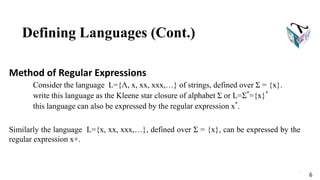

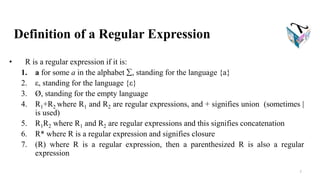

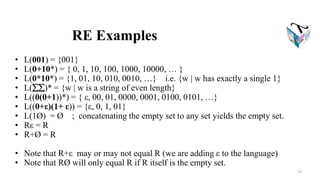

This document discusses regular expressions and provides examples. It begins by defining regular expressions recursively. Key points include:

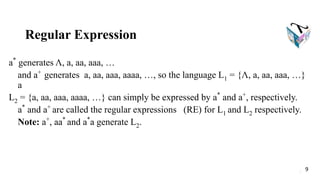

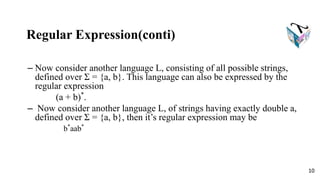

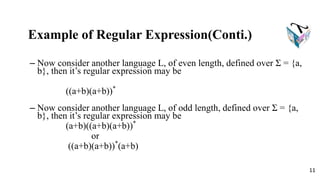

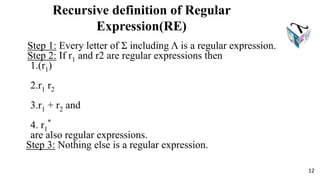

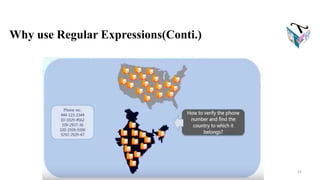

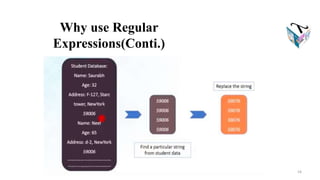

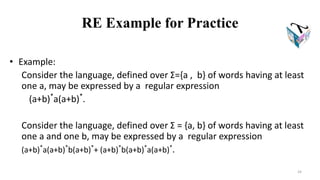

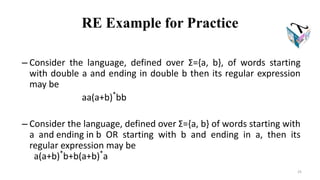

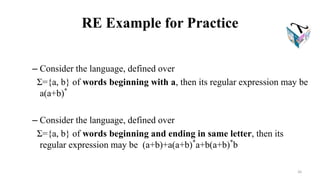

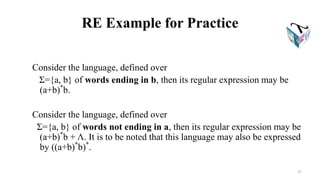

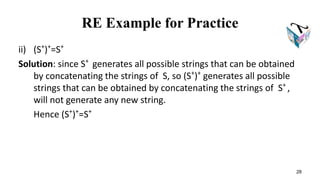

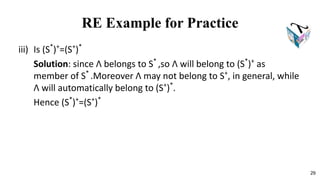

- Regular expressions can be used to concisely define languages. Common operations are concatenation, union, closure.

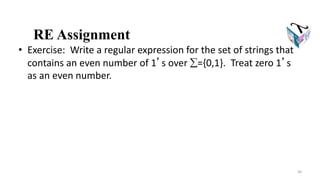

- Examples show how regular expressions can define languages with certain properties like having a single 1 or an even number of characters.

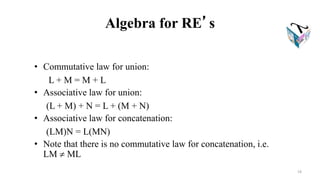

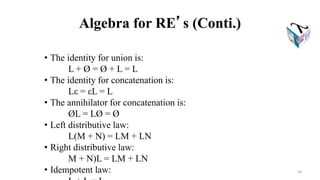

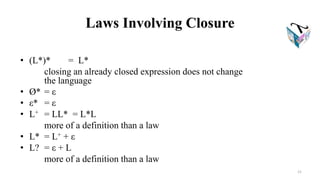

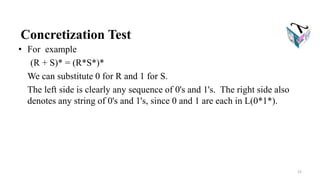

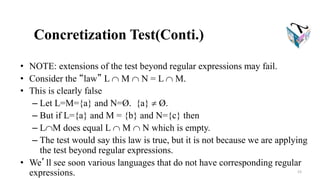

- Algebraic laws govern operations like distribution and idempotence for regular expressions. Concretization tests can verify proposed laws.