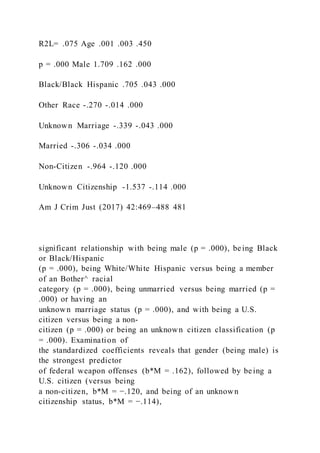

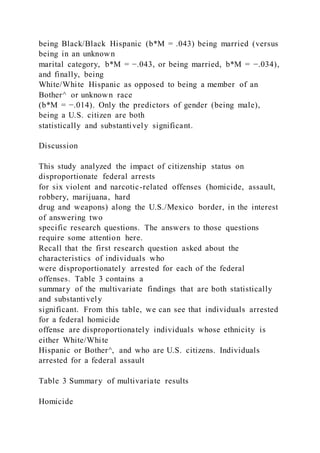

This research examines the relationship between citizenship status and arrest patterns for violent and narcotic-related offenses along the U.S./Mexico border, showing that U.S. citizens are disproportionately arrested for violent crimes while non-citizens are more likely to be arrested for marijuana offenses. The findings challenge the common stereotype of immigrants being more prone to criminal behavior, suggesting that empirical evidence does not support the notion that illegal immigrants contribute to higher crime rates. Overall, the study provides a critical analysis of media narratives and public perceptions regarding immigration and crime in border communities.

![The myth of the criminal immigrant is perhaps one of the single

most controversial

factors contributing to America’s present day anti-immigrant

fervor. In their book, The

Am J Crim Just (2017) 42:469–488

DOI 10.1007/s12103-016-9375-1

* Wendi Pollock

[email protected]

Deborah Sibila

[email protected]

Scott Menard

[email protected]

1 Department of Government, Stephen F. Austin State

University, Box 13045 SFA Station,

Nacogdoches, TX 75962, USA

2 Department of Social Sciences, Texas A&M University, 6300

Ocean Drive, Corpus Christi,

TX 78412, USA

3 Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado,

Boulder, USA

http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1007/s12103-016-

9375-1&domain=pdf

Immigration Time Bomb, authors Richard D. Lamm and Gary

Imhoff contend that the

issue of immigration and crime is a critically divisive topic

easily subject to misinter-

pretation (1985, p. 21). The belief that immigrants are more

crime-prone than native-

born is not a twentieth century development. Debates on this](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/citizenshipstatusandarrestpatternsforviolentandnarcot-220921161002-4e0bb558/85/Citizenship-Status-and-Arrest-Patterns-for-Violentand-Narcot-2-320.jpg)

![controversy date back

more than 100 years (Hagan & Palloni, 1998; Martinez & Lee,

2000). Hagan and

Pallon believed that the nexus between immigration and crime

is so misleading that it

constitutes a mythology (1999, p. 630). In a special report for

the Immigration Policy

Center, professors Ruben Rumbaut and Walter Ewing wrote

B[The] misperception that

the foreign-born, especially illegal, immigrants are responsible

for higher crime rates is

deeply rooted in American public opinion and sustained by

media anecdote and

popular myth^ (2007, p. 3). Lee (2013) similarly argues that

immigrants have a long

history of serving as scapegoats for a vast array of America’s

societal problems

including crime.

Public opinion surveys suggest that a significant number of

Americans believe that

immigrants, particularly illegal immigrants, are associated with

higher crime rates

(Kohut et al., 2006; Muste, 2013; Sohoni & Sohoni, 2014).

Media sources routinely

associate immigration, especially Hispanic immigrants, with

crime (Bender, 2003;

Martinez, 2002). Politicians also play a key role in perpetuating

the belief that

immigrants and crime are interrelated. Arizona Governor Jan.

Brewer, Senator John

McCain and former presidential hopeful Patrick Buchanan are

just a few political

figures that have gone on record linking immigration directly

with high crime rates

(Butcher & Piehl, 1998; USA Today, 2011). On May 15, 2006,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/citizenshipstatusandarrestpatternsforviolentandnarcot-220921161002-4e0bb558/85/Citizenship-Status-and-Arrest-Patterns-for-Violentand-Narcot-3-320.jpg)

![immigration and crime were

limited and were focused at the individual level (Abbott, 1915;

Hourwich, 1912; Lind,

1930; Taft, 1933, 1936; Van Vechten, 1941). These studies

found little evidence of a

causal relationship between immigration and crime. Three major

government commis-

sions (the Industrial Commission of 1901, the [Dillingham]

Immigration Commission

of 1911, and the [Wickersham] National Commission on Law

Observance and

Enforcement of 1931) similarly explored the issue of whether

immigration increases

crime. Each of the commissions found that immigrants were less

likely to commit

crime than were their native-born counterparts.

More recent studies investigating the association between

immigration and crime

tend to agree with earlier research, specifically that immigrants

are not disproportion-

ately involved in crime and are oftentimes significantly less

involved than native-born

Americans (Hagan & Palloni, 1998; Martinez & Lee, 2000;

Mears, 2002; Rumbaut &

Ewing, 2007). Contemporary researchers examining the

immigrant-violent crime

nexus have concentrated their efforts on macro-level studies,

conducting both neigh-

borhood and city-level studies. Findings from macro-level

research surrounding the

immigration-violent crime question have been more inconsistent

than the individual-

level studies. There are a handful recent studies that find some

positive relationships

when examining the impact of immigration and certain crime](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/citizenshipstatusandarrestpatternsforviolentandnarcot-220921161002-4e0bb558/85/Citizenship-Status-and-Arrest-Patterns-for-Violentand-Narcot-6-320.jpg)