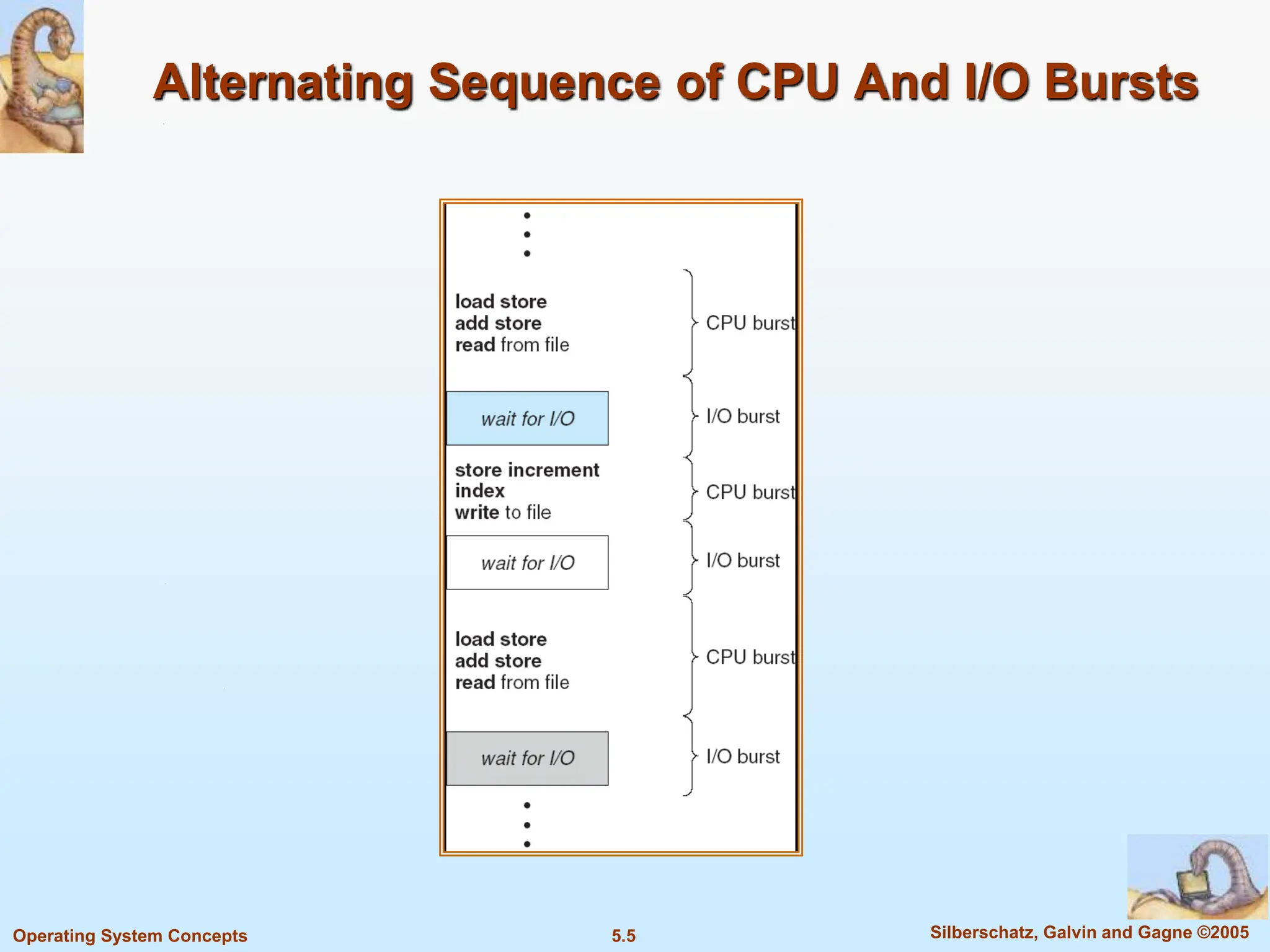

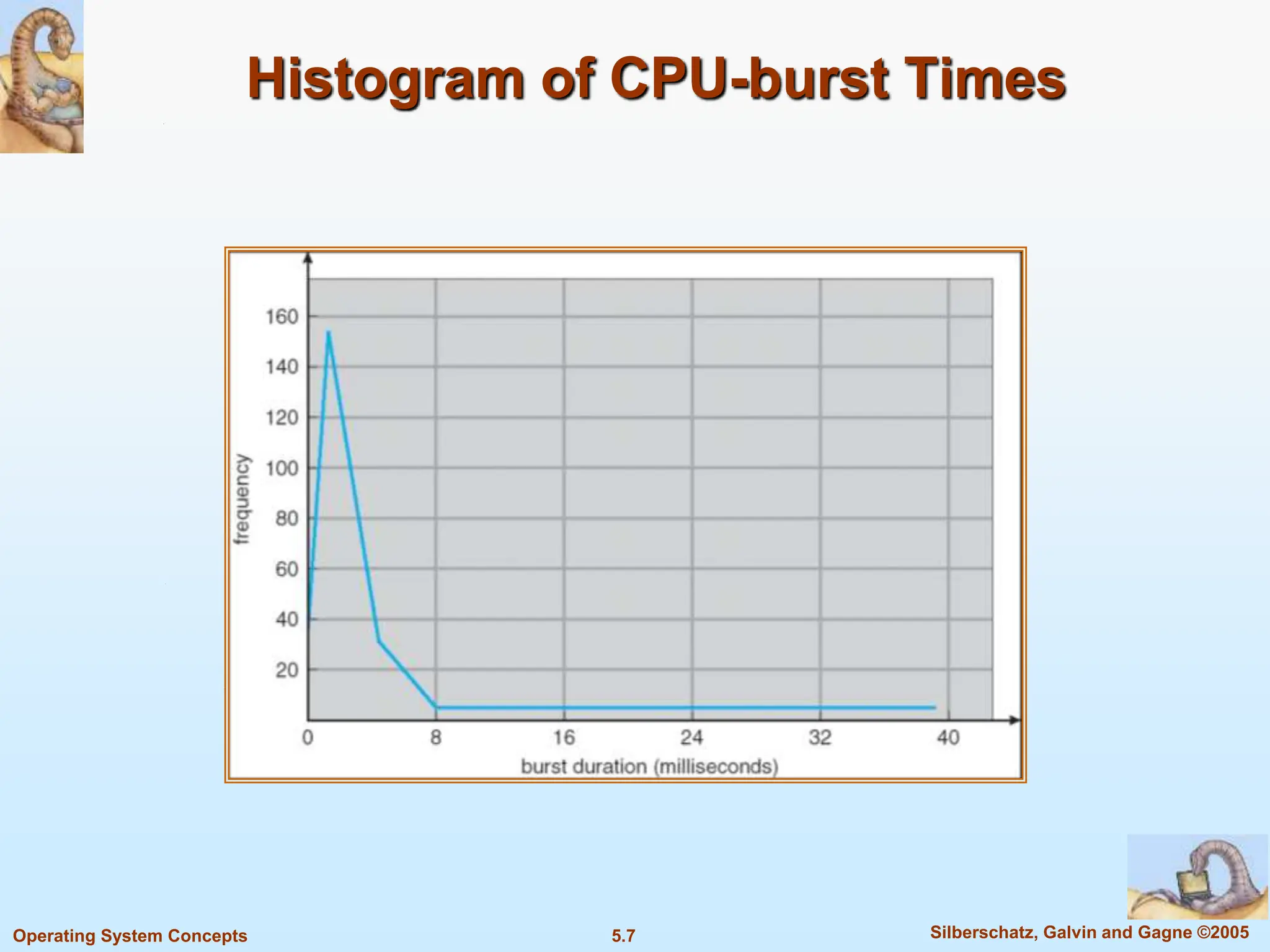

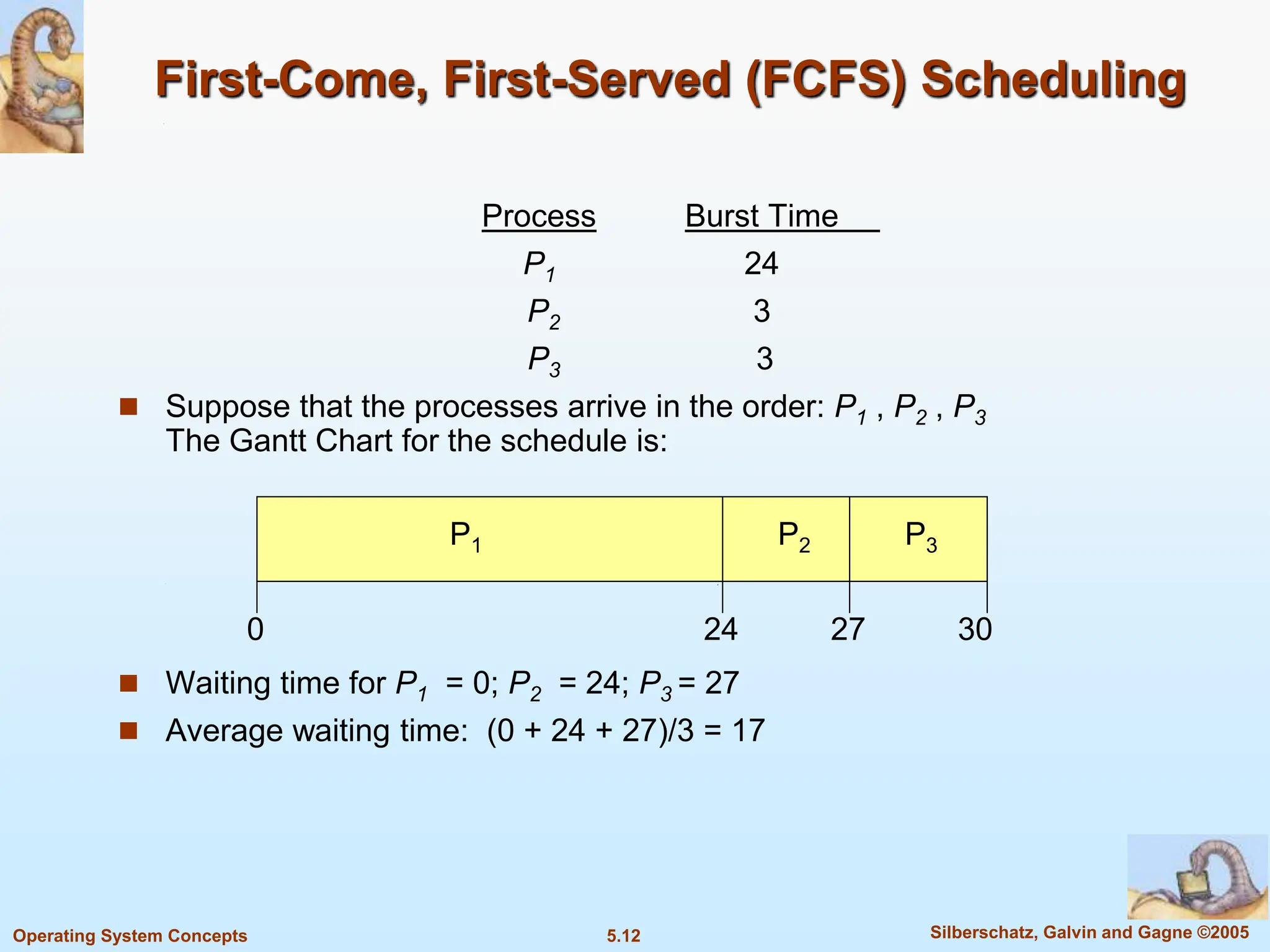

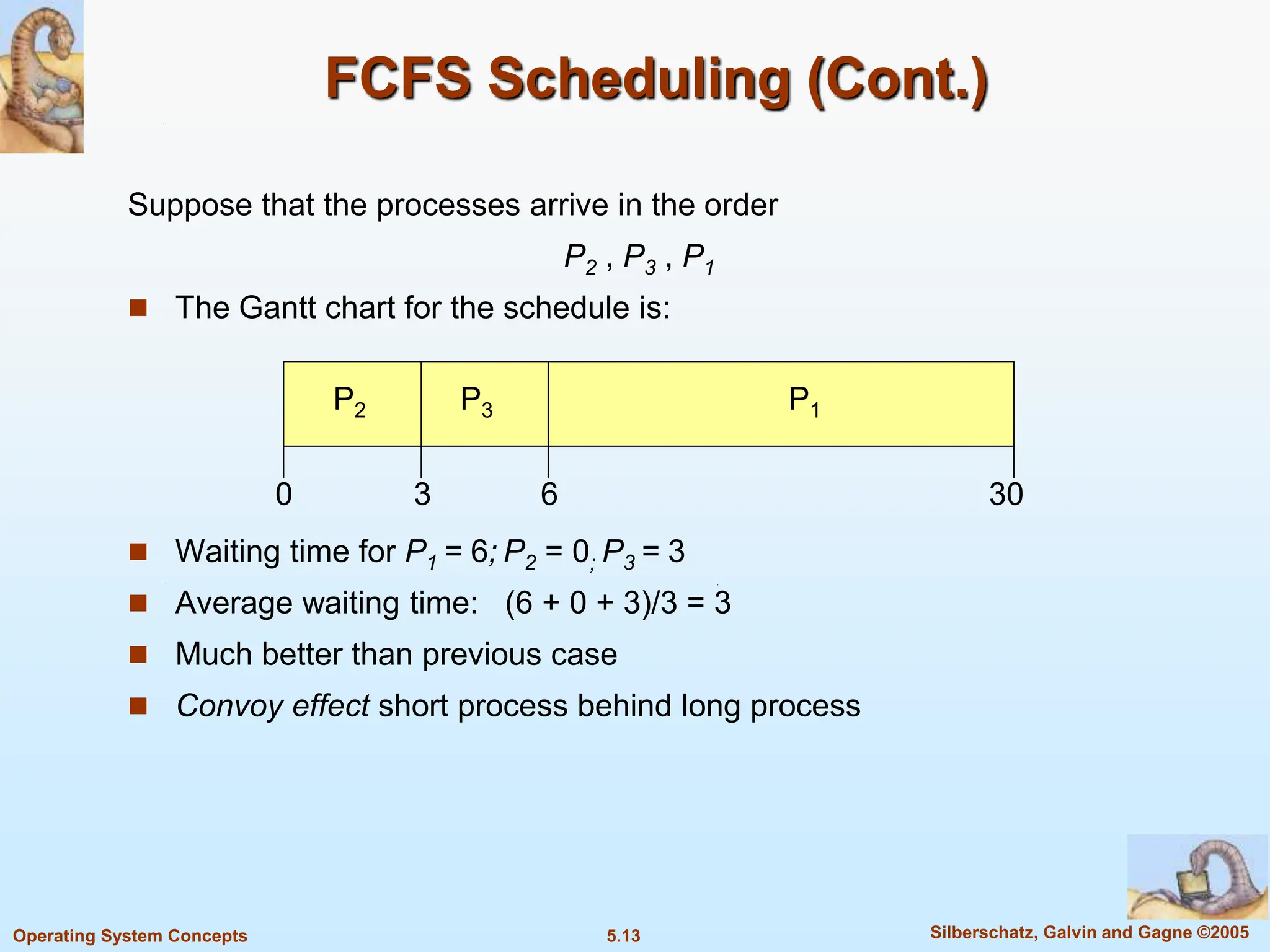

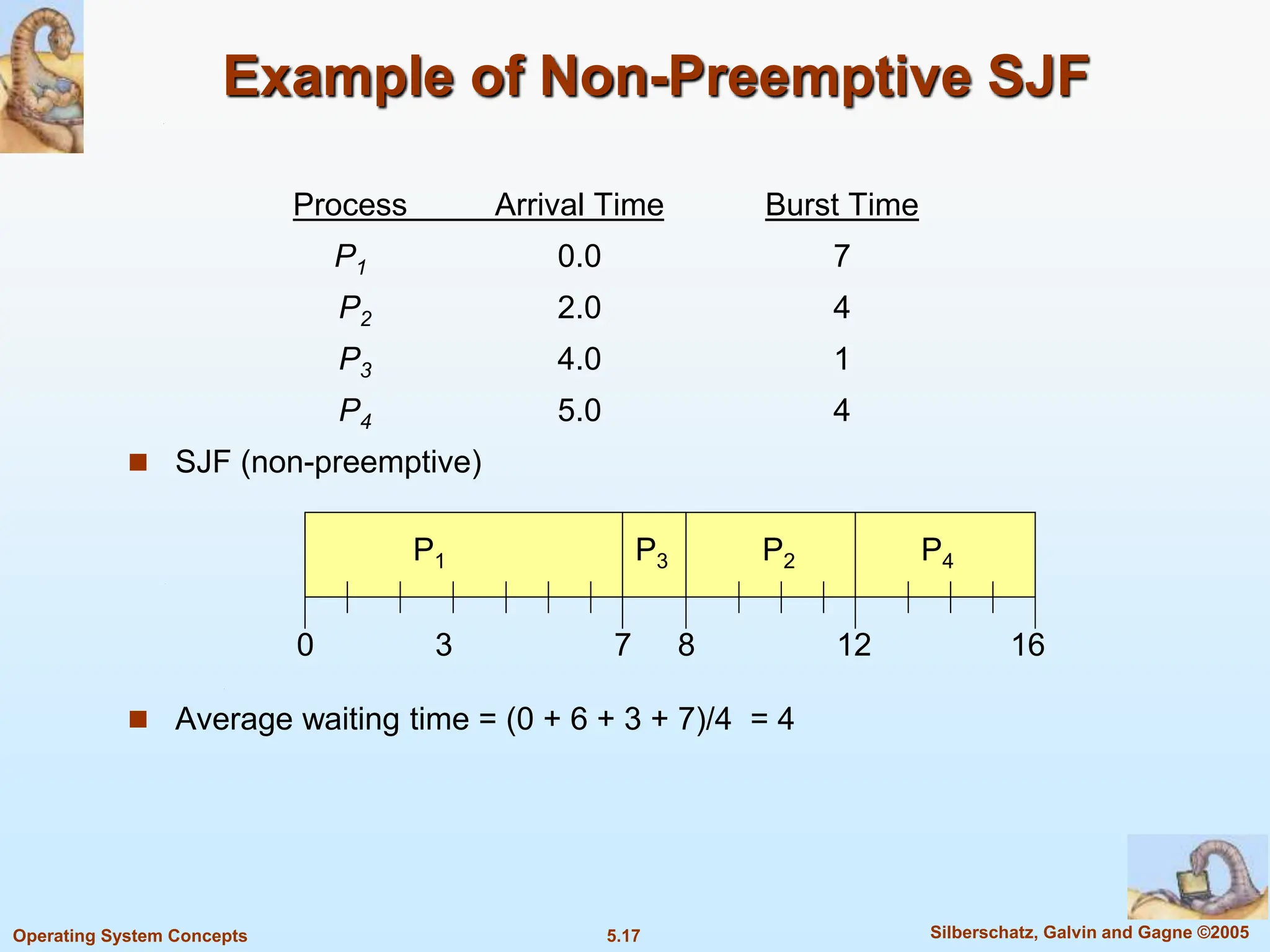

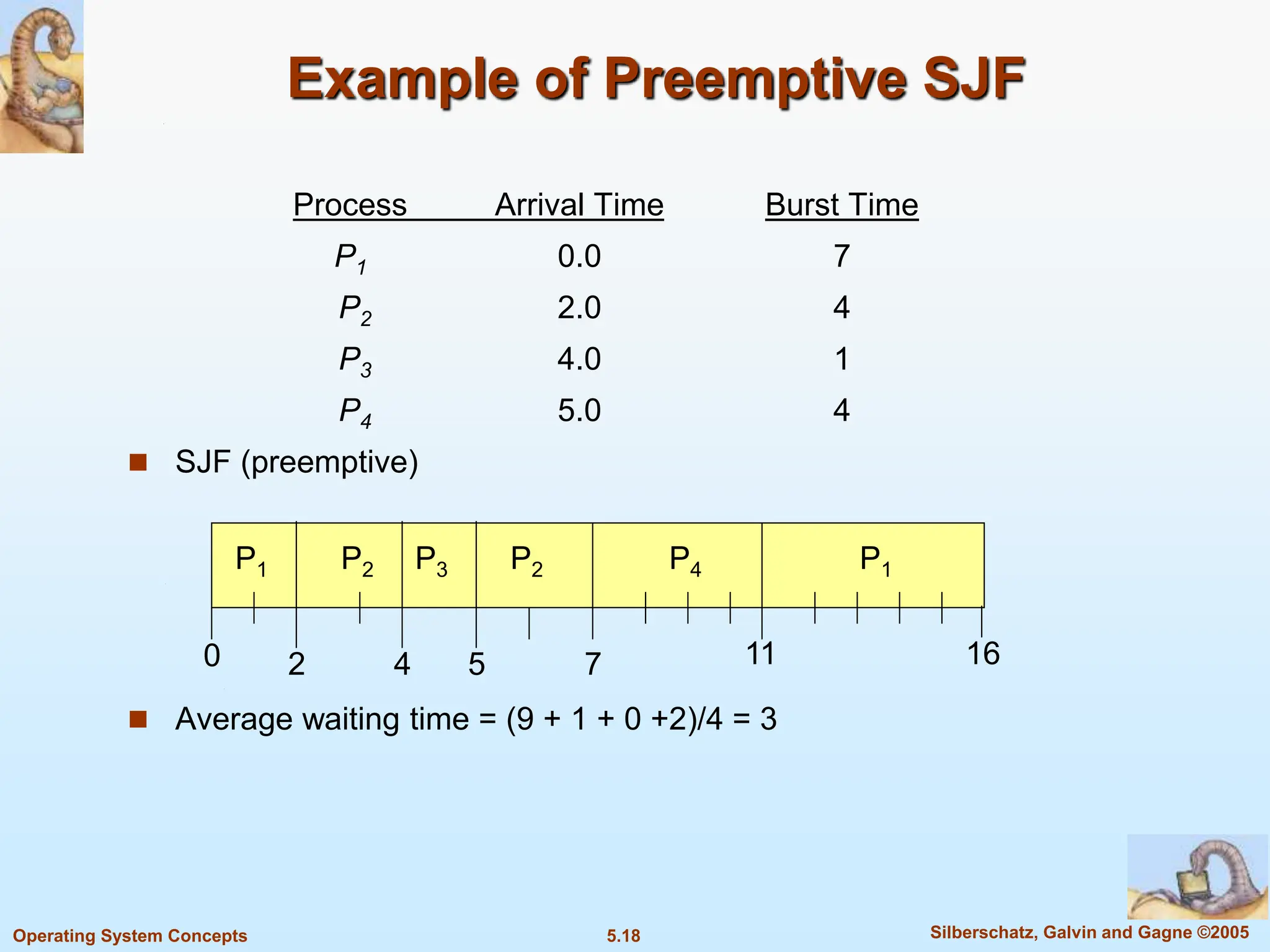

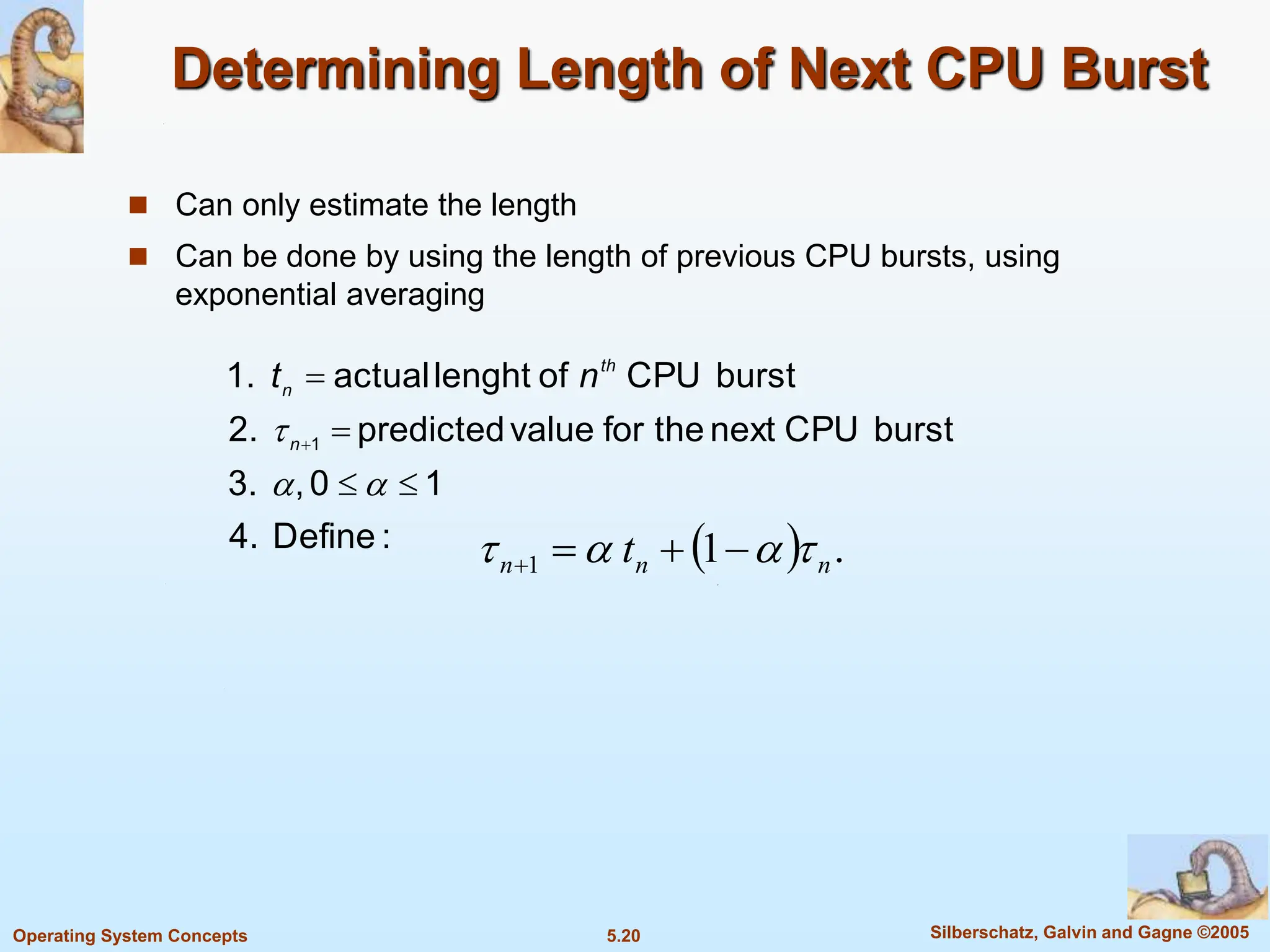

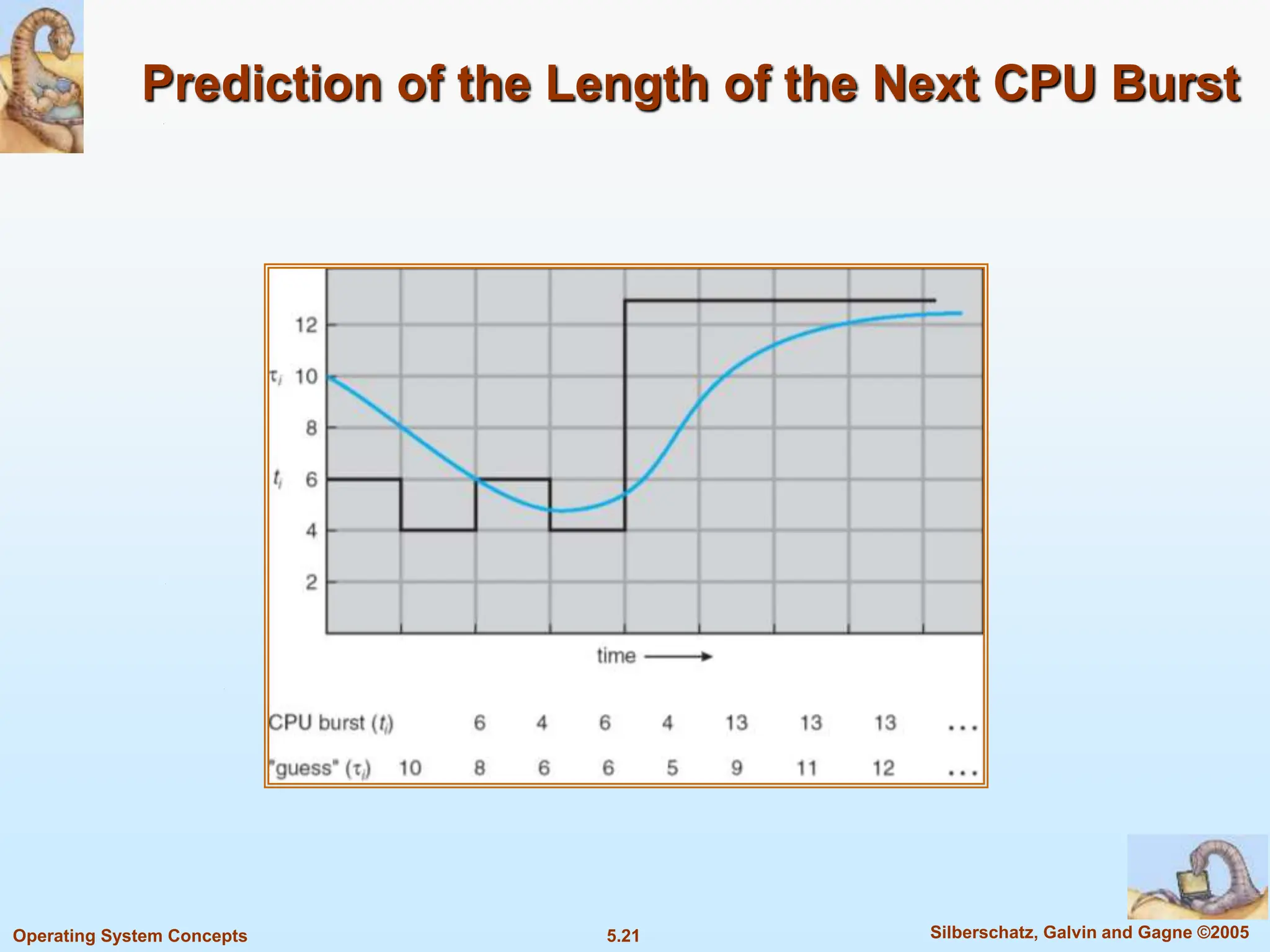

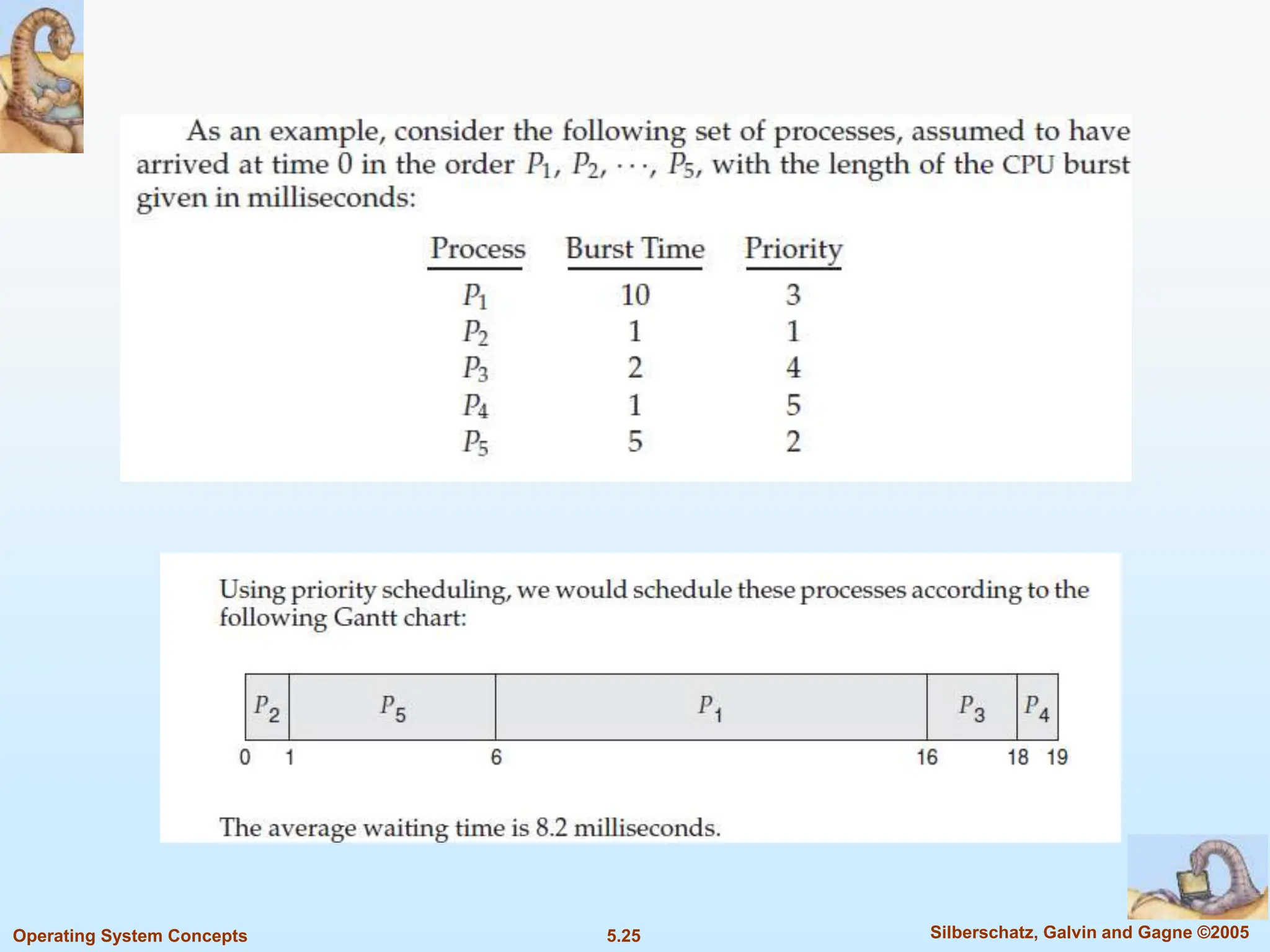

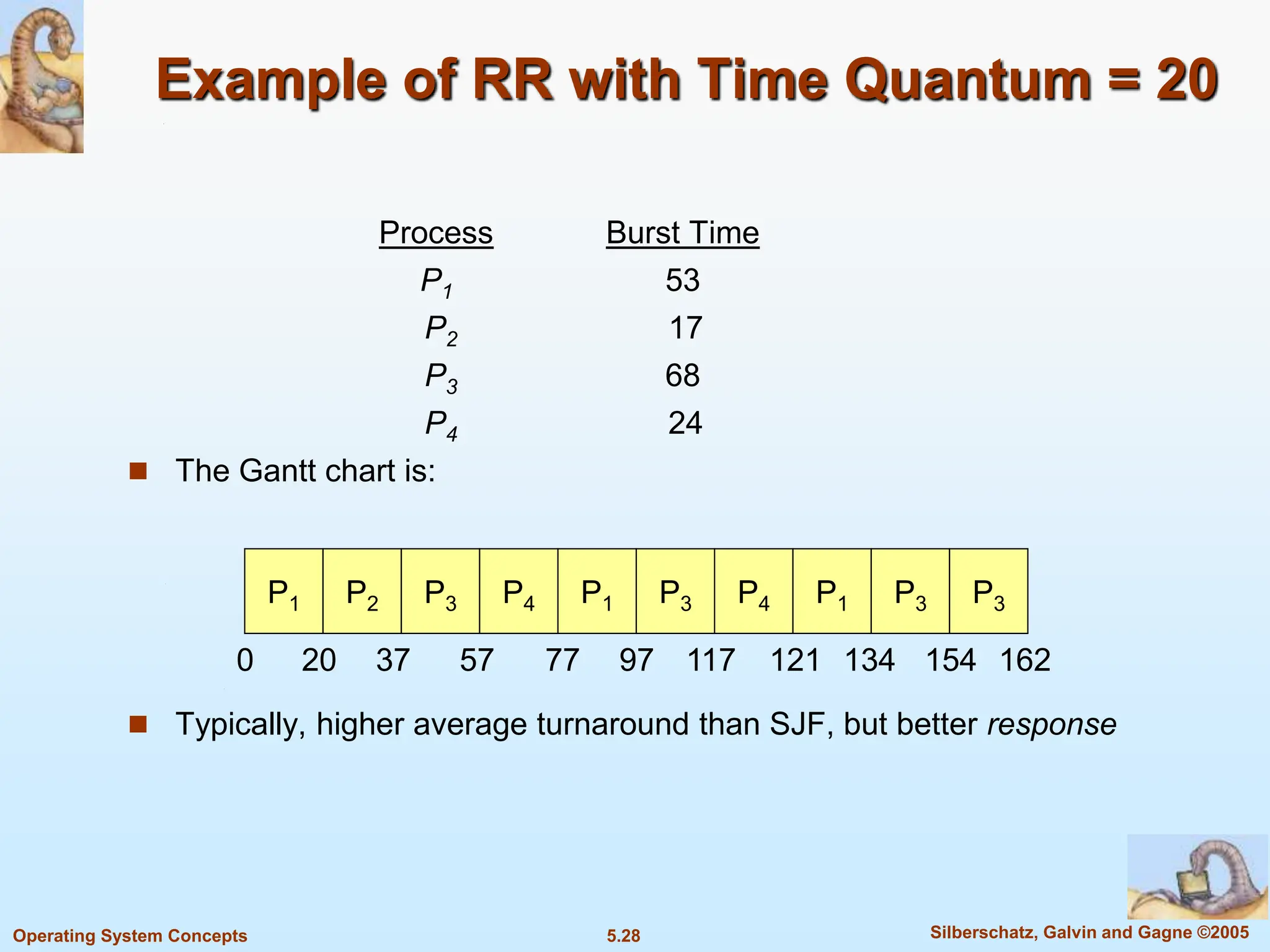

This document summarizes key concepts in CPU scheduling. It discusses the CPU-I/O burst cycle where processes alternate between CPU and I/O states. Common scheduling criteria like throughput and waiting time are described. First-come, first-served and shortest-job-first scheduling algorithms are explained. It also covers determining the length of the next CPU burst and priority scheduling approaches.