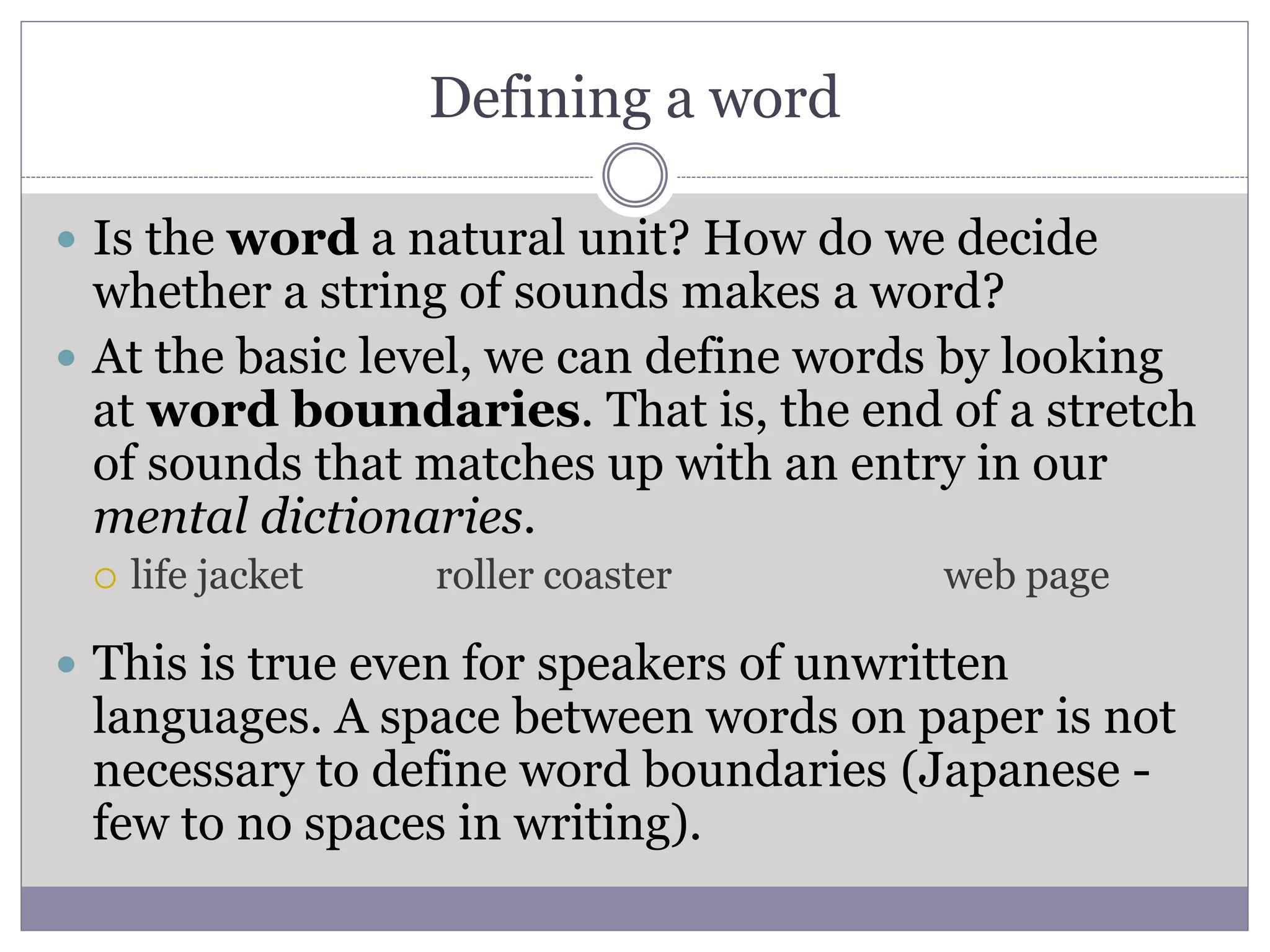

This document discusses different ways that new words can be created, including through acronyms, blending, and derivation. It notes that true coinages are rare and that new words must conform to a language's phonological and morphological rules. Acronyms are formed from the initial letters of words and can become lexicalized over time, such as HIV and laser. Backronyms are created by retrofitting an acronym's letters to real words. While word creation happens, most new words are formed based on existing linguistic elements in a language.

![Sounds and sequences

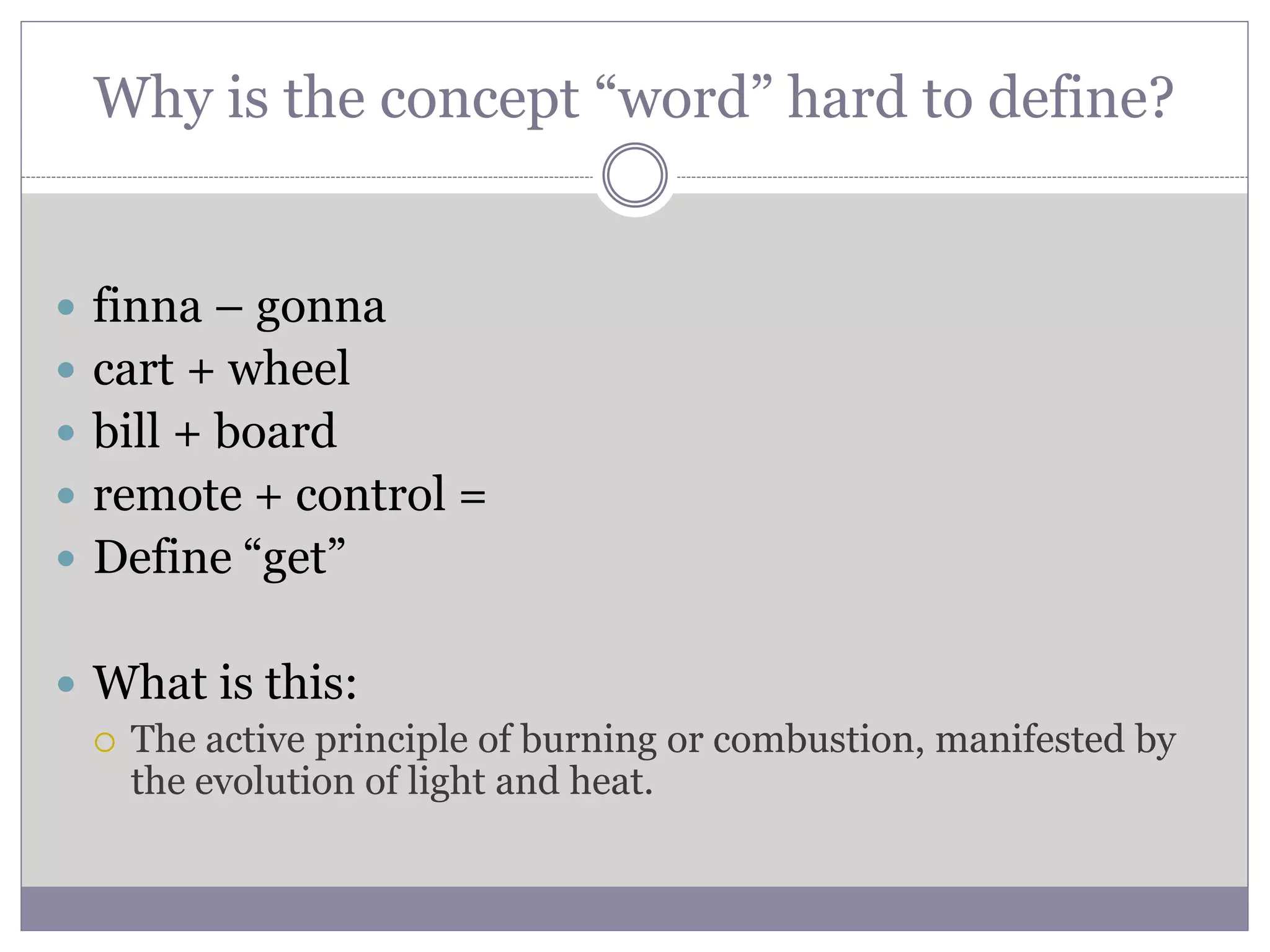

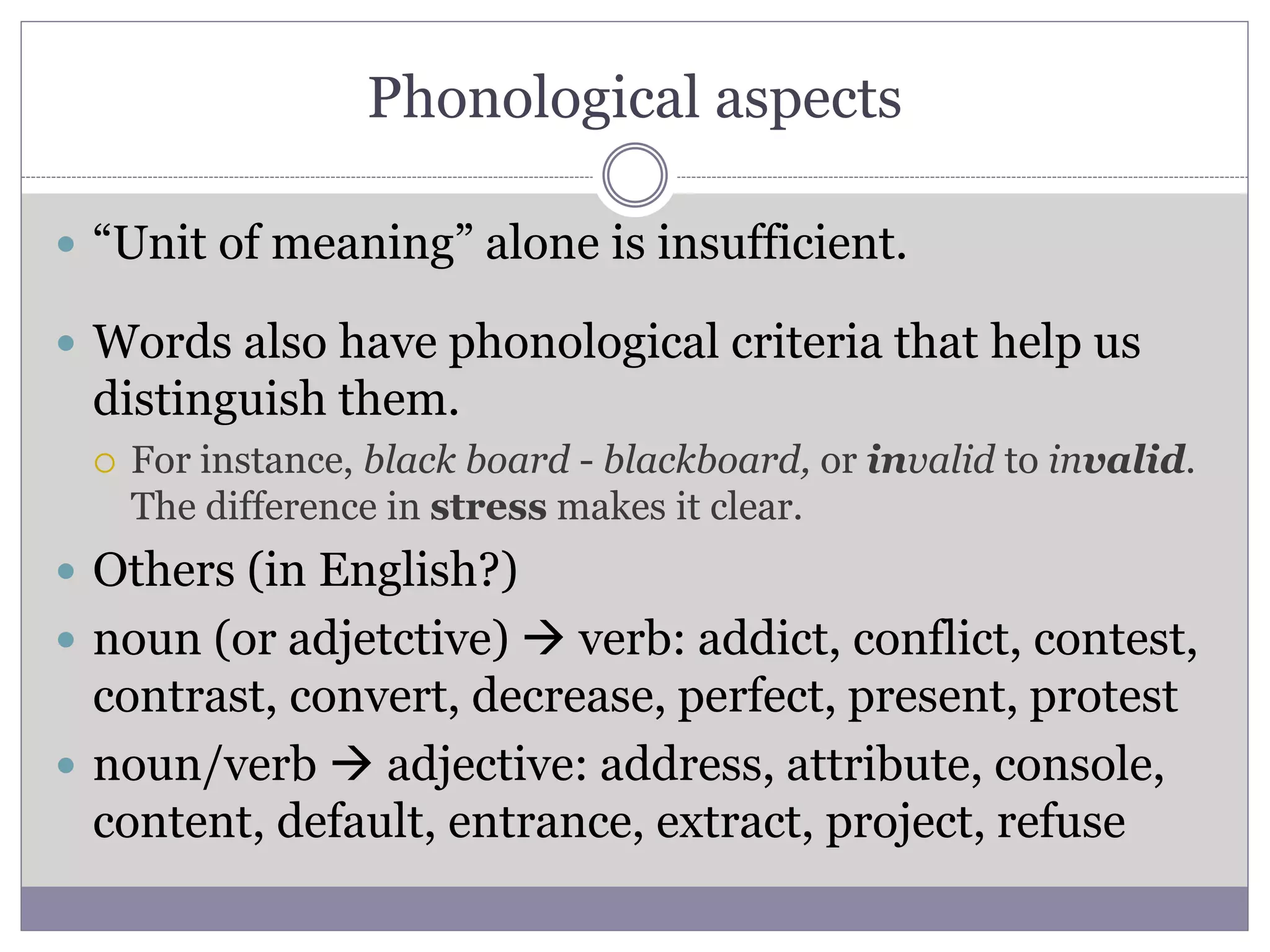

Other phonological properties deal with the

sounds/sound sequences that are allowed.

Some languages only permit certain consonants in

initial and final positions. For instance, in English

[kn] can appear at the end of a word (beckon), but

not at the beginning (we don’t pronounce the k in

knight or knee).

Speakers also often stop to think or correct

themselves while speaking in between word

boundaries (silence, ummm, errr).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4-230125212158-3ae47764/75/Chapter-4-1-pptx-17-2048.jpg)