The document discusses software metrics, which are quantifiable measures of software characteristics critical for performance evaluation, planning, productivity assessment, and process improvement. It categorizes metrics into product, process, and project metrics, explaining their respective uses, characteristics, and the importance of metrics in software development processes. Additionally, it introduces specific measurement methods such as function points and various factors affecting software metrics, along with guidelines and principles for effective usage.

![MOOD Metrics Set

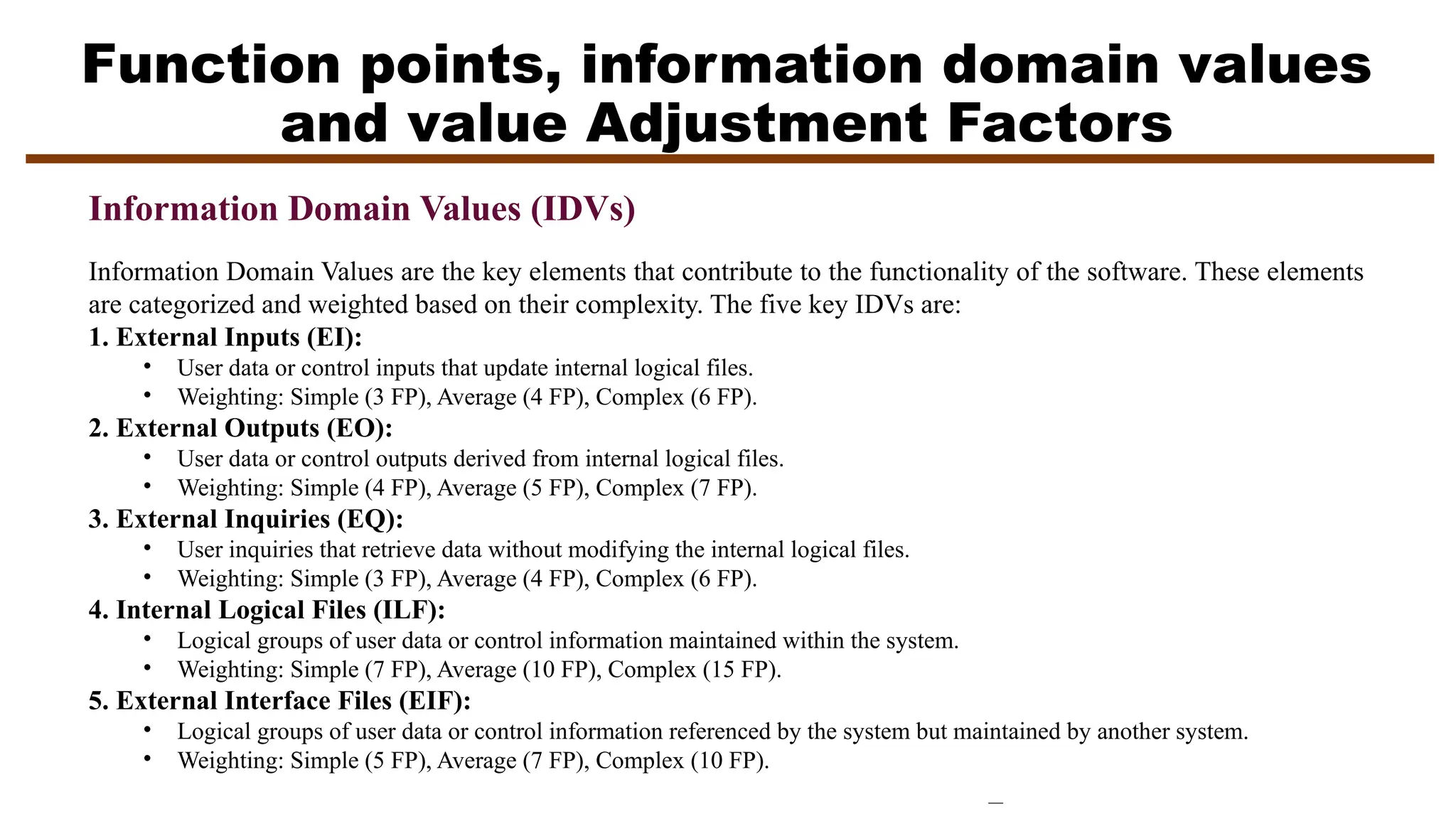

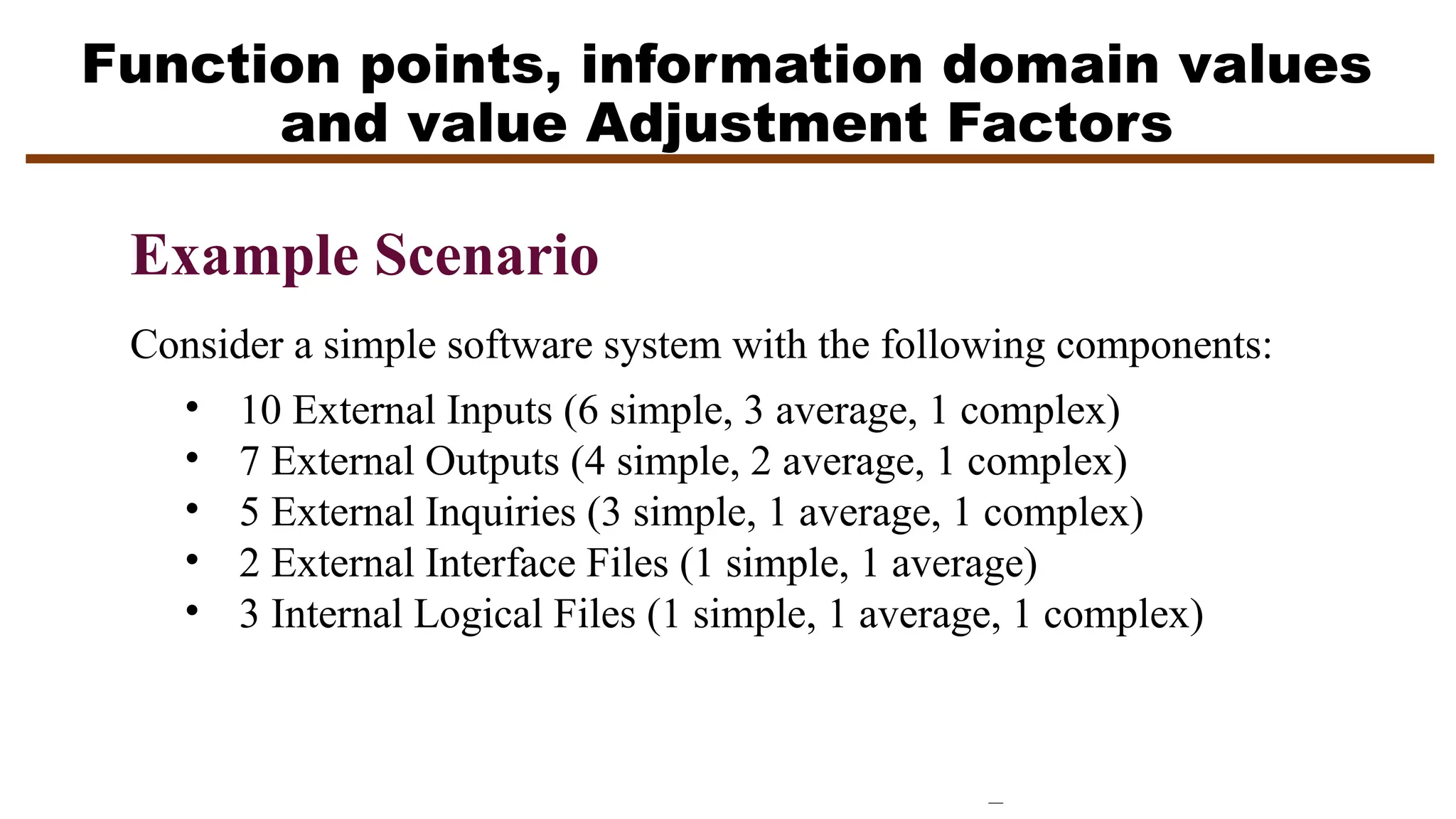

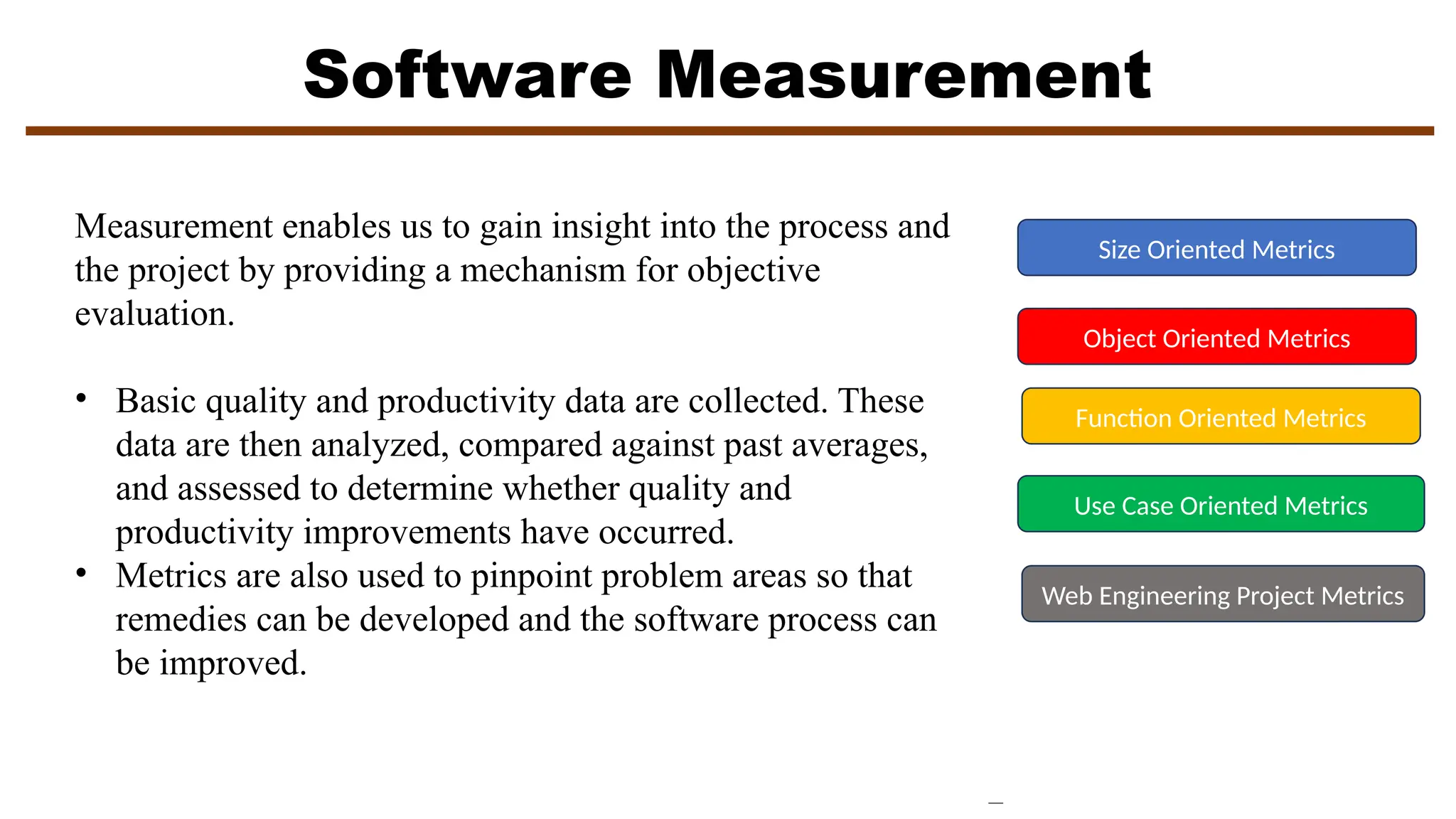

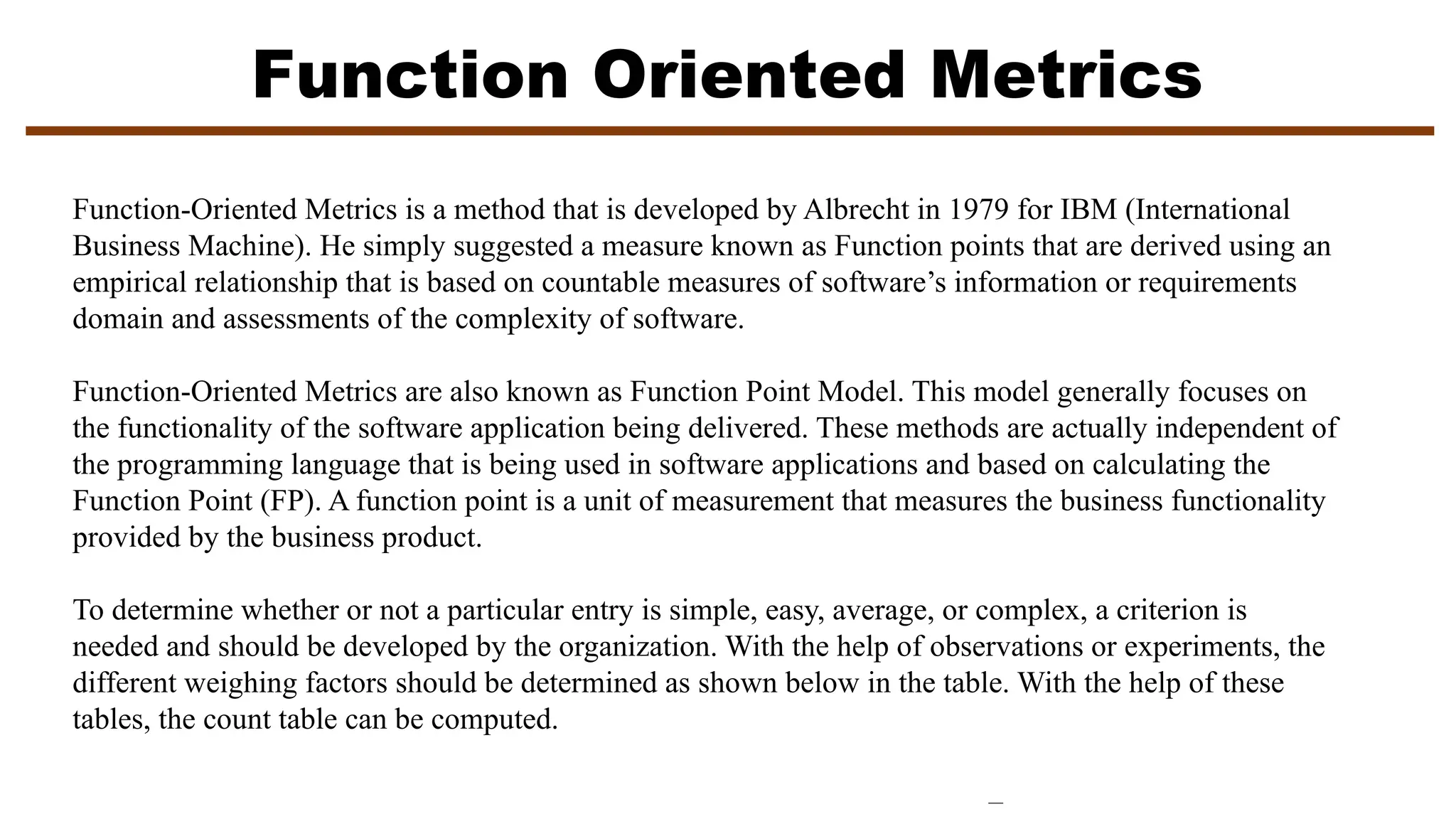

Coupling factor (CF)

Earlier in this chapter we noted that coupling is an indication of the connections between elements of

the OO design. The MOOD metrics suite defines coupling in the following way:

CF = Σi Σj is_client (Ci, Cj)]/(TC2 -TC)

where the summations occur over i = 1 to TC and j = 1 to TC. The function is_client = 1, if and only if

a relationship exists between the client class, Cc, and the server class, Cs, and Cc ≠ Cs

= 0, otherwise

Although many factors affect software complexity, understandability, and maintainability, it is

reasonable to conclude that, as the value for CF increases, the complexity of the OO software will also

increase and understandability, maintainability, and the potential for reuse may suffer as a result.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/metrics-241130134049-6f7a5886/75/Comprehensive-Analysis-of-Metrics-in-Software-Engineering-for-Enhanced-Project-Management-and-Quality-Assessment-30-2048.jpg)

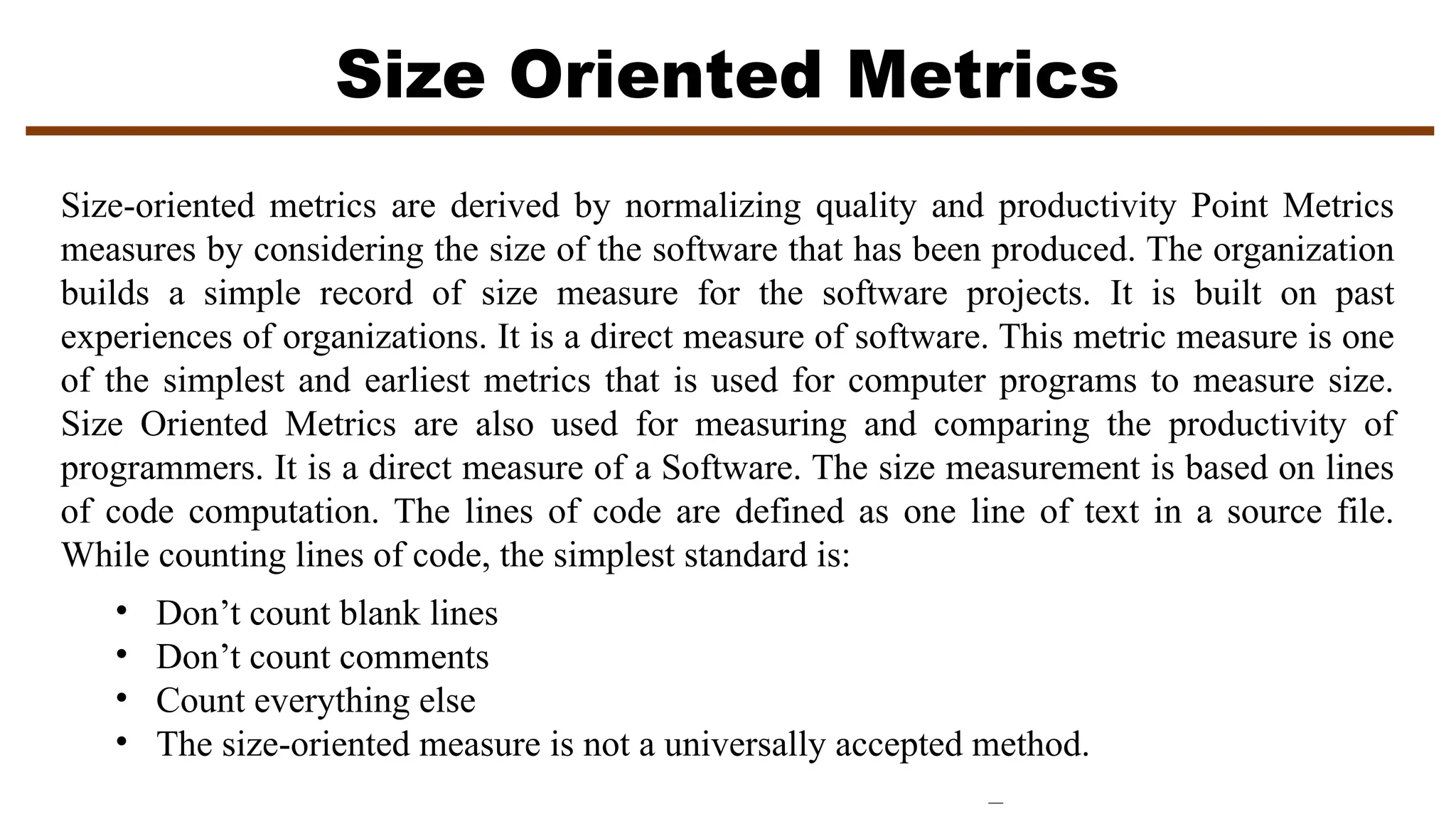

![Metrics For Testing

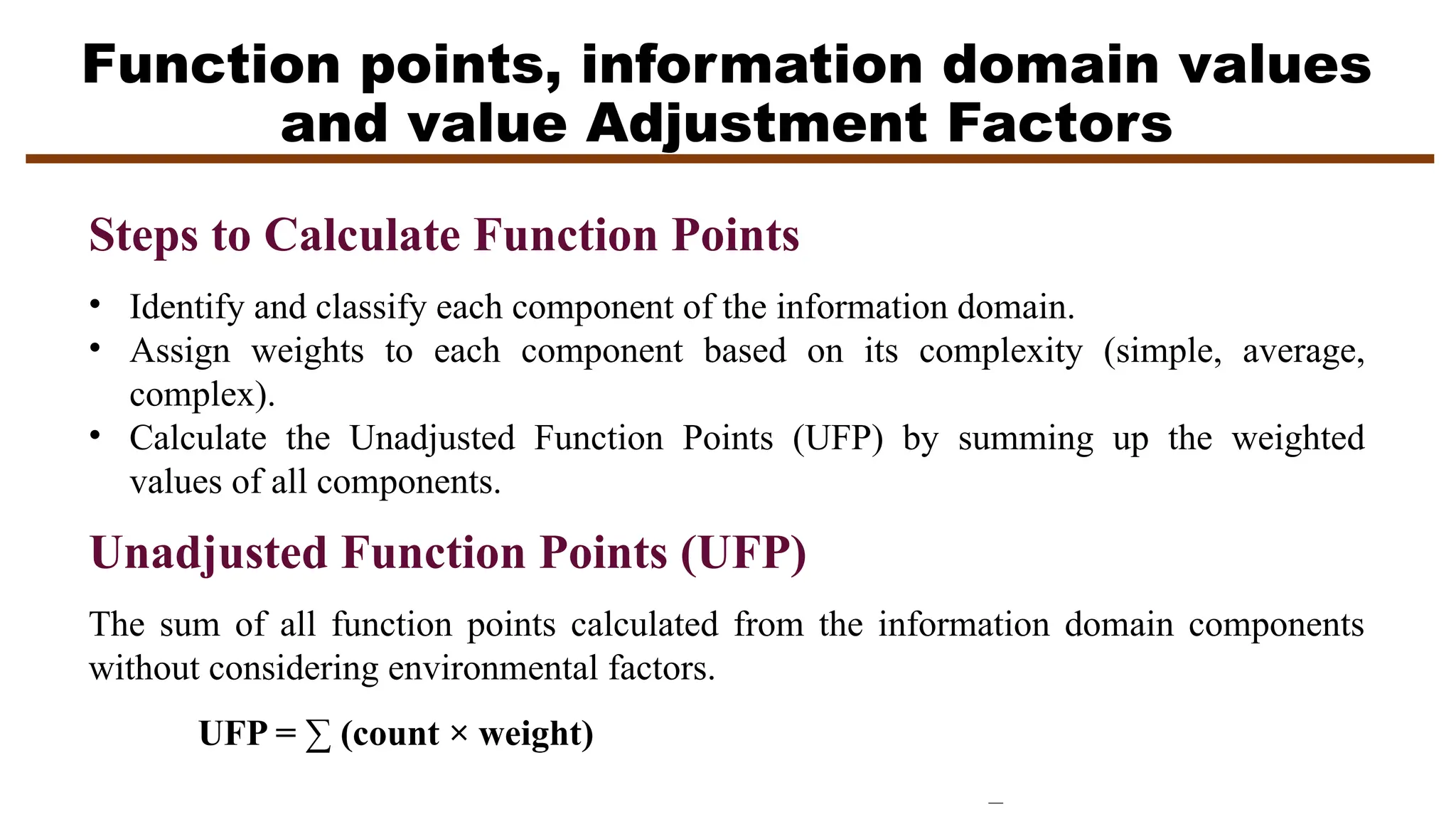

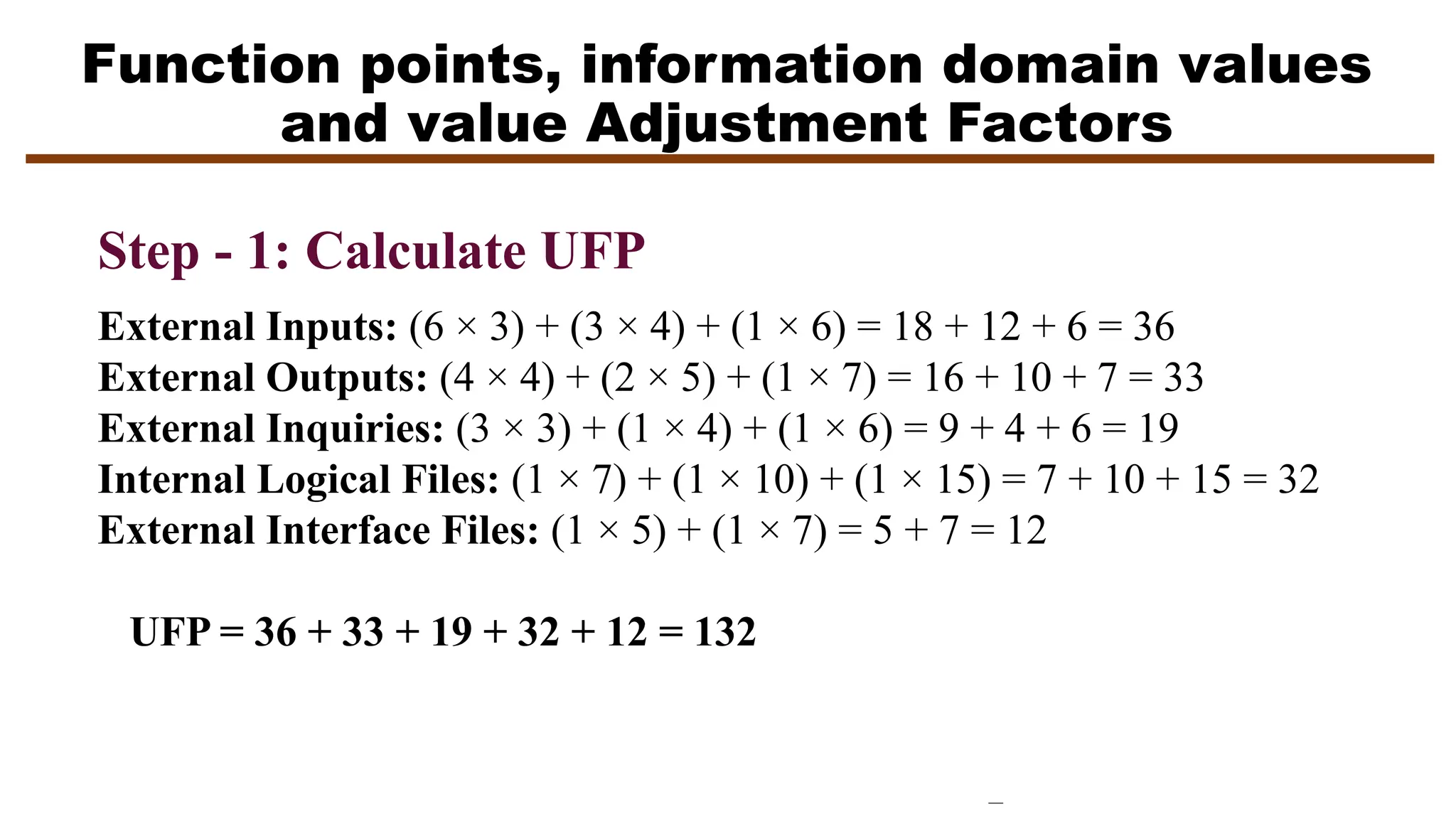

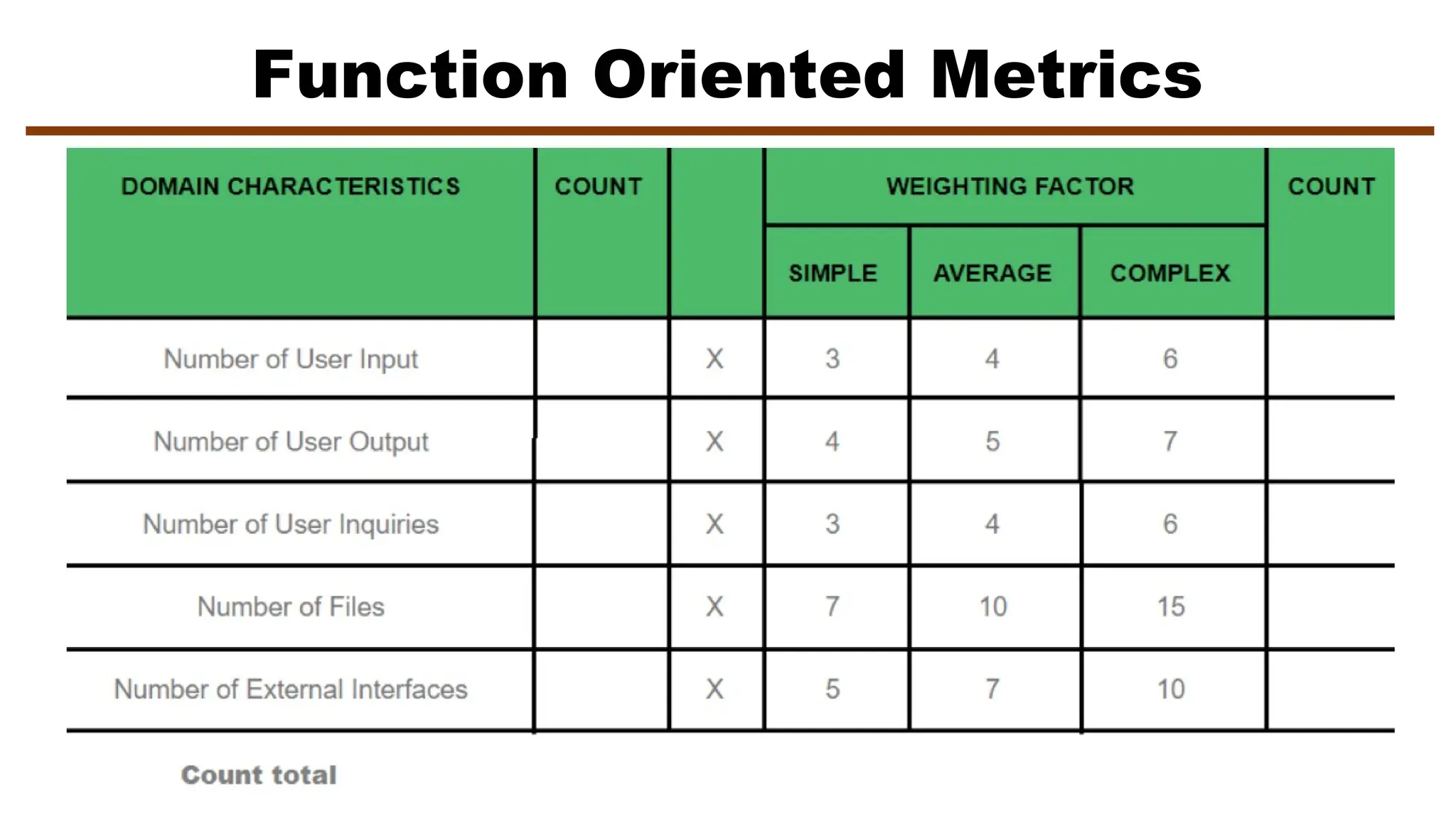

Testing effort can also be estimated using metrics derived from Halstead measures. Using the

definitions for program volume, V, and program level, PL, software science effort, e, can be computed

as

PL = 1/[(n1/2)•(N2/n2)] (1)

e = V/PL (2)

The percentage of overall testing effort to be allocated to a module k can be estimated using the

following relationship:

percentage of testing effort (k) = e(k)/ e(i) (3)

where e(k) is computed for module k using Equations (1) and (2) and the summation in the denominator

of Equation (4) is the sum of software science effort across all modules of the system.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/metrics-241130134049-6f7a5886/75/Comprehensive-Analysis-of-Metrics-in-Software-Engineering-for-Enhanced-Project-Management-and-Quality-Assessment-32-2048.jpg)

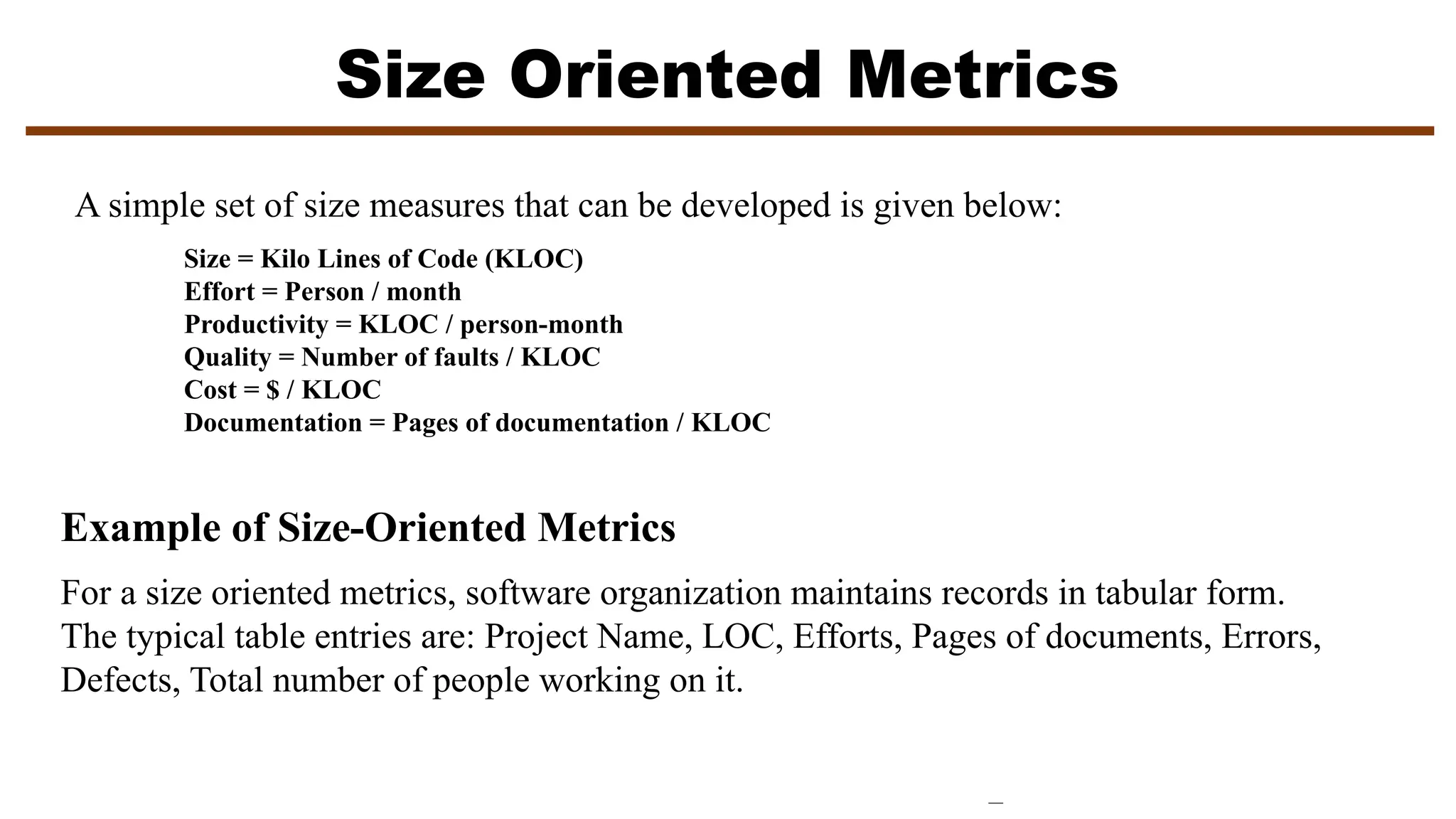

![Metrics For Maintenance

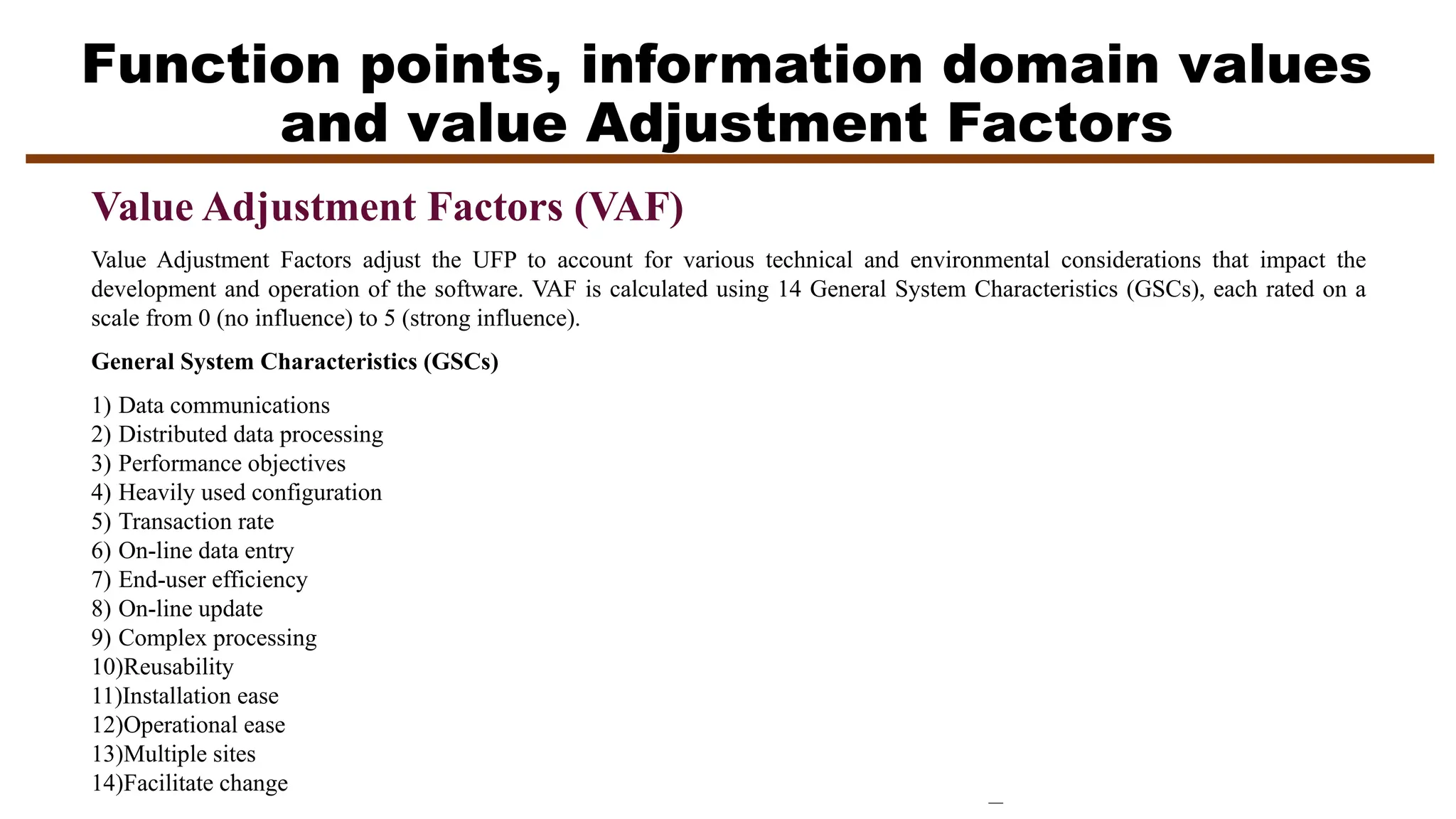

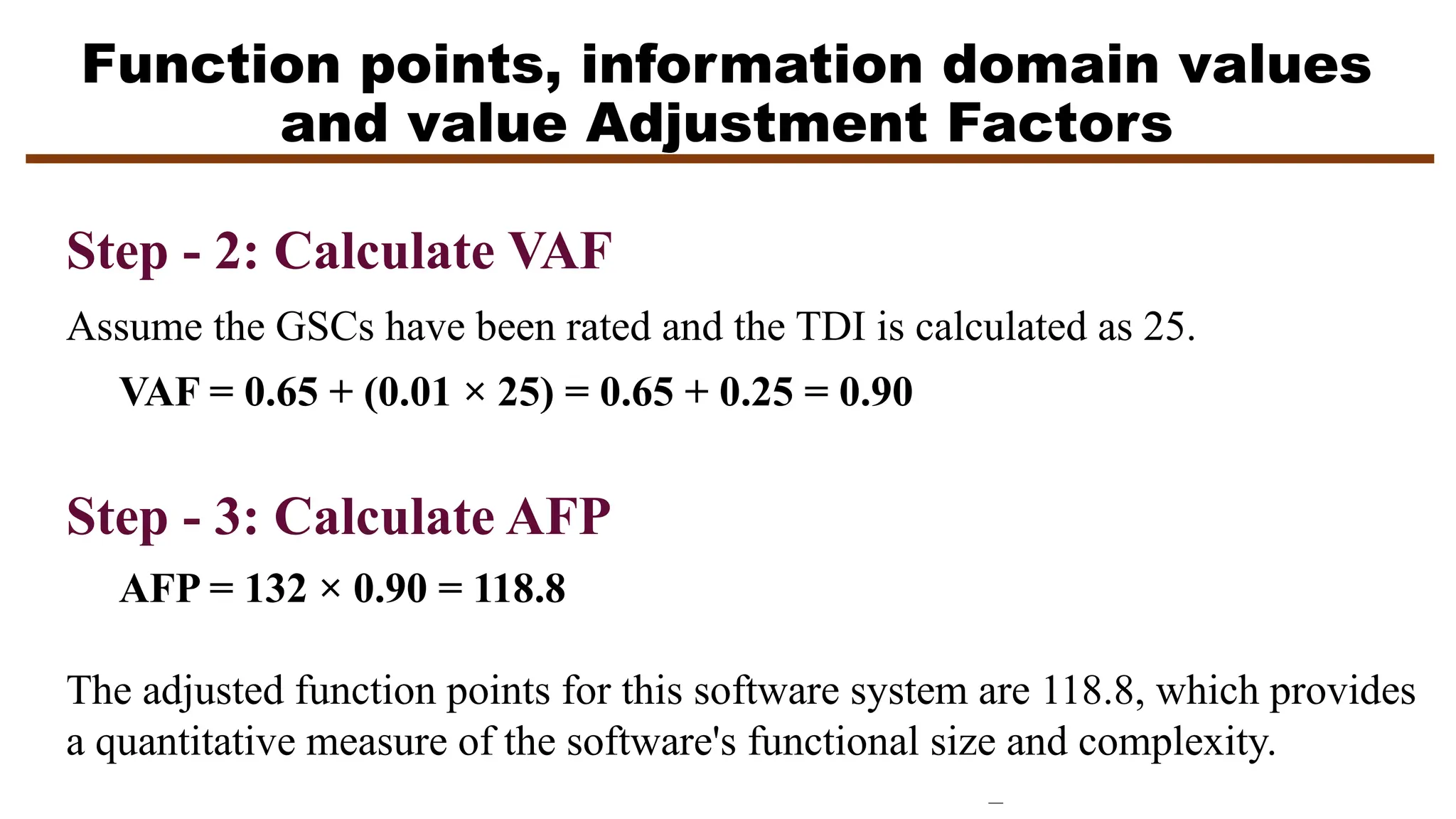

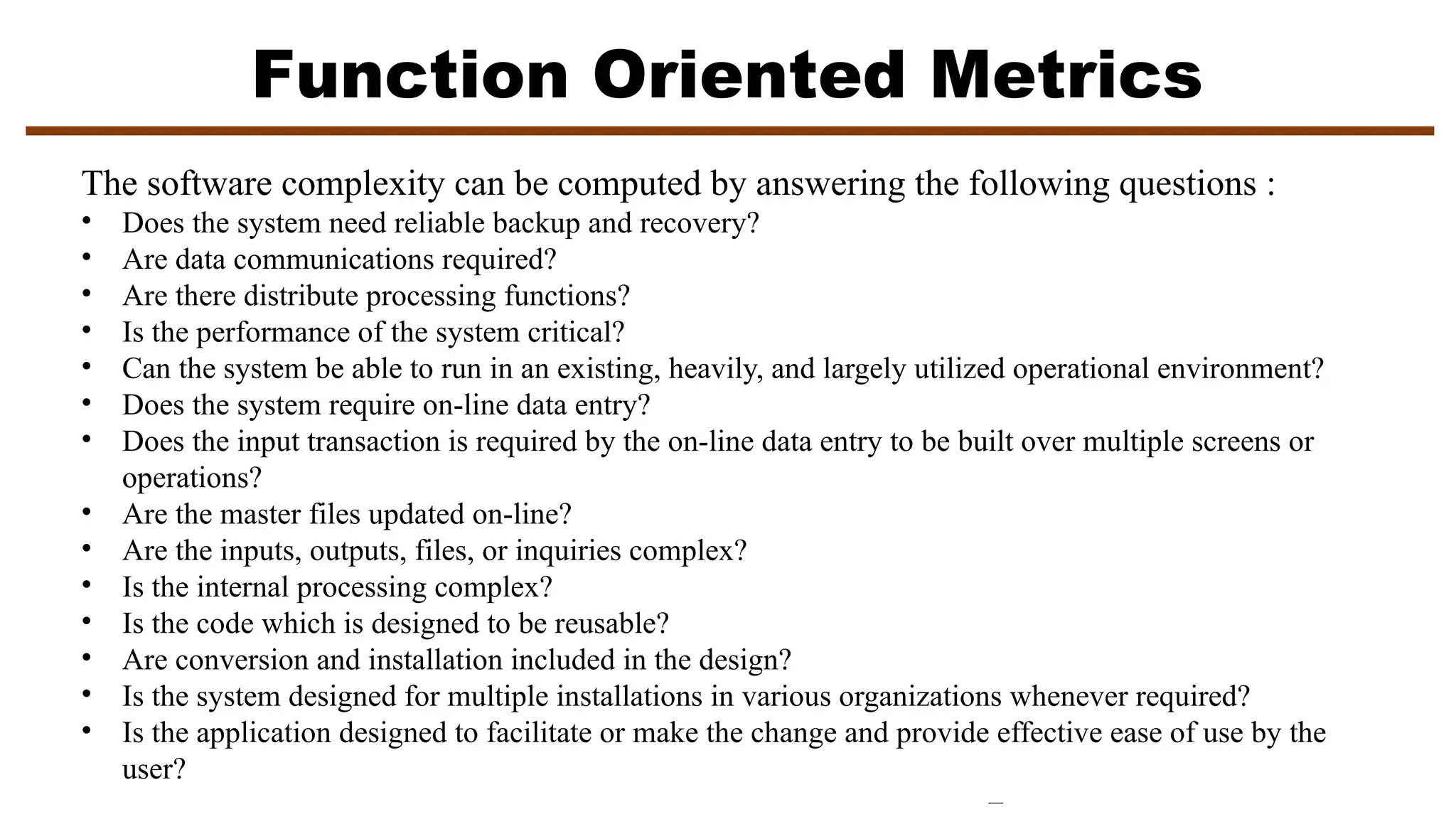

IEEE Std. 982.1-1988 suggests a software maturity index (SMI) that provides an indication of the

stability of a software product (based on changes that occur for each release of the product). The

following information is determined:

MT = the number of modules in the current release

Fc = the number of modules in the current release that have been changed

Fa = the number of modules in the current release that have been added

Fd = the number of modules from the preceding release that were deleted in the current release

The software maturity index is computed in the following manner:

SMI = [MT (Fa + Fc + Fd)]/MT

As SMI approaches 1.0, the product begins to stabilize. SMI may also be used as metric for planning

software maintenance activities. The mean time to produce a release of a software product can be

correlated with SMI and empirical models for maintenance effort can be developed](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/metrics-241130134049-6f7a5886/75/Comprehensive-Analysis-of-Metrics-in-Software-Engineering-for-Enhanced-Project-Management-and-Quality-Assessment-35-2048.jpg)

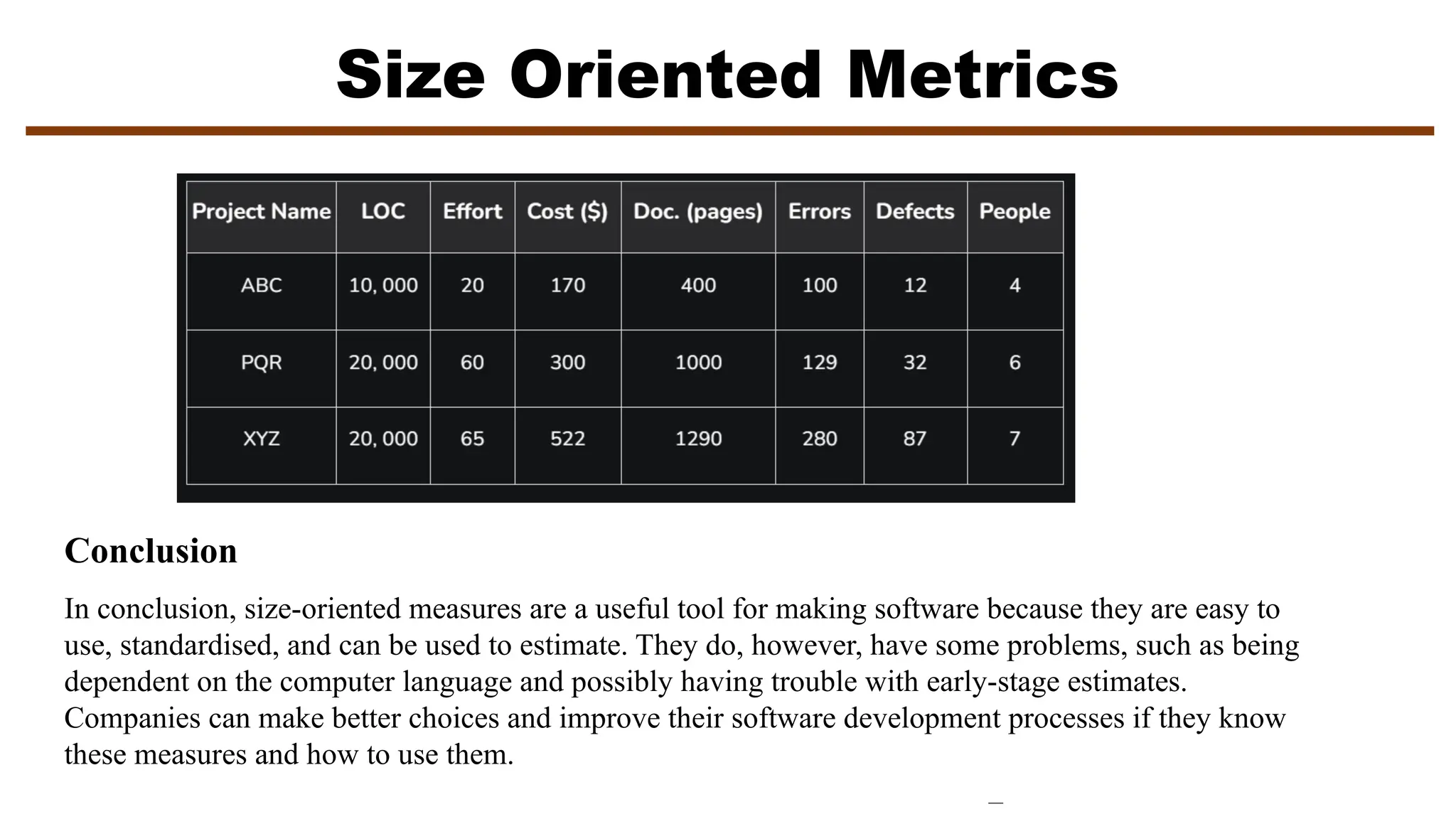

![Measuring Quality

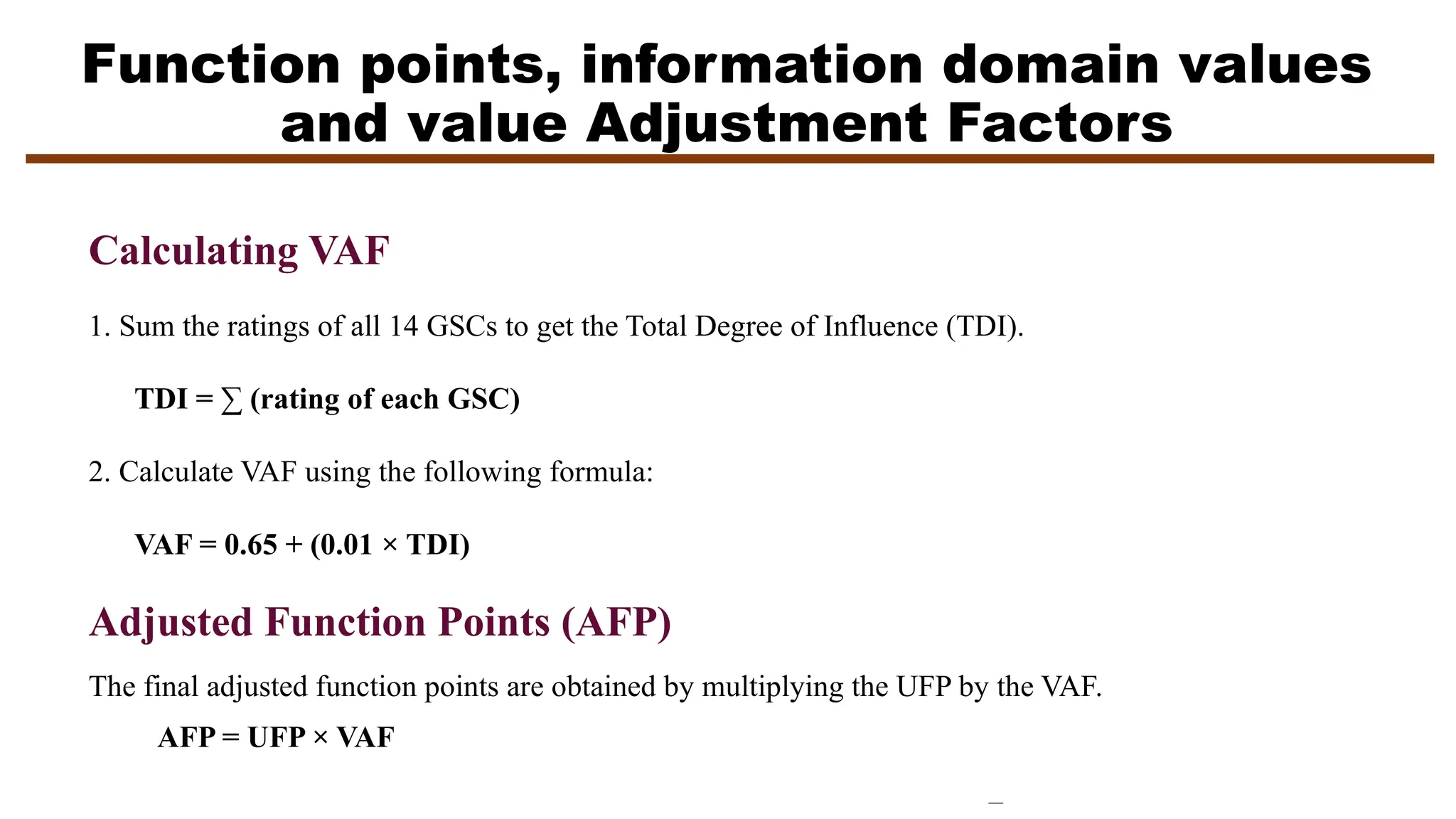

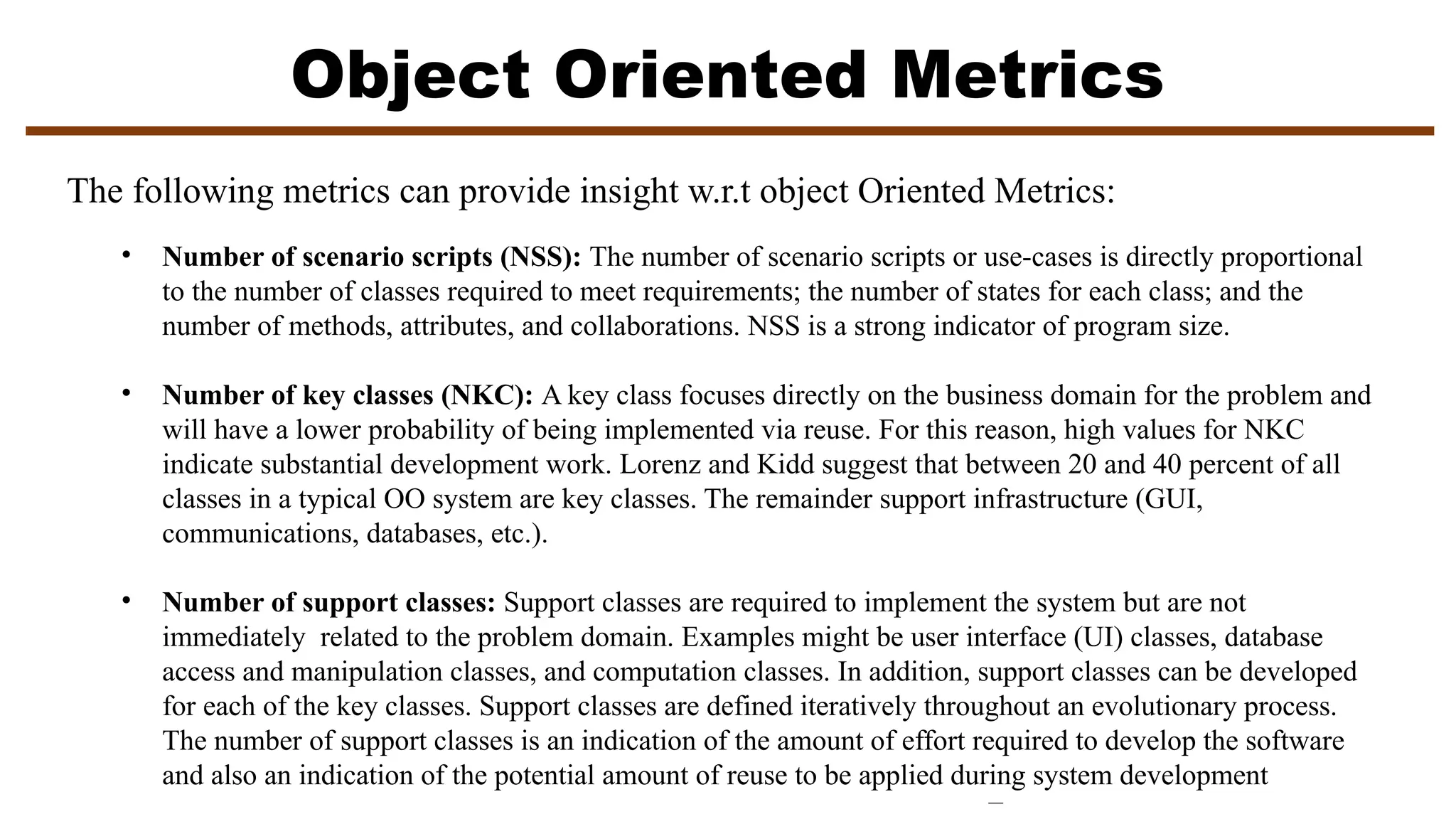

Correctness: defects per KLOC

Maintainability: the ease that a program can be corrected, adapted, and enhanced. Time/cost.

• Time-oriented metrics: Mean-time-to-change (MTTC)

• Cost-oriented metrics: Spoilage – cost to correct defects encountered

Integrity: ability to withstand attacks

• Threat: the probability that an attack of a specific type will occur within a given time.

• Security: the probability that the attack of a specific type will be repelled.

Integrity = sum [(1 – threat)x(1 – security)]

Usability: attempt to quantify “user-friendliness” in terms of four characteristics:

1) The physical/intellectual skill to learn the system

2) The time required to become moderately efficient in the use of the system

3) The net increase of productivity

4) A subjective assessment of user attitude toward the system(e.g., use of questionnaire).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/metrics-241130134049-6f7a5886/75/Comprehensive-Analysis-of-Metrics-in-Software-Engineering-for-Enhanced-Project-Management-and-Quality-Assessment-50-2048.jpg)

![Defect Removal Efficiency

Defect Removal Efficiency (DRE) is the litmus test of your software testing prowess, encapsulating the

effectiveness of your defect identification and resolution endeavors. Think of DRE as a magnifying glass that

zooms in on the accuracy and thoroughness of your testing process.

The Defect Removal Efficiency (DRE) formula acts as a compass in determining and quantifying the quality of

your software product.

The formula for computing the defect removal efficiency is:

DRE (%) = [Total Defects Found in Testing / (Total Defects Found in Testing + Total Defects Found in Production)] x 100

Where:

Total Defects Found in Testing: The number of defects discovered during the testing phase of software

development.

Total Defects Found in Production: The number of defects reported by users or detected after the software

has been released to the production environment.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/metrics-241130134049-6f7a5886/75/Comprehensive-Analysis-of-Metrics-in-Software-Engineering-for-Enhanced-Project-Management-and-Quality-Assessment-51-2048.jpg)