This document provides an overview of disturbances in perception, including illusions and hallucinations. It defines illusions as misperceptions of real sensory stimuli, while hallucinations occur in the absence of stimuli. Various types of illusions and hallucinations are described based on etiology, sensory modality, and other factors. Both illusions and hallucinations can affect individuals without psychiatric disorders under unusual conditions like fatigue, sensory deprivation, or grief. The document also discusses other perceptual distortions and how perception is influenced by mood, anxiety, attention, and other psychological factors.

![94

TREATMENT OF MENTAL DISORDERS

HISTORY OF BIOLOGIC TREATMENT OF MENTAL DISEASES

1869 — Chloral hydrate introduced as a treatment for melancholia and mania

1882 — Paraldehyde introduced for a treatment of epilepsy

1903 — Barbiturates introduced as a sedative and anticonvulsant

1917 — Malaria fever therapy of GPI (psychosis of syphilis) [Ju.Wagner von Jauregg]

1927 — Insulin shock for treatment of schizophrenia [M.Sakel]

1934 — Cardiazol (pentylenetetrazol) induced convulsions [L.Meduna]

1936 — Frontal lobotomies [E.Moniz]

1938 — Electroconvulsive therapy [U.Cerletti, L.Bini]

1940 — Phenytoin introduced as anticonvulsant [T.Putnam]

1948 — Disulphiram introduced for treatment of alcohol dependence [E.Jacobsen, J.Hald]

1949 — Lithium introduced for treatment of bipolar psychosis [J.F.Cade]

1952 — Chlorpromazine introduced [J.Delay, P.Deniker]

1953 — Monoanine oxidase inhibitors treatment of depression [G.E.Crain, N.S.Kline]

1956 — Imipramine (the first tricyclic drug) for treatment of depression [R.Kuhn]

1960 — First tranquilizer — chlordiazepoxide introduced [Roche Laboratories, France]

1963 — Valproic acid introduced as anticonvulsant [France]

1963 — Pyracetam introduced [UCB, Belgium]

1965 — First atypical neuroleptic — clozapine introduced

1971-1988— Several serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors introduced

1986 — Atypical tranquilizer — buspirone introduced

CLASSIFICATION OF PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGICAL DRUGS

Antipsychotics (neuroleptics) — treat the symptoms of psychosis (excitement,

delusions, hallucinations etc.), usually by blocking dopamine and

serotonin receptors.

Antidepressants — treat depressed mood, usually by increasing the activity of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/disturbancesinperception-221018182626-9693a7bd/85/DISTURBANCES-IN-PERCEPTION-pdf-94-320.jpg)

![109

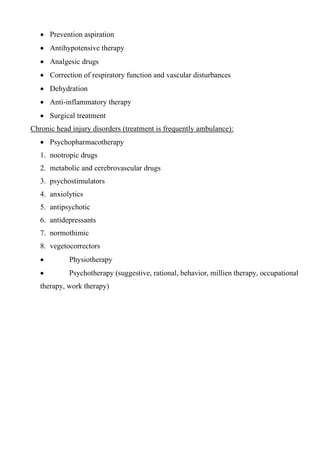

DSM-IV

Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

DSM-IV is a multiaxial system that comprises five axes and evaluates the patient along

each. Axis I and Axis II comprise the entire classification of mental disorders: 17 major

groupings, more than 300 specific disorders, and almost 400 categories. In many

instances, the patient has one or more disorders on both Axes I and II. For example, a

patient may have major depressive disorder noted on Axis I and borderline and

narcissistic personality disorders on Axis II. In general, multiple diagnoses on each axis

are encouraged.

Axis I consists of all mental disorders except those listed under Axis II, and other

conditions that may be a focus of clinical attention.

Axis II consists of personality disorders and mental retardation. The habitual use of a

particular defense mechanism can be indicated on Axis II.

Axis III lists any physical disorder or general medical condition that is present in addition

to the mental disorder. The identified physical condition may be causative (e.g., hepatic

failure causing delirium), interactive (e.g., gastritis secondary to alcohol dependence), an

effect (e.g., dementia and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]-related pneumonia), or

unrelated to the mental disorder. When a medical condition is causally related to a mental

disorder, a mental disorder due to a general condition is listed on Axis I and the general

medical condition is listed on both Axis I and III.

Axis IV is used to code psychosocial and environmental problems that contribute

significantly to the development or the exacerbation of the current disorder (Table 9.1-4).

The evaluation of stressors is based on the clinician's assessment of the stress that an

average person with similar sociocultural values and circumstances would experience

from psychosocial stressors.

Axis IV: Psychosocial and Environmental Problems

✓ Problems with primary support group

✓ Problems related to the social environment

✓ Educational problems

✓ Occupational problems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/disturbancesinperception-221018182626-9693a7bd/85/DISTURBANCES-IN-PERCEPTION-pdf-109-320.jpg)

![115

Schisophrenia

(www.feldsher.ru)

(dementia praecox)

Nosological definition

(by Emil Kraepelin and Eugen Bleuler)

1. Aetiology: Endogenous

2. Structure deterioration: no, functional disorder

3. Course: chronic progressive. Outcome: stable

defect of personality

[with autism, formal disorders of thought and

impoverishment of will and emotions, up to apathy,

abulia and schizophrenic dementia (if malignant

cases)].

4. Symptoms and syndromes:

Productive symptoms Negative symptoms

Disorders of sensation

and perception

cenesthopathy,

pseudohallucinations,

depersonalisation,

derealisation

subjective feeling of self-

changing (depersonalisation)

Thought disorders alienation of thoughts,

mentism, thought blocking,

persecutory

delusions (delusion of

control), overvalued ideas,

obsessions

autism, ambivalence,

reasoning, schizophasia,

obscurity of expression,

paralogia, symbolism,

philosophical intoxication,

pontifical woolliness (up to

incoherence) etc.

Affective disorders anxiety, perplexity (acute

delusion), mania or

depression may be, but not

specific

ambivalence, decreased

affect (monotonous,

flattering and incongruity of

affect), apathy](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/disturbancesinperception-221018182626-9693a7bd/85/DISTURBANCES-IN-PERCEPTION-pdf-115-320.jpg)

![117

f) Thought broadcasting

g) Delusional perceptions

h) All other experiences involving volition, made affects,

and made impulses

ICD-10

According to ICD-10 the diagnosis of schizophrenia cannot be established without 1-

month duration criterion. Conditions clinically equal to schizophrenia but of duration less

than 1 month (whether treated or not) should be diagnosed in the first instance as acute

schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder [F23.2] and reclassified as schizophrenia if

symptoms persist for longer periods.

It is specially marked that 1-moth duration criterion applies only to the specific

symptoms (like listed above) and not to any prodromal nonpsychotic phase.

Also mentioned that diagnosis of schizophrenia should not be made in the presence of

extensive depressive or manic symptoms unless it is clear that schizophrenic symptoms

antedated the affective disturbance.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/disturbancesinperception-221018182626-9693a7bd/85/DISTURBANCES-IN-PERCEPTION-pdf-117-320.jpg)

![120

oneiroid states, pseudohallutinations etc.)

Pseudoneurotic schizophrenia

(e.g. cenesthopathic schizophrenia)

F21 — mild disorder which has no connection

with stress and appears with subpsychotic

symptoms (obsession, phobia, depersonalization,

overvalued ideas) and sluggish progression of

schizophrenic negative symptoms.

F20.8 — endogenous form of hypochondria

with strange inner sensations (cenesthopathia).

Types of course

F20.*0 Continuous progression

F20.*1 Progression with acute attacks [German - Schub]

F20.*3 Periodic (recurrent)

F21 Special type with slow (sluggish) progression — In ICD-10 Schizotypal disorder

(eccentric, bizarre behavior — German – Verschroben).

progression with acute attacks

slow (sluggish) progression

periodic (recurrent)

with slow progression

P +

N -

—

P +

N -

—

P +

N -

—

continuous progression

P +

N -

—](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/disturbancesinperception-221018182626-9693a7bd/85/DISTURBANCES-IN-PERCEPTION-pdf-120-320.jpg)

![121

ORGANIC MENTAL DISORDERS F00 - F09

SPECIFIC SYMPTOMS (Walter-Buel H. triad):

1. Difficulties in retention (up to amnesia – F04)

2. Difficulties in understanding (up to dementia – F00-F03)

3. Difficulties in keeping feelings in (e.g. disphoria or emotional incontinence)

ADDITIONAL SYMPTOMS:

4. Changes in personality and general behaviour [F07]

5. Neurological signs and symptoms

6. Asthenia (emotional hyperaesthetic syndrome)

7. Somatic symptoms (headache etc.)

8. Weather sensitivity.

METHODS OF DIAGNOSTIC:

✓ EEG](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/disturbancesinperception-221018182626-9693a7bd/85/DISTURBANCES-IN-PERCEPTION-pdf-121-320.jpg)

![5

Hallucinations in delirium

(www.feldsher.ru)

✓ CT (Computer Tomography) or

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

✓ Ophthalmologist examination

✓ Neurologist examination

✓ Rheoencepalography

✓ Doppler ultrasound

✓ Cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) tests

✓ Neuropsychological tests

PSYCHO-ORGANIC SYNDROME

A heterogeneous group of states usually

observed in individual stages of the course

of various organic diseases. In the first

stages of development, increasing manifestations of mental weakness and increased

fatigability are usually discovered. Later these are joined by disorders of attention,

memory and intellectual activity, psychopathic like disturbances, and various emotional

disorders. Delirium [F05], true hallucinations and delusional disturbances [F06] may be

observed. Delusional disturbances are fleeting and fragmentary, with no tendency

towards systematization, and they vary in content. Affective disorders fluctuate from an

uplifted mood with euphoria to depression and increased irritability, peevishness,

sometimes with an overlay of dysphoria and maliciousness.

DEGENERATIVE

CEREBRAL

DISEASES

Alzheimer’s disease [F00, G30] – degenerative disease with

insidious onset at age 55—65 or later (occur in women 3-5

times more often than in men) with prominence of features of

parietal and temporal lobe damage (loss of memory, apraxia,

acalculia, dysgraphia, dysartria). It develops slowly but

steadily. Formal complaints coexist with poor insight (total](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/disturbancesinperception-221018182626-9693a7bd/85/DISTURBANCES-IN-PERCEPTION-pdf-122-320.jpg)

![Рисунок 2 – Деперсонализация при нервной анорексии

dementia).

Pick’s disease [F02, G31] – a progressive dementia with onset

at age 50-60 with features of selective atrophy of frontal and

temporal lobe (apathy, euphoria, severe character changes,

verbal and motor stereotypy). The course is rather malignant;

no sense of illness exists (total dementia).

CEREBRAL

ARTERIOSCLEROSIS

System disease with slow progression and evident waving

course. Cerebral symptoms coexist with features of ischaemia

of heart or extremities. The first symptoms are asthenia and

hypomnesia. Dementia appears later, insight is rather good

(partial dementia – F01)

TUMOURS Neurological symptoms are common in onset (paralysis,

disorders of co-ordination of movement, disorders of vision,

epileptic seizures etc.). If the frontal lobes are impaired, the

changes of character, apathy and poor insight are typical. The

symptoms of cranial hypertension are common (headache

with retching increasing by the morning, clouding of

consciousness).

TRAUMA Acute or chronic regressive course. Stages are: loss of

consciousness (up to coma), acute period (sometimes with

acute psychosis, for example delirium), convalescence

(through the stage of asthenia), consequences (cerbrasthenia,

Korsakov’s syndrome, dementia, epileptic seizures,

personality disorder).

INFECTIONS GPI (general paralysis of insane – F02.8, A52.1) – syphilitic

psychosis which appears in some patients in 10-15 years after

infection. The symptoms of encephalitis are the loss of

insight, euphoria, dementia, severe personality changes,

delusions of grandeur. Neurological signs: Argyll-Robertson

symptom, asymmetry of tendon reflexes. Wassermann test is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/disturbancesinperception-221018182626-9693a7bd/85/DISTURBANCES-IN-PERCEPTION-pdf-123-320.jpg)

![positive in 95% of patients. Treatment: antibiotics,

iodotherapy, bismuth drugs.

AIDS dementia [F02.4, B22.0] – up to total is common in

terminal phase. Treatment is symptomatical.

EPILEPSY G40

Nosological definition:

1. Aetiology: Endogenous

2. Structure deterioration:

organic

3. Course:chronic

progressive.

Outcome: Epileptic dementia (if malignant cases).

4. Symptoms and syndromes:

Productive symptoms: rather different but ever paroximal.

Negative symptoms: stable defect of personality with egocentrism (selfishness),

circumstantiality (stiffness), emotional rigidity and

explosivity.

Epilepsy

(rus-img.com)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/disturbancesinperception-221018182626-9693a7bd/85/DISTURBANCES-IN-PERCEPTION-pdf-124-320.jpg)

![Реактивная депрессия F32 – Depressive episode

Посттравматическое стрессовое

расстройство (ПТСР)

F43.1 – Post-traumatic stress disorder

Реактивный параноид

F23.31 – Other acute predominantly

delusional psychotic disorders (including

paranoid reaction)

NEUROSES (неврозы)

Неврастения

F48.0 – Neurasthenia

Невроз навязчивых состояний

F40 – Phobic anxiety disorders,

F41 – Other anxiety disorders

(including panic disorder),

F42 – Obsessive-compulsive disorder,

F45.2 – Hypochondriacal disorder

(including nosophobia)

Истерический невроз

F44 – Dissociative [conversion] disorders,

F45 – Somatoform disorders

Ипохондрический невроз

F45.2 – Hypochondriacal disorder

(nondelusional)

Депрессивный невроз

F34.1 – Dysthymia,

F43.2 – Adjustment disorders,

F43.1 – Post-traumatic stress disorder

Acute Stress Induced Psychoses

Nosological definition:

1. Aetiology: psychogenous, the result of acute irresistible stressors concerning the

primary personal needs (safety, health, honour, freedom and so on)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/disturbancesinperception-221018182626-9693a7bd/85/DISTURBANCES-IN-PERCEPTION-pdf-129-320.jpg)

![the kind of neurosis depends upon the type of personality.

‘intellectual’ type with predominance of the second set of conditioned stimuli (language,

logic, operating with symbols) over the first is common for patients with

obsessive-phobic neurosis

‘artistic’ type with predominance of the first set of conditioned stimuli (emotions,

sensations and intuition) over the second is common for patients with hysteric

neurosis

According to S.Freud

the symptoms of neuroses represent unconscious psychological defense against the

irresistible internal conflicts (often sexual problems). Unconscious motives are the cause

of the poor insight and resistance against the treatment.

CLINICAL FORMS

Neurasthenia appears with the symptoms of asthenia (fatigability in combination with

irritability) that are linked to meaningful psychological stressors.

Symptoms:

Psychological: tiredness, poor memory, sleep disorders, lack of restraint,

psychological sensibility (appeared with tears or verbal violence).

Somatic: functional pain (headache, stomachache, and backache), arterial hypo- or

hypertension, palpitation, sweating, linked to psychological troubles or

physical difficulties.

Hysteria (dissociative [conversion] disorders, somatoform disorders, somatization

disorder) is characterized by physical or psychological symptoms for which no physical

cause can be identified but which are linked to meaningful psychological stressors. The

symptoms may help patients unconsciously deal with internal conflicts. It is more

common in women and patients with demonstrative (histrionic) features of personality.

It is strongly recommended to make special investigation to exclude any other cause of

the somatic symptoms because about 30% of patients with preliminary diagnose of

hysteria are later diagnosed with organic disorders (cancer, multiple sclerosis,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/disturbancesinperception-221018182626-9693a7bd/85/DISTURBANCES-IN-PERCEPTION-pdf-132-320.jpg)