Computational Methods in Biomedical Research 1st Edition Ravindra Khattree (Editor)

Computational Methods in Biomedical Research 1st Edition Ravindra Khattree (Editor)

Computational Methods in Biomedical Research 1st Edition Ravindra Khattree (Editor)

![C5777: “c5777_c001” — 2007/10/27 — 13:02 — page 17 — #17

Microarray Data Analysis 17

where Di represents the selected measure of dispersion for the ith array and

D. is the mean, median, or maximum of the Di values over all arrays. If the

IQR is used, all arrays will have approximately the same IQR after adjust-

ment. Quasi-ranges other than the IQR (which is based on the 25th and 75th

percentiles) could be used. For example, the normal range is based on the

2.5th and 97.5th percentiles.

1.3.2.3 Local Regression Methods

The M vs. A (MvA) plot (Dudoit et al., 2002) is a graphic tool to visualize

variability as a function of average intensity. This plots values of M (differ-

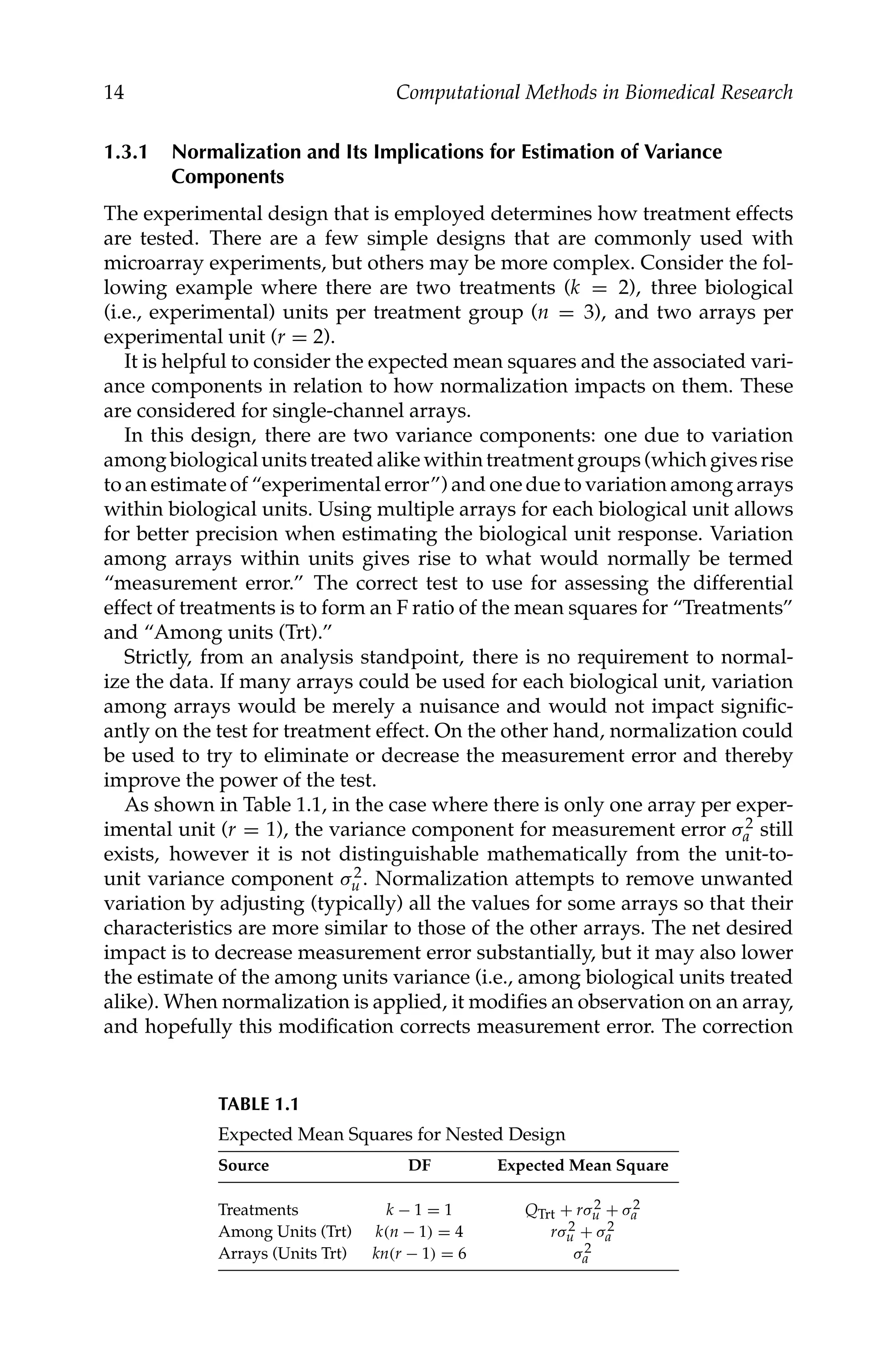

ence of logs) vs. A (average of logs) for paired values. These are defined

mathematically as

Mj = log2(y

(1)

ij ) − log2(y

(2)

ij ) and Aj =

[log2(y

(1)

ij ) + log2(y

(2)

ij )]

2

for array i and gene (or probe) j. With two-channel arrays, the pairing is based

on the data from the same spot corresponding to the red and green dyes.

A loess smoothing function is fitted to the resulting data. Normalization is

accomplished by adjusting each expression value on the basis of deviations,

as follows:

log2(y

(1)∗

ij ) = Aj + 0.5 M

j and log2(y

(2)∗

ij ) = Aj − 0.5 M

j

where M

j represents the deviation of the jth gene from the fitted line. This is

a within-array normalization.

The MvA plot can be used in single-channel arrays by forming all pairs of

arrays to generate MvA plots; this method is known as cyclic loess (Bolstad

et al., 2003). The proposed algorithm produces normalized values through

an iterative algorithm. This approach is not computationally attractive for

experiments involving a large number of arrays.

1.3.2.4 Quantile-Based Methods

Quantile normalization forces identical distributions of probe intensities for

all arrays (Bolstad et al., 2003; Irizarry et al., 2003a; Irizarry et al., 2003c;

Irizarry et al., 2003b). The following steps may be used to implement this

method: (1) All the probe values from the n arrays are formed into a p × n

matrix (p = total number of probes on each array and n = number of arrays),

(2) Each column of values is sorted from lowest to highest value, (3) The values

in each row are replaced by the mean of the values in that row, (4) The elements

of each column are placed back into the original ordering. The modified probe

values are used to calculate normalized expression values.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/57692-250301181146-19dc94ff/75/Computational-Methods-in-Biomedical-Research-1st-Edition-Ravindra-Khattree-Editor-41-2048.jpg)