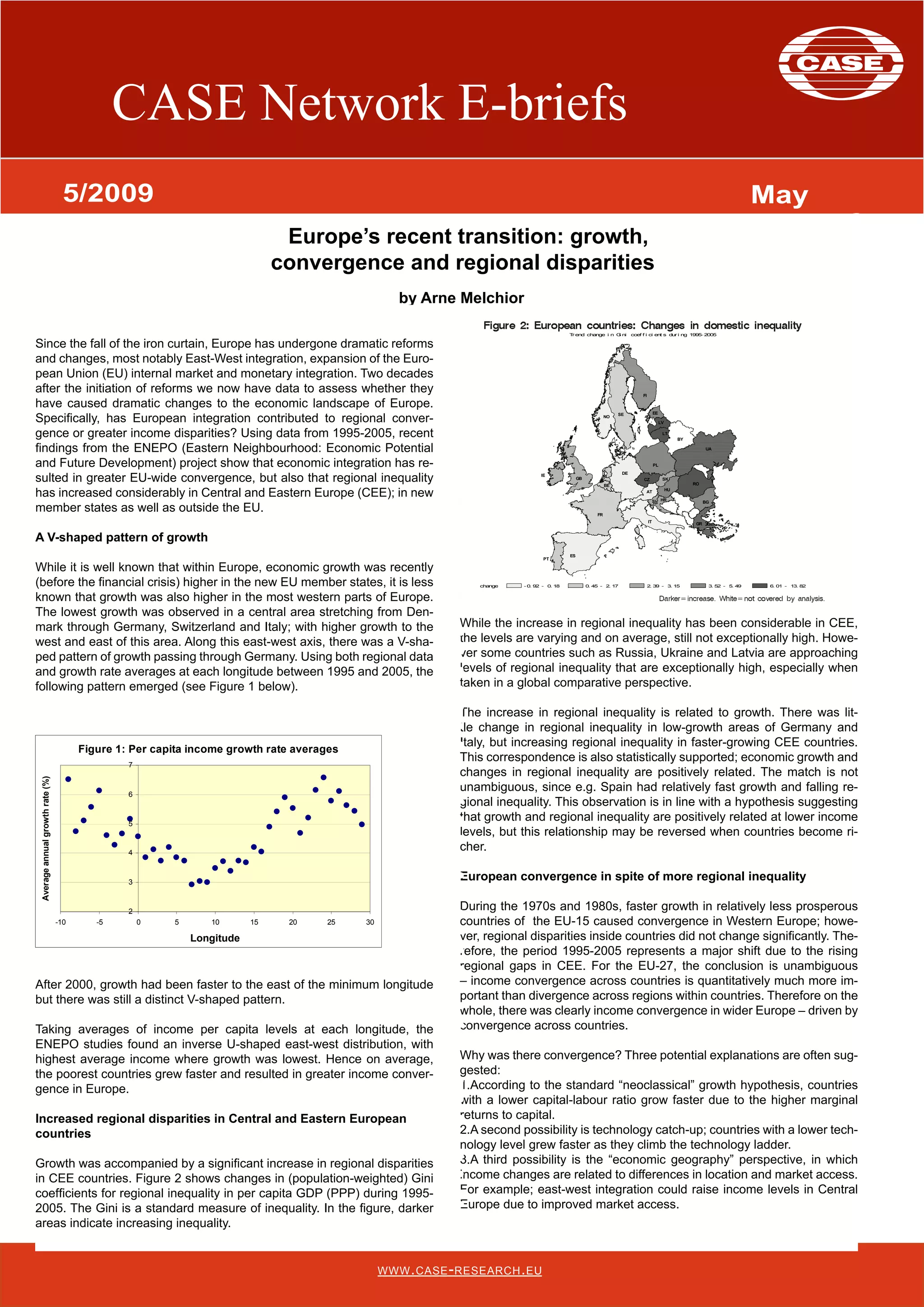

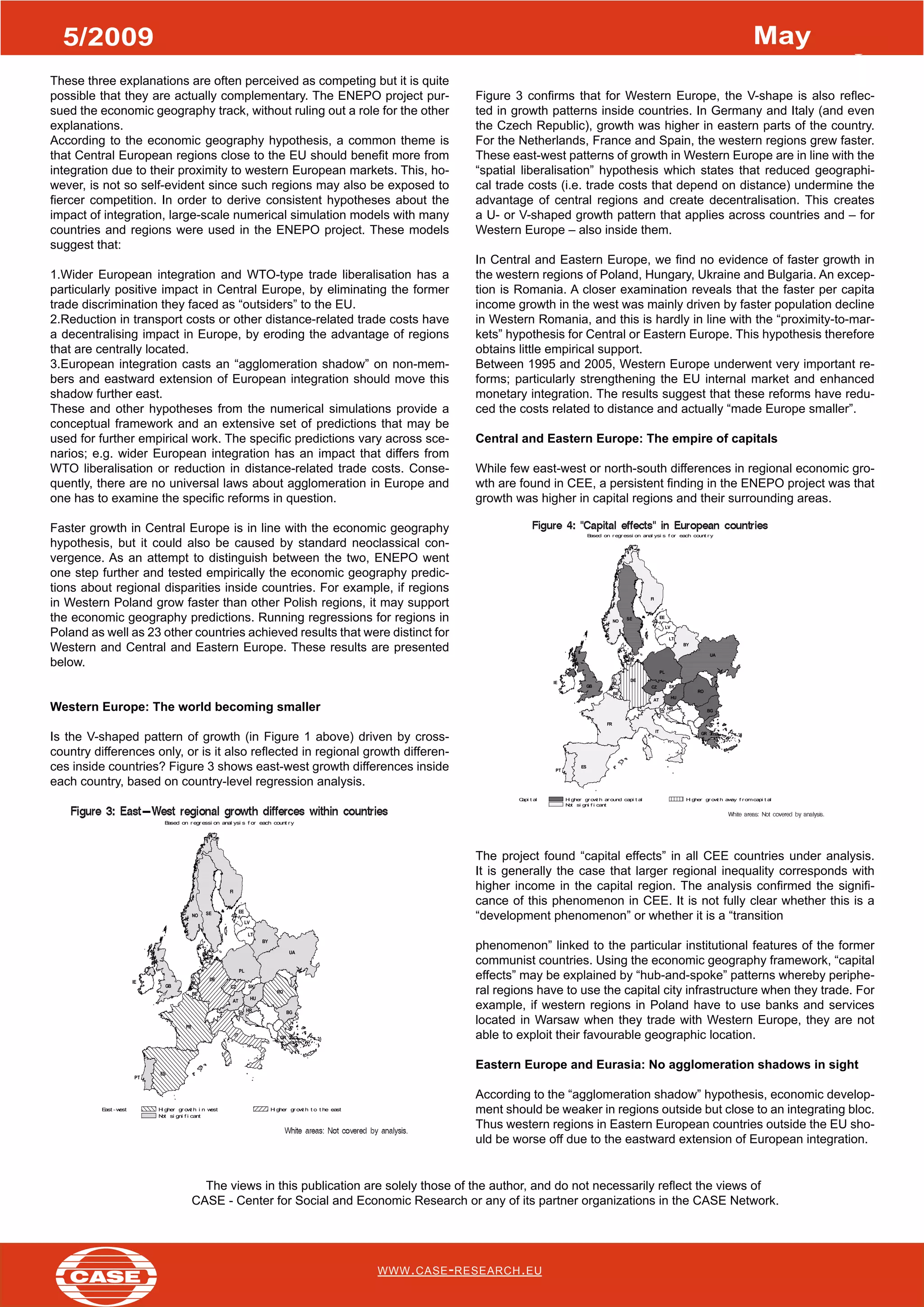

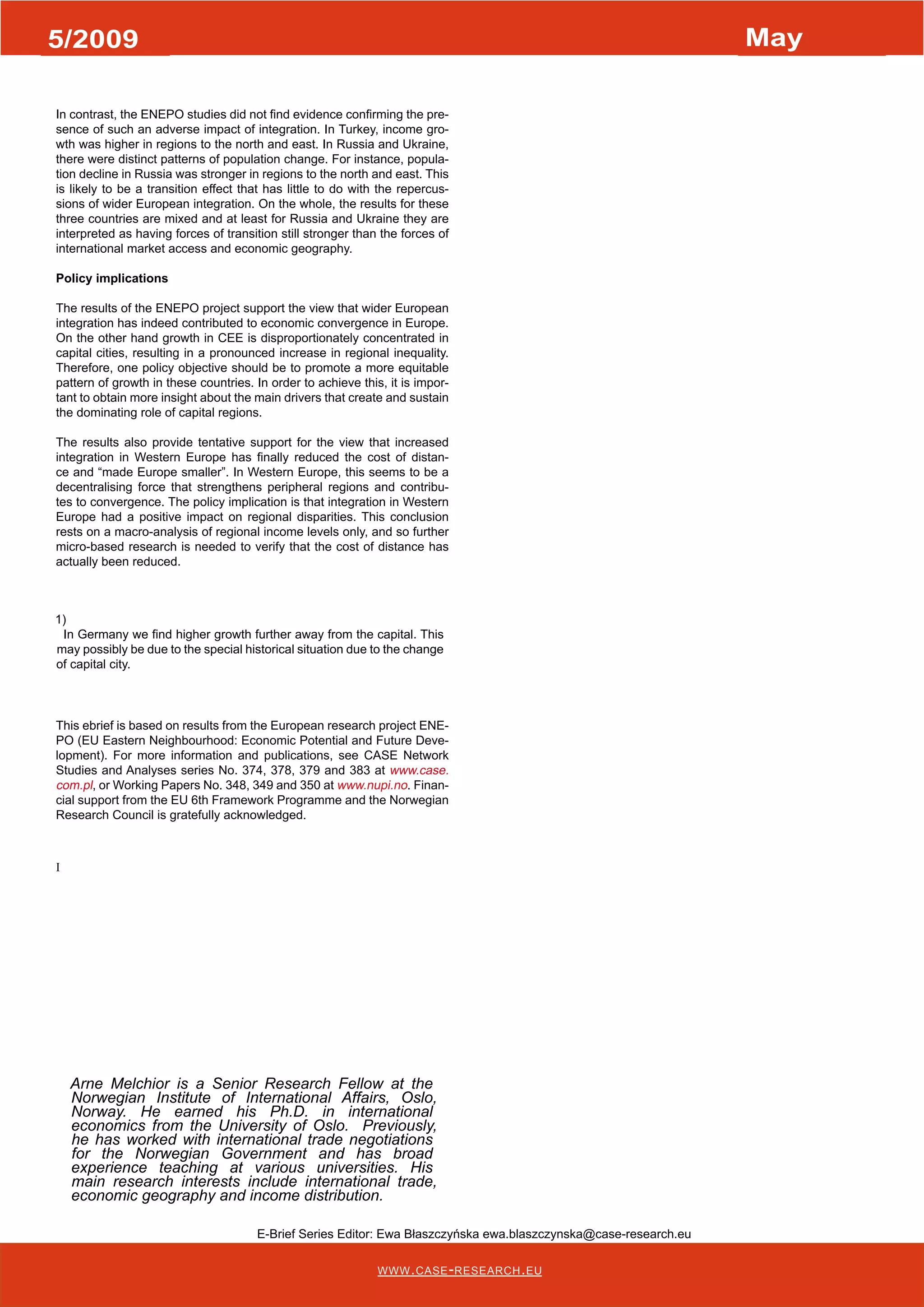

The document analyzes Europe's economic landscape changes following its integration post-Iron Curtain, revealing a V-shaped growth pattern and increased regional disparities, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). While income convergence across countries has been observed, regional inequalities have risen, especially in capital cities, necessitating policy measures to promote more equitable growth. The findings support wider European integration's role in economic convergence but highlight the challenges posed by regional disparities within CEE countries.