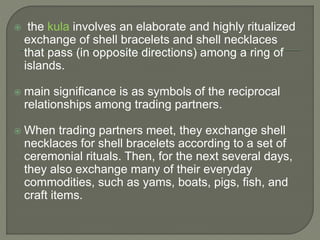

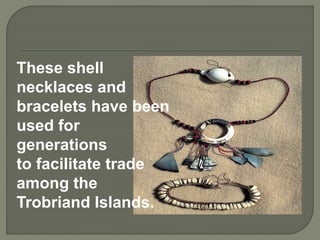

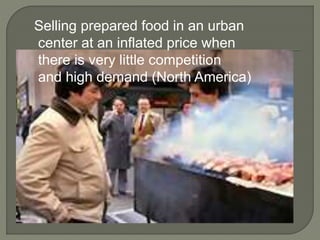

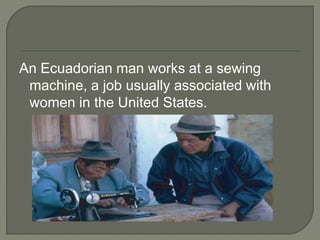

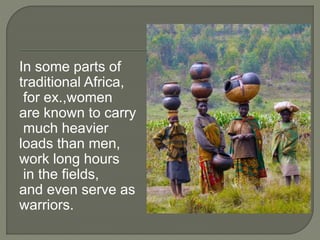

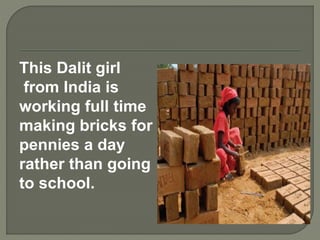

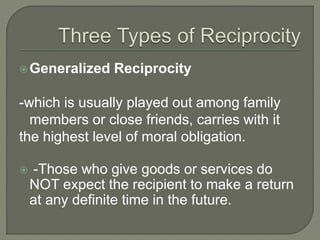

The document discusses different types of division of labor and distribution of goods and services across societies. It addresses gender specialization with tasks often divided based on perceptions of male and female physical abilities. It also discusses age specialization with roles and responsibilities changing as people age. Finally, it examines different modes of distributing goods and services, including reciprocity which ranges from generalized to balanced, redistribution, and market exchange.

![After having lived in Kandoka village in Papua New

Guinea on several different occasions, anthropologist

David Counts learned important lessons about life in a

society that practices reciprocity:

First, in a society where food is shared or gifted as

part of social life, you may not buy it with money. . . .

[Second,] never refuse a gift, and never fail to return

a gift. If you cannot use it, you can always give it to

someone else. . . .

[Third,] where reciprocity is the

rule and gifts are the idiom, you cannot demand a

gift, just as you cannot refuse a request.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/culturaleconomicsystem-180628011602/85/Cultural-economic-system-23-320.jpg)