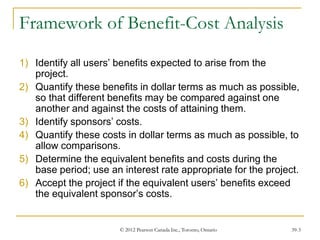

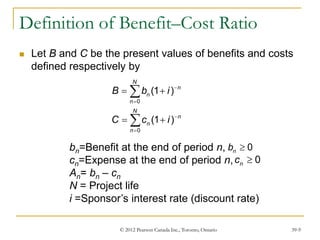

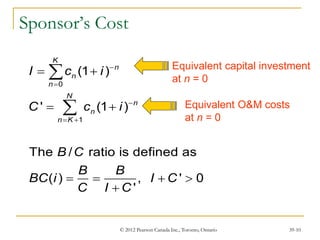

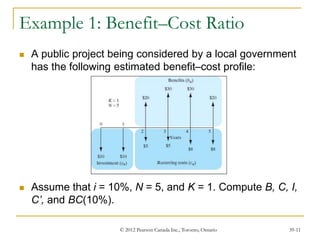

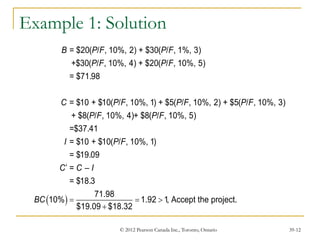

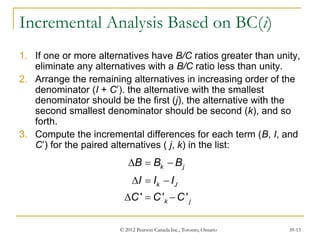

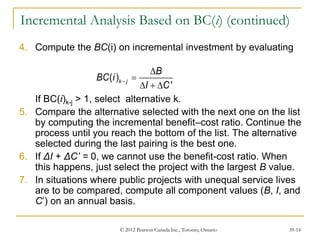

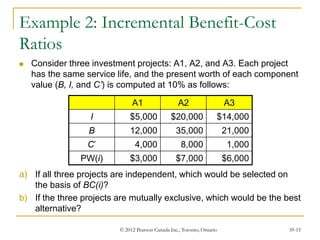

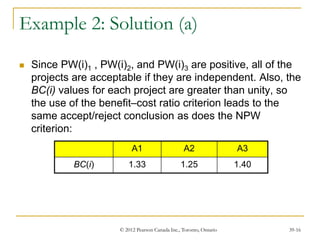

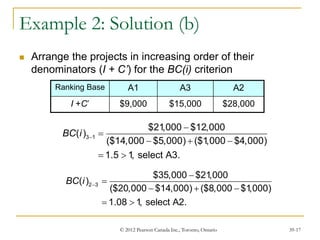

This document discusses benefit-cost analysis for evaluating public projects. It describes how to quantify both the benefits and costs of a project in monetary terms, calculate the present value of benefits and costs, and determine the benefit-cost ratio. A benefit-cost ratio above 1 indicates that the project's benefits outweigh its costs. The document also provides examples of how to calculate benefit-cost ratios and use incremental analysis to select between mutually exclusive projects.