Exposureresponse Modeling Methods And Practical Implementation 1st Edition Jixian Wang

Exposureresponse Modeling Methods And Practical Implementation 1st Edition Jixian Wang

Exposureresponse Modeling Methods And Practical Implementation 1st Edition Jixian Wang

![Basic exposure and exposure–response models 25

approach (TBS, Carroll and Ruppert, 1988). Typically a log TBS is a bridge

between additive and multiplicative models. One reason for using a transfor-

mation from a statistical aspect is to make the distribution of the response

easy to handle with a simple model. The log-transformation is the most com-

mon one to use. The transformation also converts a multiplicative model to

an additive one, and the latter is often much easier to fit. Some transforma-

tions proposed from purely statistical aspects, particularly those depending

on extra-parameters, such as the Box–Cox transformation, are used less fre-

quently than the log-transformation in ER modeling. Here we will mainly

focus on the log-transformation.

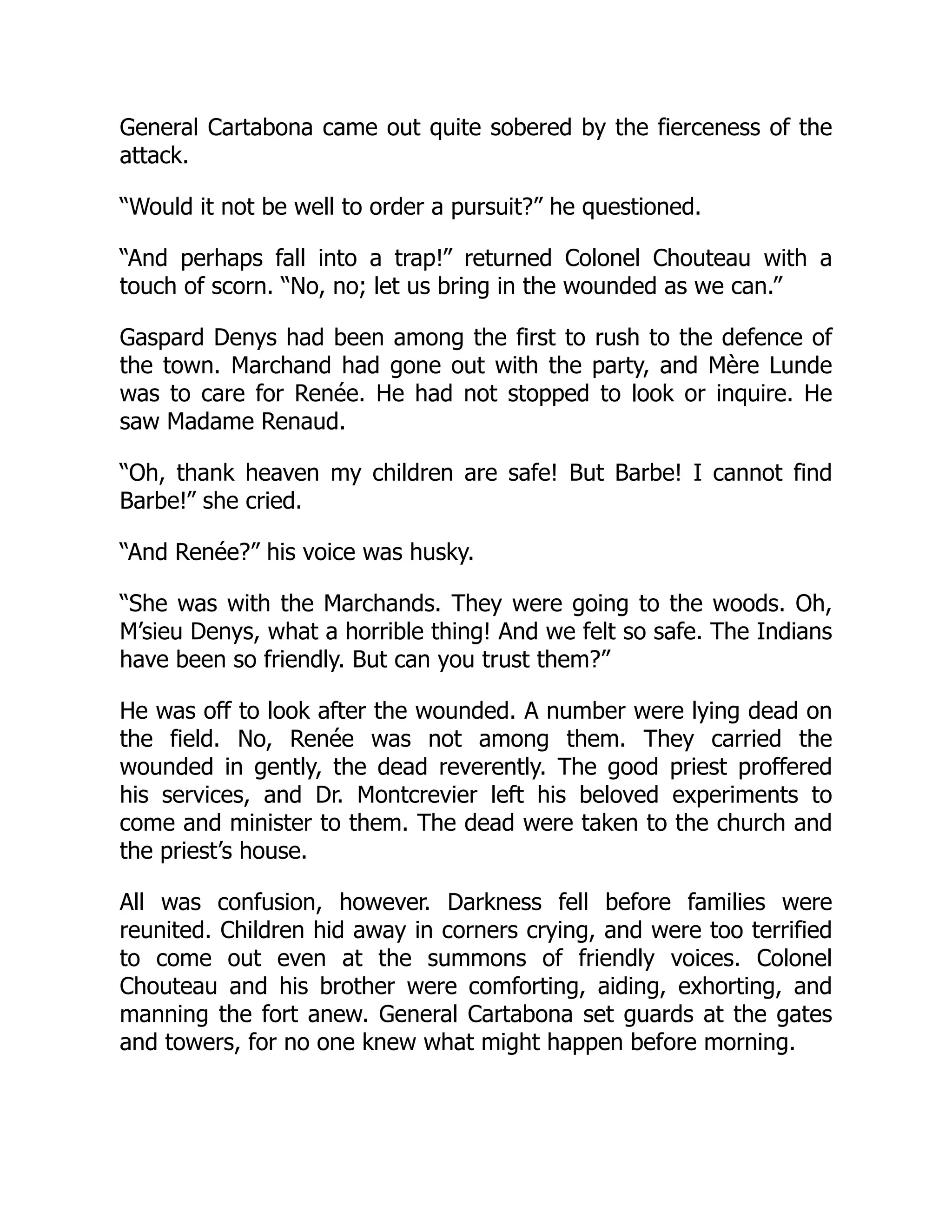

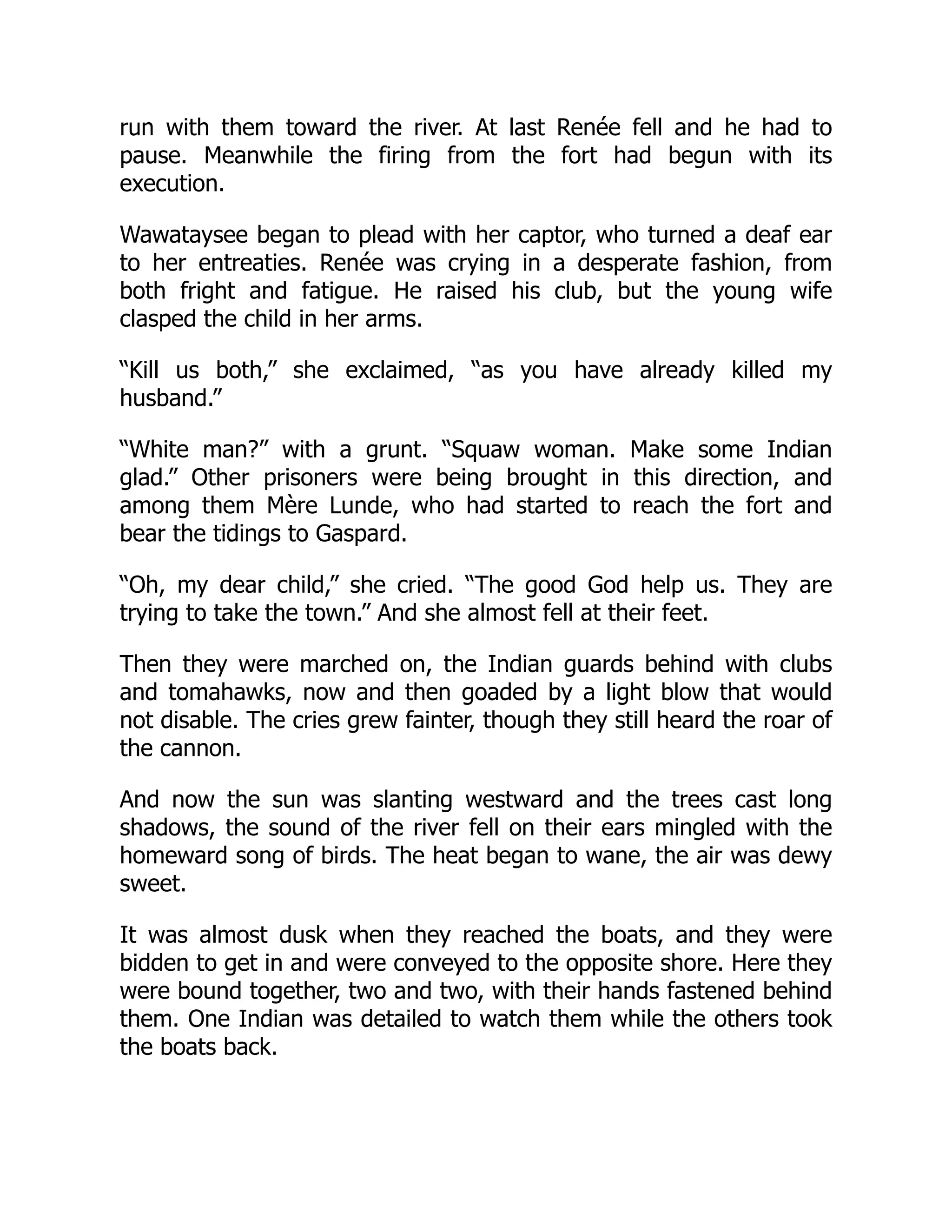

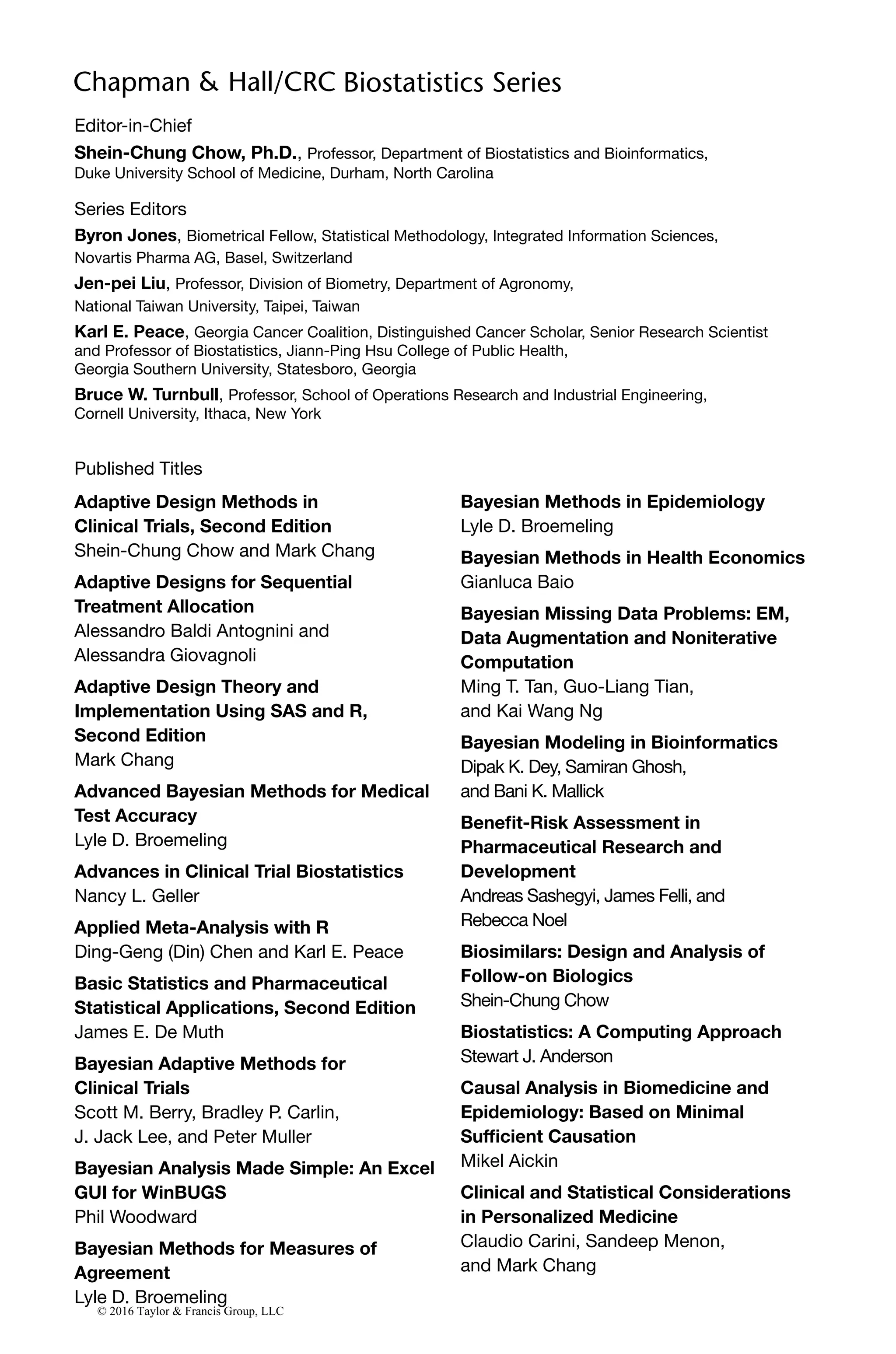

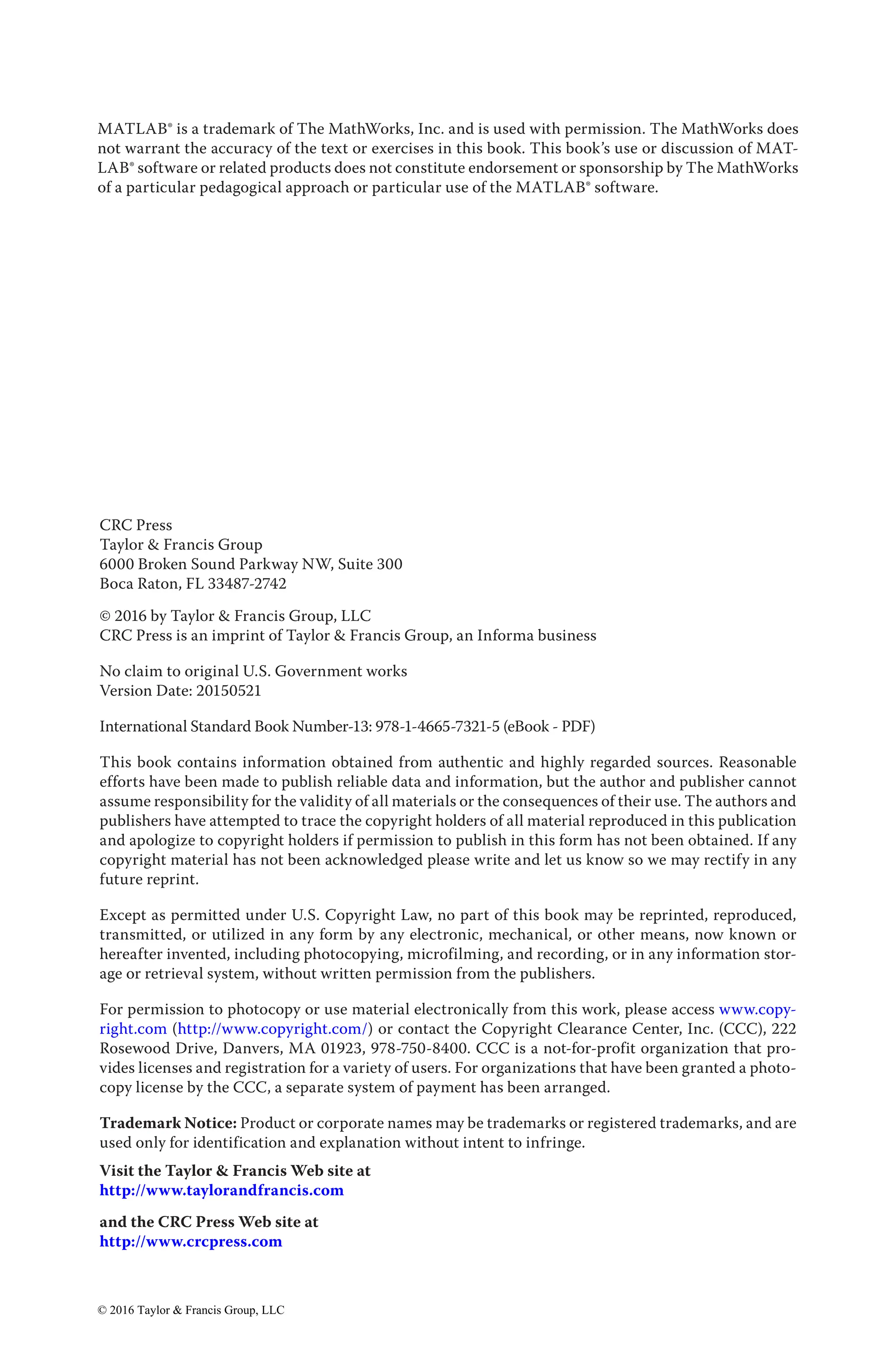

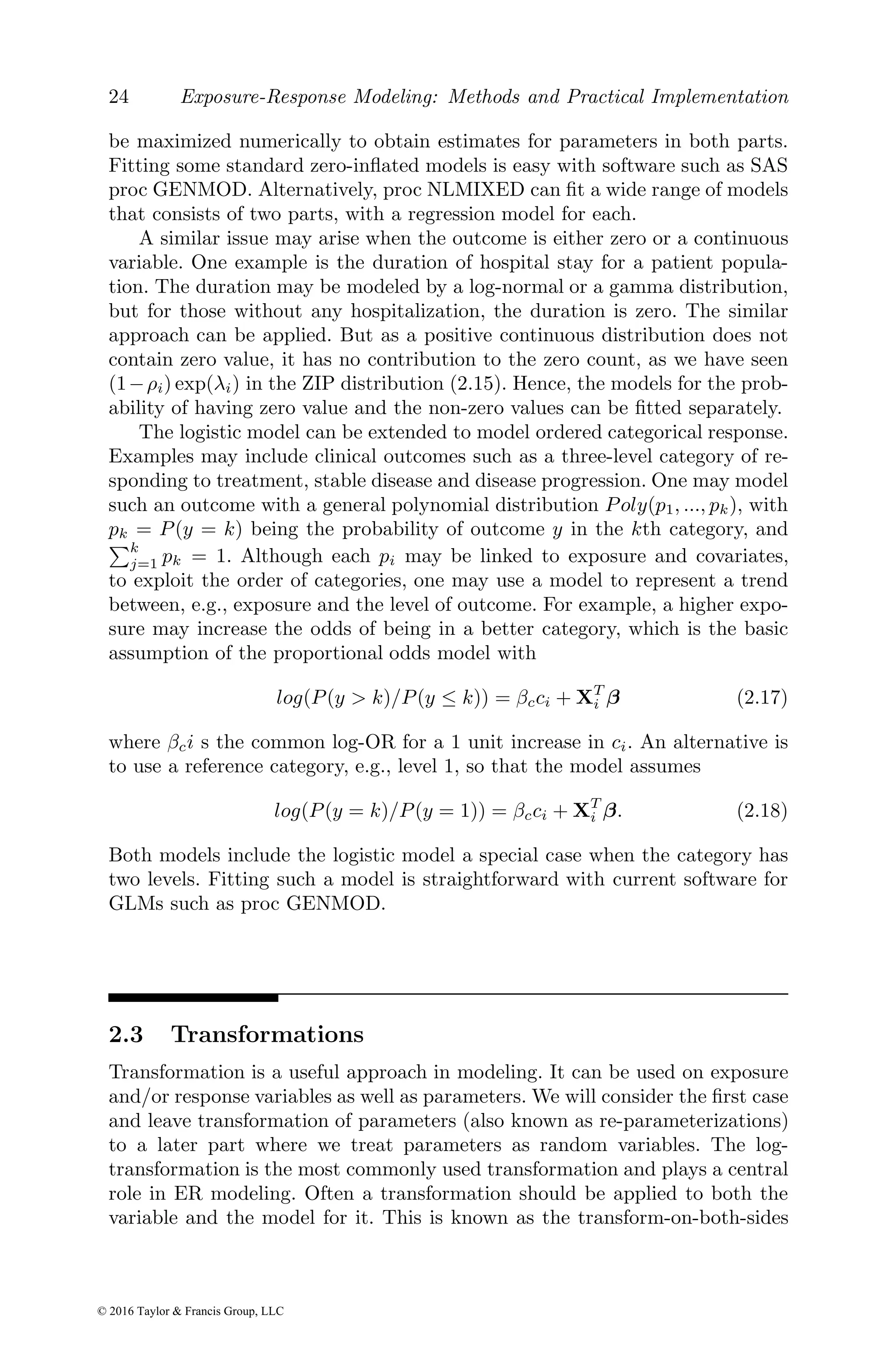

Consider the theophylline concentration data. Since there is no dosing

history data, we model the concentration data before any dose adjustment is

made. Let ci be the concentration from patient i at 0.01 h. We fitted a linear

model for log-transformed ci and covariates:

log(ci) = XT

i β + ei, (2.19)

where ei ∼ N(0, σ2

e). Note that this model might be considered as an approx-

imation to model (2.6). The data were fitted by the linear regression function

lm(.) in R. After fitting models with different combinations of covariates in

Xi, we found that only age is related to ci (denoted as THEO in the outputs)

and the fitted model is

lm(formula = log(THEO) ~ log(AGE), data = short[short$TIME ==0.01, ])

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -0.8623 0.9418 -0.916 0.3618

log(AGE) 0.5699 0.2655 2.147 0.0339

The other factors included in the dataset might have been sufficiently adjusted

when planning the initial dose. Transforming back to the original scale, we get

the geometric mean of ci as

exp(XT

i β̂) = exp(−0.862)AGE0.570

(2.20)

which is in the form of the power model. The key feature is that the contri-

butions of the factors are multiplicative to each other. Note that Eg

(yi) =

exp(XT

i β) is the geometric mean of yi and E(yi) = exp(XT

i β)E(exp(ei)) >

exp(XT

i β). Geometric means are commonly used for modeling exposure data,

but may not always be appropriate for PKPD modeling.

Transformations are also used for nonlinear models. The error structure of

the model is a key factor to consider for selecting an appropriate transforma-

tion. We take the Emax model (2.3) as an example to show how to select the

transformation. Suppose that yi is positive (e.g., the tumor size or a positive

valued biomarker) and its relationship with ci has a sigmoid-like shape; then

the following model may be considered:

log(yi) = log(Emax/(1 + EC50/ci)εi)

= log(Emax) − log(1 + EC50/ci) + log(εi) (2.21)

© 2016 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2645101-250722182738-ee90be60/75/Exposureresponse-Modeling-Methods-And-Practical-Implementation-1st-Edition-Jixian-Wang-47-2048.jpg)

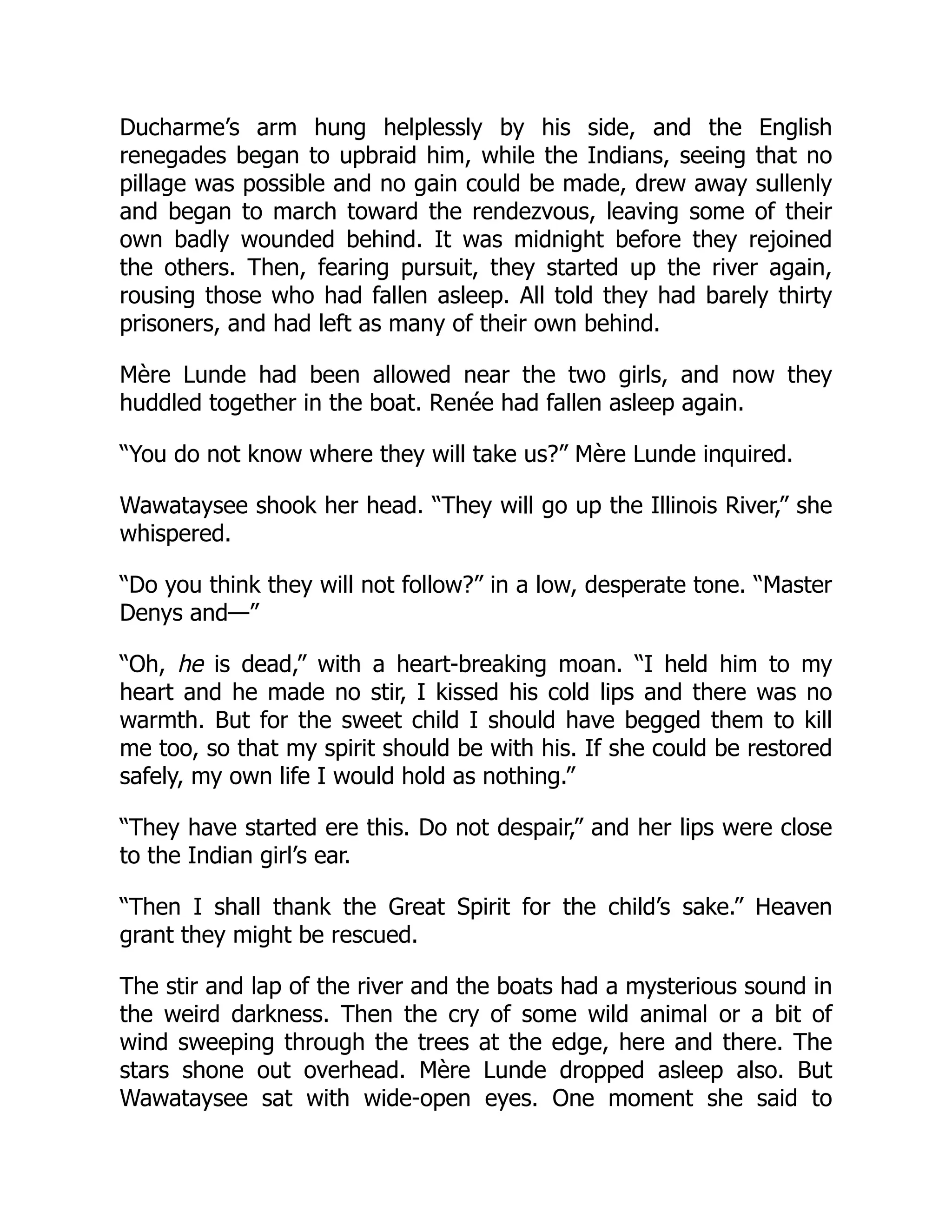

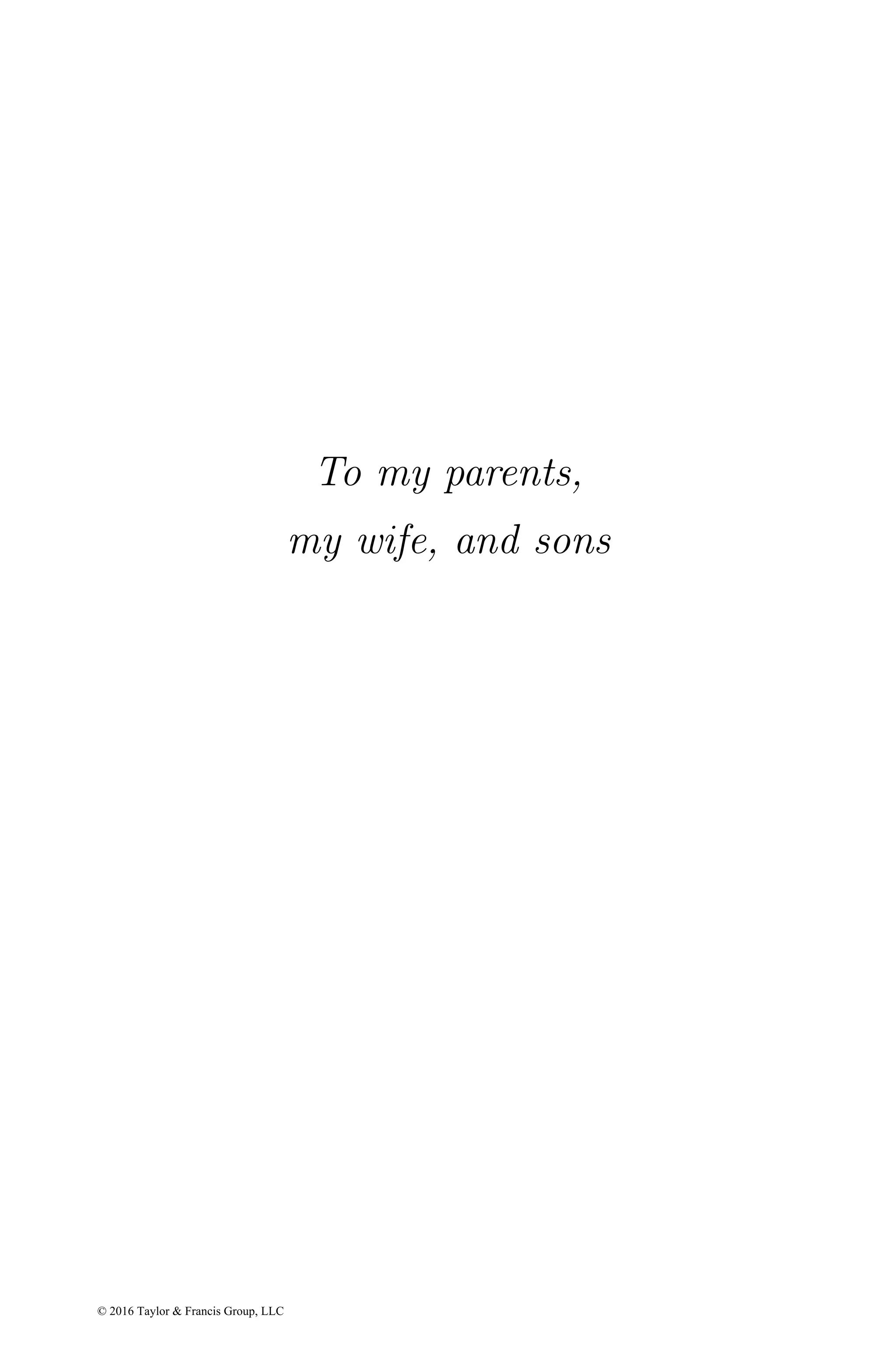

![28 Exposure-Response Modeling: Methods and Practical Implementation

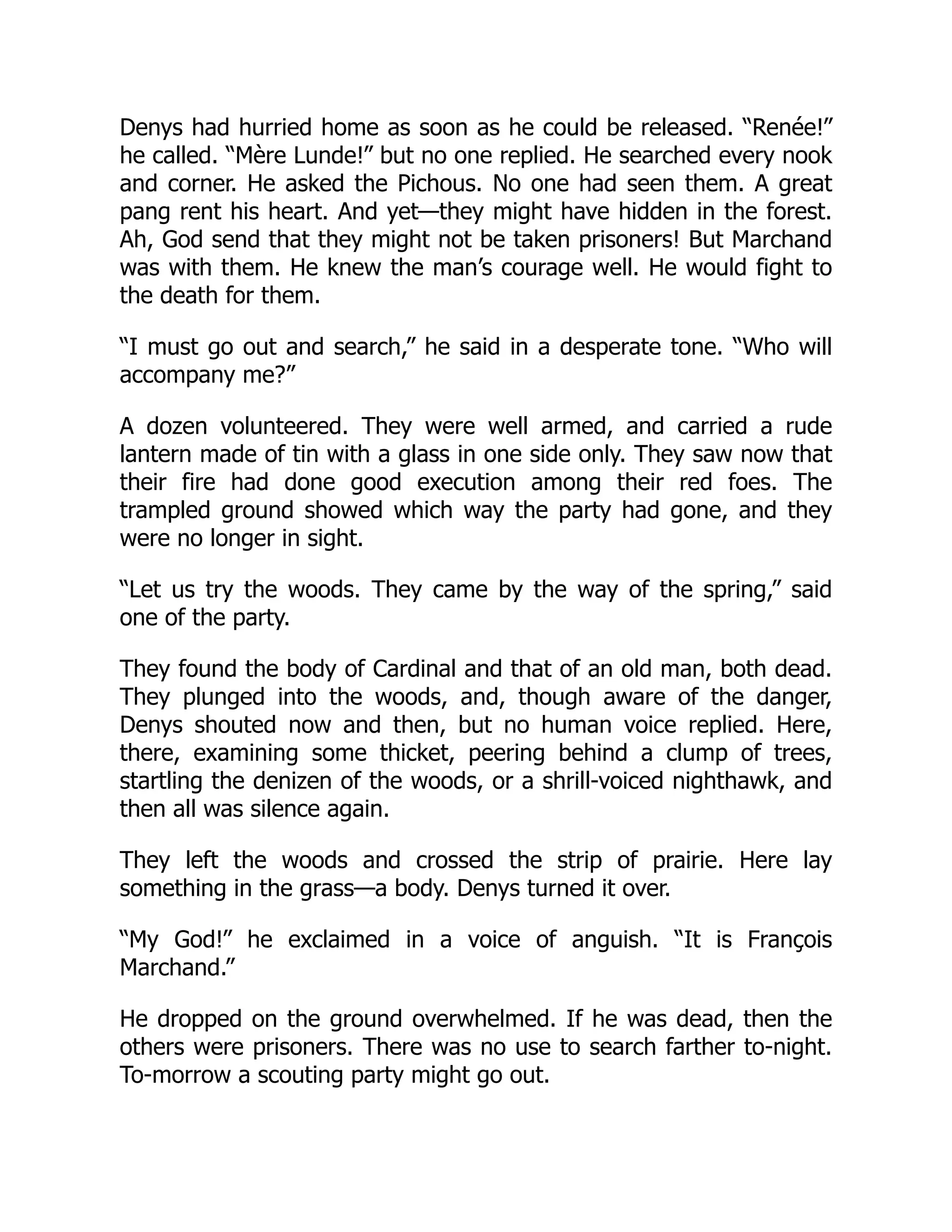

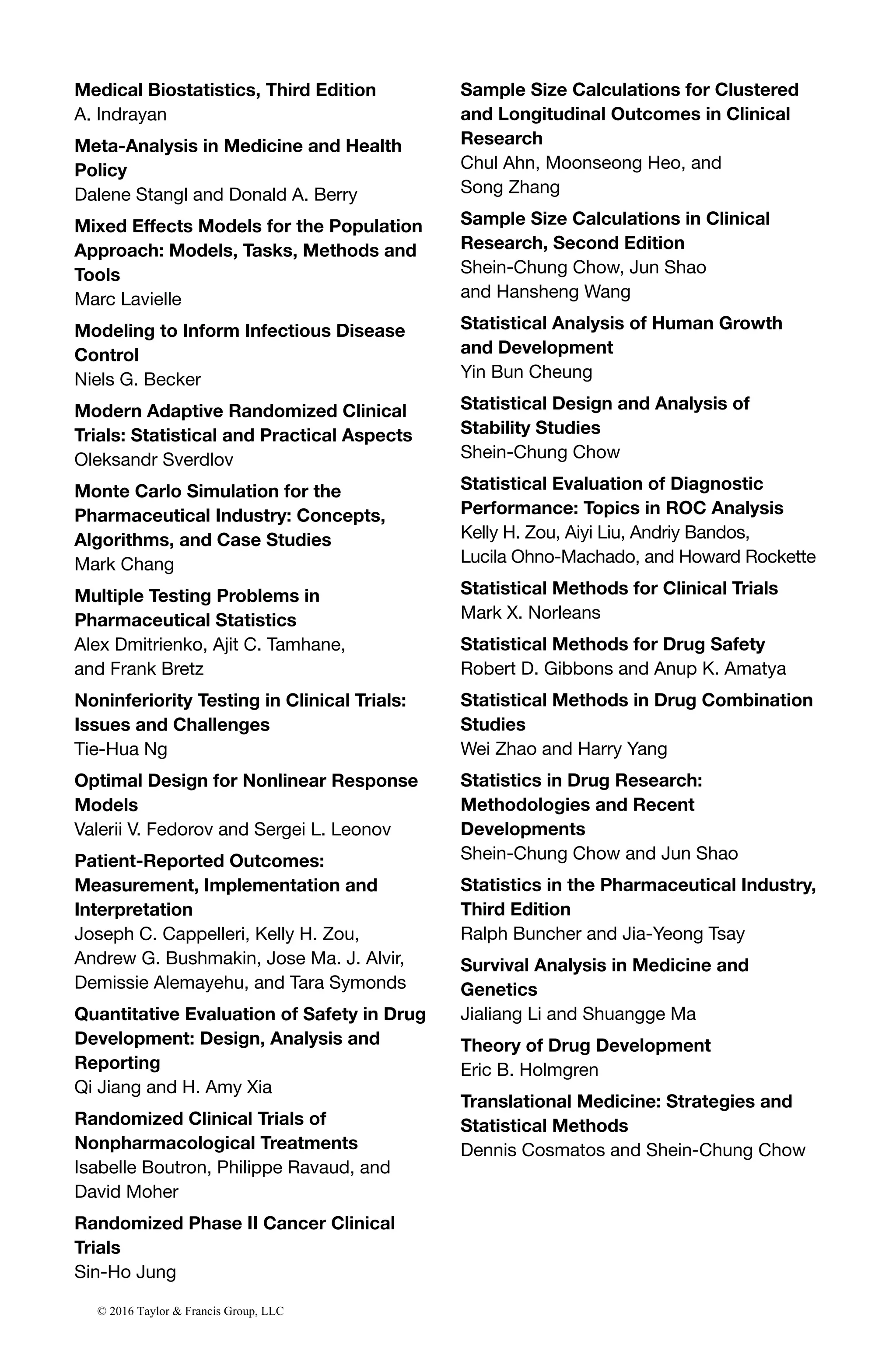

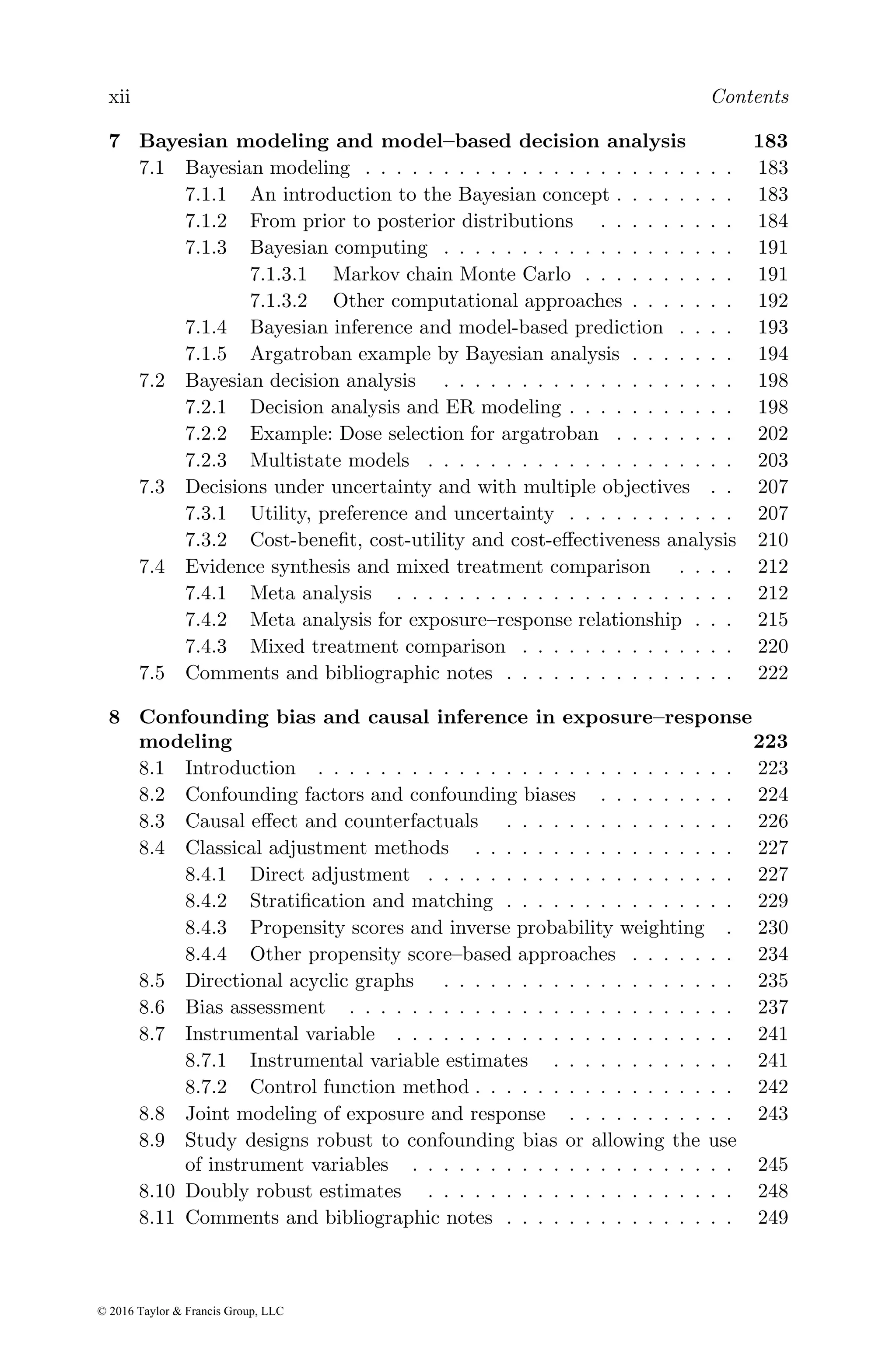

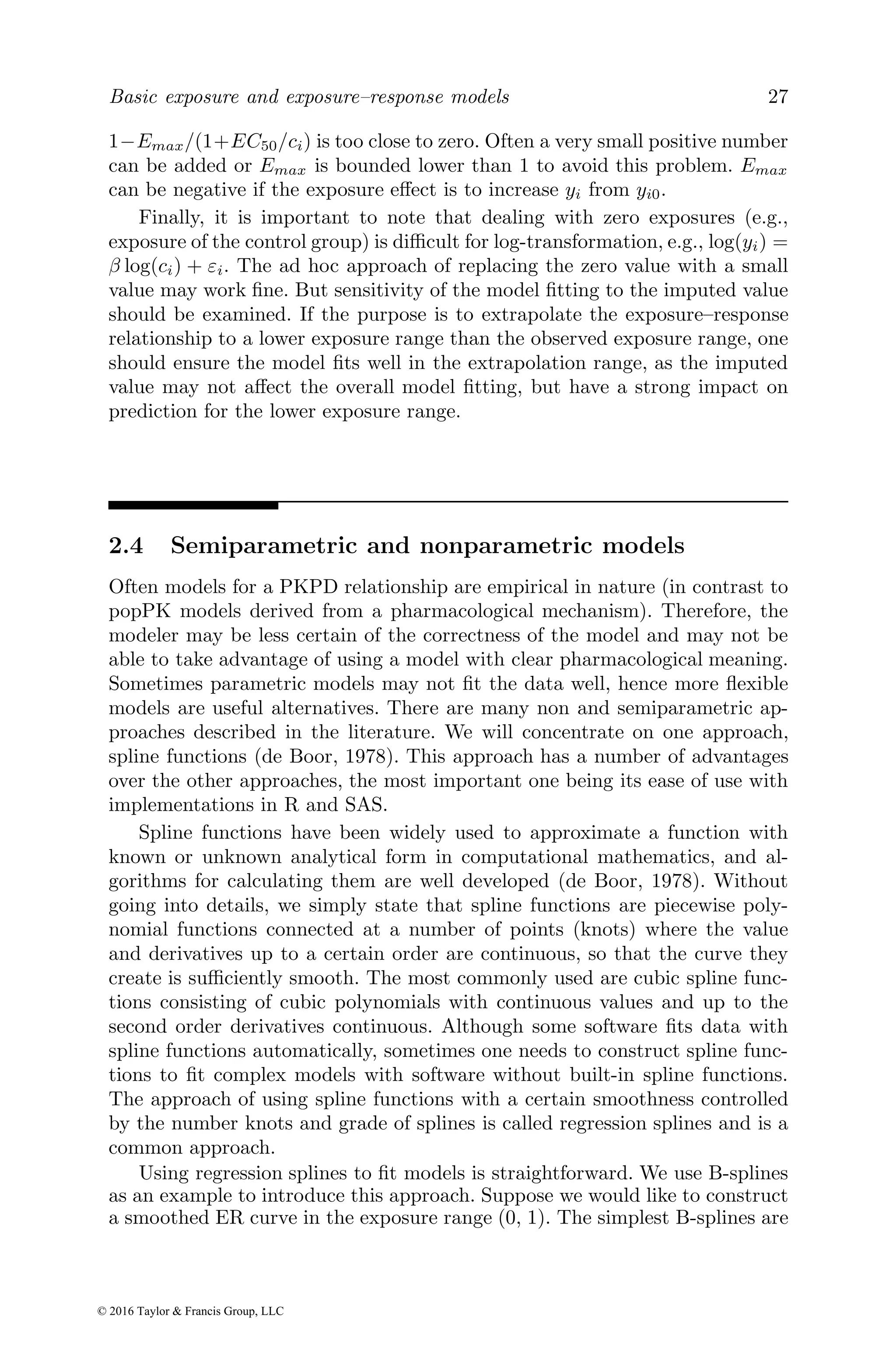

those with knots at 0 and 1 only (known as boundary knots). In this case,

the B-splines are terms of Ck

nxn

(1 − x)k

, k = 0, ..., n, with Ck

n the number of

combinations of taking k balls from a total of n. With only boundary knots,

the cubic B-spline has n = 3 + 1 = 4 such terms. Using function bs() in R

library splines, we can construct

> x=(0:10)/10

> cbind(x,bs(x,degree = 3,intercept=T))

x 1 2 3 4

[1,] 0.0 1.000 0.000 0.000 0.000

[2,] 0.1 0.729 0.243 0.027 0.001

[3,] 0.2 0.512 0.384 0.096 0.008

[4,] 0.3 0.343 0.441 0.189 0.027

[5,] 0.4 0.216 0.432 0.288 0.064

[6,] 0.5 0.125 0.375 0.375 0.125

[7,] 0.6 0.064 0.288 0.432 0.216

[8,] 0.7 0.027 0.189 0.441 0.343

[9,] 0.8 0.008 0.096 0.384 0.512

[10,] 0.9 0.001 0.027 0.243 0.729

[11,] 1.0 0.000 0.000 0.000 1.000

gives the function values at different x. With one interior knot at 0.5, there is

one more term

> bs(x,degree = 3,knots=0.5,intercept=T)

1 2 3 4 5

[1,] 1.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000

[2,] 0.512 0.434 0.052 0.002 0.000

[3,] 0.216 0.592 0.176 0.016 0.000

[4,] 0.064 0.558 0.324 0.054 0.000

[5,] 0.008 0.416 0.448 0.128 0.000

[6,] 0.000 0.250 0.500 0.250 0.000

[7,] 0.000 0.128 0.448 0.416 0.008

[8,] 0.000 0.054 0.324 0.558 0.064

[9,] 0.000 0.016 0.176 0.592 0.216

[10,] 0.000 0.002 0.052 0.434 0.512

[11,] 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 1.000

attr(,"degree")

[1] 3

attr(,"knots")

[1] 0.5

attr(,"Boundary.knots")

[1] 0 1

However, one of the terms is redundant as it is a linear combination of the

others. This can be seen from that Ck

nxn

(1−x)k

s are the probability of having

k events in n trials when x is the probability, hence

Pn

k=1 Ck

nxn

(1 − x)k

= 1.

Therefore, to fit B-splines to, e.g.,

√

x, one should use the bs() function without

the option intercept= T , which is the default, of not produce the first term:

© 2016 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2645101-250722182738-ee90be60/75/Exposureresponse-Modeling-Methods-And-Practical-Implementation-1st-Edition-Jixian-Wang-50-2048.jpg)

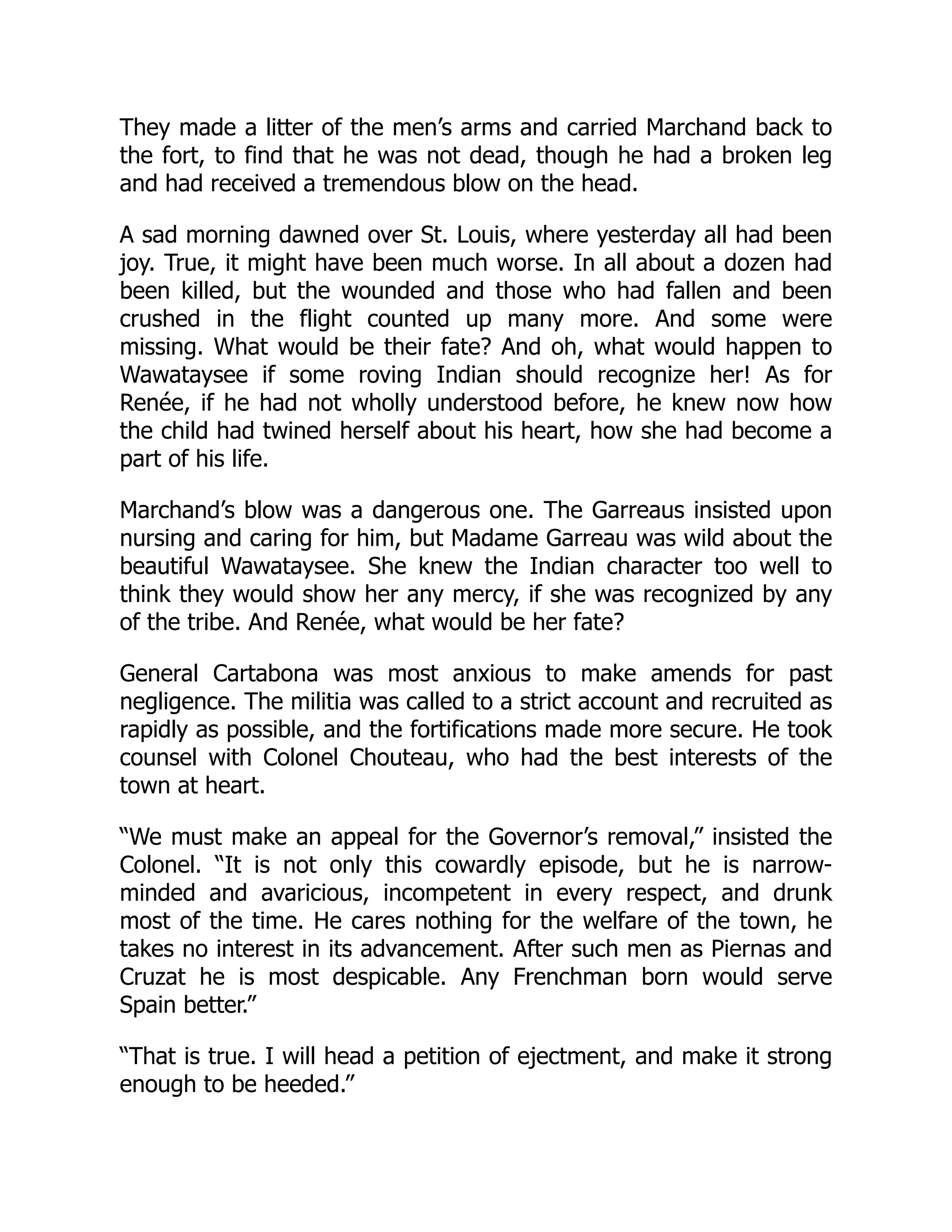

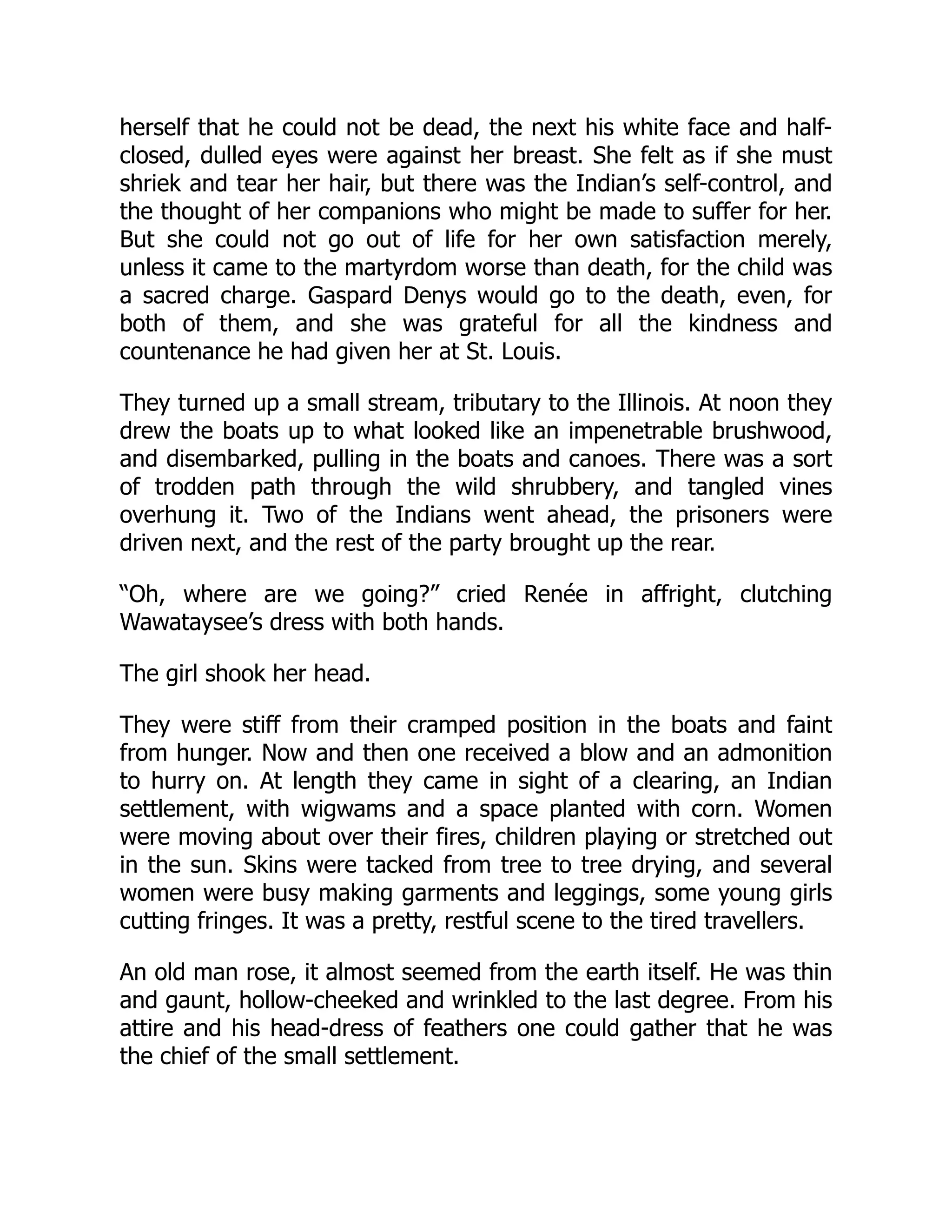

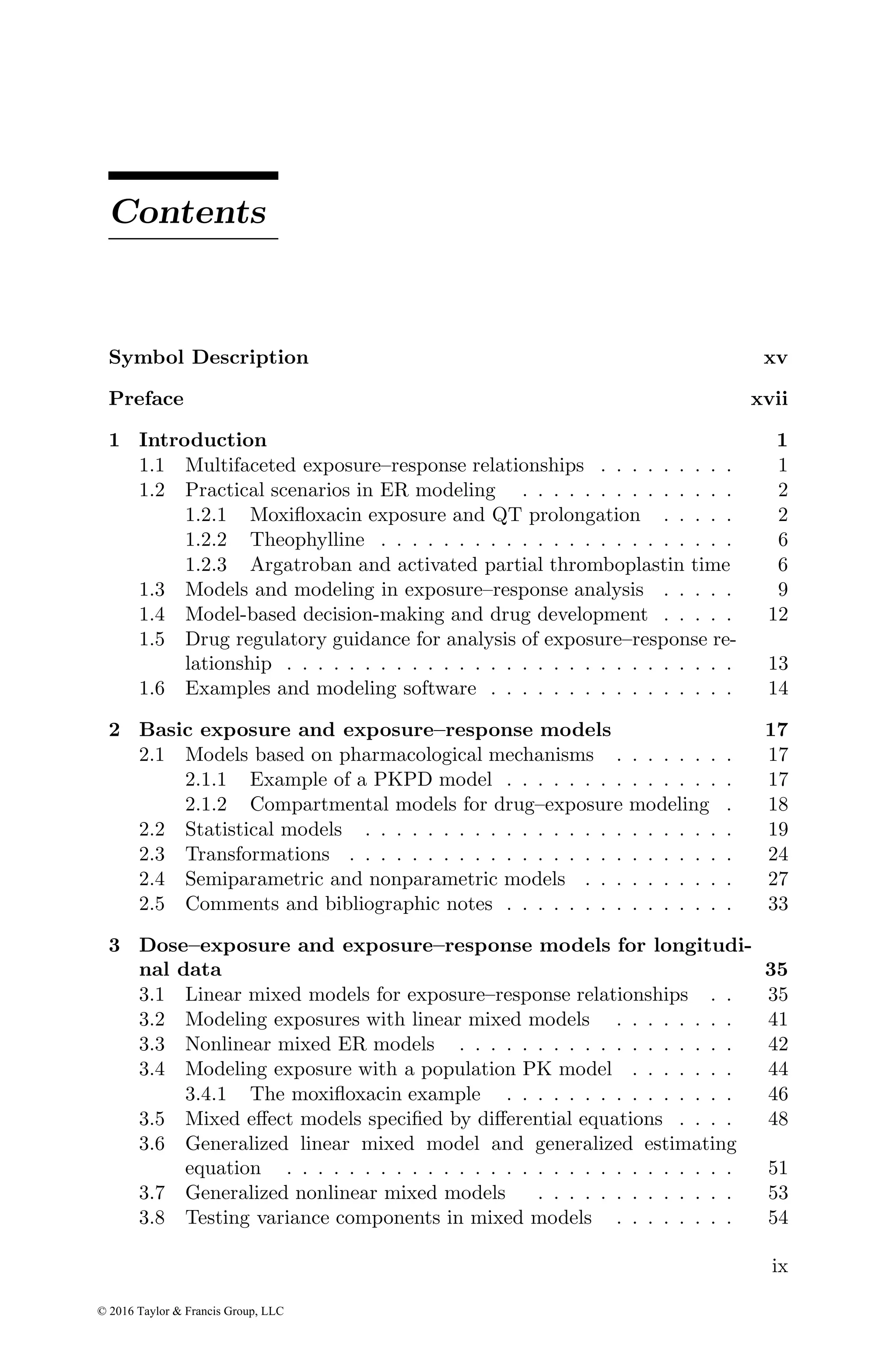

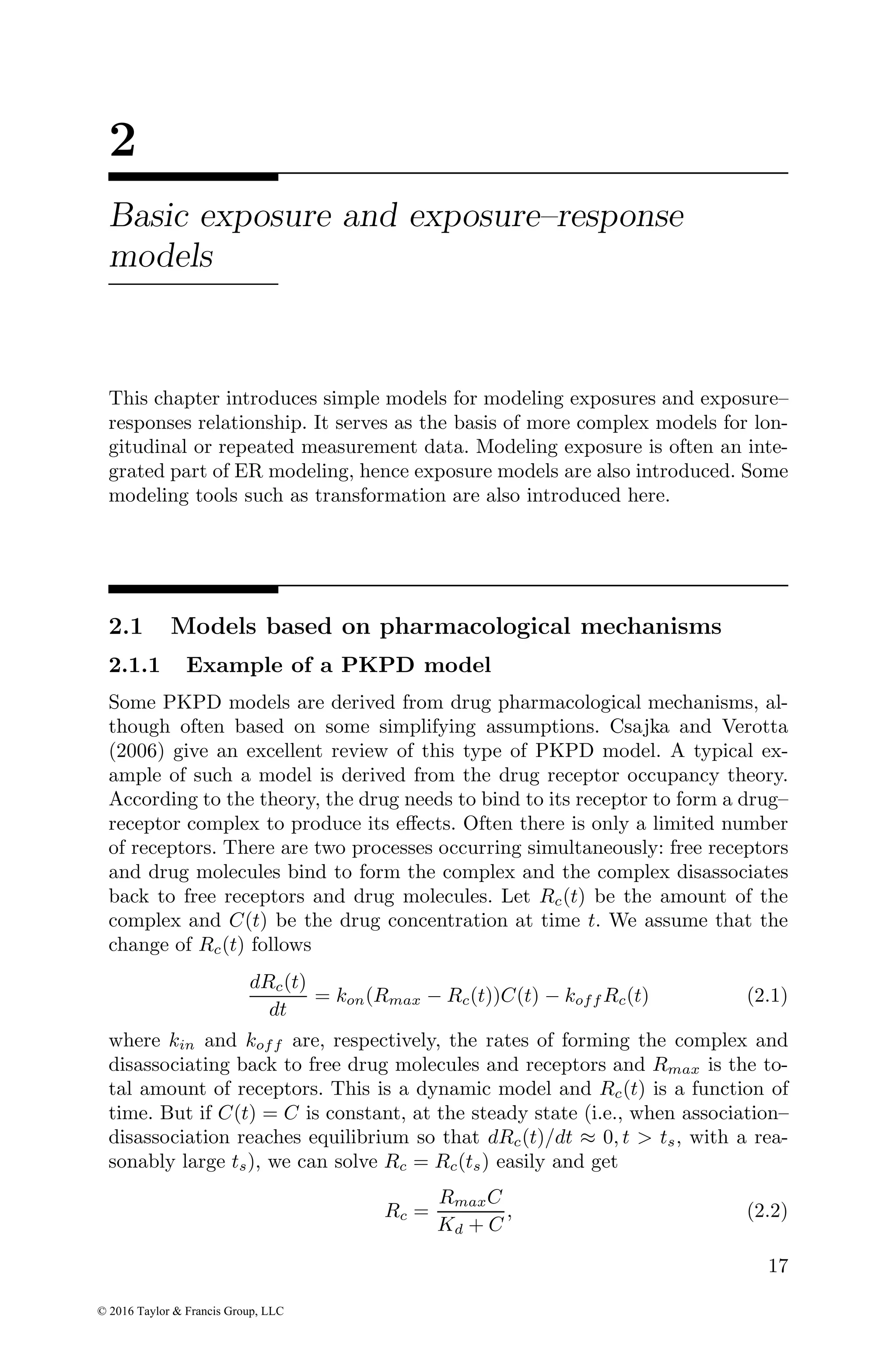

![30 Exposure-Response Modeling: Methods and Practical Implementation

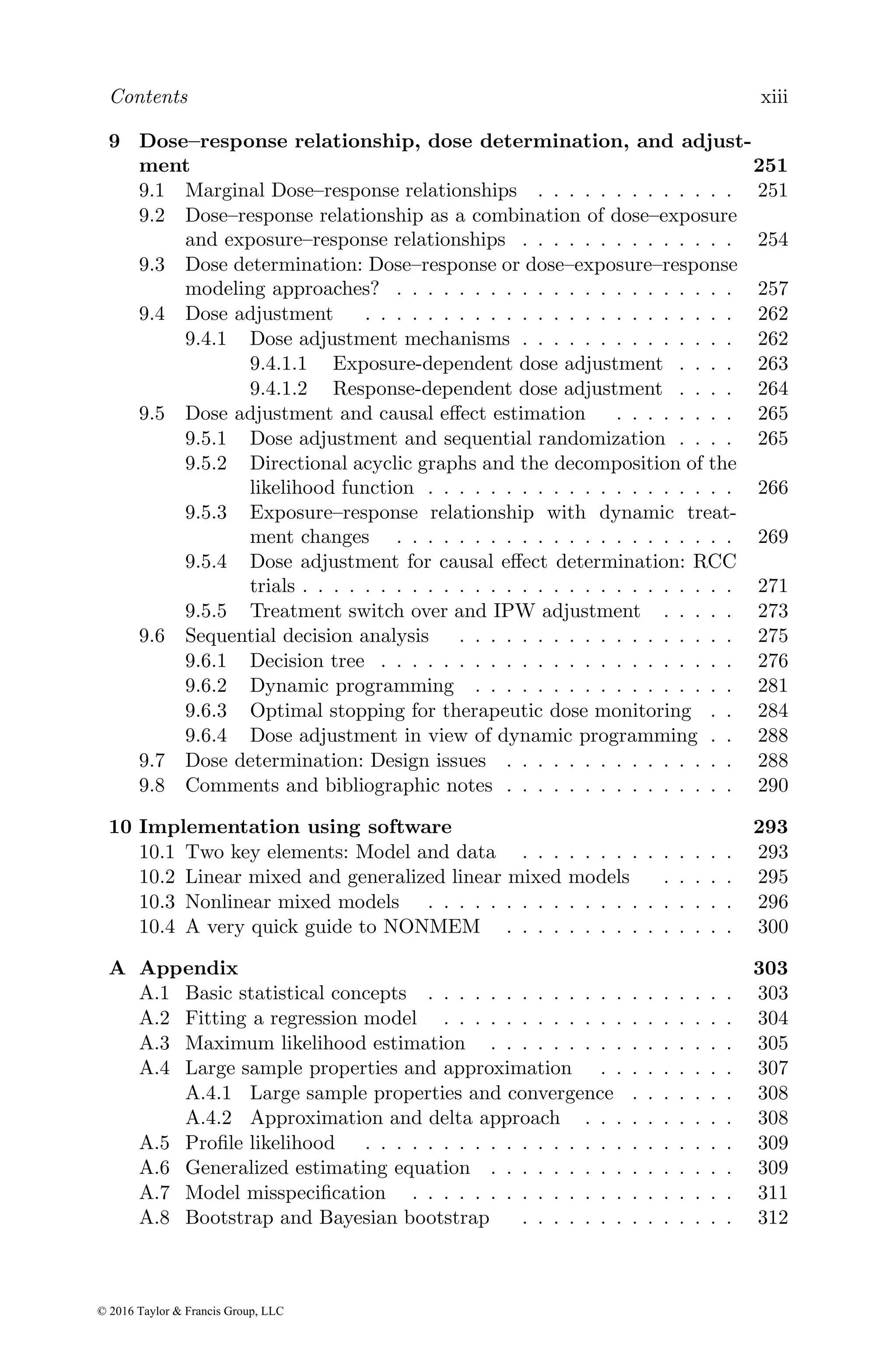

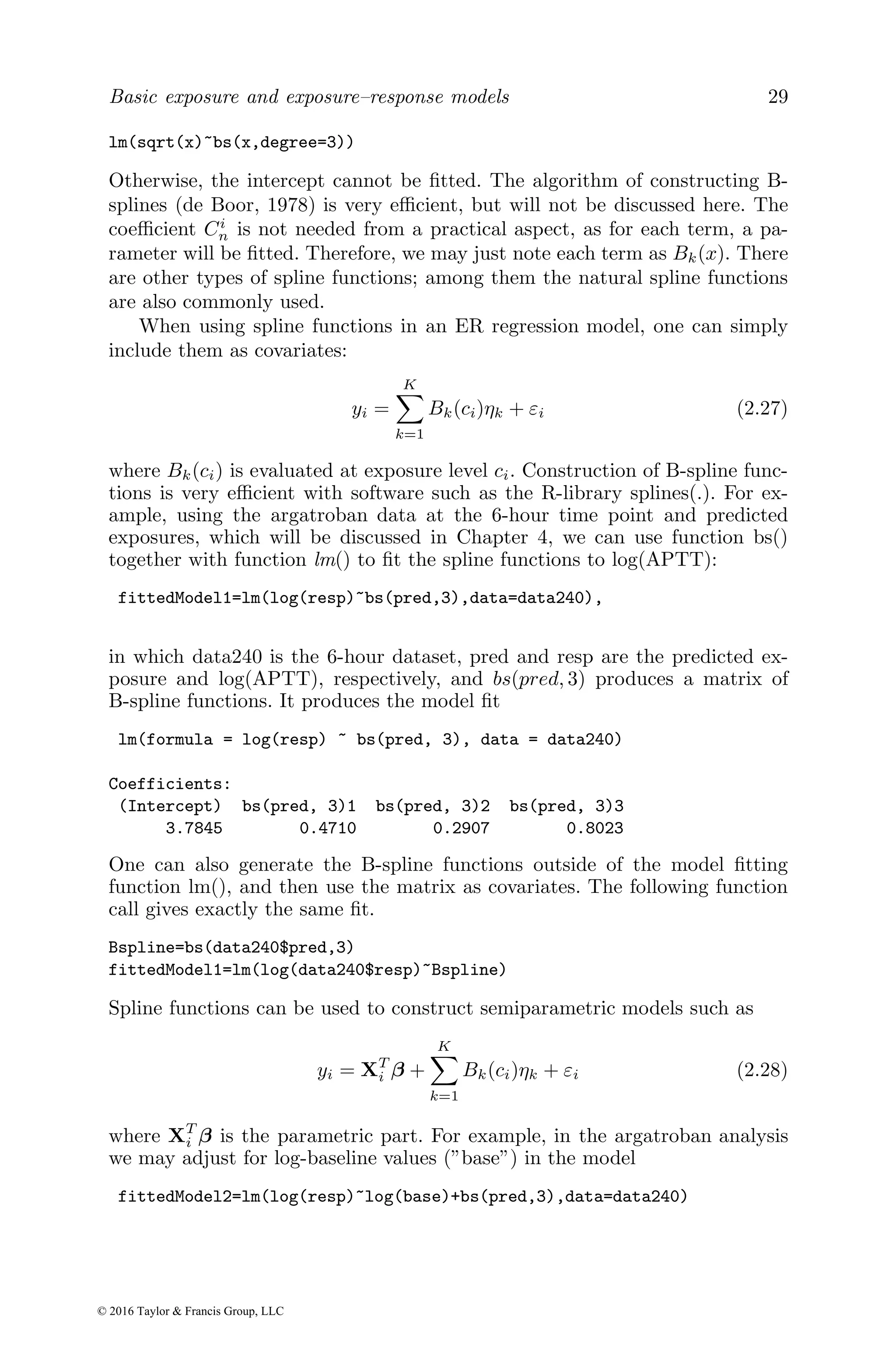

which gives

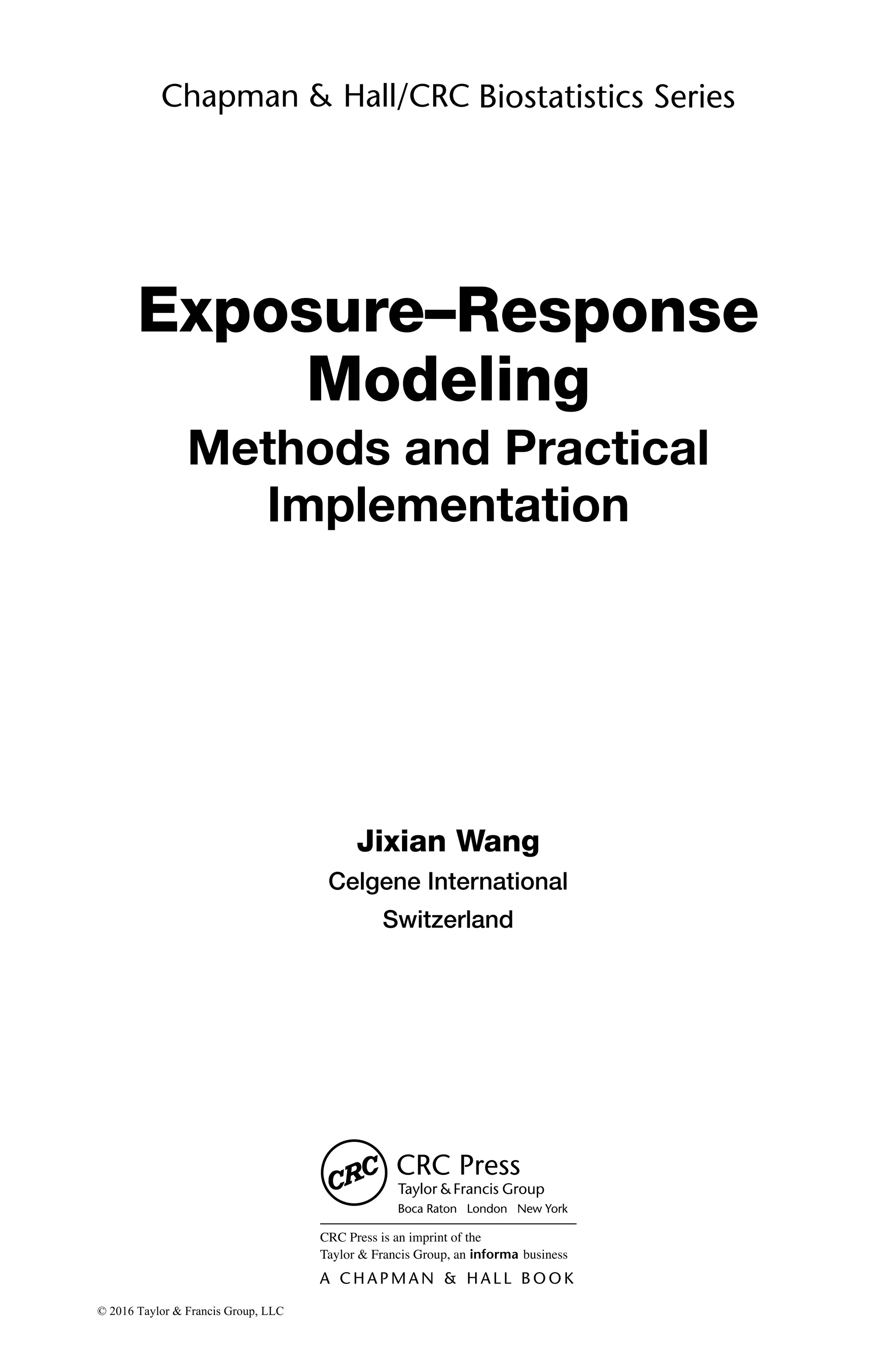

lm(formula = log(resp) ~ log(base) + bs(pred, 3), data = data240)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) log(base) bs(pred, 3)1 bs(pred, 3)2 bs(pred, 3)3

1.2619 0.7671 0.3914 0.3924 0.7522

The coefficients for the spline functions are difficult to interpret directly. But

since the B-spline functions are basis functions between the knots, an increas-

ing trend of the coefficient indicates the same trend in the exposure–response

relationship. This can also be seen from the previous B-spline examples in

(0,1).

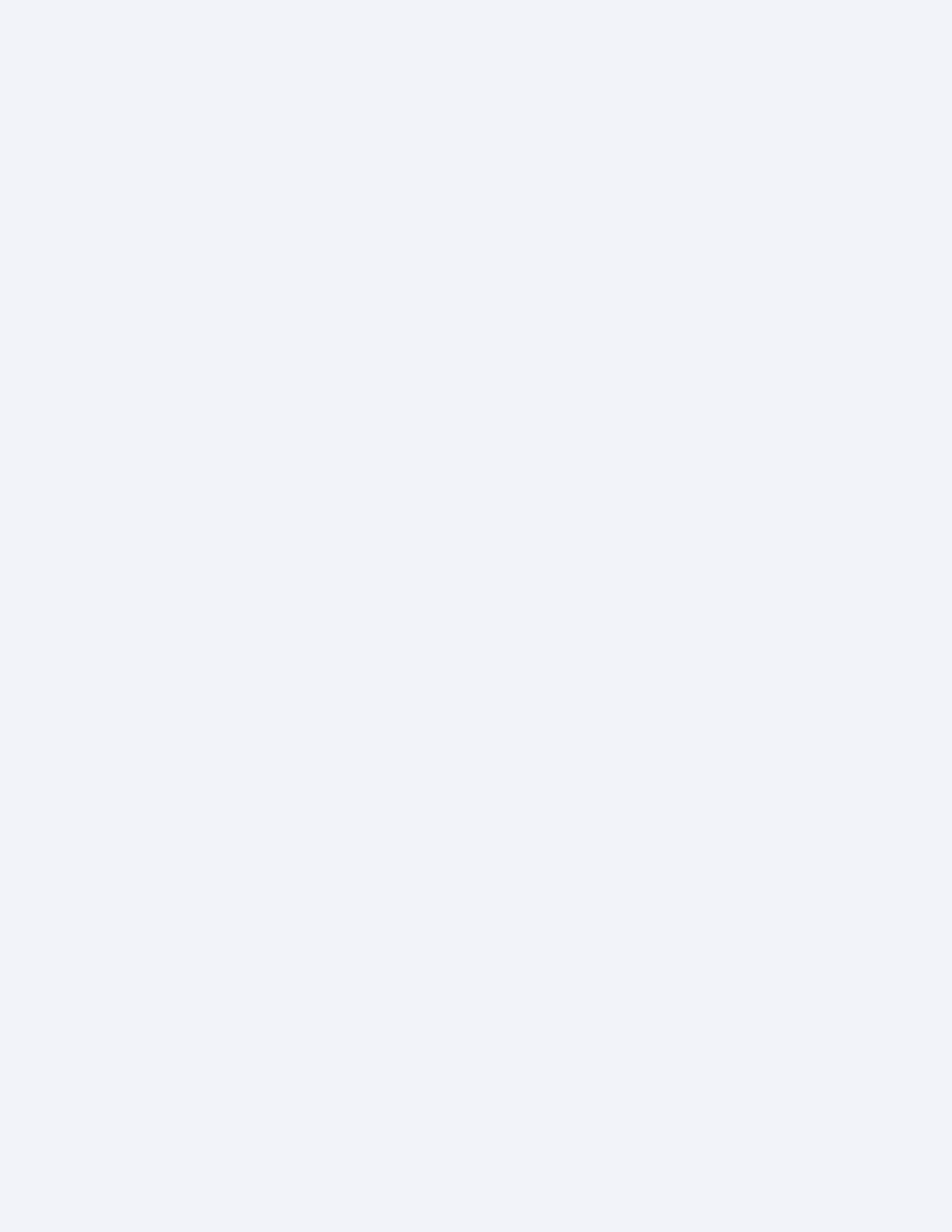

In a semiparametric model, it could be that the nonparametric or the

parametric part is of the primary interest. For example, to explore the dose-

response relationship in argatroban data, one may fit a model with spline

functions for the time profile using dose as the covariate. Since this analysis

involves repeated measurements and needs a linear mixed model, it will be

postponed until the next chapter.

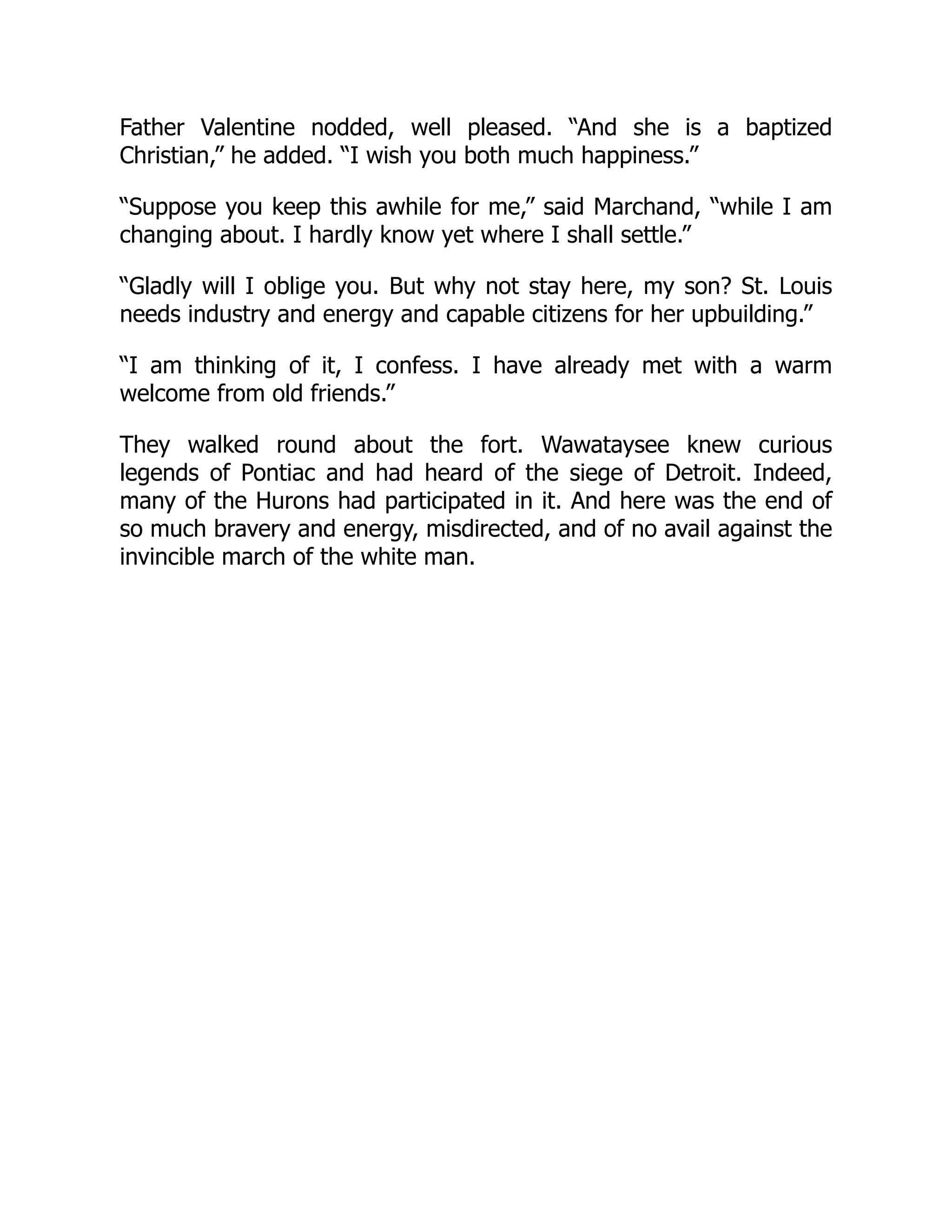

Semiparametric methods can also be used to extend GLMs by using a

smoothing method on the linear predictor. For example, one can add spline

functions for exposure to a GLM model and obtain

g(E(yi)) = XT

i β +

K

X

k=1

Bk(ci)ηk. (2.29)

This type of model is known as a generalized additive model, as the spline

function part is additive in the linear predictor. We have seen a large difference

between the fitted logistic models with and without placebo data, indicating

that the data present a more complex ER relationship than a linear model can

describe. Fitting a logistic model with natural cubic spline functions using

fit=gam(qtp~ns(conc,3),family=binomial,data=moxi[moxi$time==2,])

where qtq and conc are the moxifloxacin concentration and response, respec-

tively, at 2 hours, gives a bell-shaped curve for the relationship between the

concentration and logOR (Figure 2.1). The results indicate a nonlinear rela-

tionship between moxifloxacin exposure and QT prolongation globally. The

model fitted to all the data was driven by the strong impact of the risk in-

crease from zero to low concentration, while that fitted to the moxifloxacin

data was affected by the right end of the curve and resulted in a negative lo-

gOR. The lower and higher ends of the curve are very uncertain, as there was

no event between concentration ranges of zero and 1870 ng/mL and higher

than 3000 ng/mL. Although there is an initial increase in the risk along with

the exposure increase, the left part of the curve cannot be quantified. There

is no evidence of an ER relationship in the higher concentration range. In

summary, there is not sufficient information to quantify the overall ER rela-

tionship based on the parametric and semiparametric models. We will show

© 2016 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2645101-250722182738-ee90be60/75/Exposureresponse-Modeling-Methods-And-Practical-Implementation-1st-Edition-Jixian-Wang-52-2048.jpg)