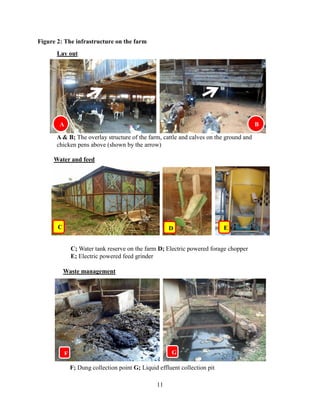

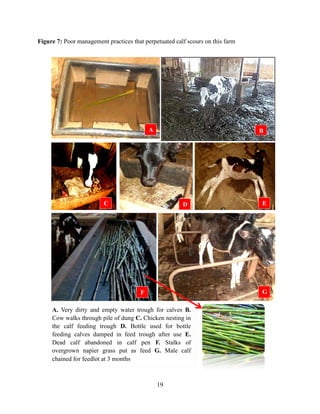

This document summarizes a case study on a zero grazing dairy farm in Uganda that was experiencing a high burden of calf scours. Through interviews and farm visits over 6 months, the study found a 32% prevalence and 14% mortality rate of calf scours on the farm. Poor housing conditions, hygiene, nutrition (insufficient feed and lack of water), and lack of training for farm workers were identified as key factors perpetuating the high incidence. Bacteriological analysis of fecal samples isolated Escherichia coli as the primary bacterial cause. The study concluded that improving biosecurity measures, sanitation, nutrition, and communication between management and workers could help reduce the burden of calf scours on the farm.

![24

Hudson, D., & White, R. G. (1975). G75-269 Calf Scours : Causes , Prevention and Treatment

Calf Scours : Causes , Prevention and Treatment.

Janovick, N. A., Boisclair, Y. R., & Drackley, J. K. (2011). Prepartum dietary energy intake

affects metabolism and health during the periparturient period in primiparous and

multiparous Holstein cows. Journal of Dairy Science, 94(3), 1385–400.

doi:10.3168/jds.2010-3303

Lassen, B., & Ostergaard, S. (2012). Estimation of the economical effects of Eimeria infections

in Estonian dairy herds using a stochastic model. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 106(3-4),

258–65. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2012.04.005

Lorenz, I., Fagan, J., & More, S. J. (2011). Calf health from birth to weaning. II. Management of

diarrhoea in pre-weaned calves. Irish Veterinary Journal, 64(1), 9. doi:10.1186/2046-0481-

64-9

Marsolais, G., Assaf, R., Montpetit, C., & Marois, P. (1978). Diagnosis of viral agents associated

with neonatal calf diarrhea.

, 42(2), 168–71. Retrieved from

http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1277610&tool=pmcentrez&ren

dertype=abstract

MARTIN, W. B., THOMAS, B. A. C., & URQUHART, G. M. (1957). Chronic diarrhoea in

housed cattle due to atypical parasitic gastritis. Veterinary Record, 69(31), 736–739.

Retrieved from

http://www.cabdirect.org/abstracts/19570801133.html;jsessionid=1FB57C7A697D6976A2

1B7F82E48F06EA

McAllister, T. A., Olson, M. E., Fletch, A., Wetzstein, M., & Entz, T. (2005). Prevalence of

Giardia and Cryptosporidium in beef cows in southern Ontario and in beef calves in

southern British Columbia.

Canadienne, 46(1), 47–55. Retrieved from

http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1082856&tool=pmcentrez&ren

dertype=abstract

Michna, A., Bartko, P., Bíres, J., Lehocký, J., & Reichel, P. (1996). [Metabolic acidosis in calves

with diarrhea and treatment with NaHCO3]. , 41(10), 305–10.

Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8975452

MONTSMA, G. (1960). Observations of milk yield, and calf growth and conversion rate, on

three types of cattle in Ghana. Tropical Agriculture, Trinidad and Tobago, 37, 293–302.

Retrieved from http://www.cabdirect.org/abstracts/19611403114.html

Mundt, H.-C., Bangoura, B., Rinke, M., Rosenbruch, M., & Daugschies, A. (2005). Pathology

and treatment of Eimeria zuernii coccidiosis in calves: investigations in an infection model.

Parasitology International, 54(4), 223–30. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2005.06.003

Ndambi, O. A., Garcia, O., Balikowa, D., Kiconco, D., Hemme, T., & Latacz-Lohmann, U.

(2007). Milk production systems in Central Uganda: a farm economic analysis. Tropical

Animal Health and Production, 40(4), 269–279. doi:10.1007/s11250-007-9091-4

Osoro, K., & Wright, I. A. (1992). The effect of body condition, live weight, breed, age, calf

performance, and calving date on reproductive performance of spring-calving beef cows.

Journal of Animal Science, 70(6), 1661–1666. doi:/1992.7061661x

Practice, G. V., & Health, A. (2003). Calf Scours in Southern. October, (October).

Reynolds, W. L., Urick, J. J., & Knapp, B. W. (n.d.). Biological type effects on gestation

length, calving traits and calf growth rate. Journal of Animal Science, 68(3), 630–639.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6935e610-7bbd-4f33-b1dd-f1a6d9faa22a-160125040306/85/Calf-scours-final-35-320.jpg)