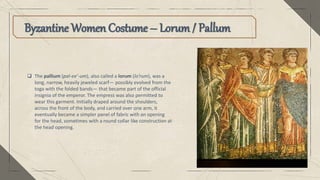

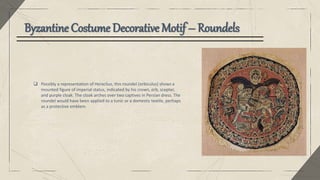

The document provides an overview of Byzantine civilization, highlighting its historical timeline, social classes, and cultural elements such as art, clothing, and jewelry. Key events include the relocation of the capital to Byzantium by Constantine in 330, the empire's expansion under Justinian, and the eventual fall to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. Additionally, it discusses the significance of silk production and the evolution of clothing styles for both men and women during this period.

![ Justinian I, Latin in full Flavius Justinianus, original name Petrus

Sabbatius, (born 483, Tauresium, Dardania [probably near

modern Skopje, North Macedonia]—died November 14,

565, Constantinople [now Istanbul,

Turkey]), Byzantine emperor (527–565), noted for his

administrative reorganization of the imperial government and for

his sponsorship of a codification of laws known as the Code of

Justinian (Codex Justinianus; 534).

Emperor Justinian](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/byzantinecivilizationpresentation-201220201123/85/Byzantine-civilization-presentation-19-320.jpg)