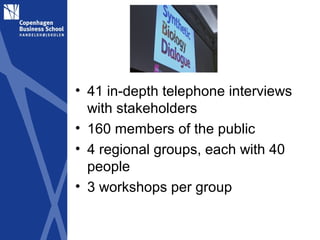

This document discusses public engagement with science and the politics involved. It examines different approaches to engagement like consensus conferences and debates. However, it notes that engagement activities often face criticism for having limited issues, marginal involvement of the public, and resistance from institutions. There is a debate between representing the public and bringing expertise. While engagement aims to be democratic, it can also be a means of legitimation. The document argues we should recognize disagreement and critique as part of engagement rather than assuming consensus will be reached.