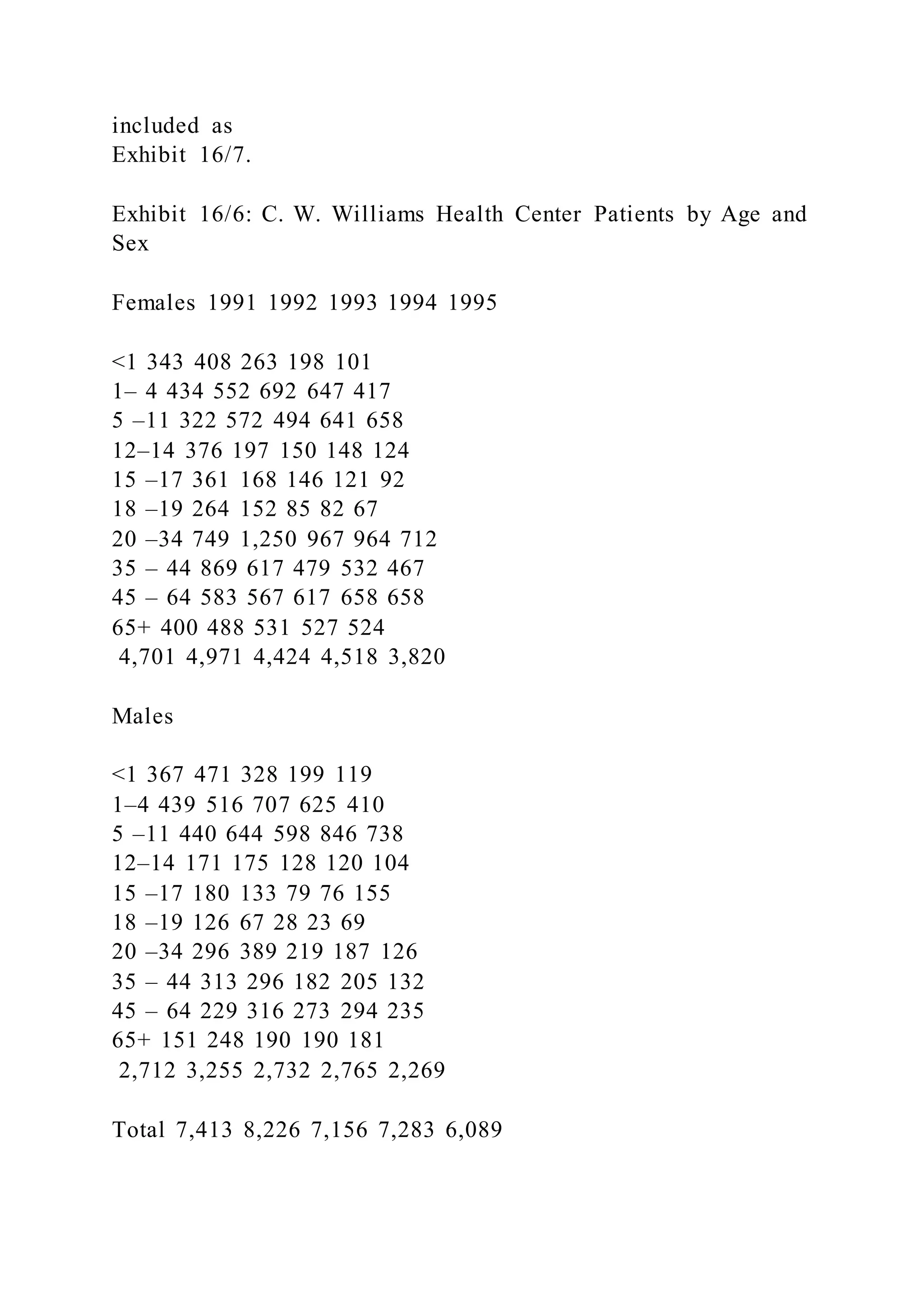

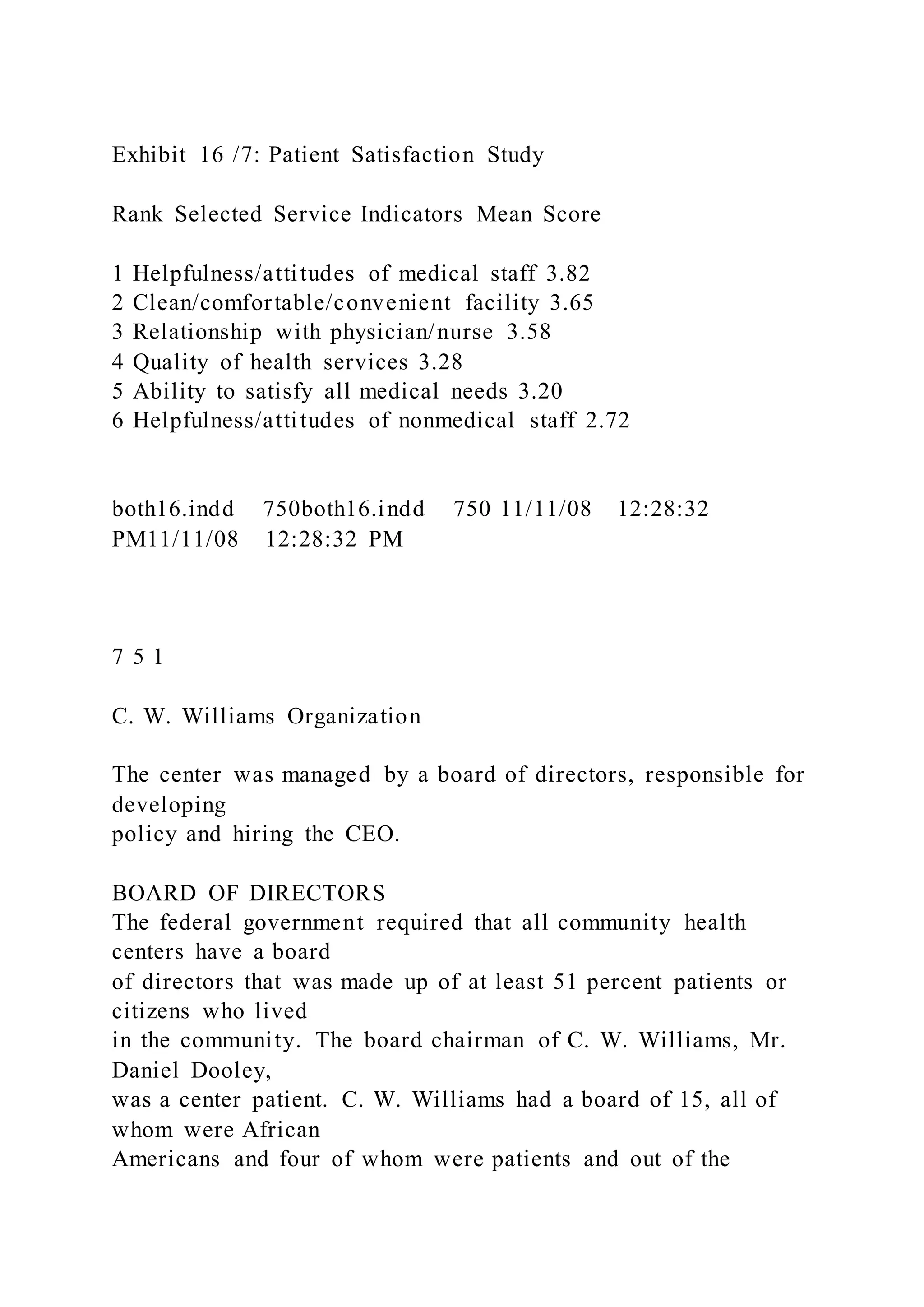

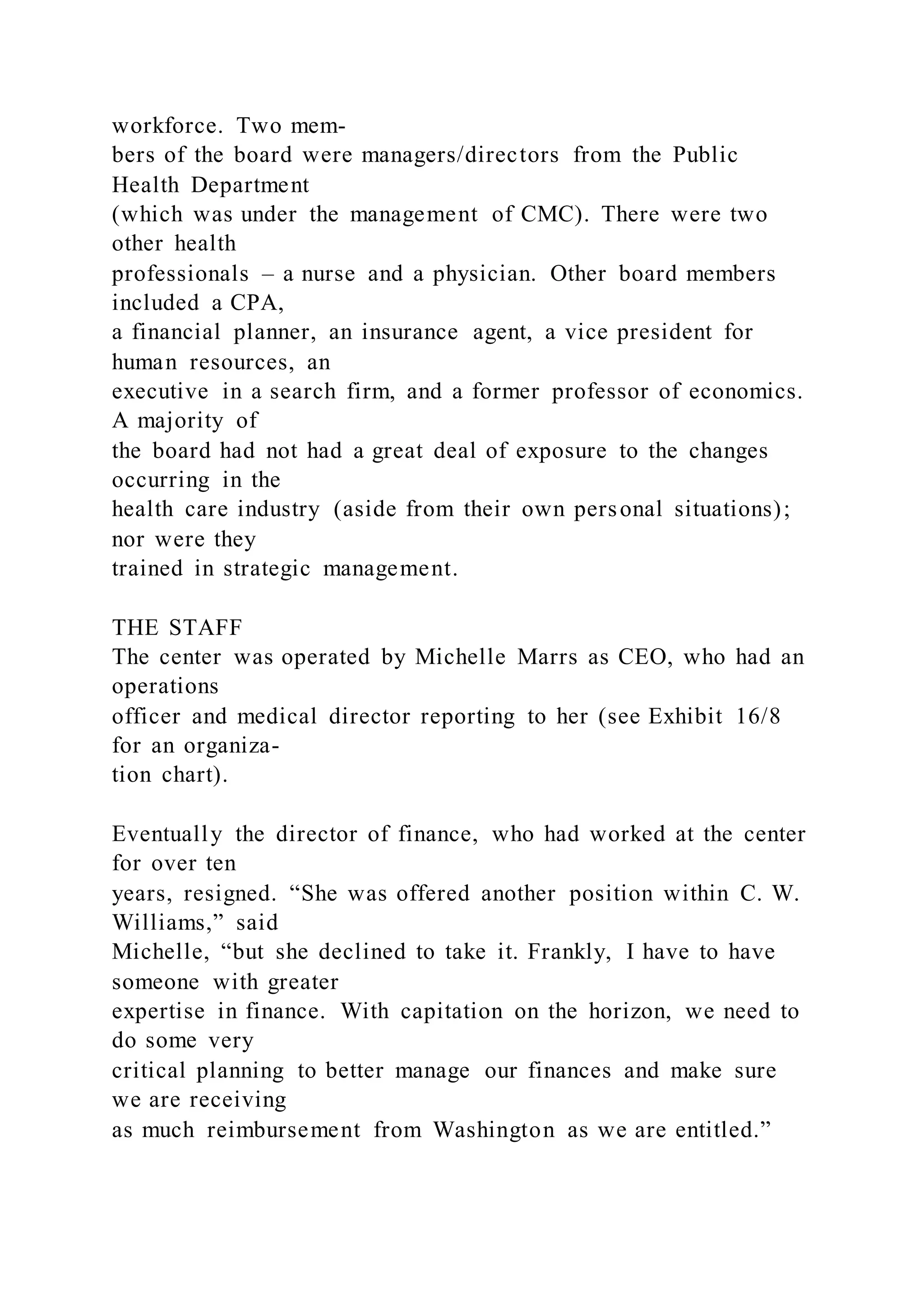

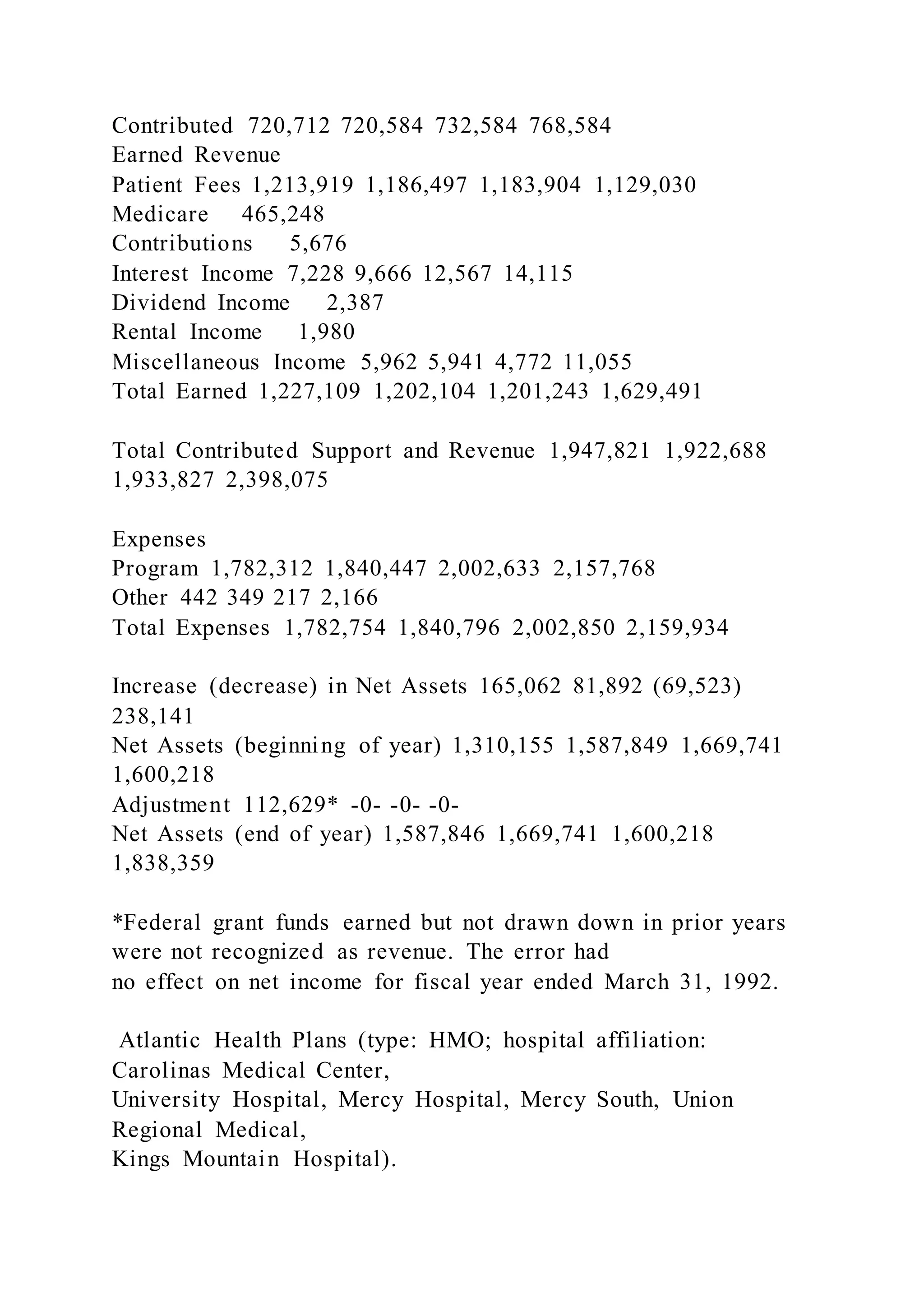

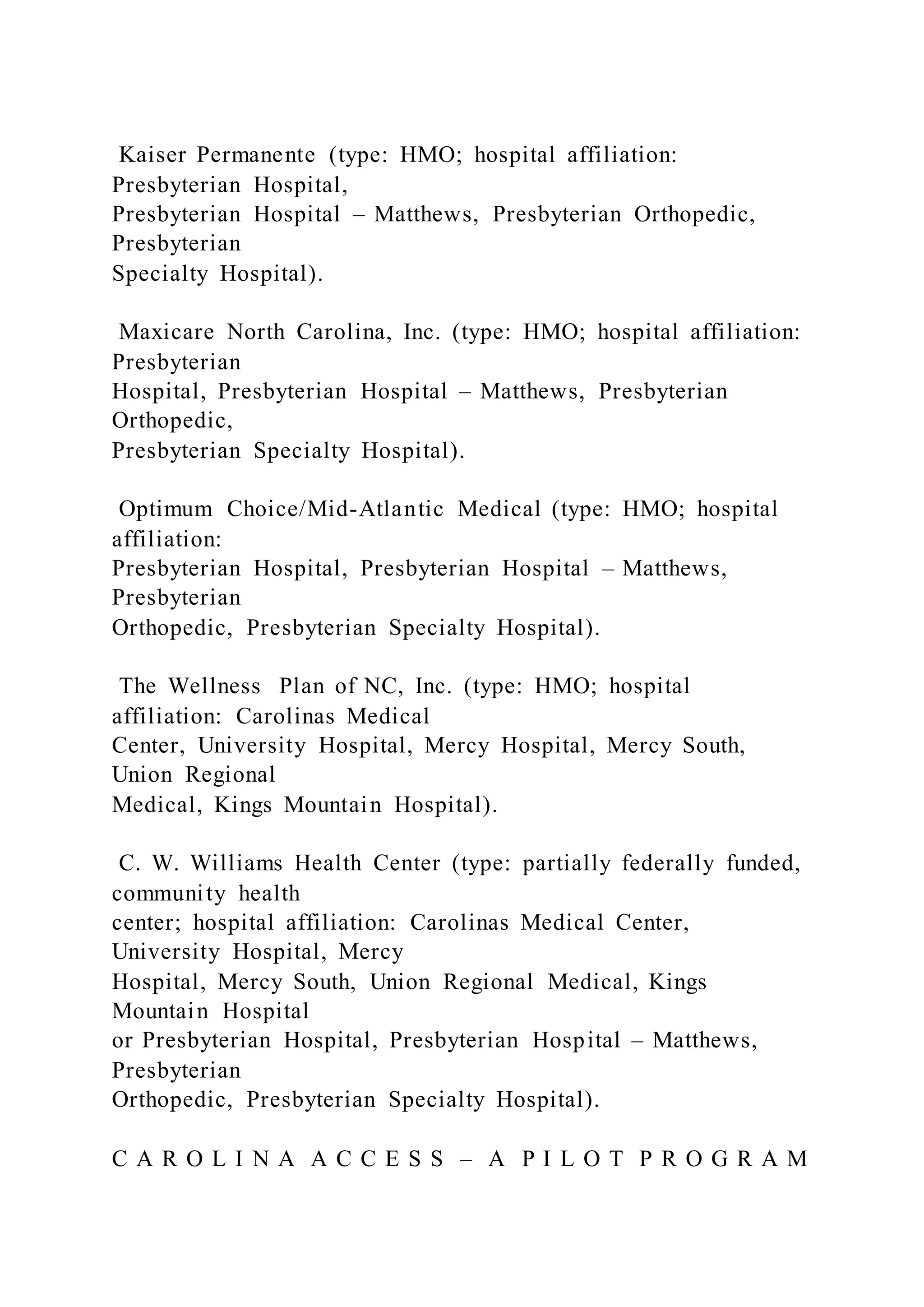

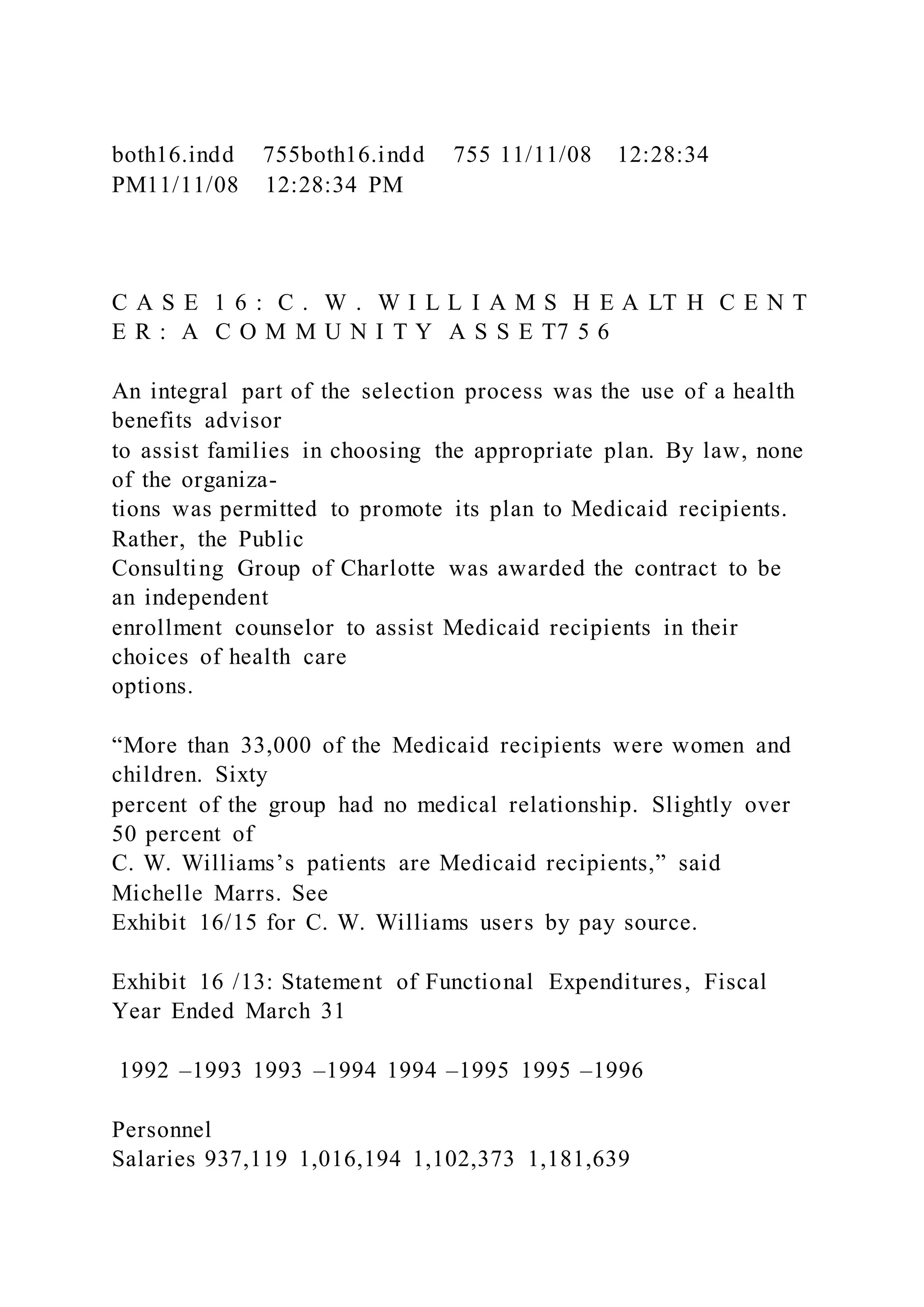

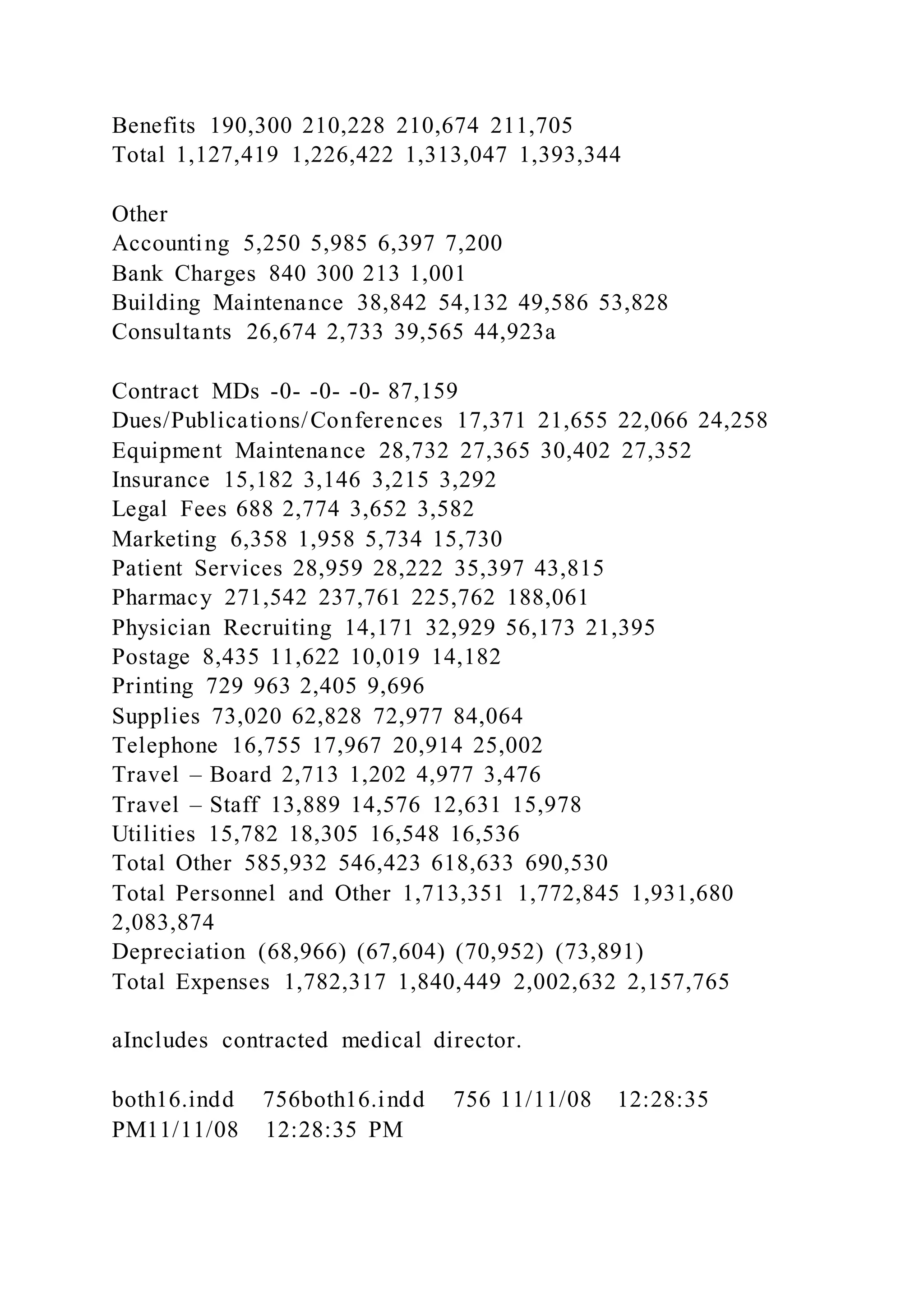

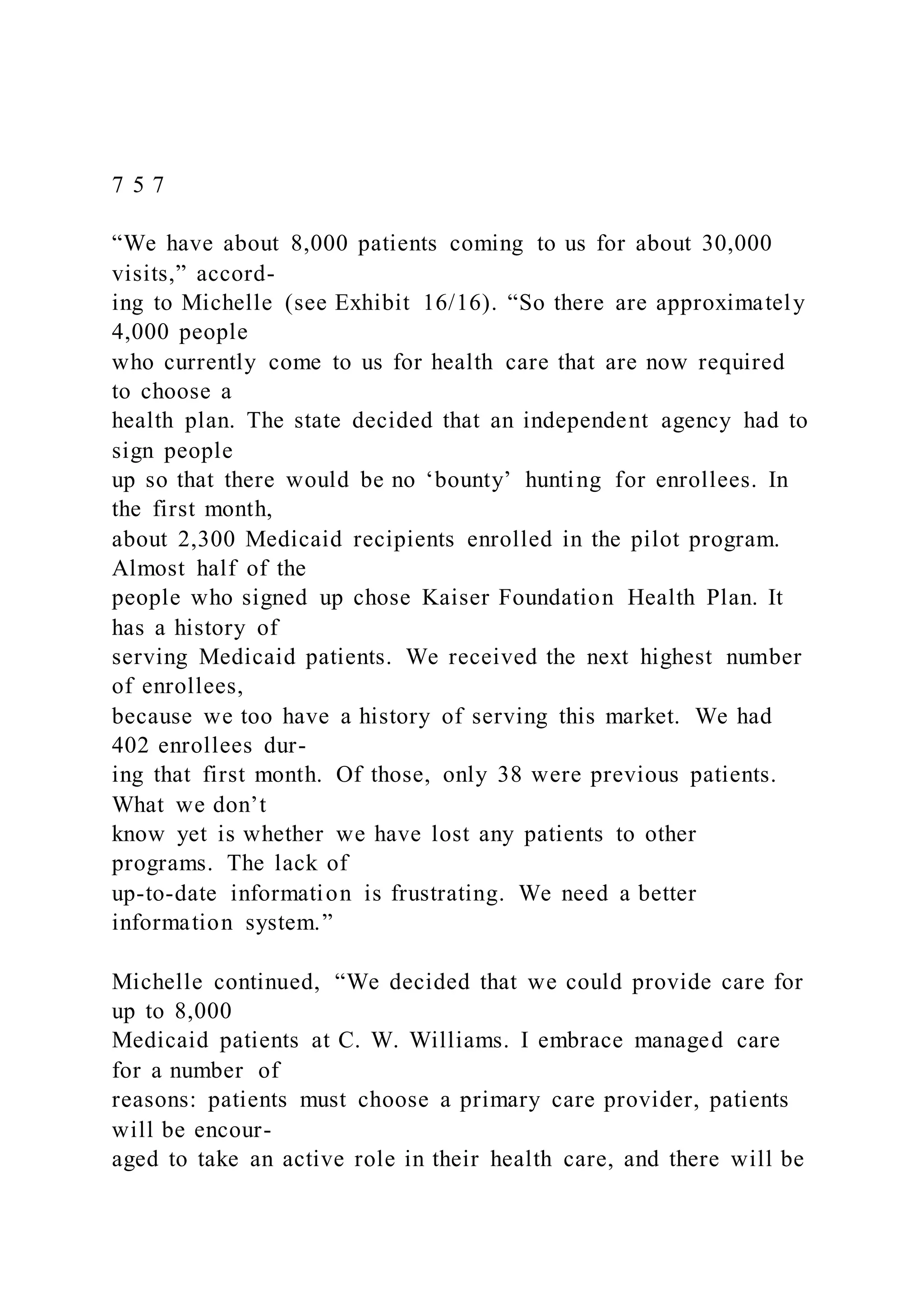

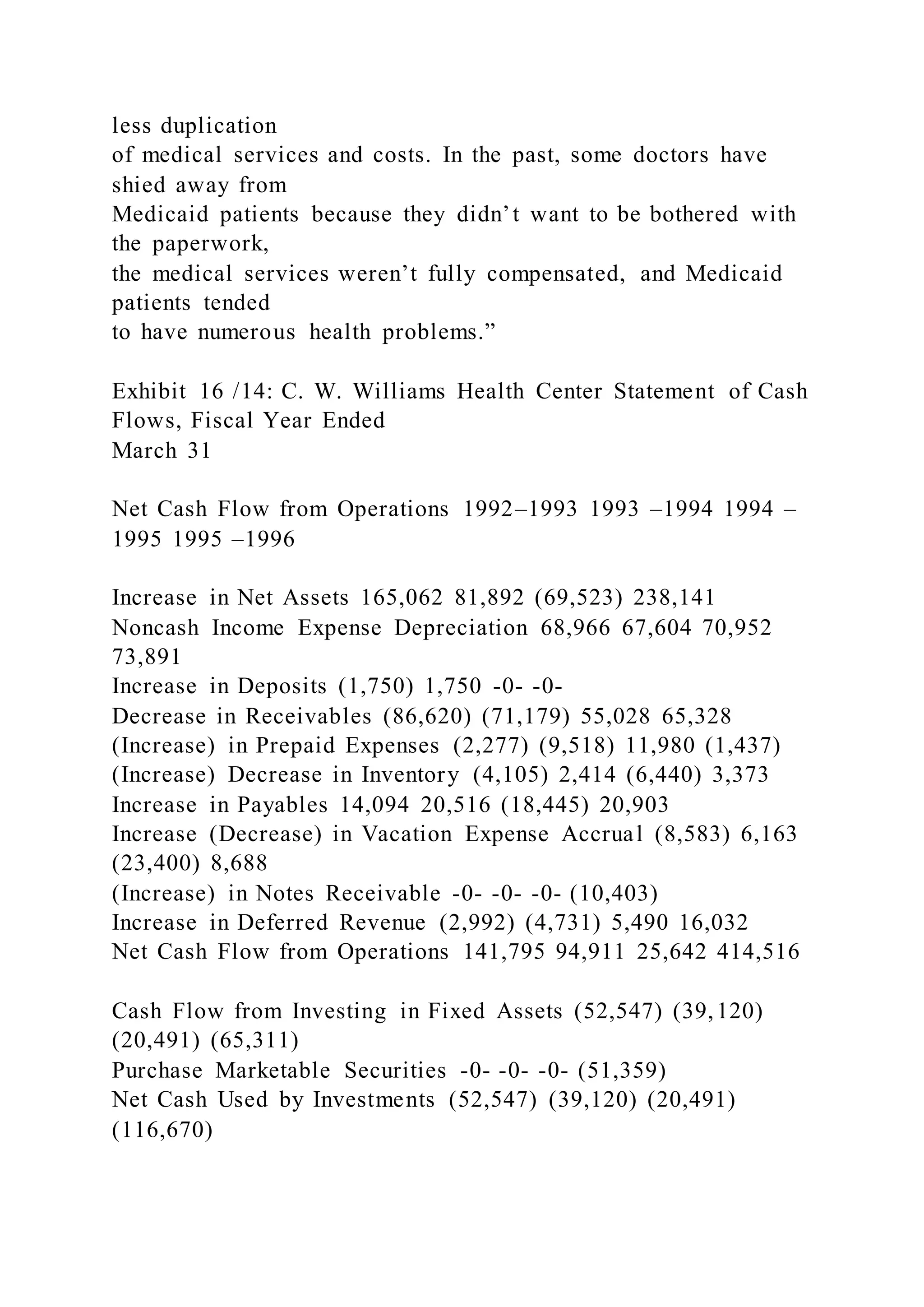

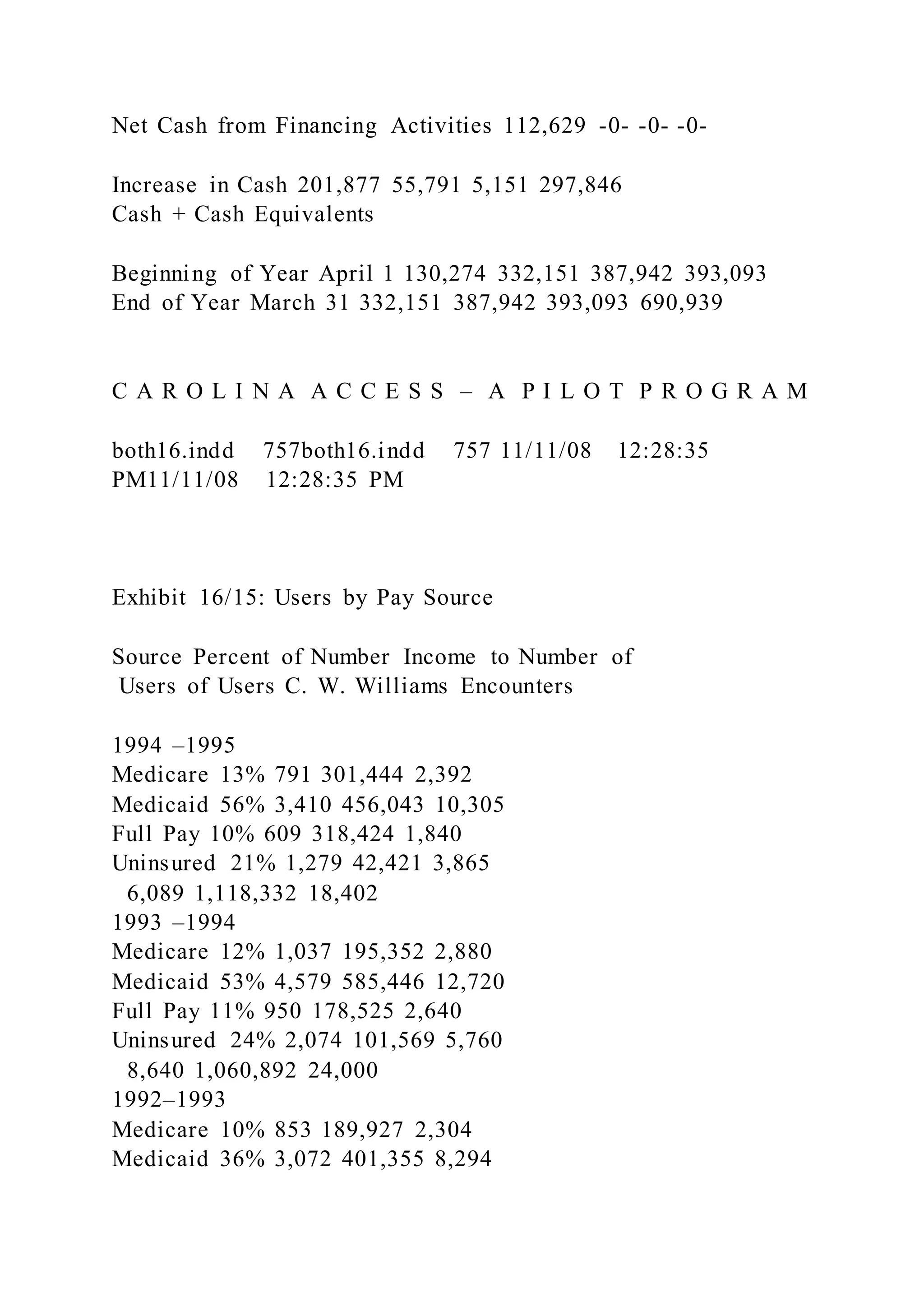

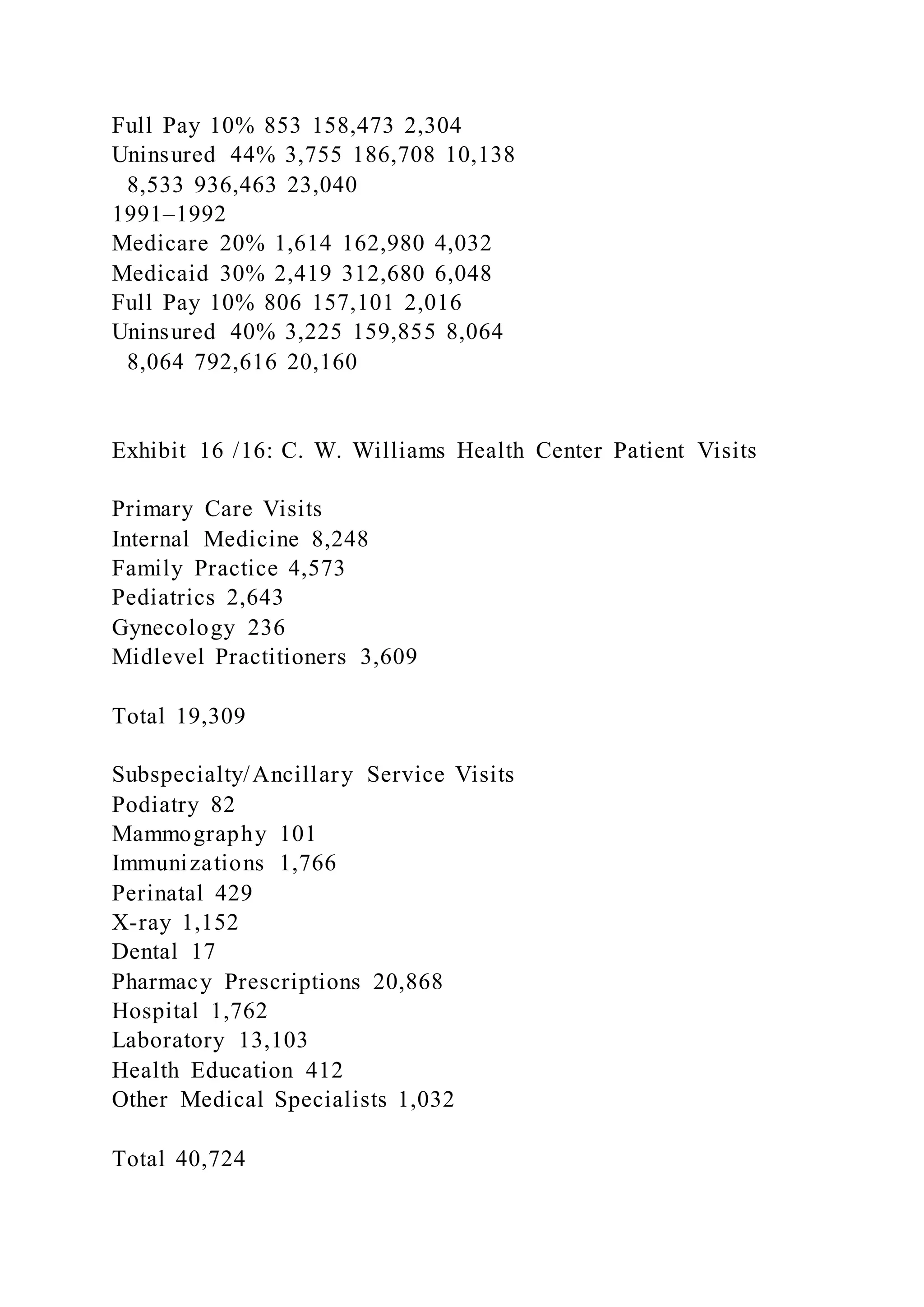

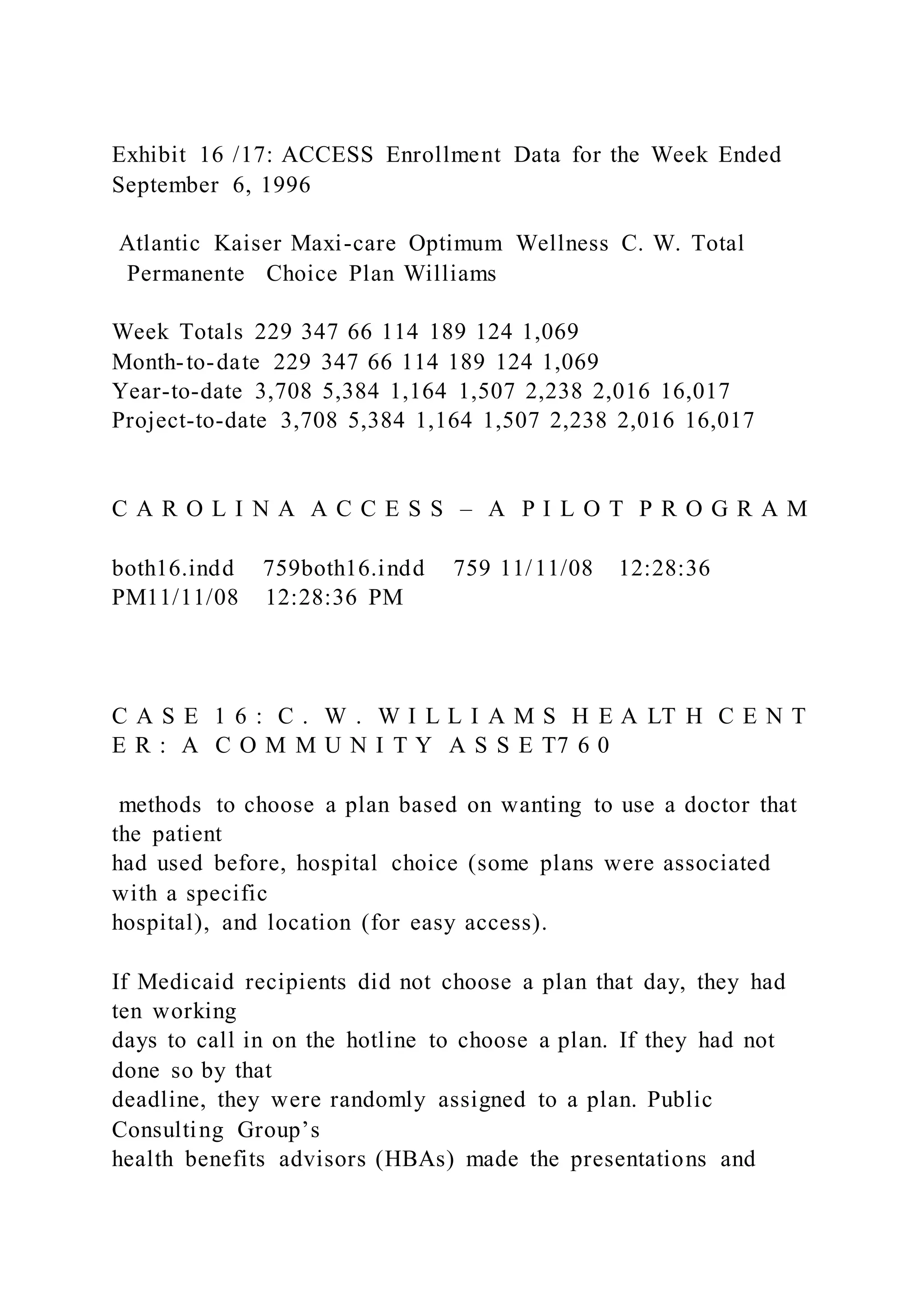

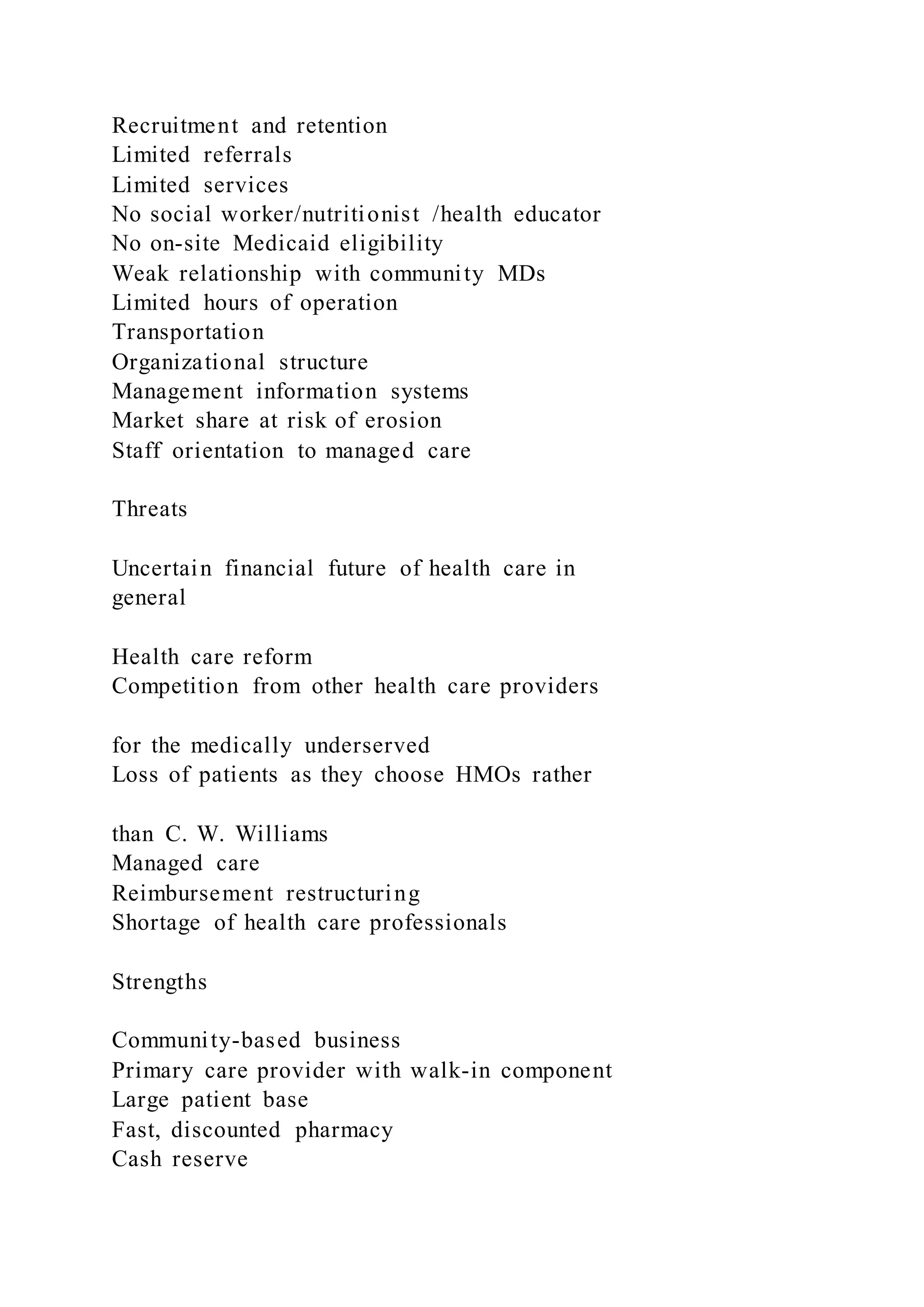

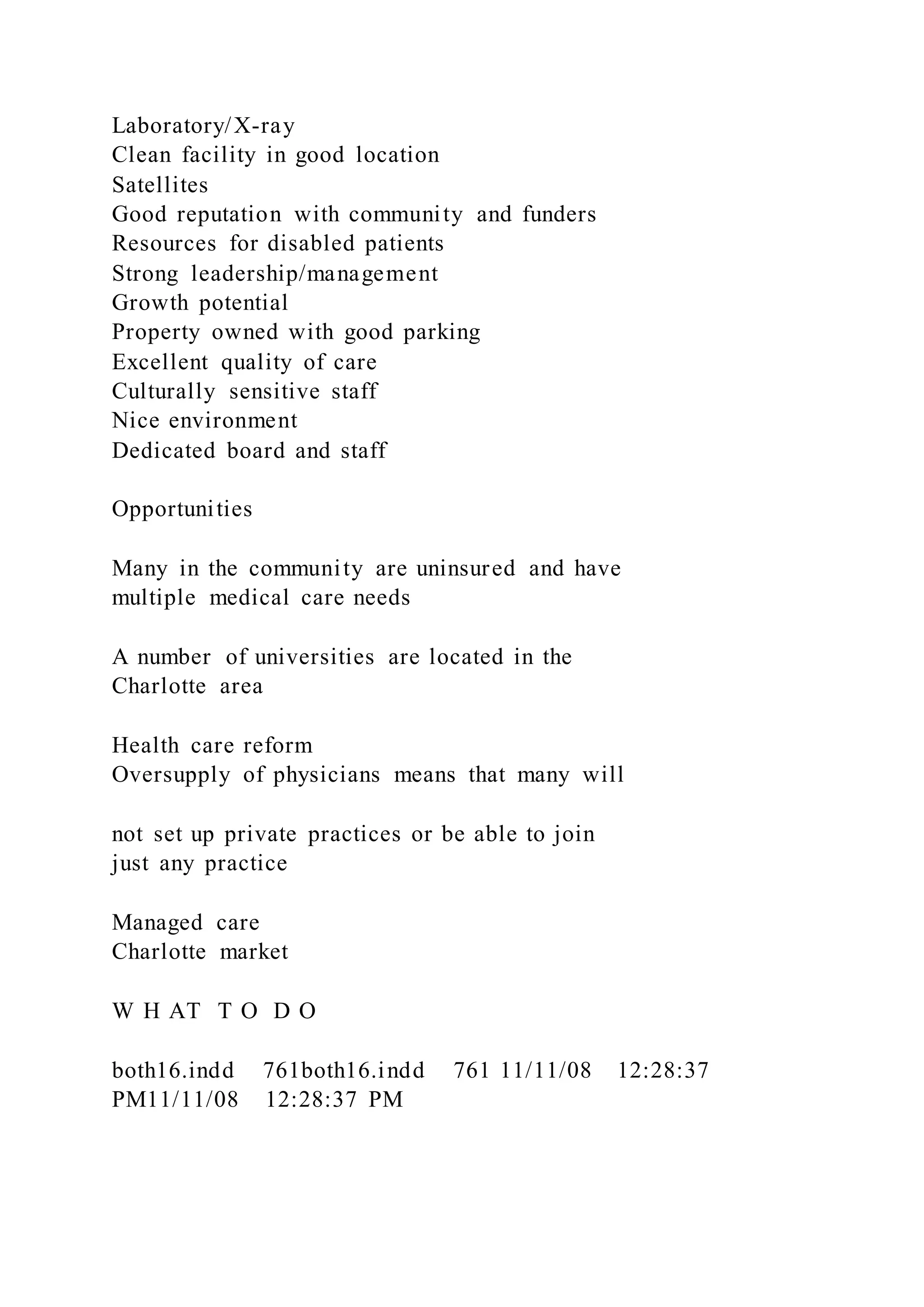

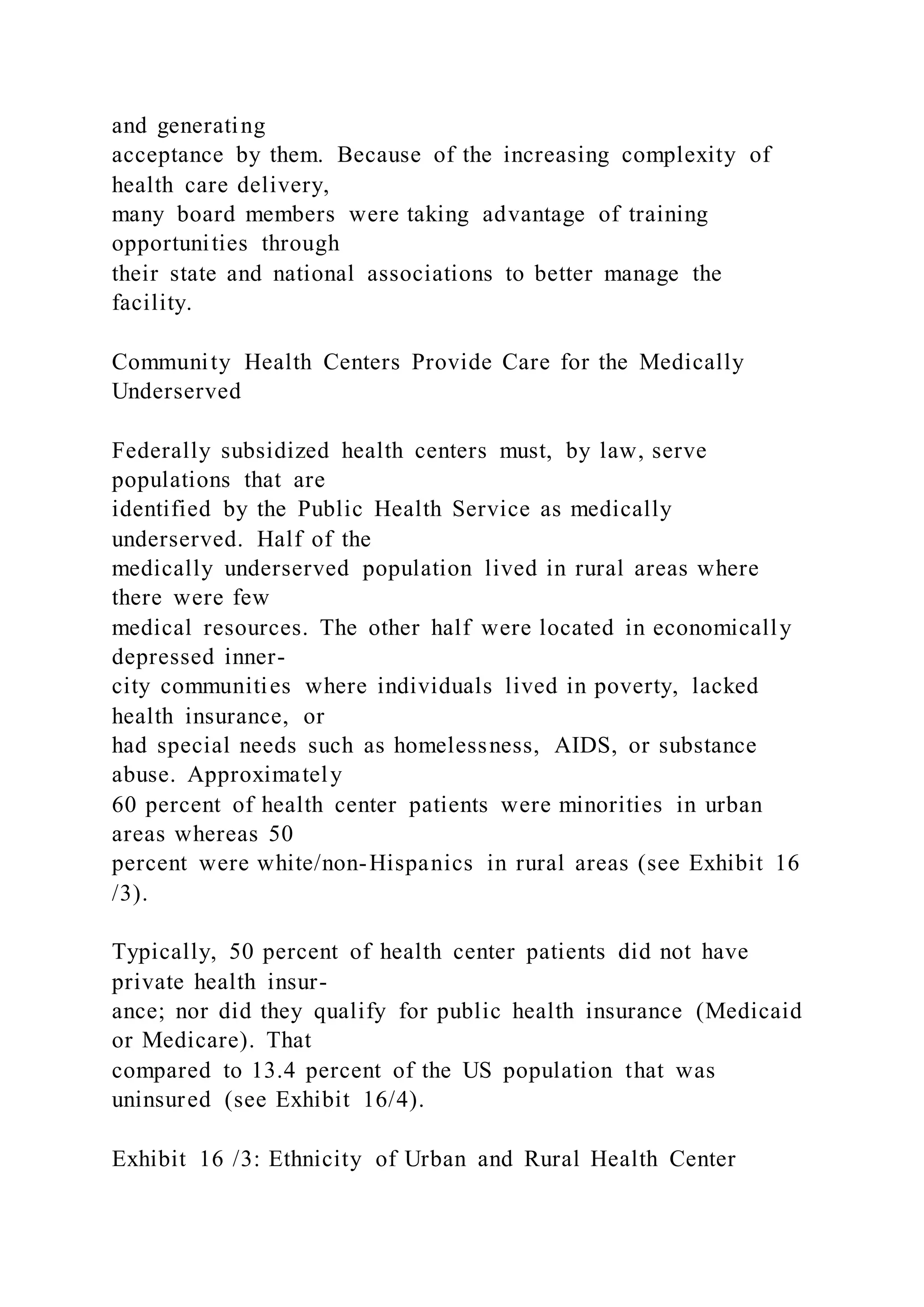

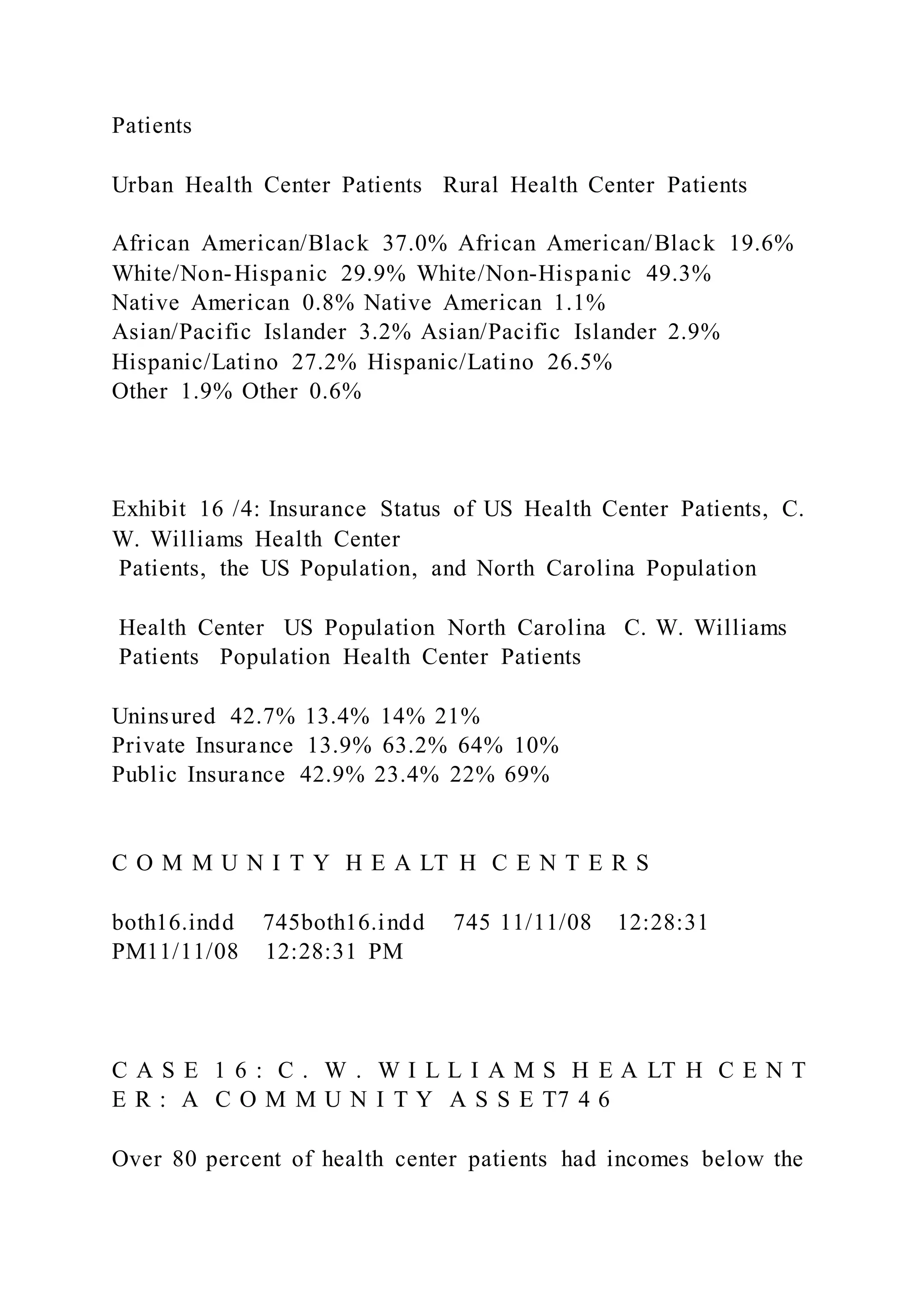

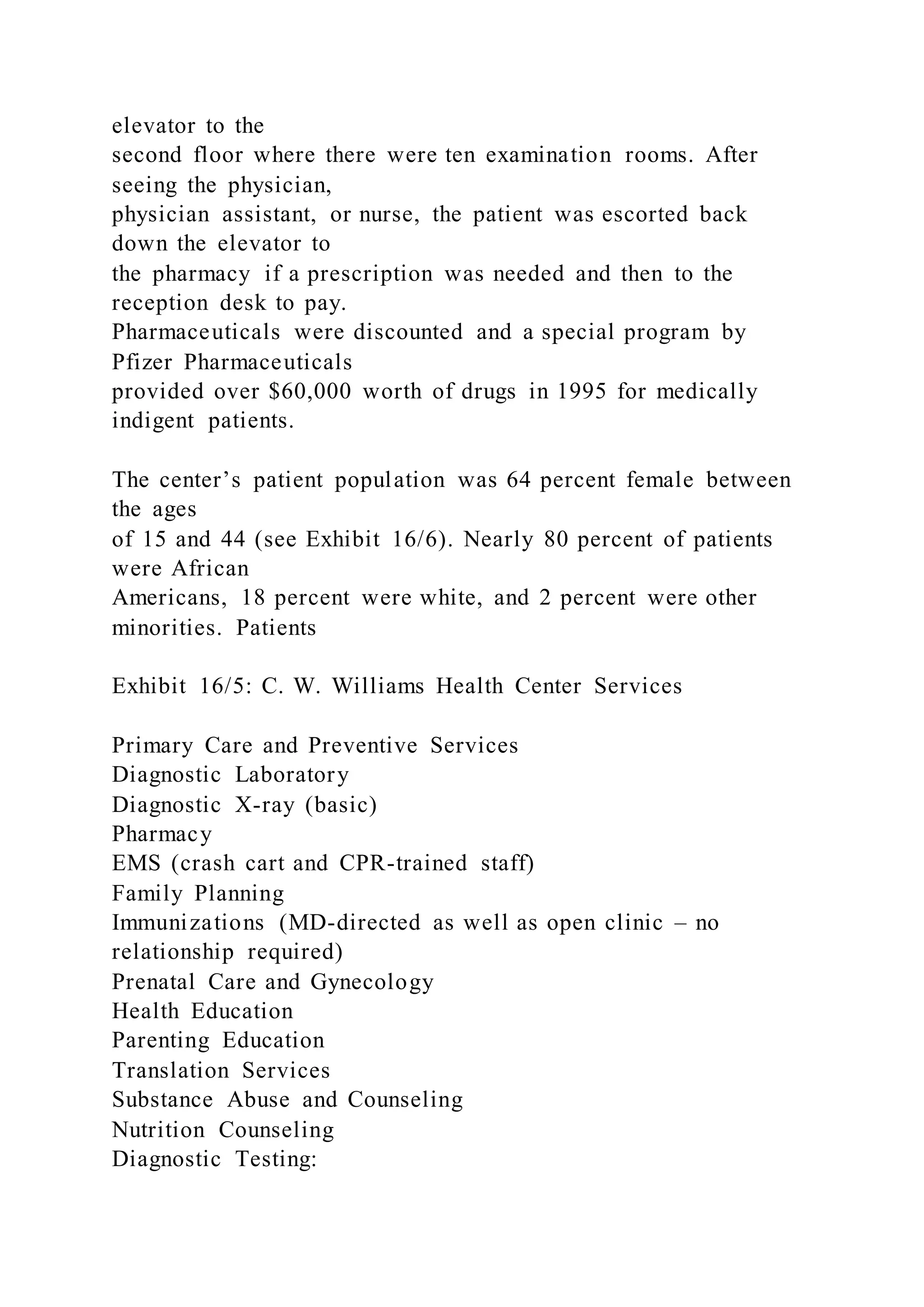

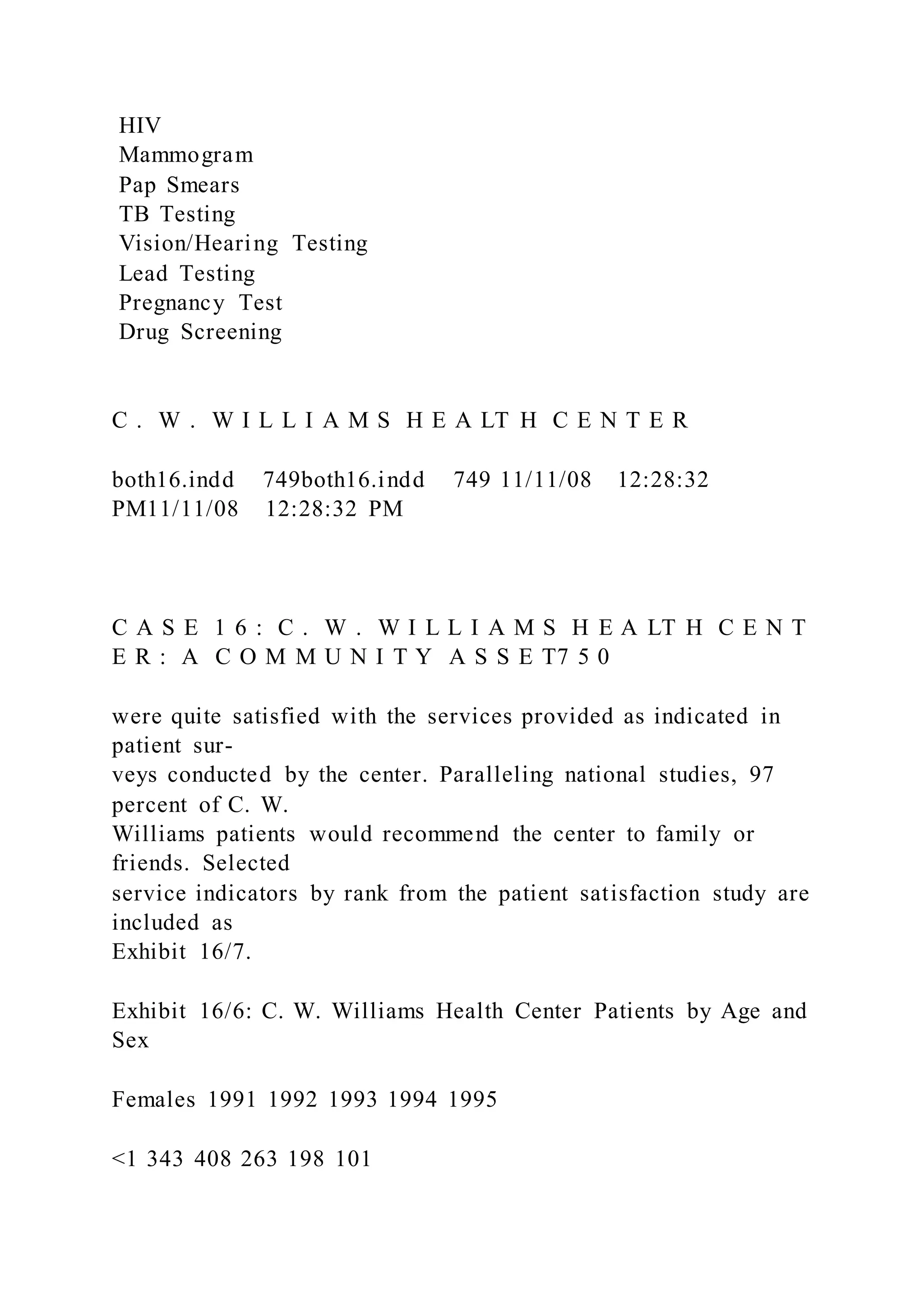

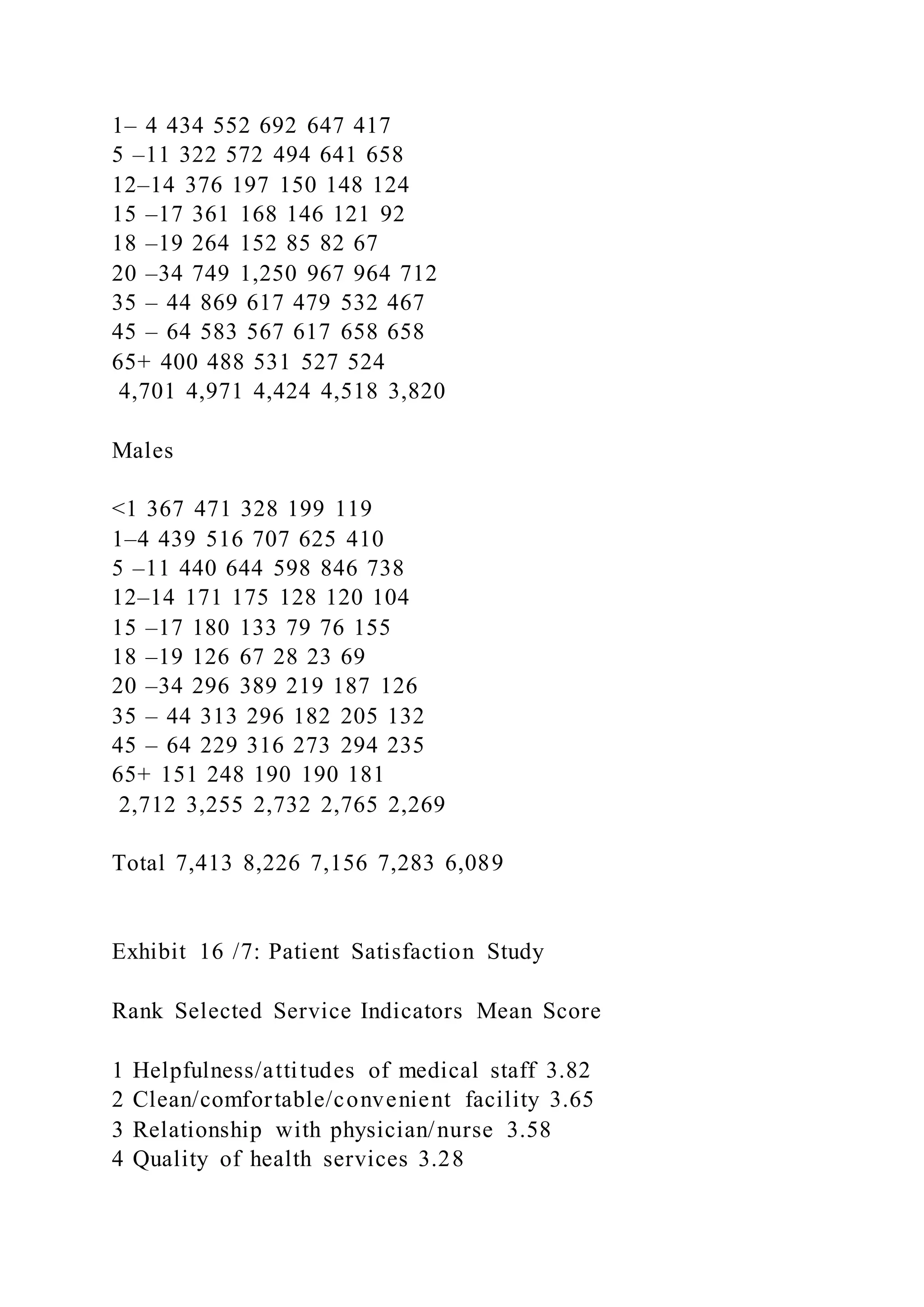

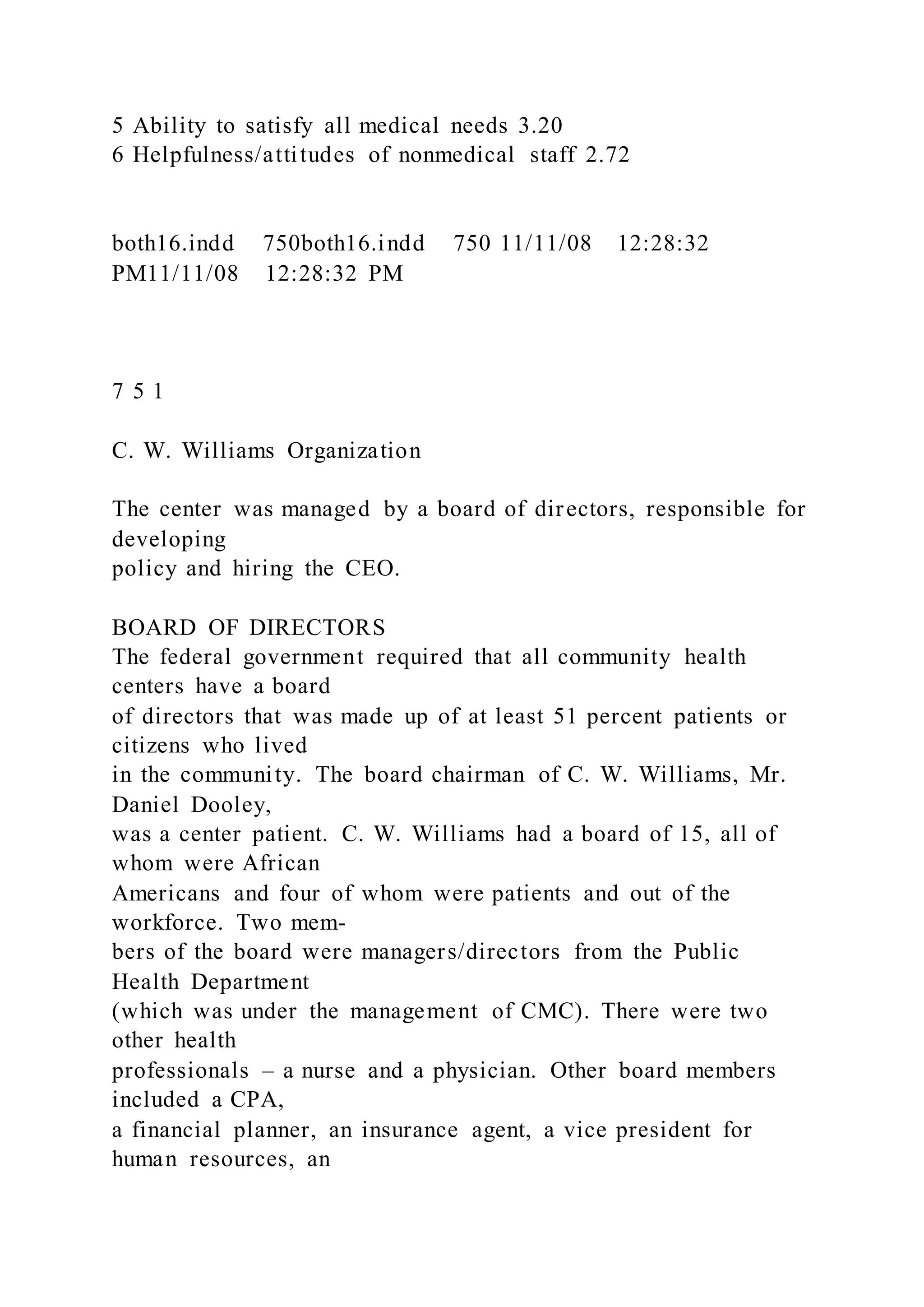

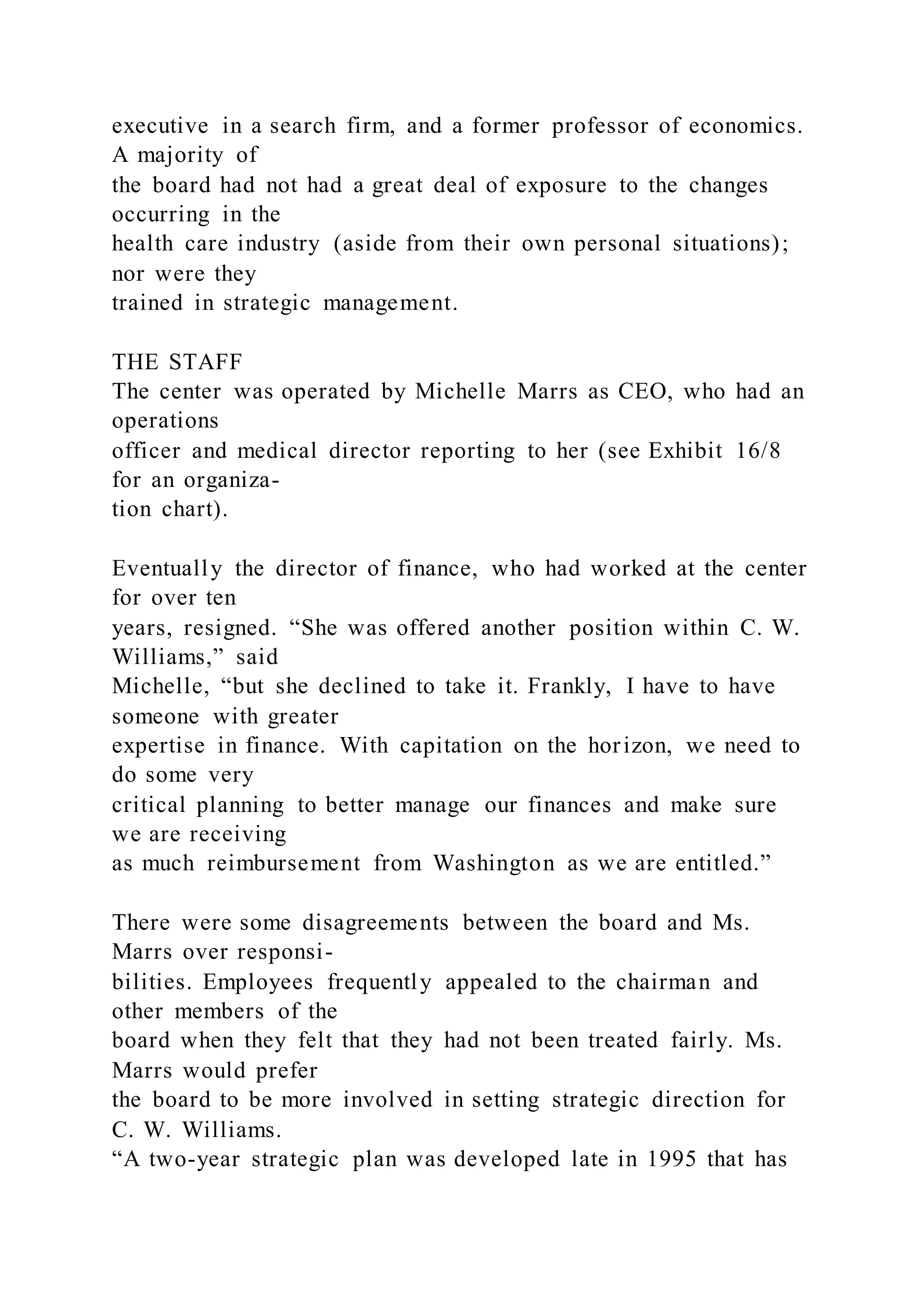

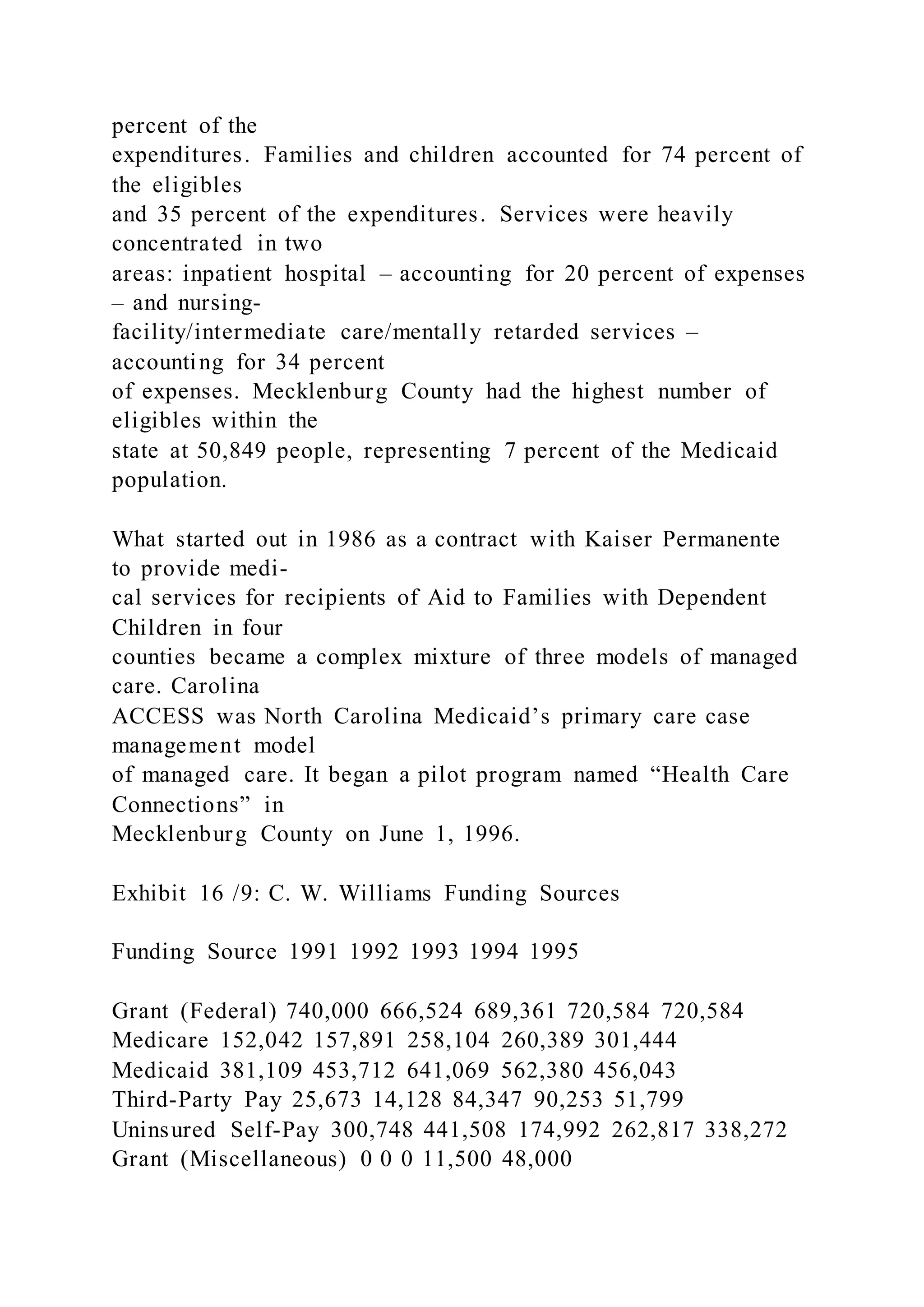

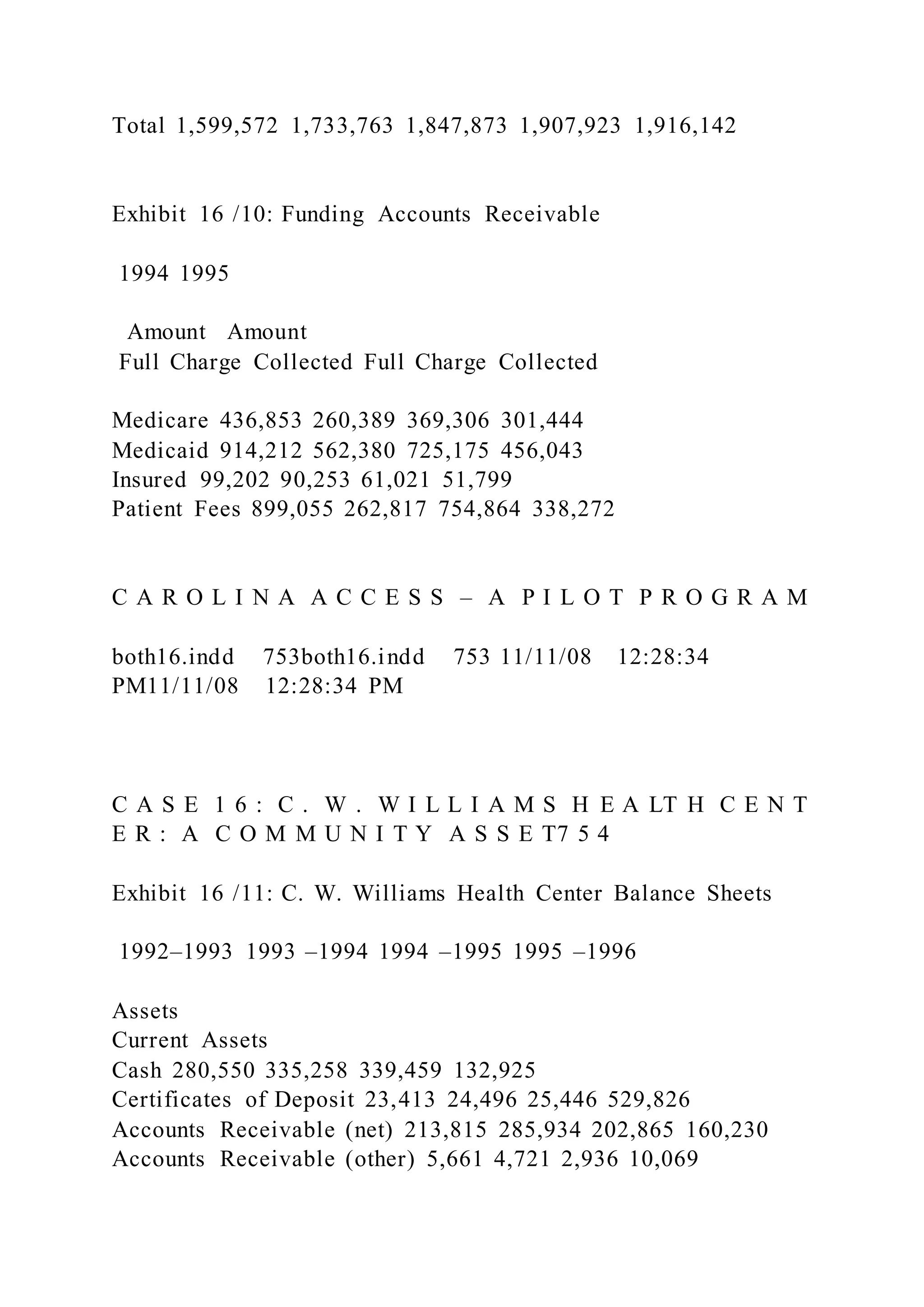

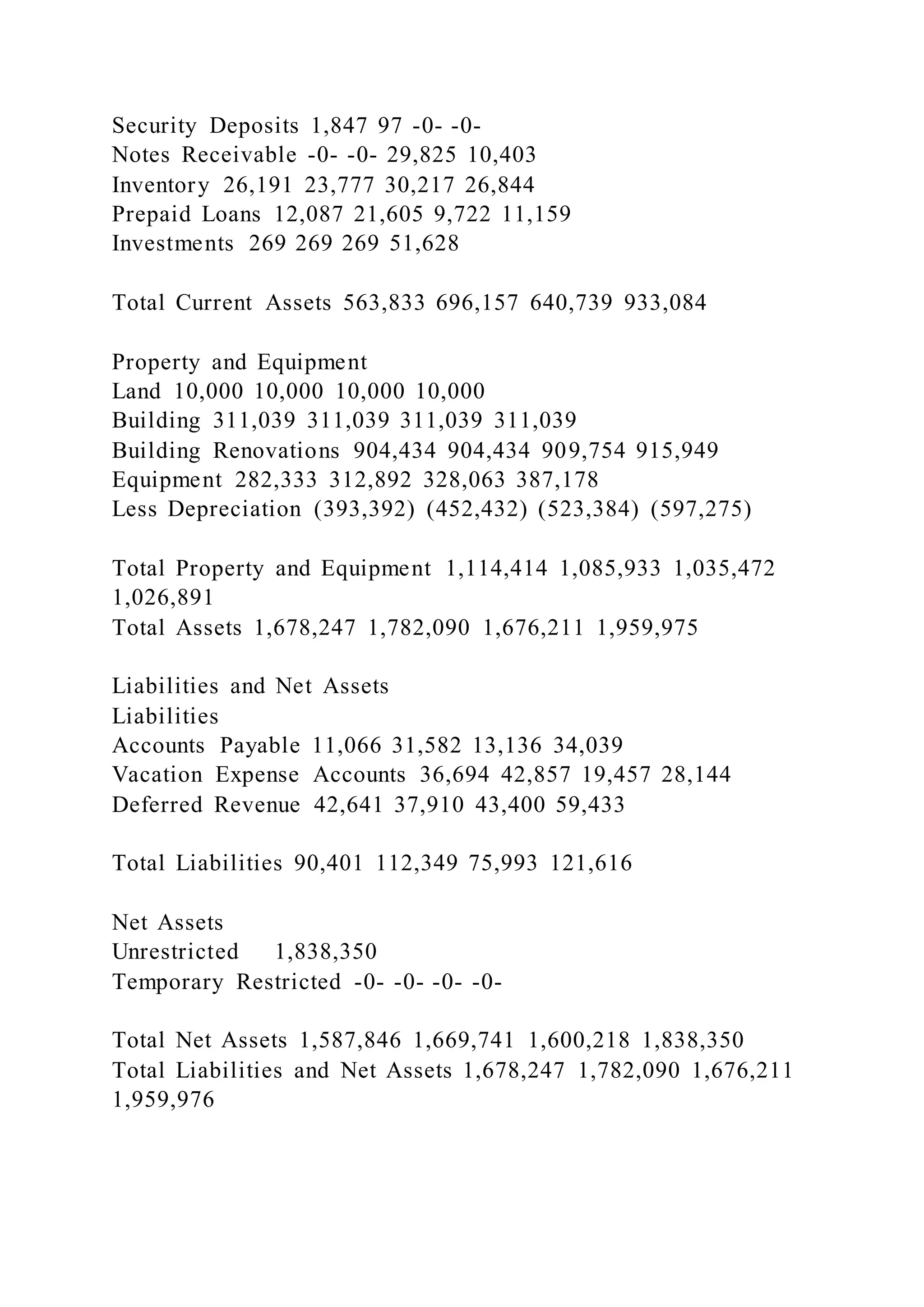

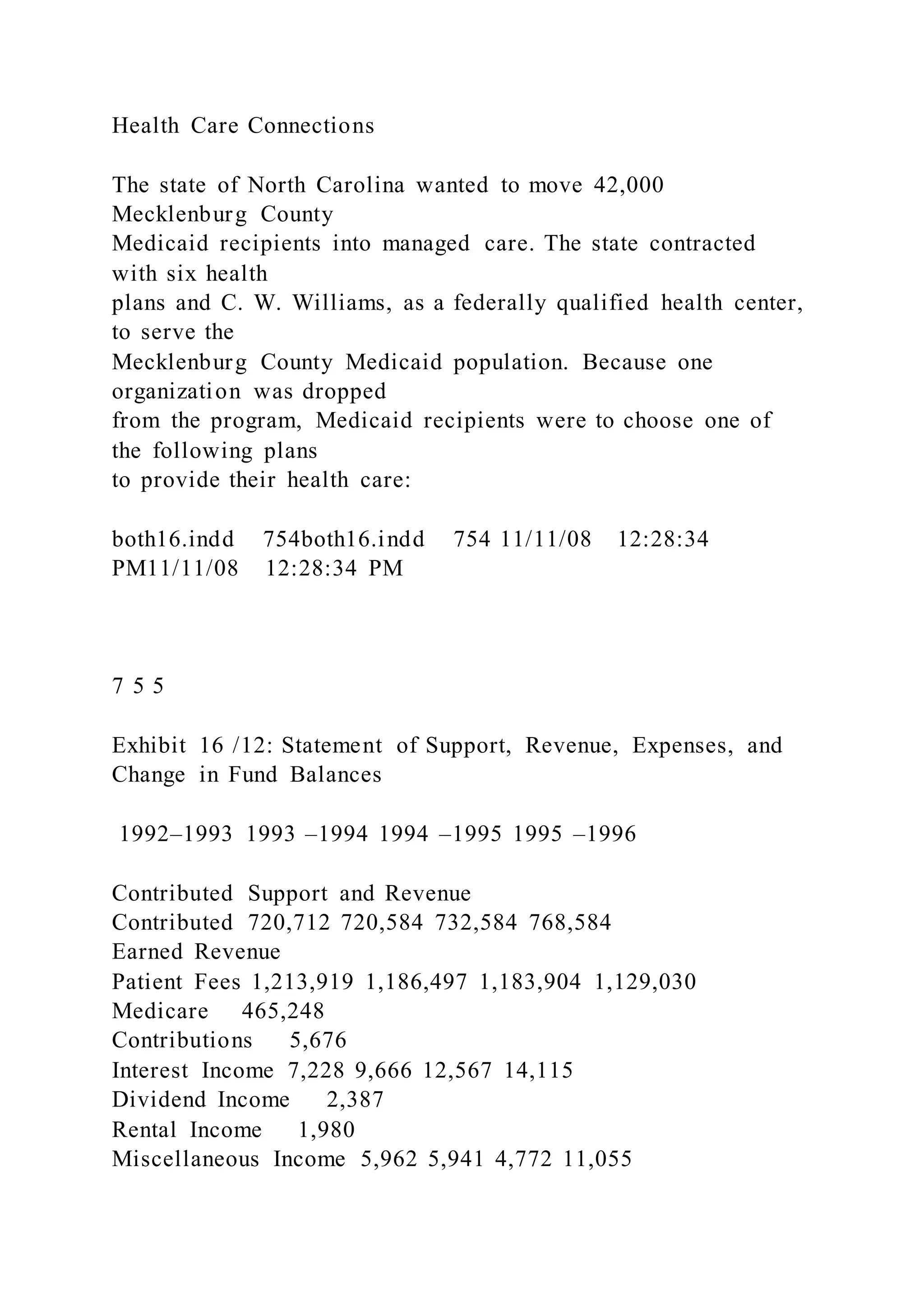

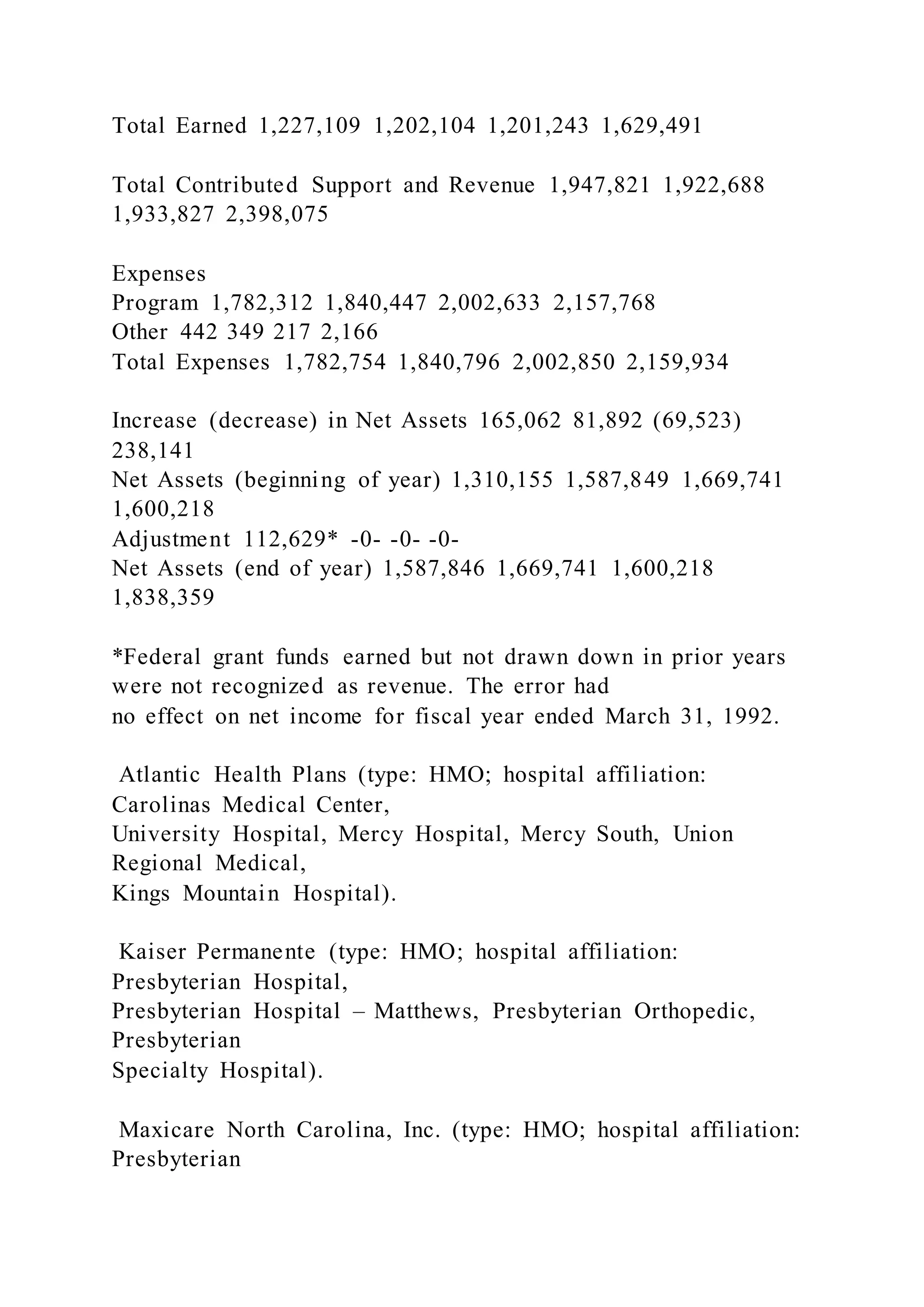

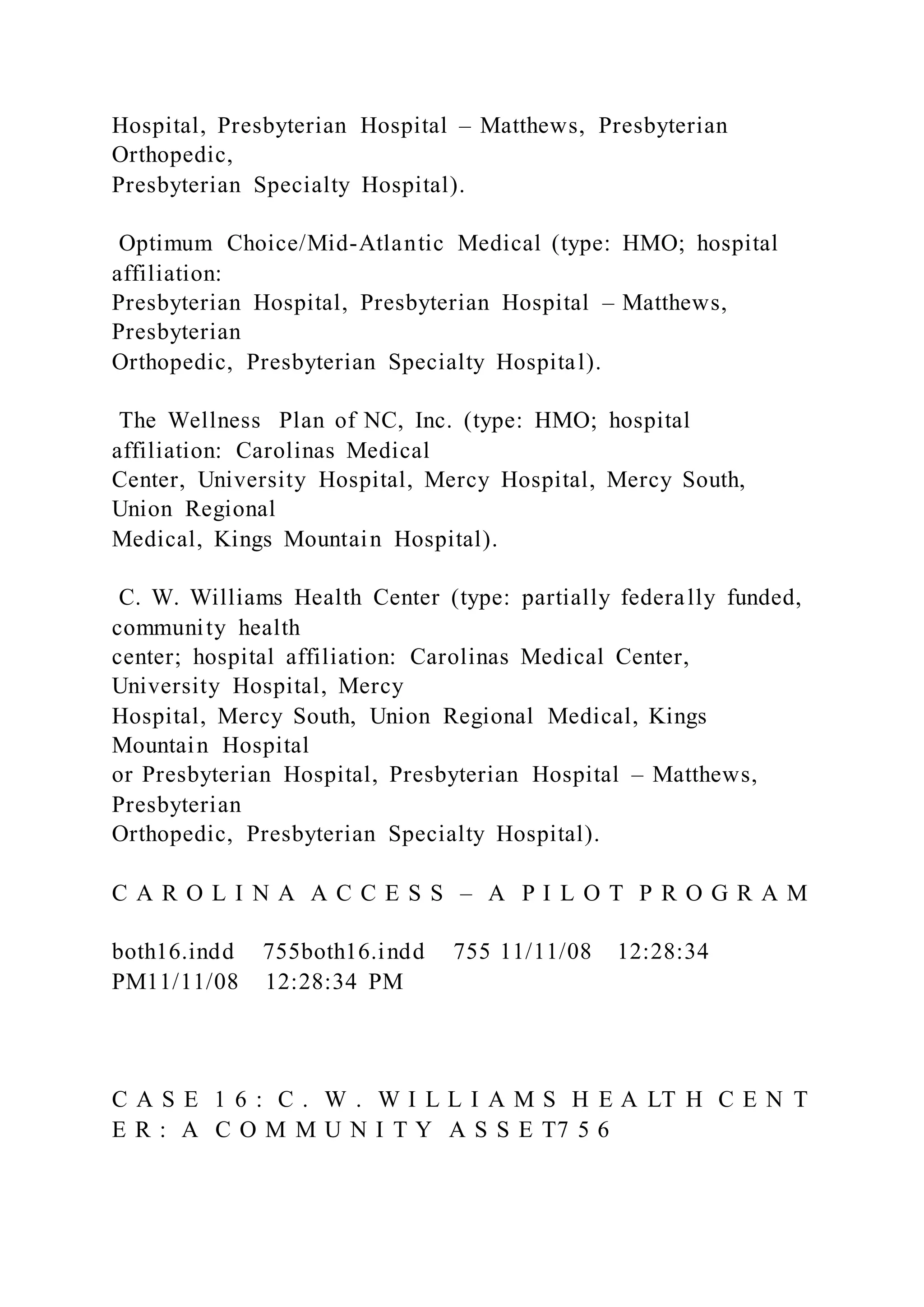

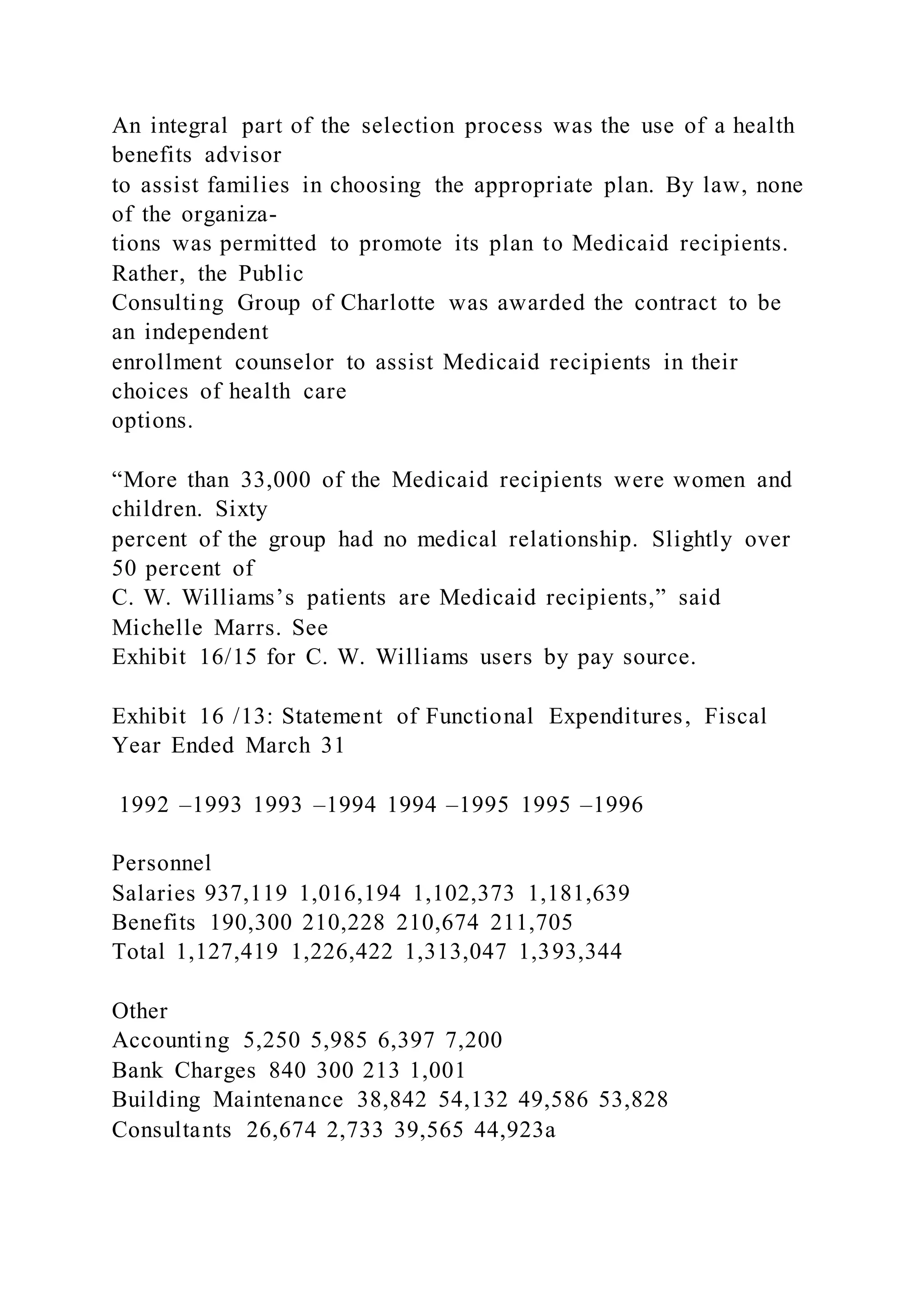

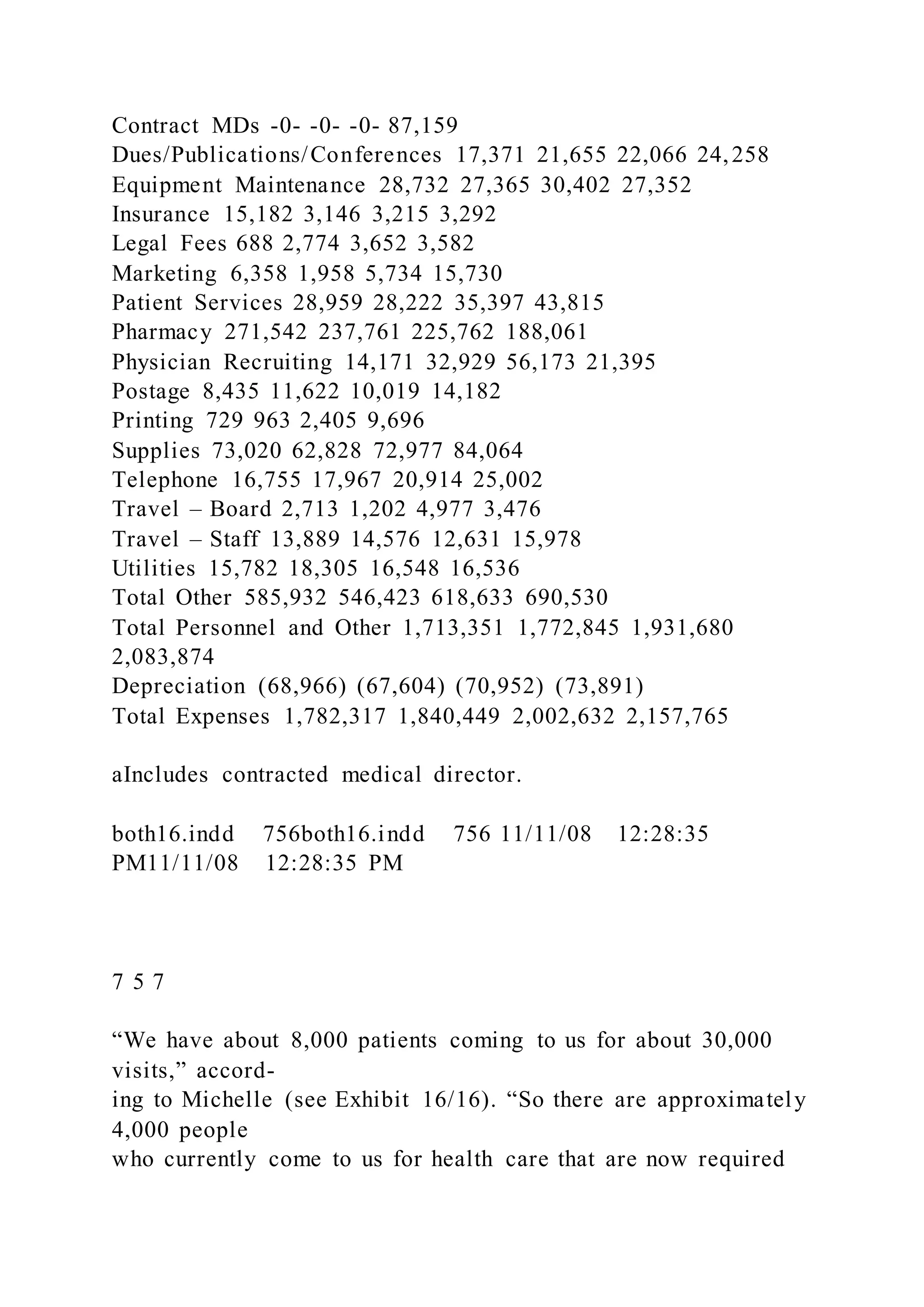

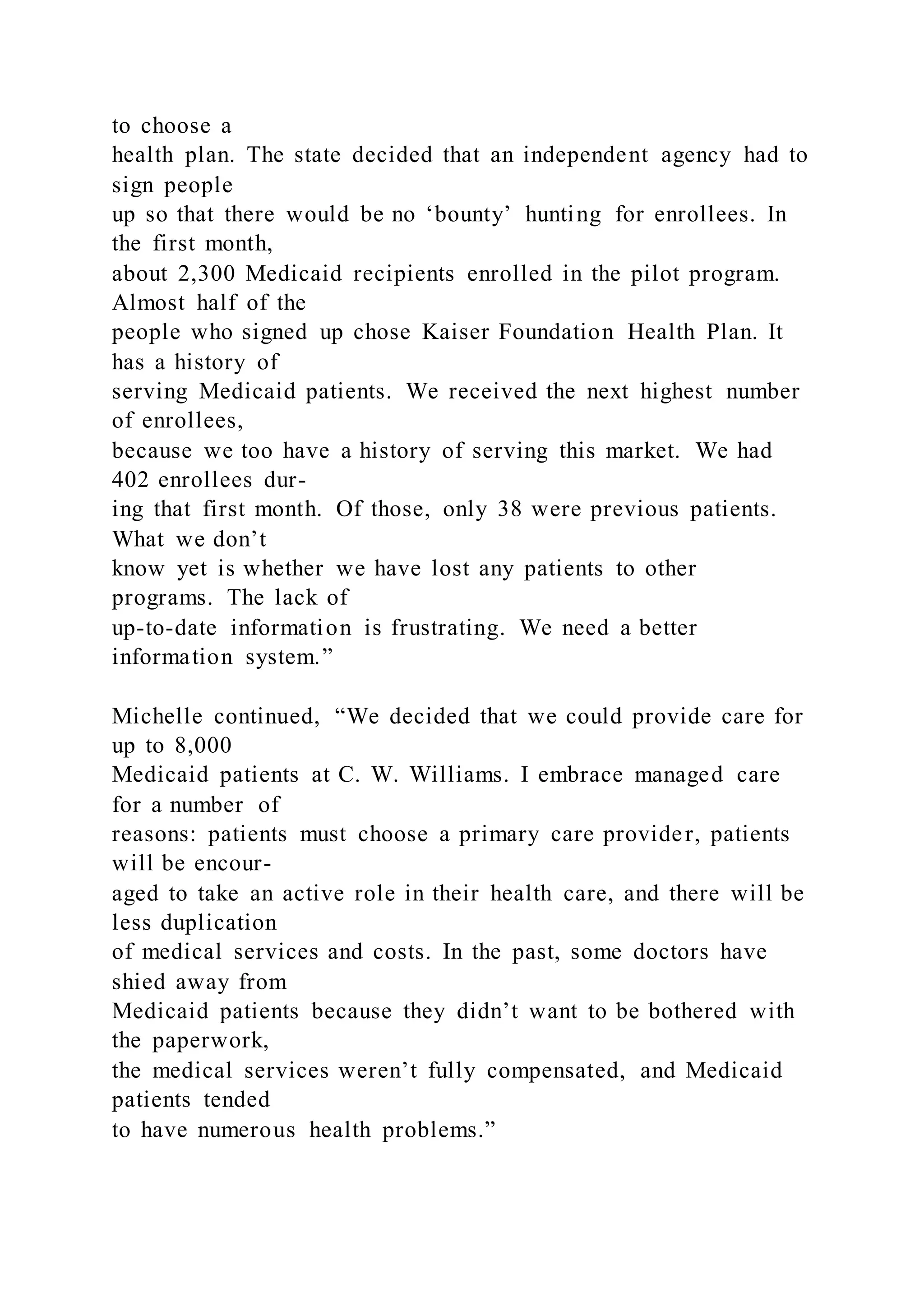

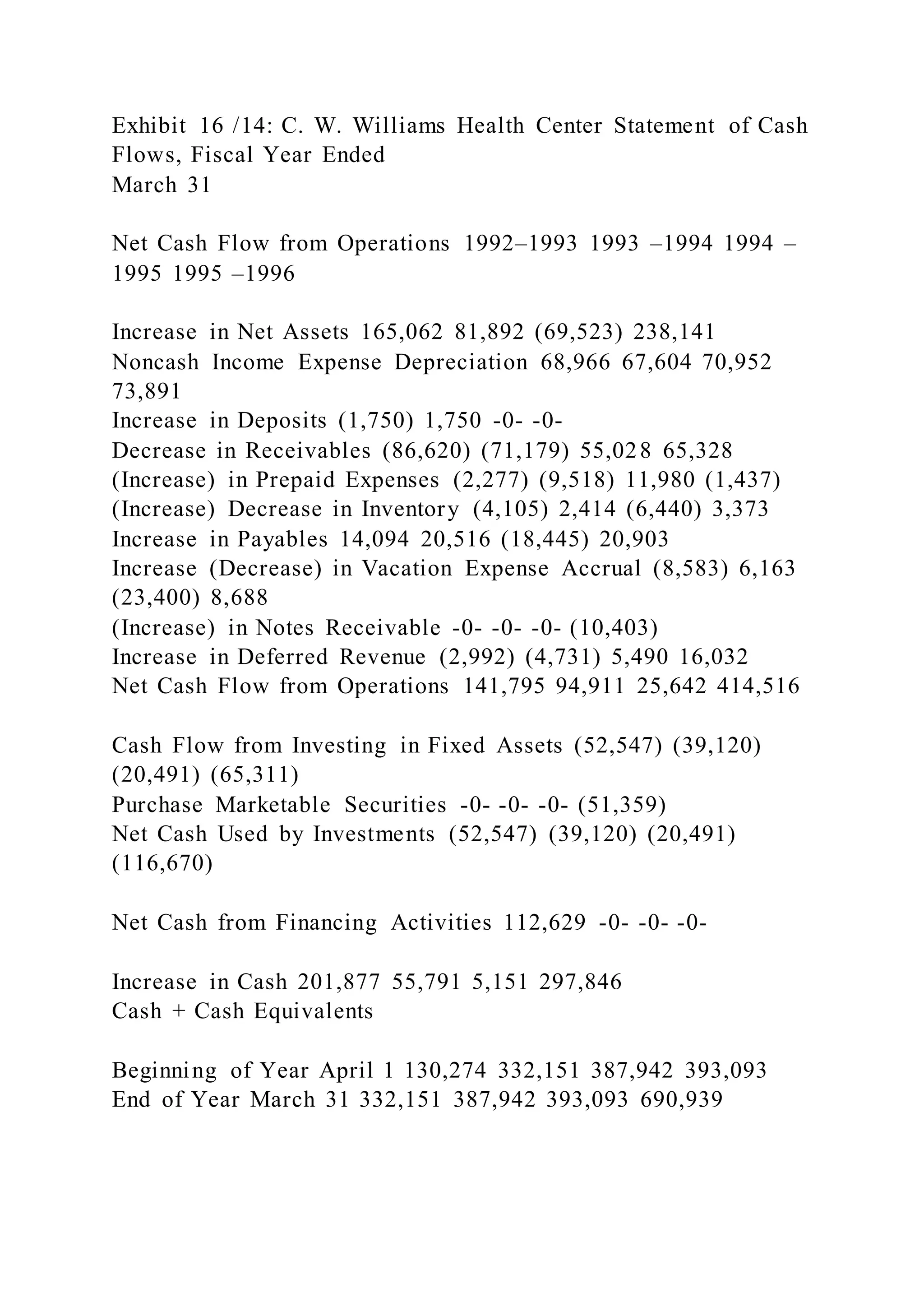

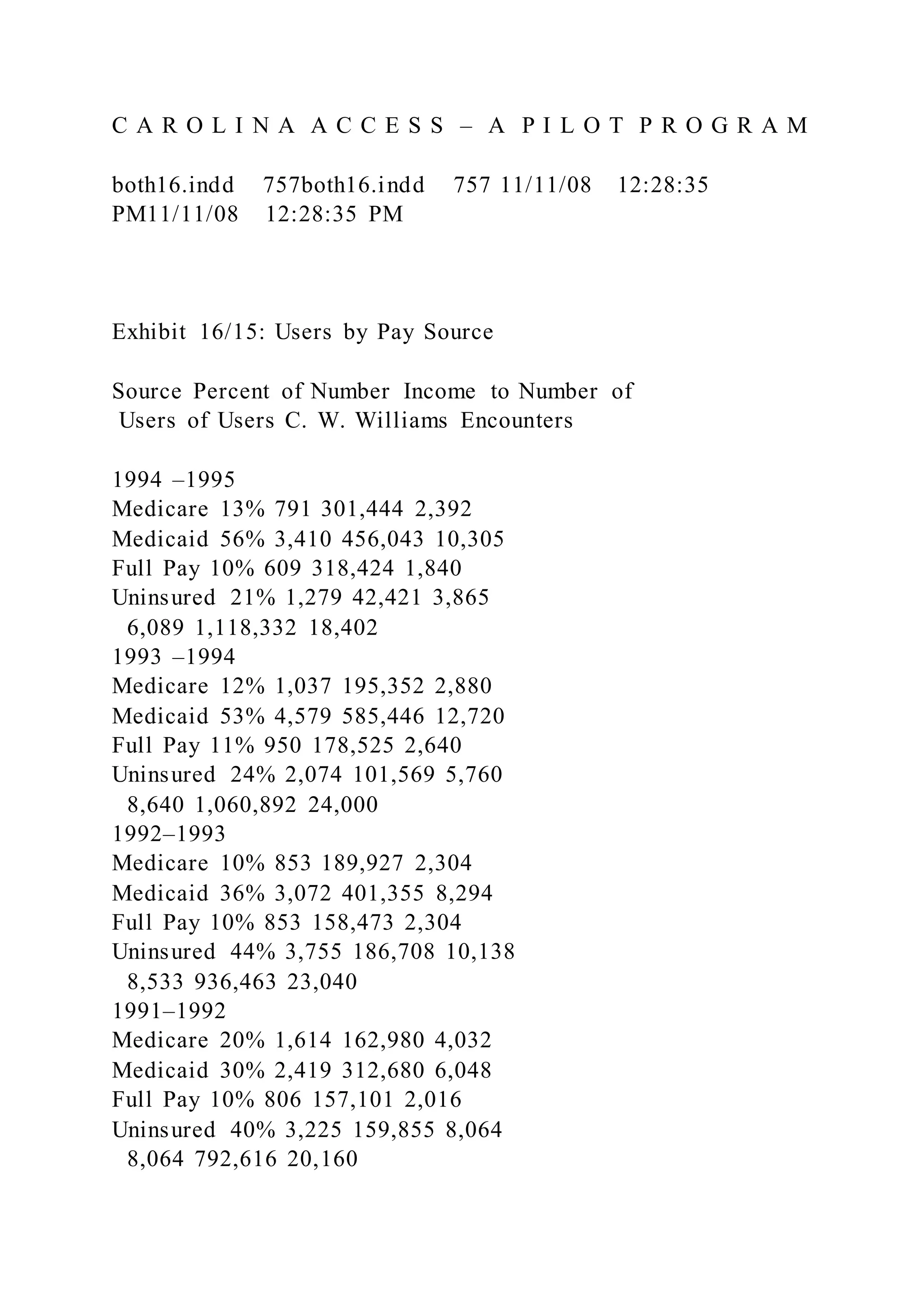

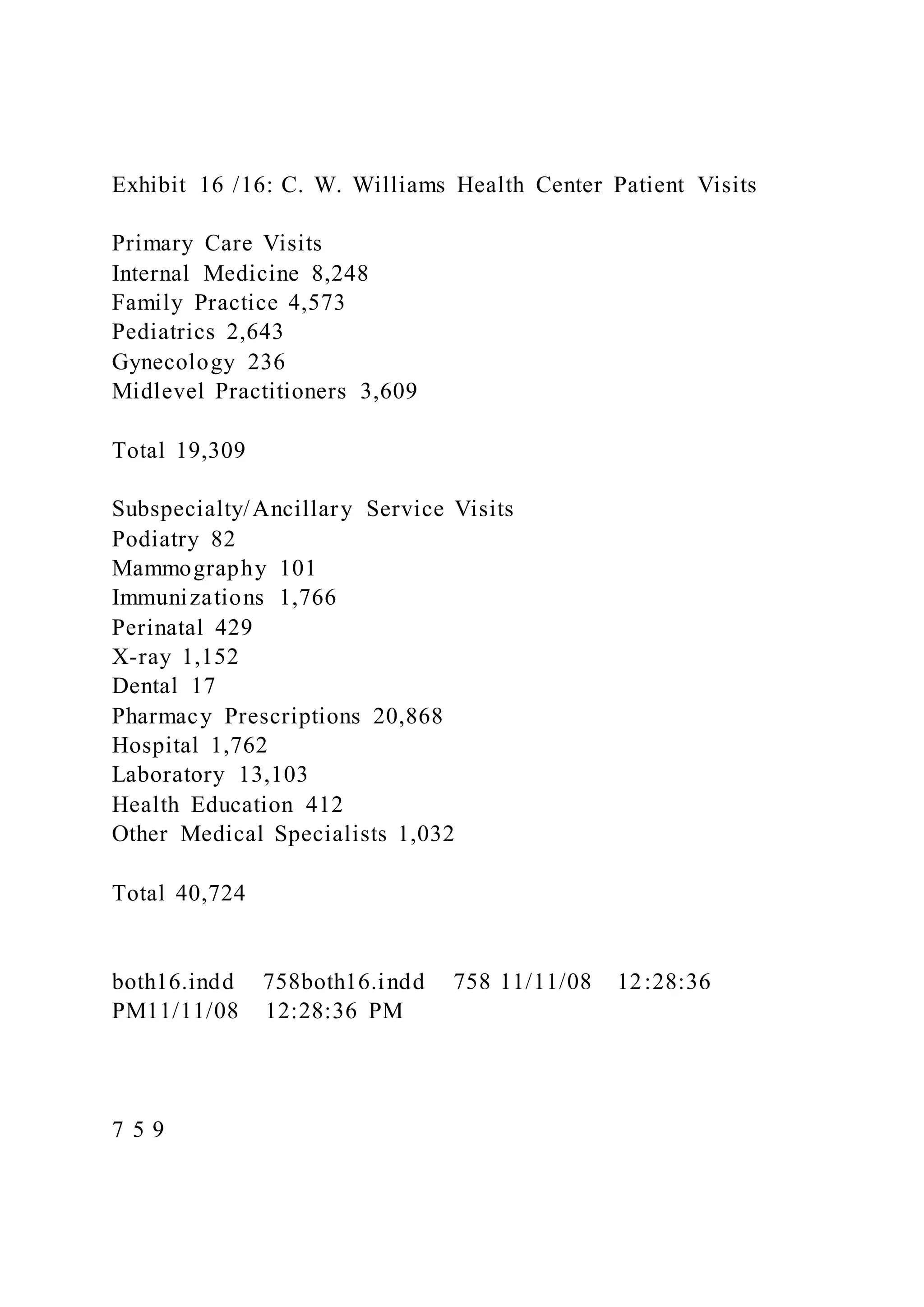

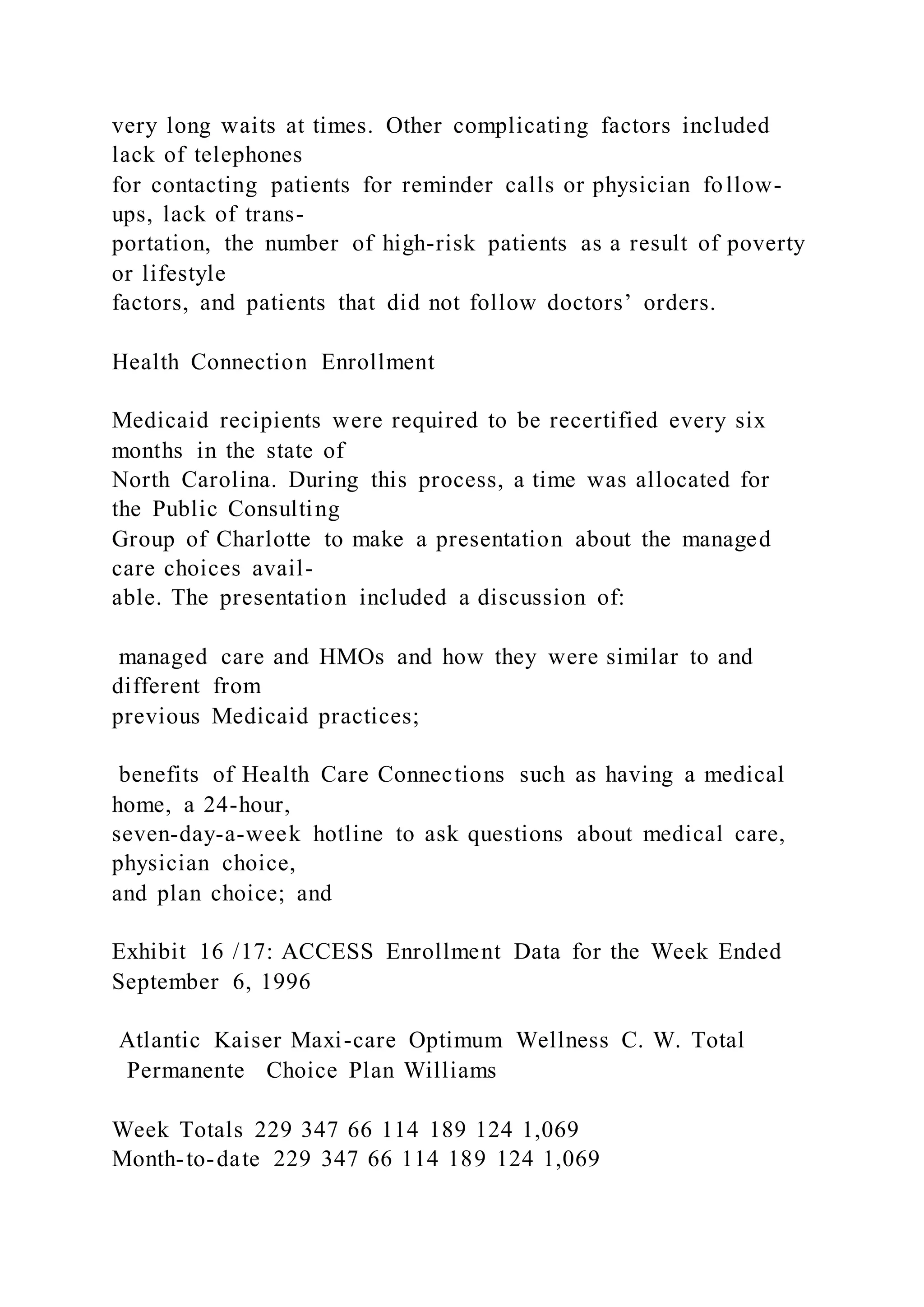

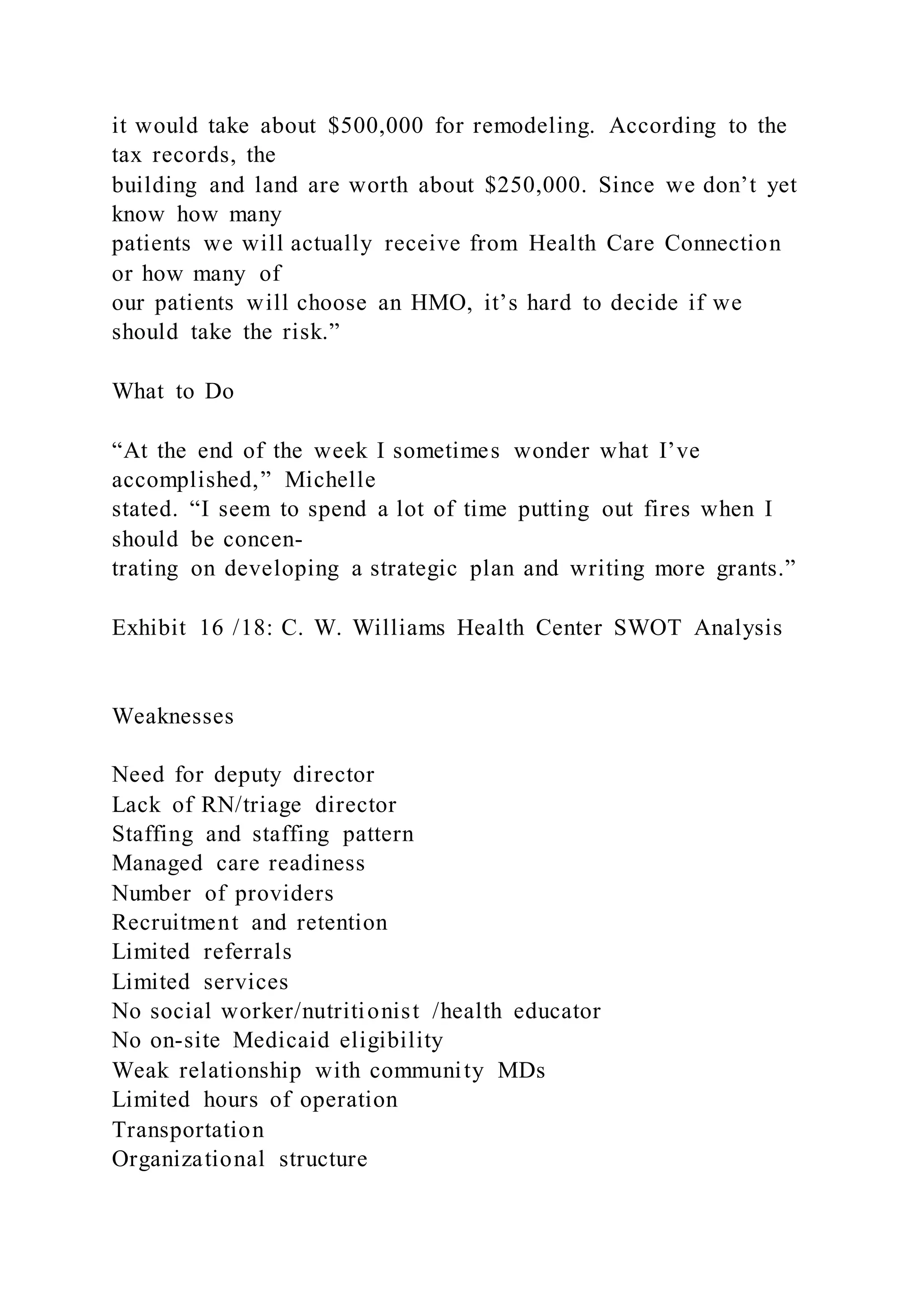

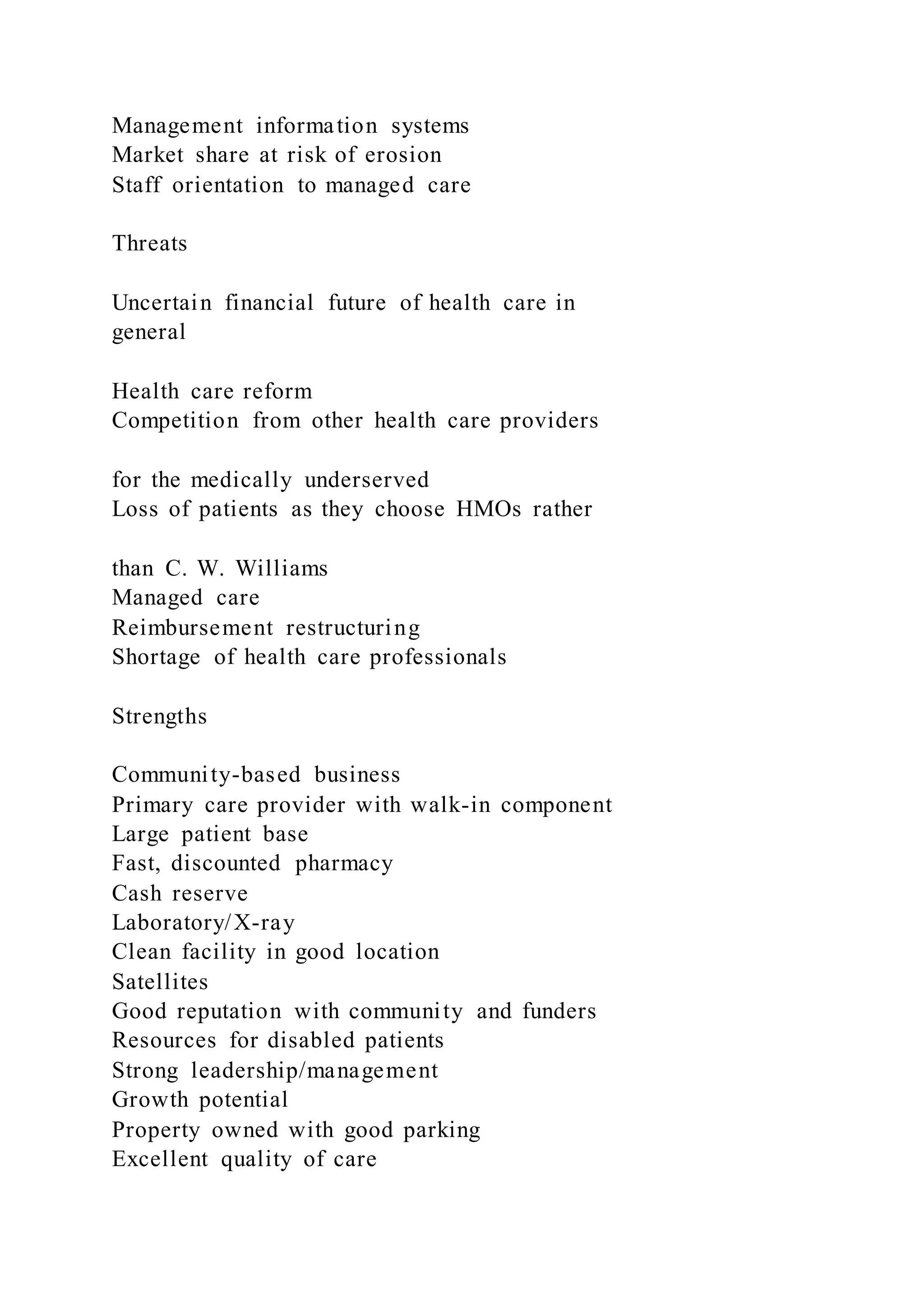

The document outlines an interview assignment template for special education teachers and details the history and operational challenges of the C.W. Williams Health Center, founded to serve the underserved population in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. It highlights the center's mission to provide accessible health care and discusses the impact of managed care on operations, funding, and recruitment. The center's evolution reflects broader trends in community health care and the challenges of integrating services to meet critical community needs.