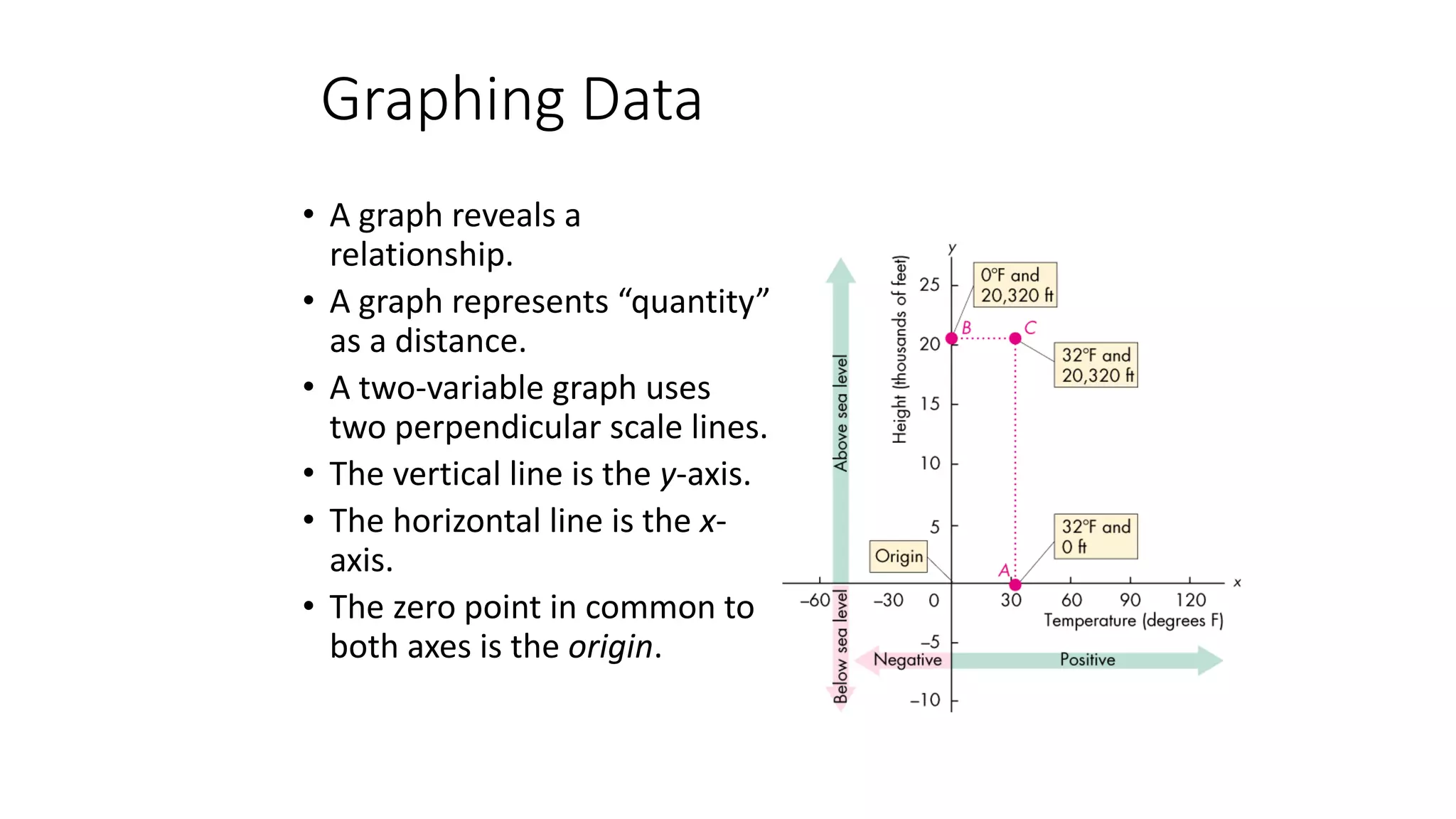

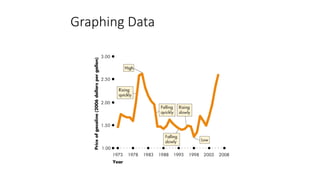

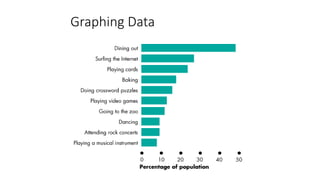

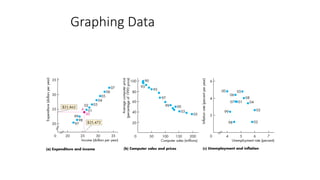

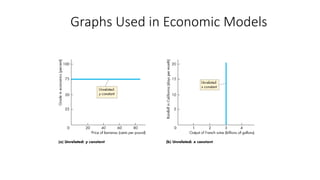

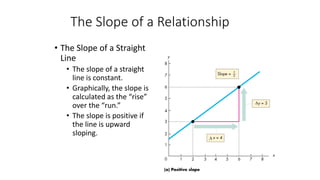

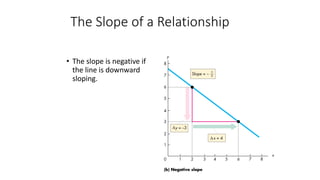

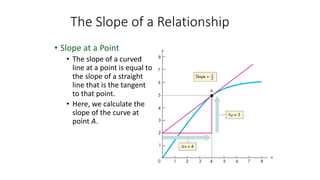

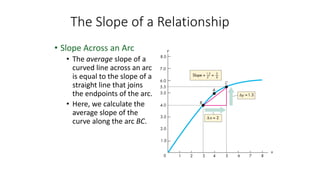

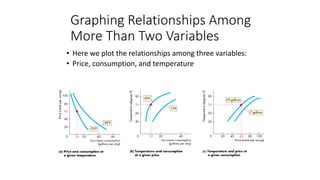

This document provides an overview of graphing data in economics. It discusses three main types of graphs used - time-series graphs, cross-section graphs, and scatter diagrams. Time-series graphs show a variable over time, cross-section graphs compare variables across groups, and scatter diagrams show the relationship between two variables. The document also discusses key graph elements like axes, trends, slopes, and using graphs to understand relationships between multiple variables.