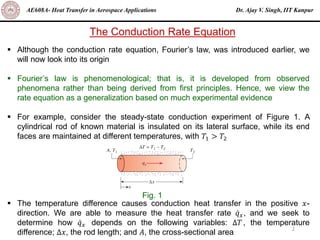

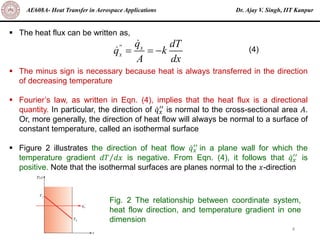

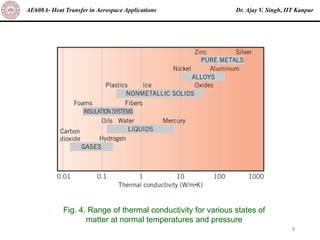

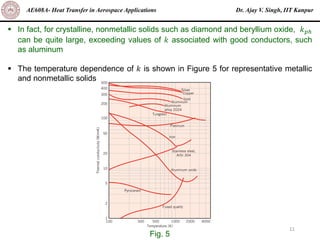

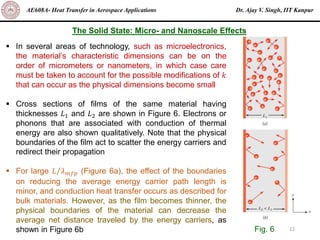

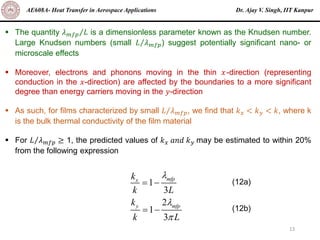

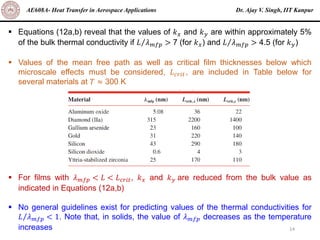

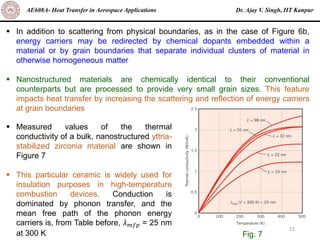

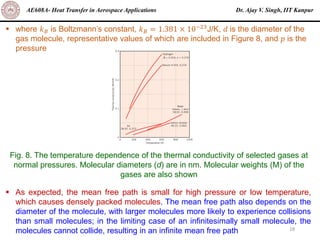

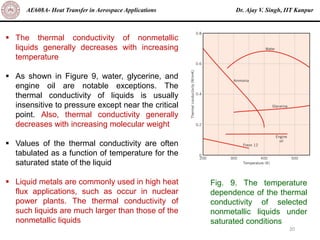

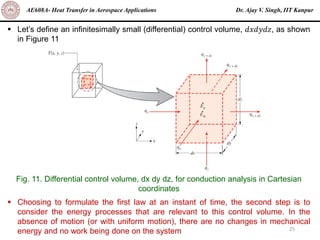

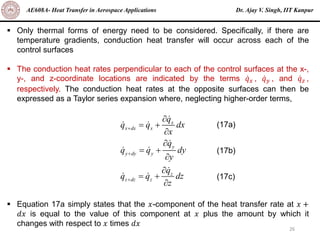

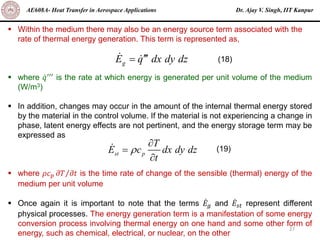

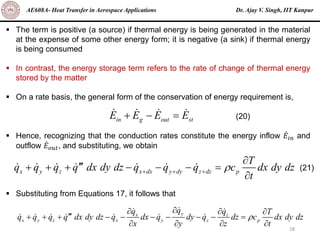

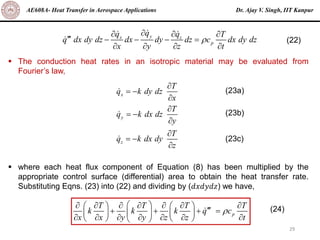

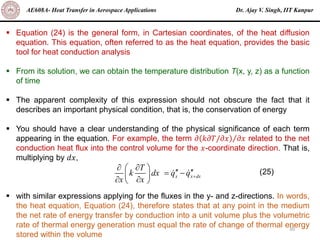

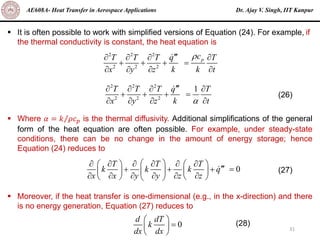

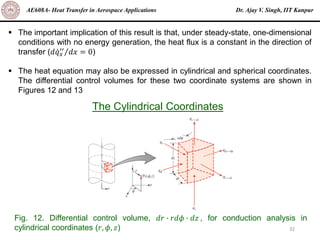

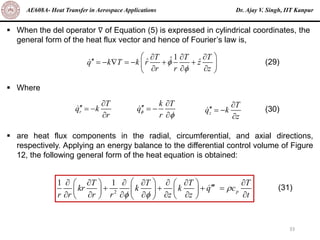

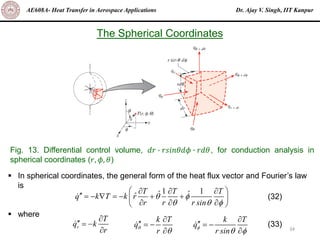

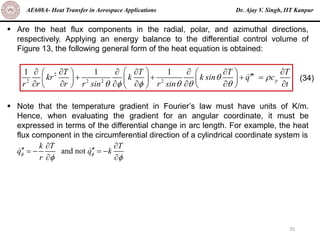

The document is a lecture on heat transfer by conduction from Dr. Ajay V. Singh of IIT Kanpur. It introduces Fourier's law of heat conduction and explains its origins from experimental evidence. It then discusses conduction rate equations and how they relate heat flux to temperature gradients and material properties like thermal conductivity. The document also covers the temperature and material dependencies of thermal conductivity and the effects of micro- and nano-scale sizes on thermal conductivity values.