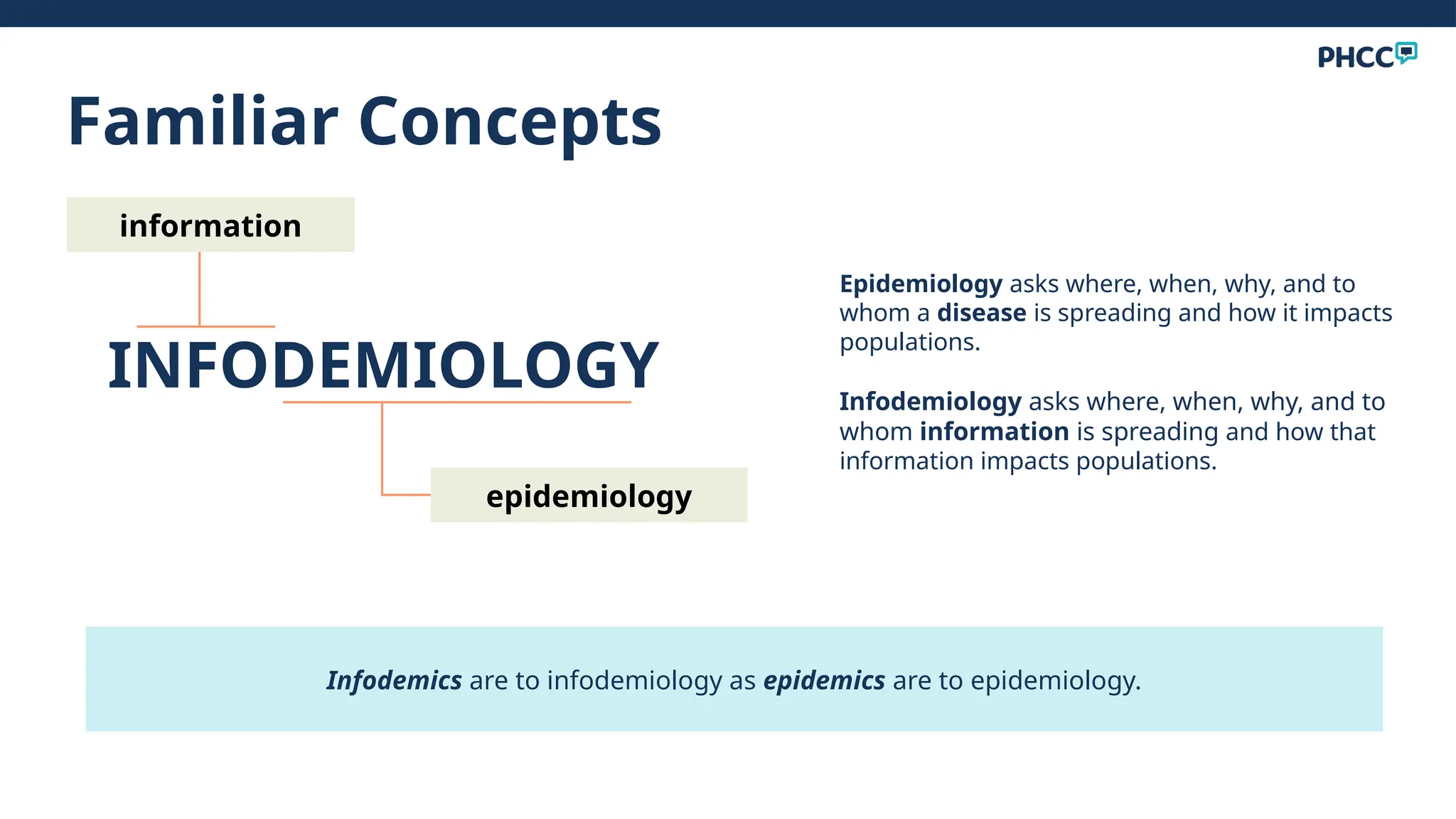

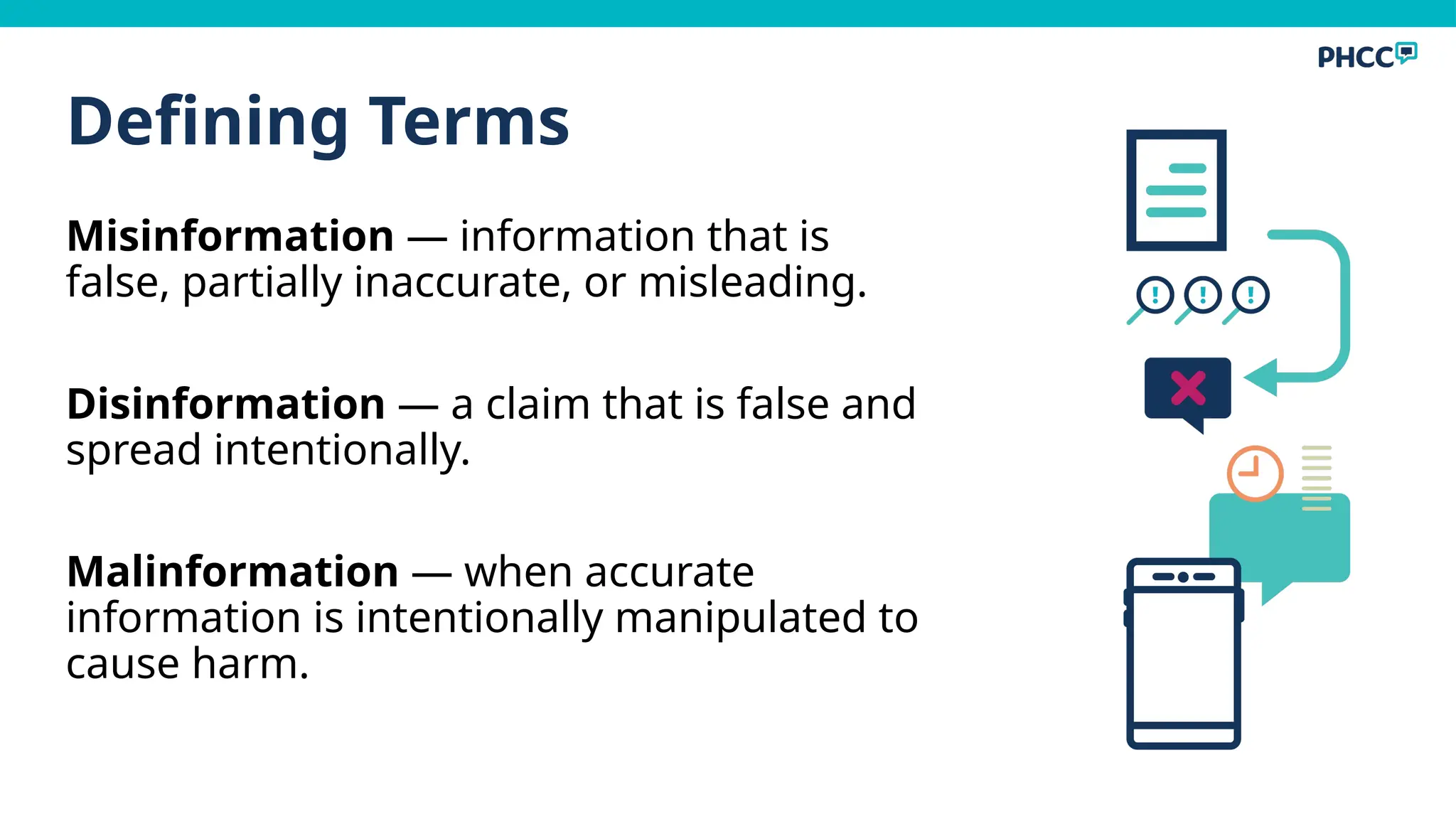

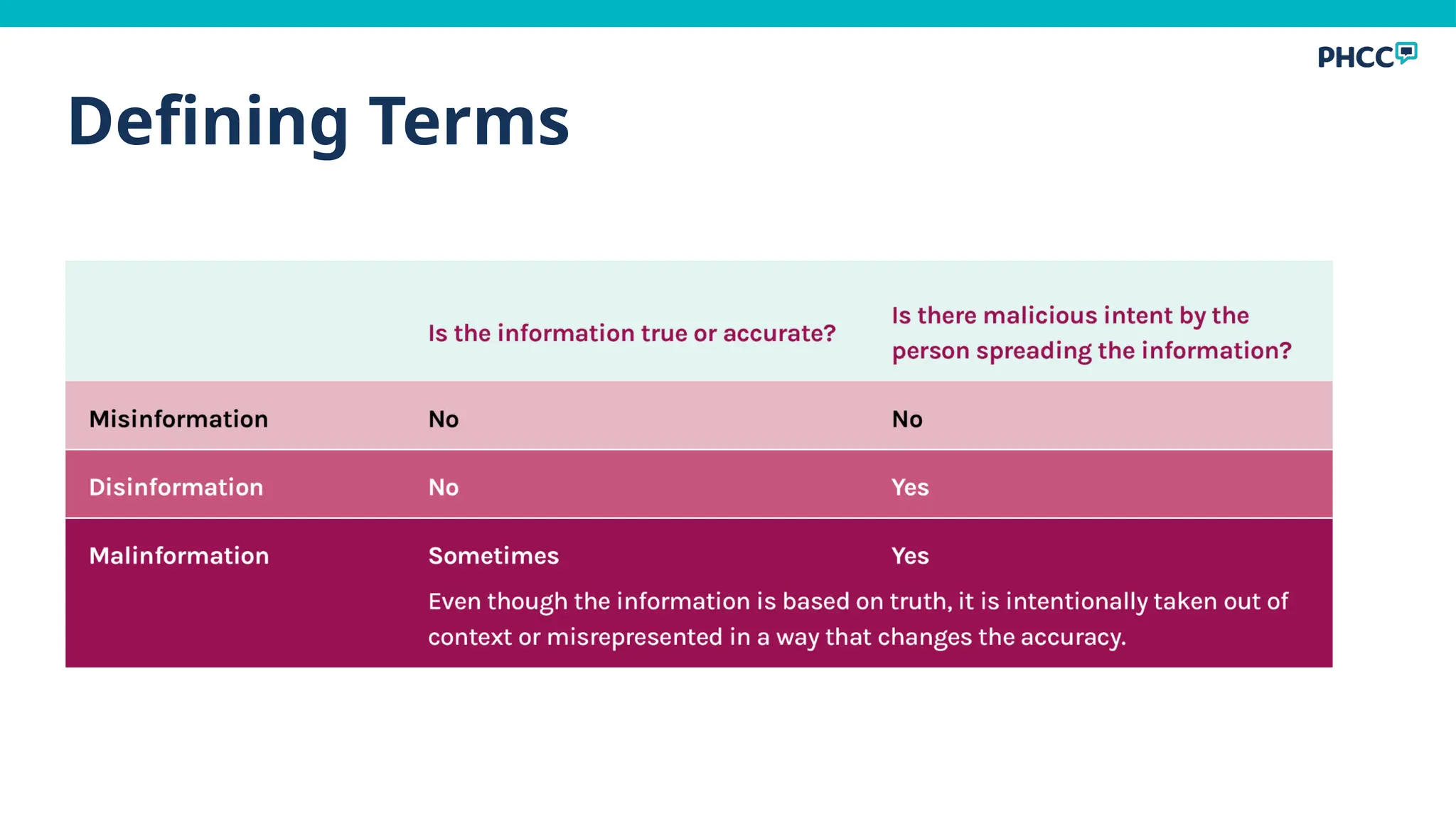

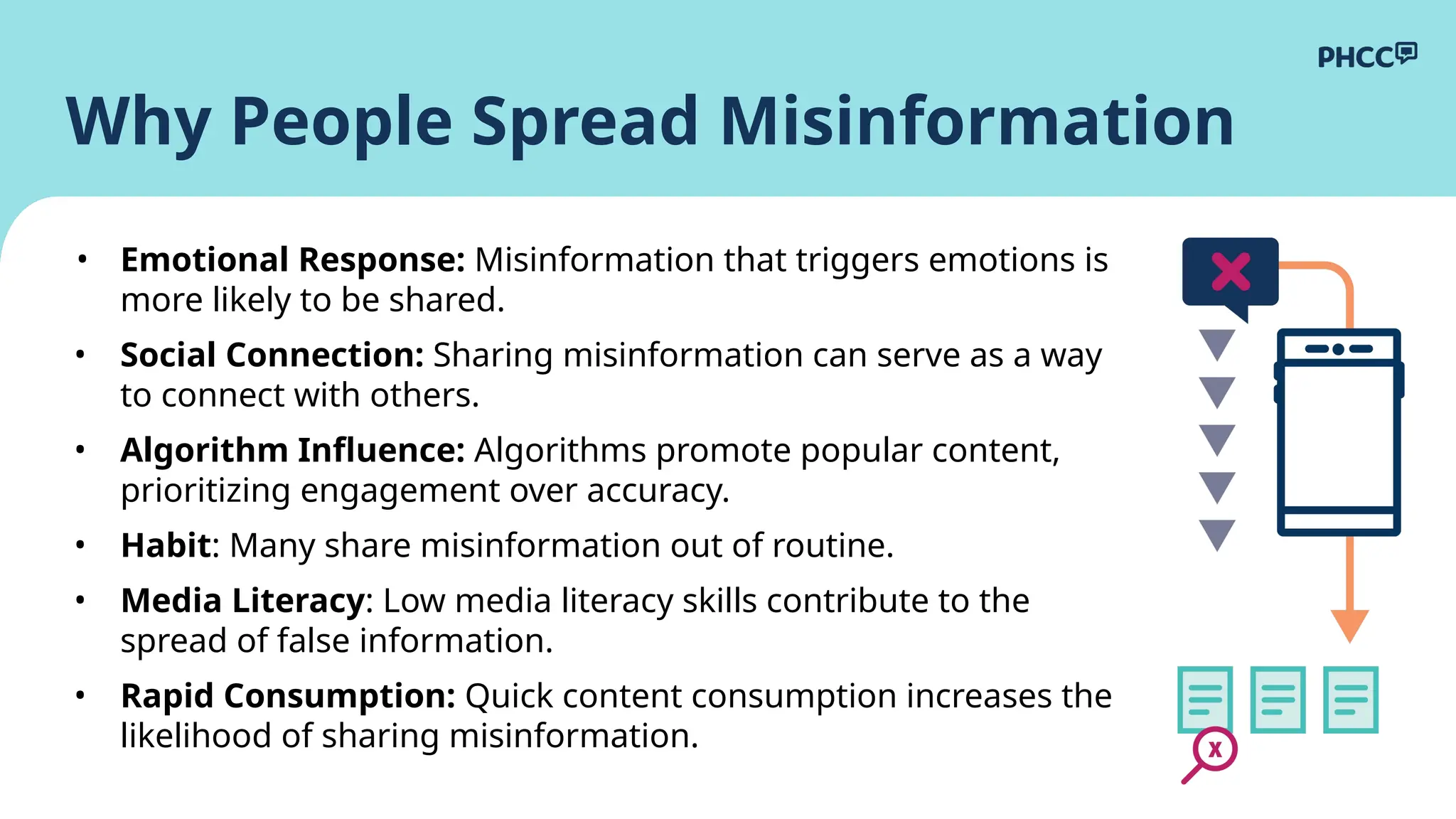

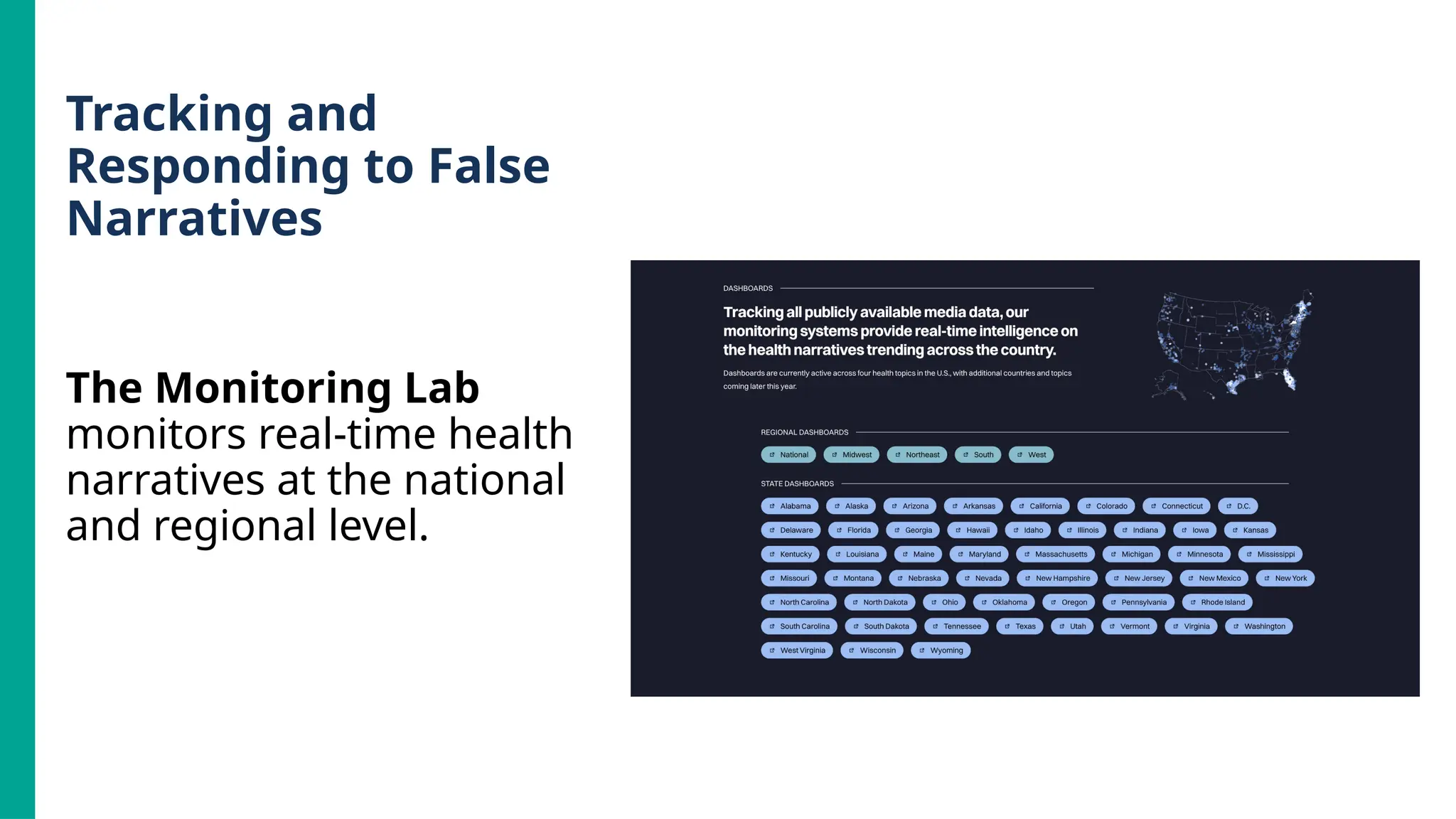

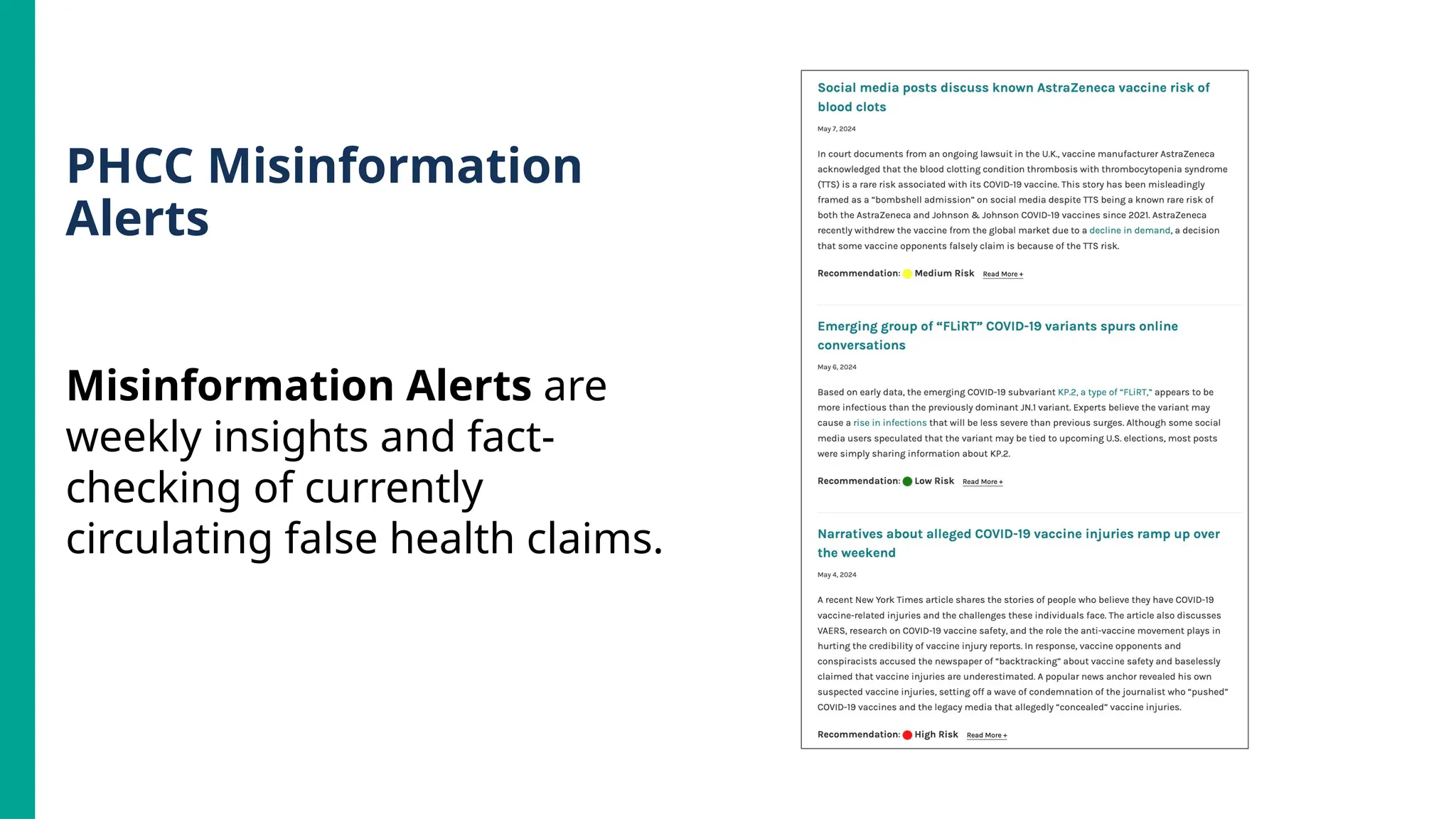

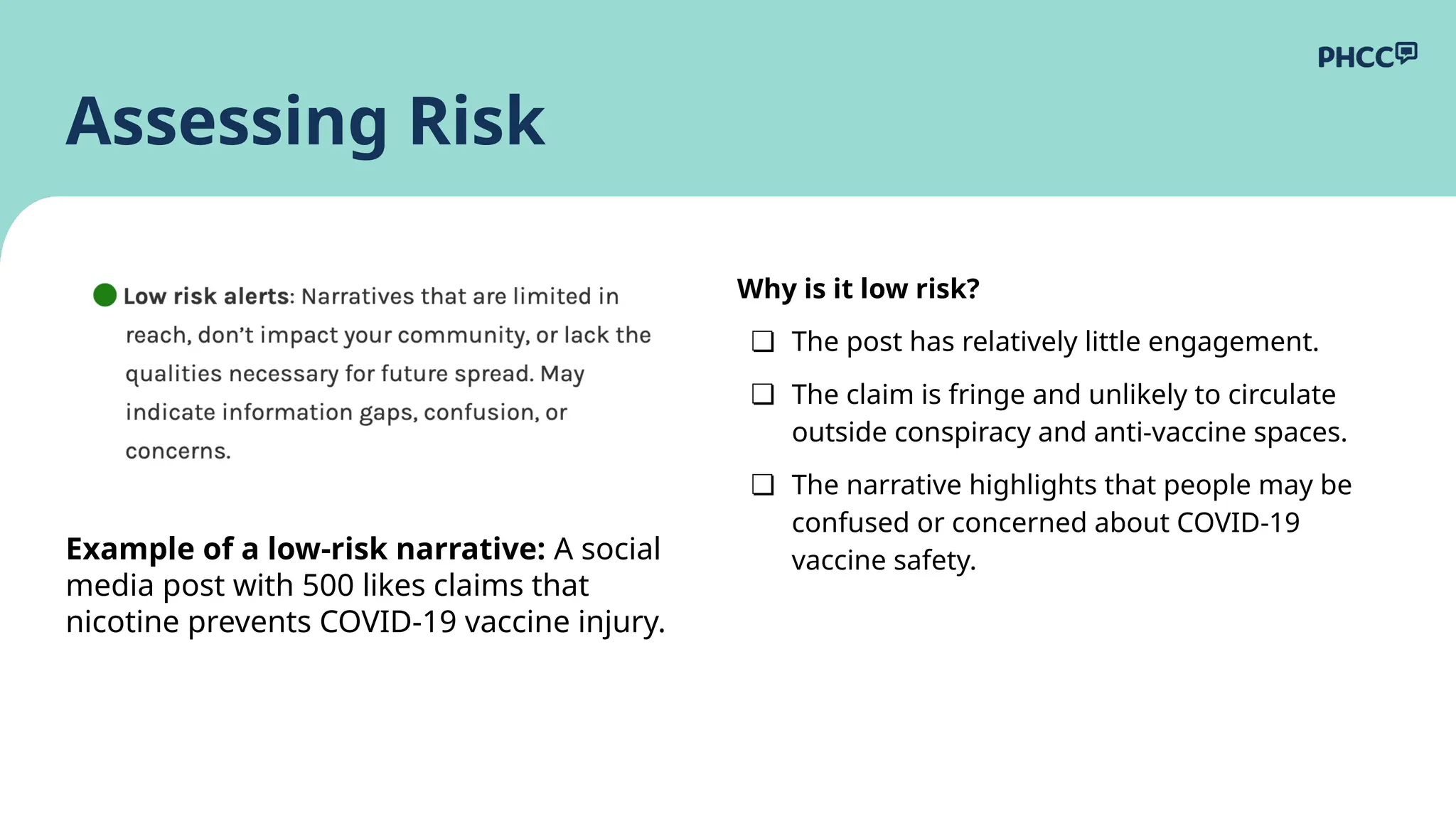

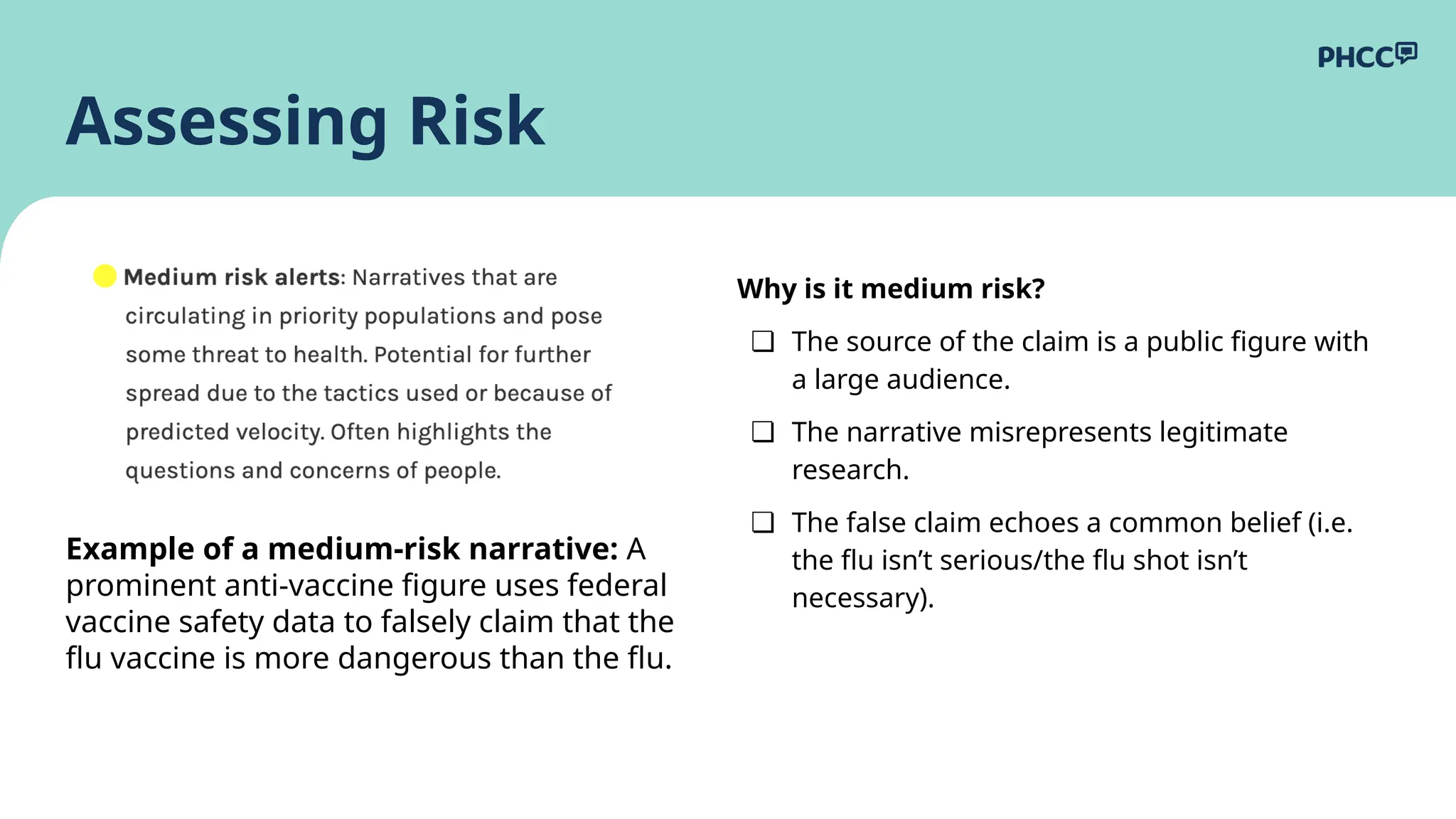

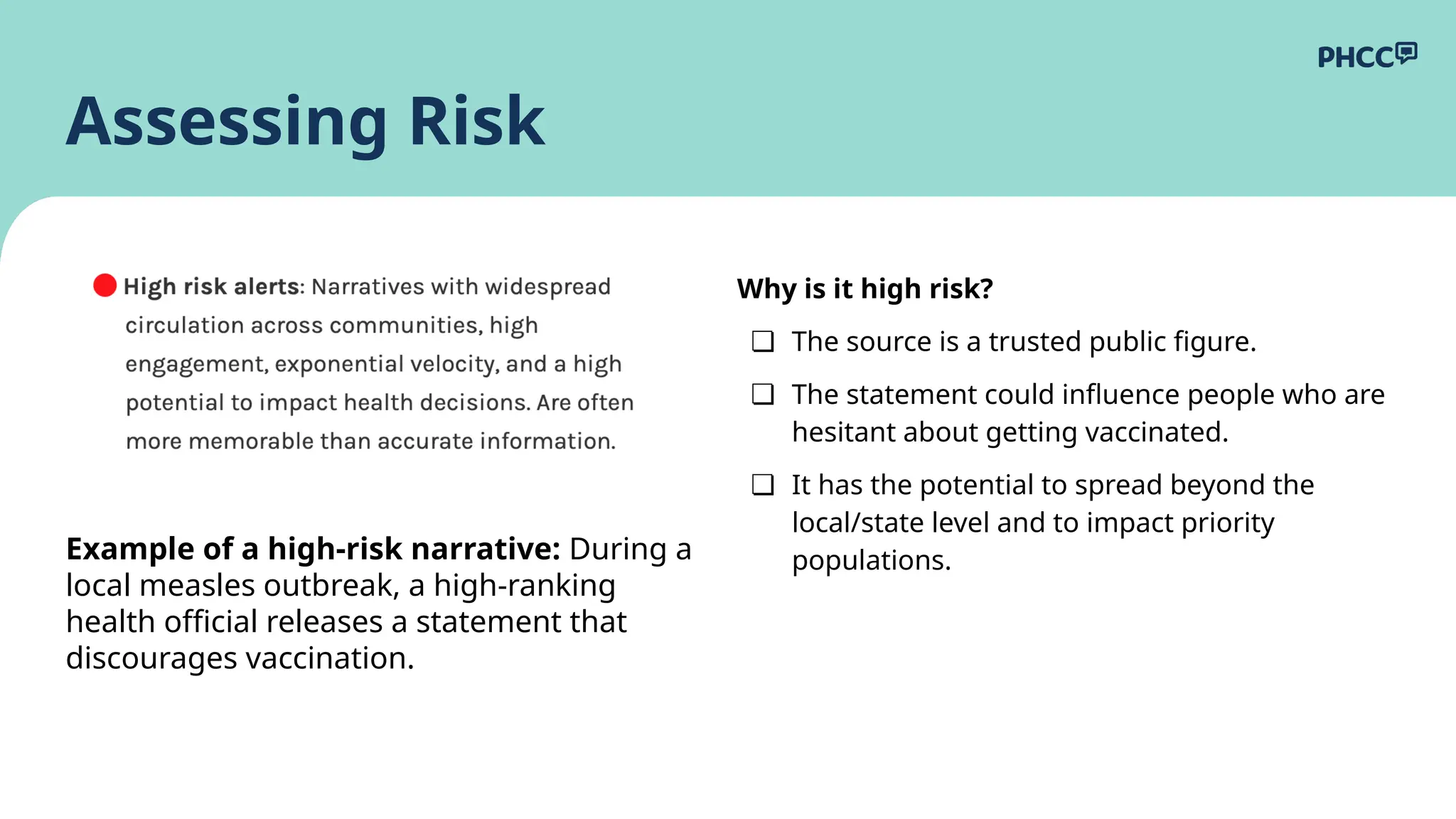

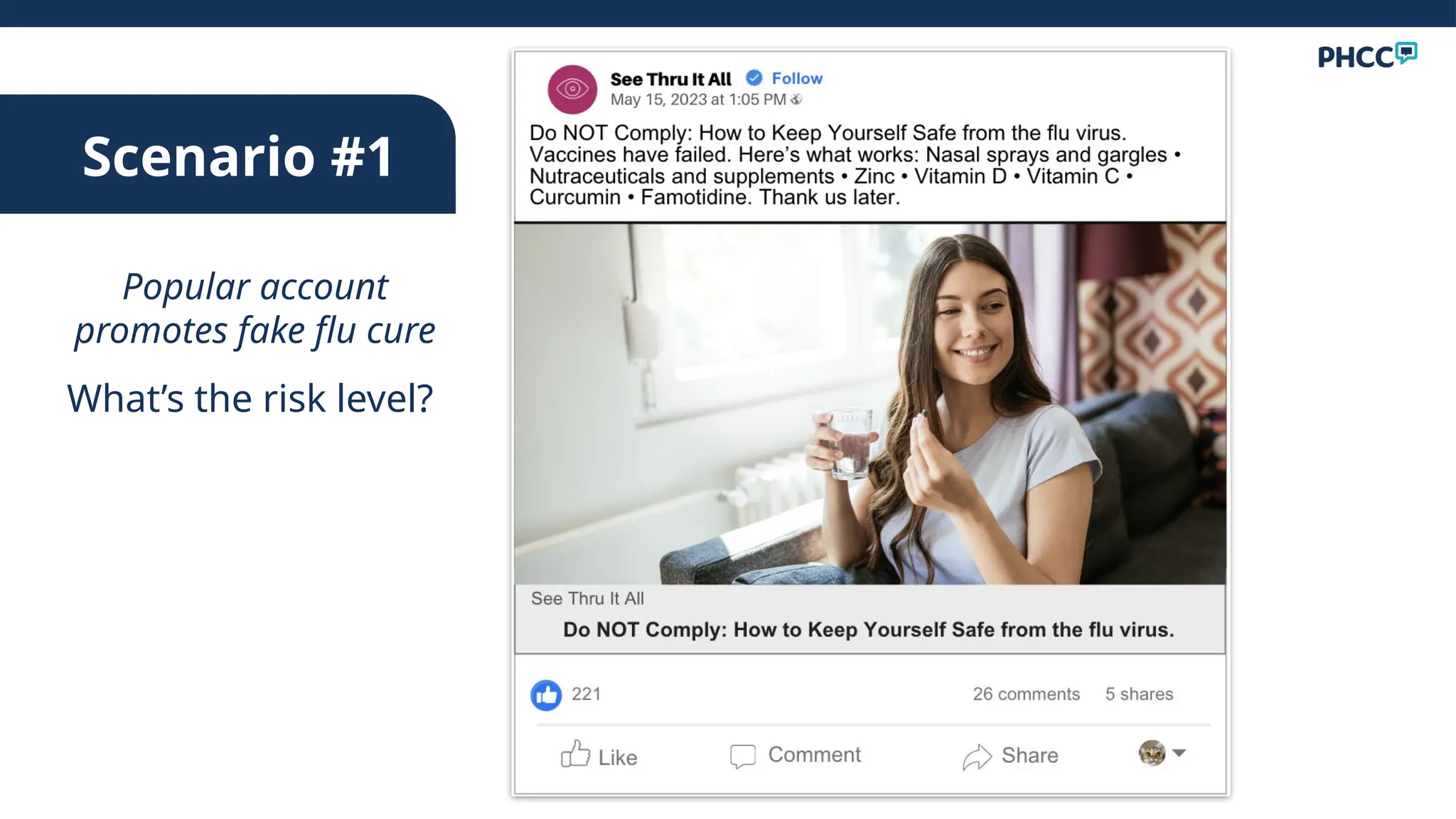

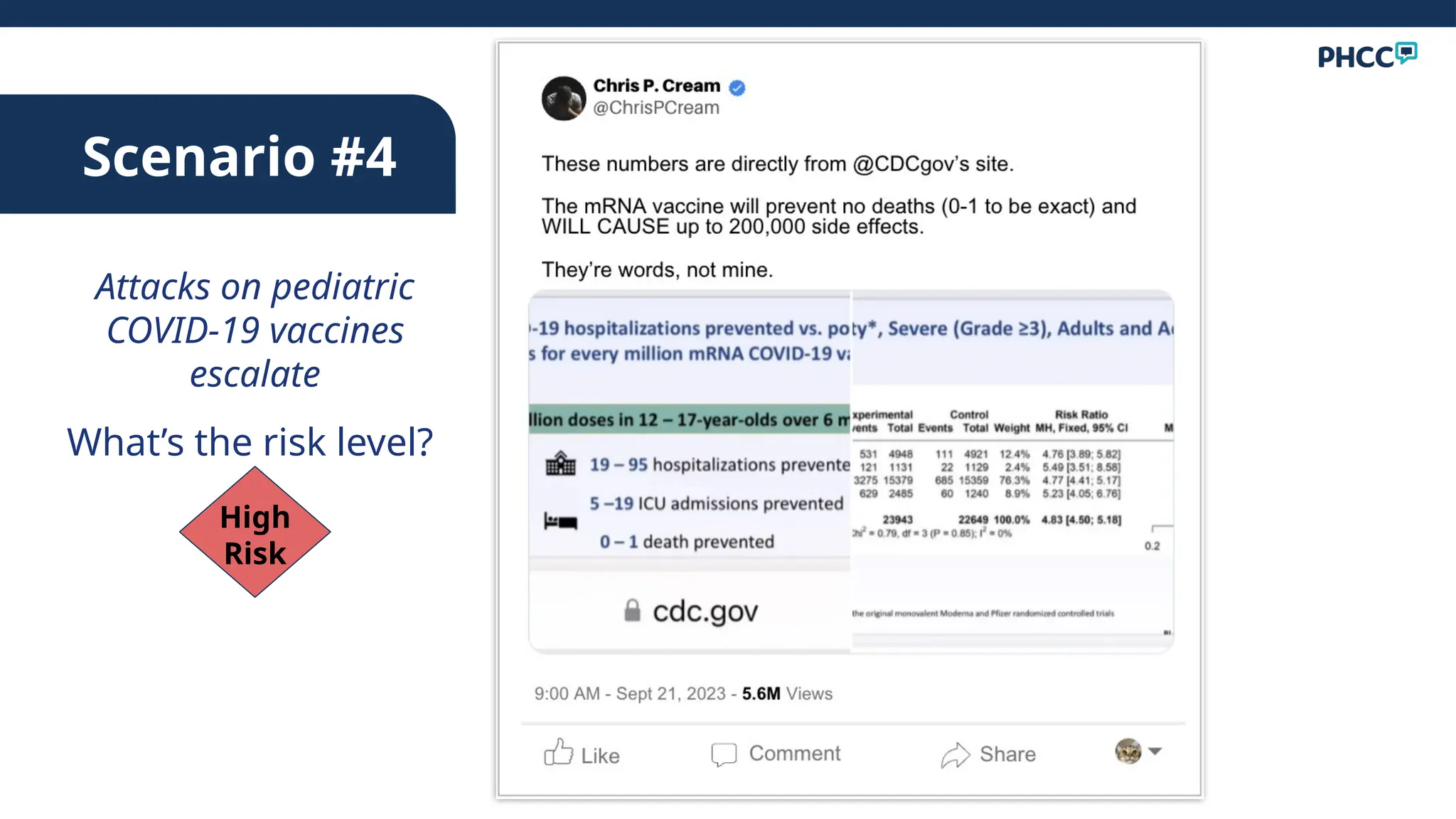

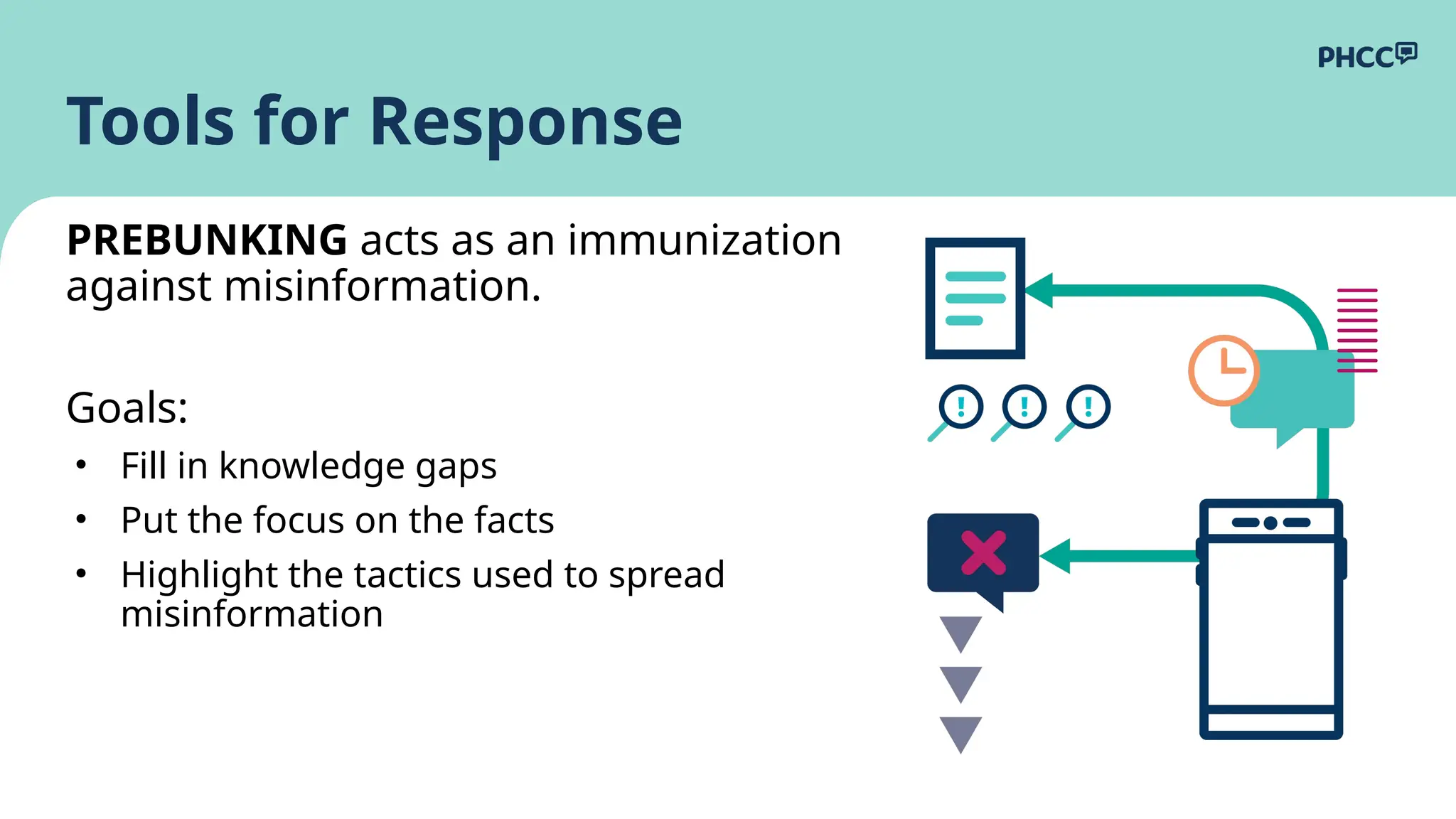

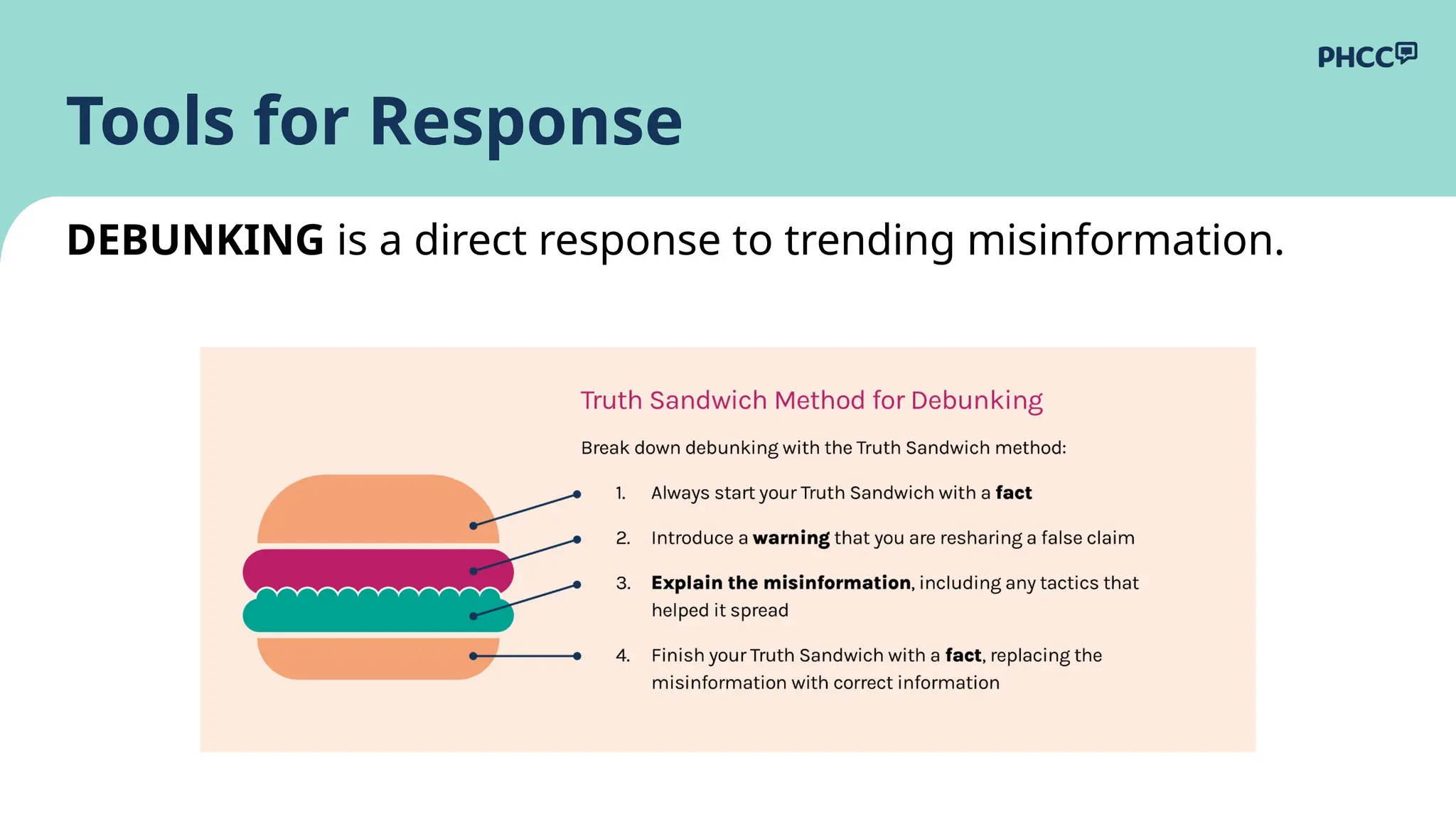

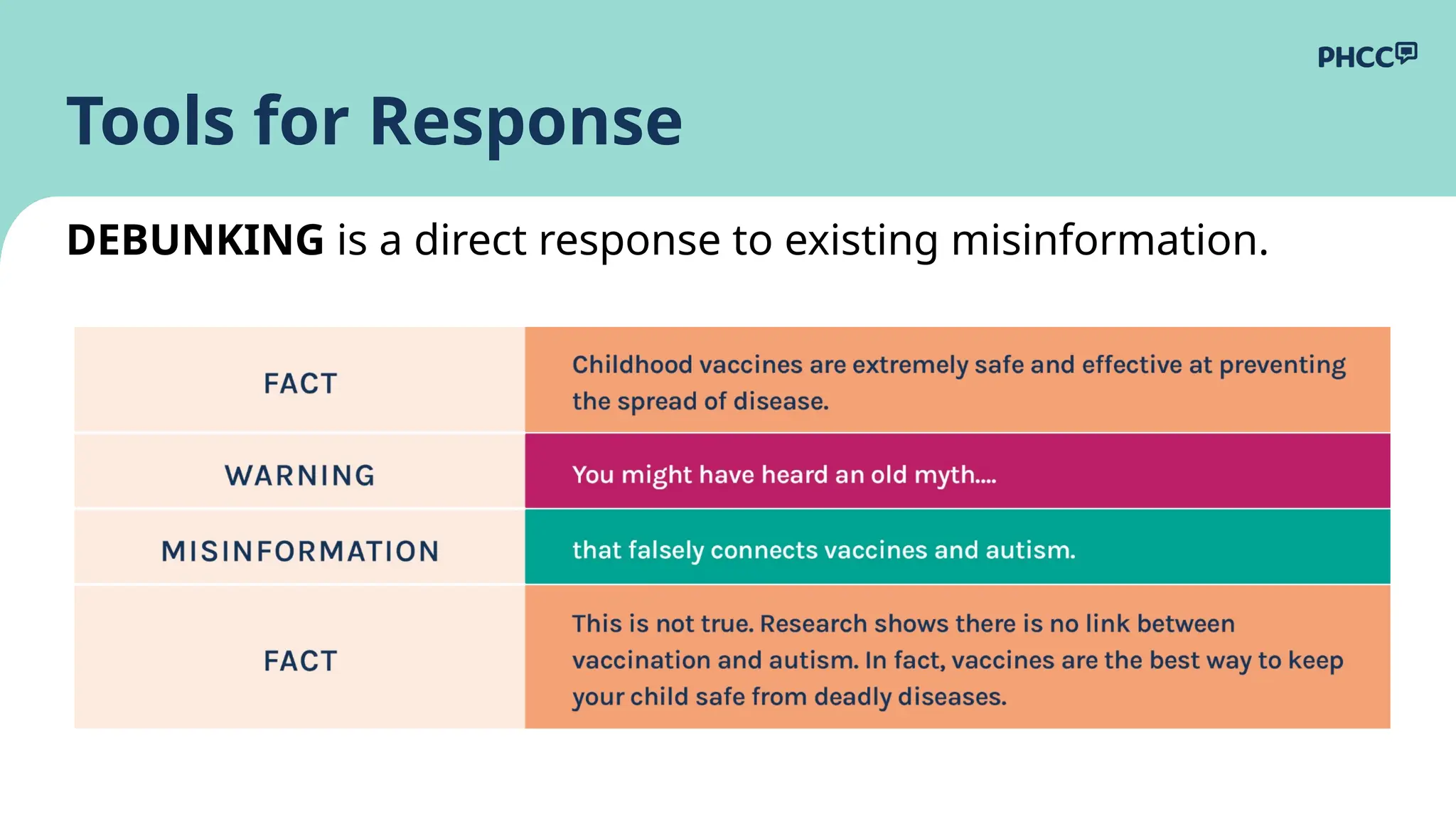

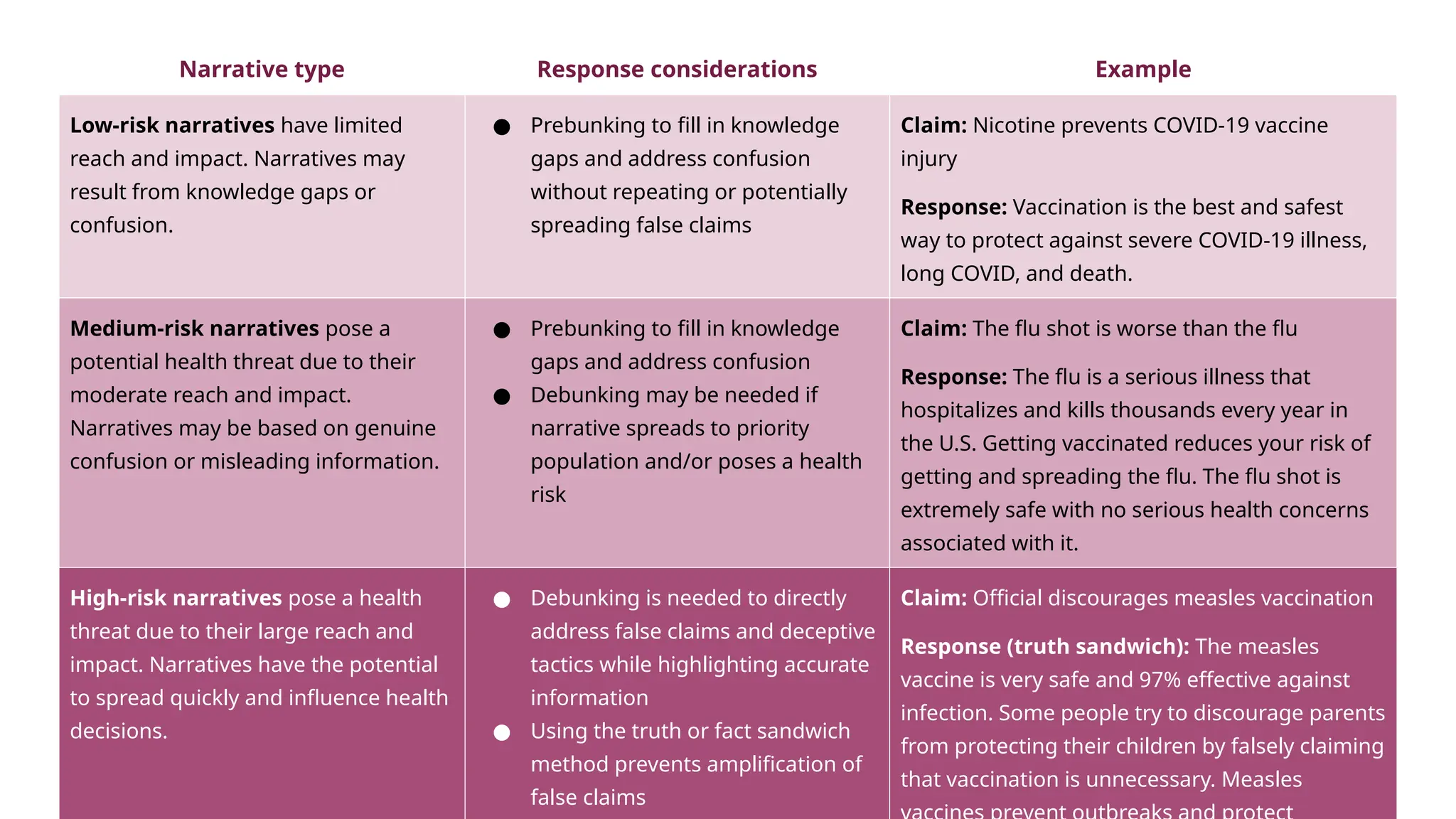

The document outlines a public health event focused on developing a response plan to combat misinformation, particularly in relation to COVID-19 and other health issues. It discusses the prevalence of misinformation, its impact on public trust, and the importance of strategies like infodemiology, prebunking, and debunking to effectively communicate accurate information. Additionally, it emphasizes understanding audience behavior and tailoring messaging to counter misinformation effectively.