Exposure Response Modeling Methods and Practical Implementation 1st Edition Jixian Wang

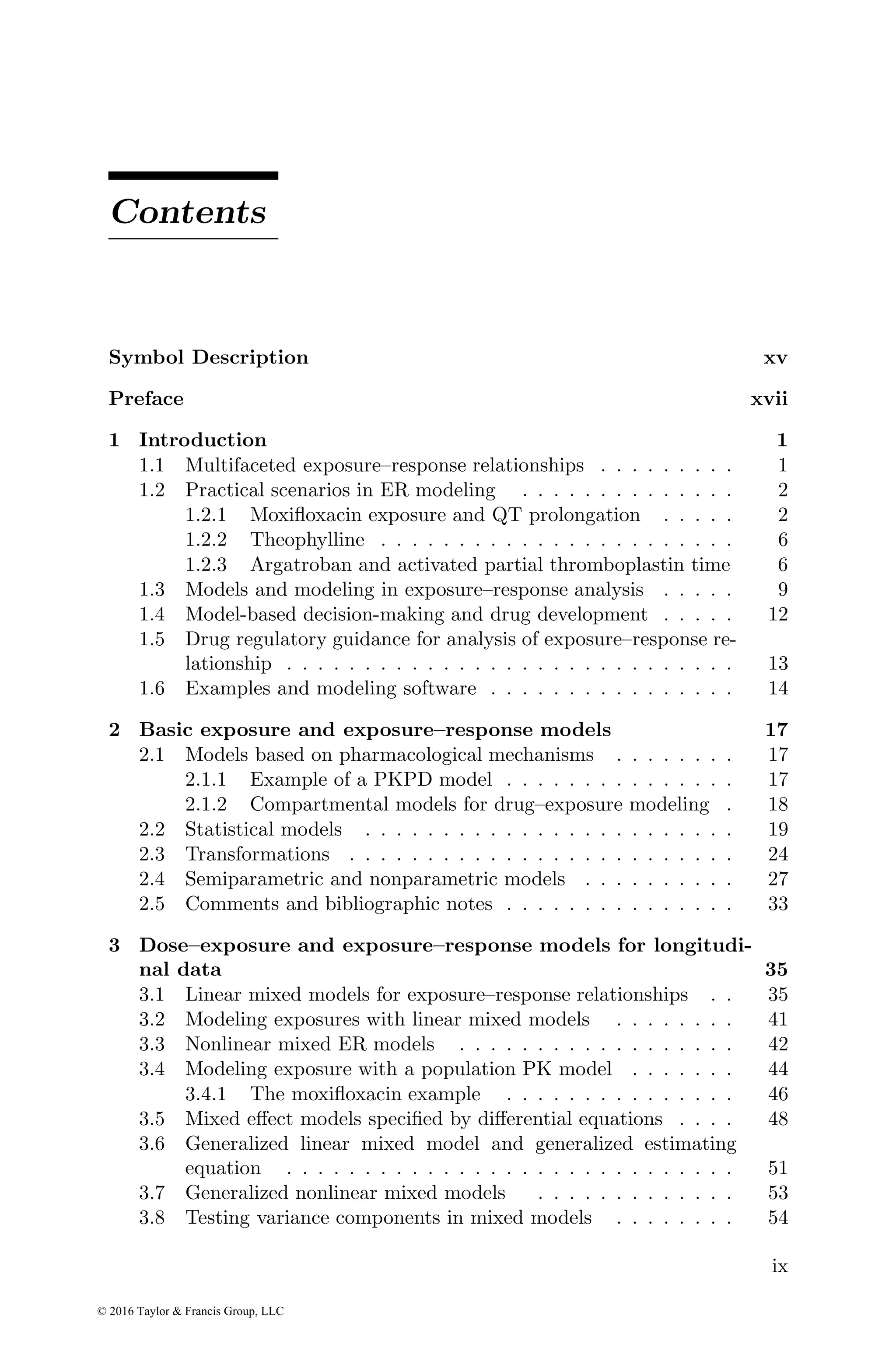

Exposure Response Modeling Methods and Practical Implementation 1st Edition Jixian Wang

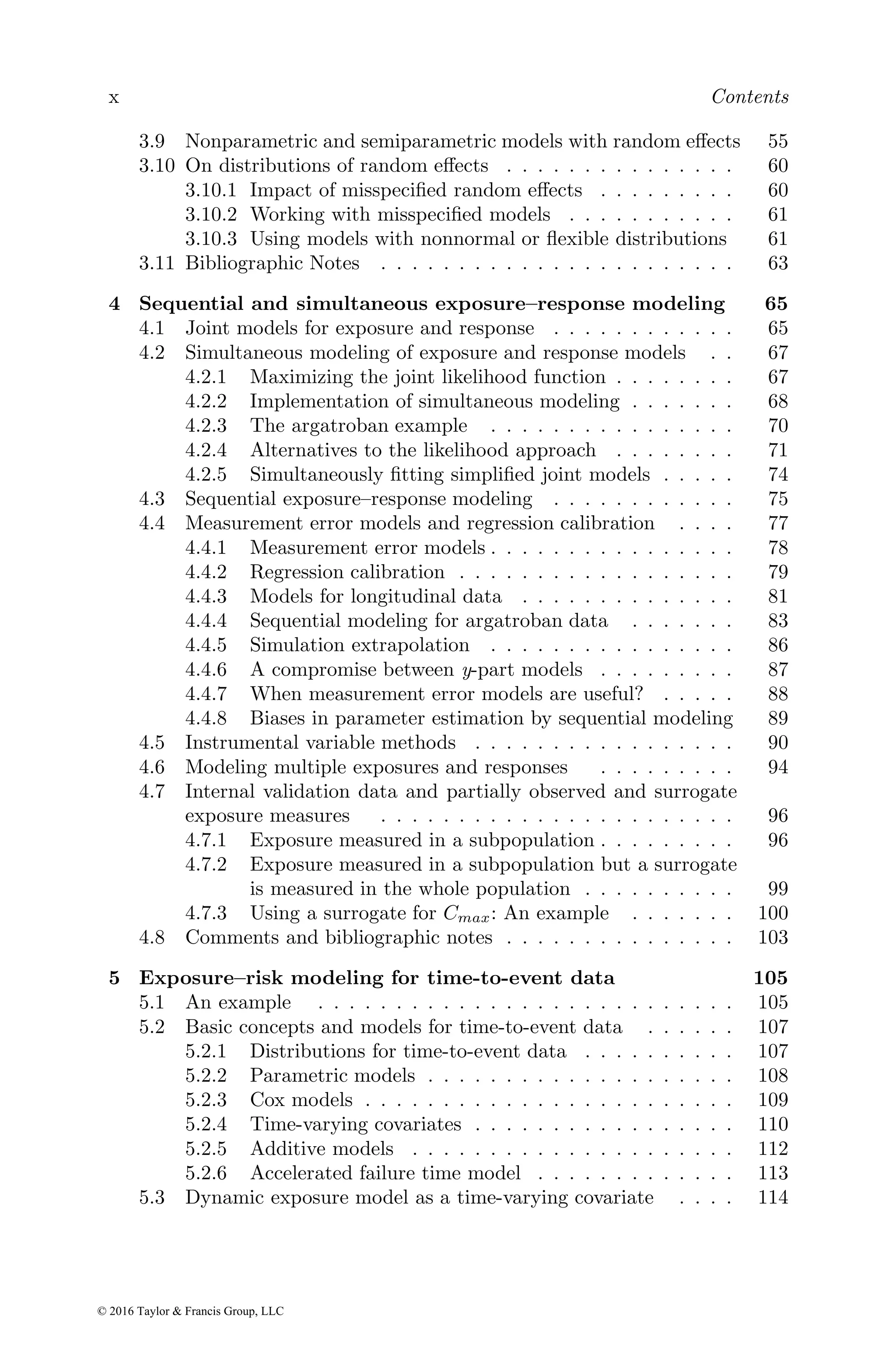

Exposure Response Modeling Methods and Practical Implementation 1st Edition Jixian Wang