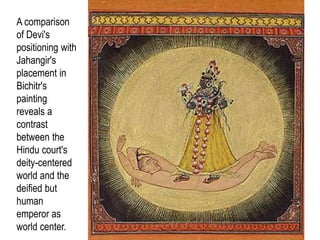

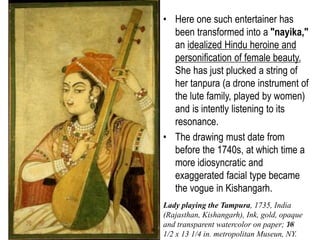

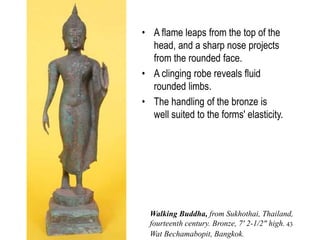

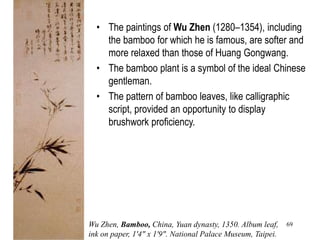

The document explores the art and cultural developments in India and Southeast Asia, highlighting significant shifts in religious and political contexts, particularly the influences of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam. It discusses key artistic traditions, including Hindu temples and Mughal architecture, along with notable artifacts and paintings that reflect the region's spiritual and artistic heritage. The text emphasizes the enduring legacy of these artistic movements and their impact on wider cultural practices throughout history.

![85

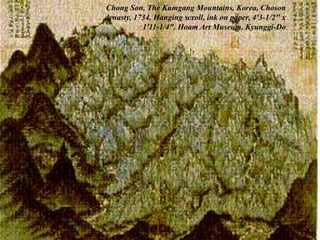

Autumn Mountain

The mountain colors are

a hoary green, the trees

are turning autumnal,

A yellowish mist rises thinly

against a rushing stream;

In a traveler's lodge,

Bitter Melon [Shitao] passes

his time with a brush,

His painting method ought

to put old Guanxiu to

shame.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c25-150103082349-conversion-gate02-240529103511-2fb3af72/85/c25-150103082349-conversion-gate0002-ppt-85-320.jpg)