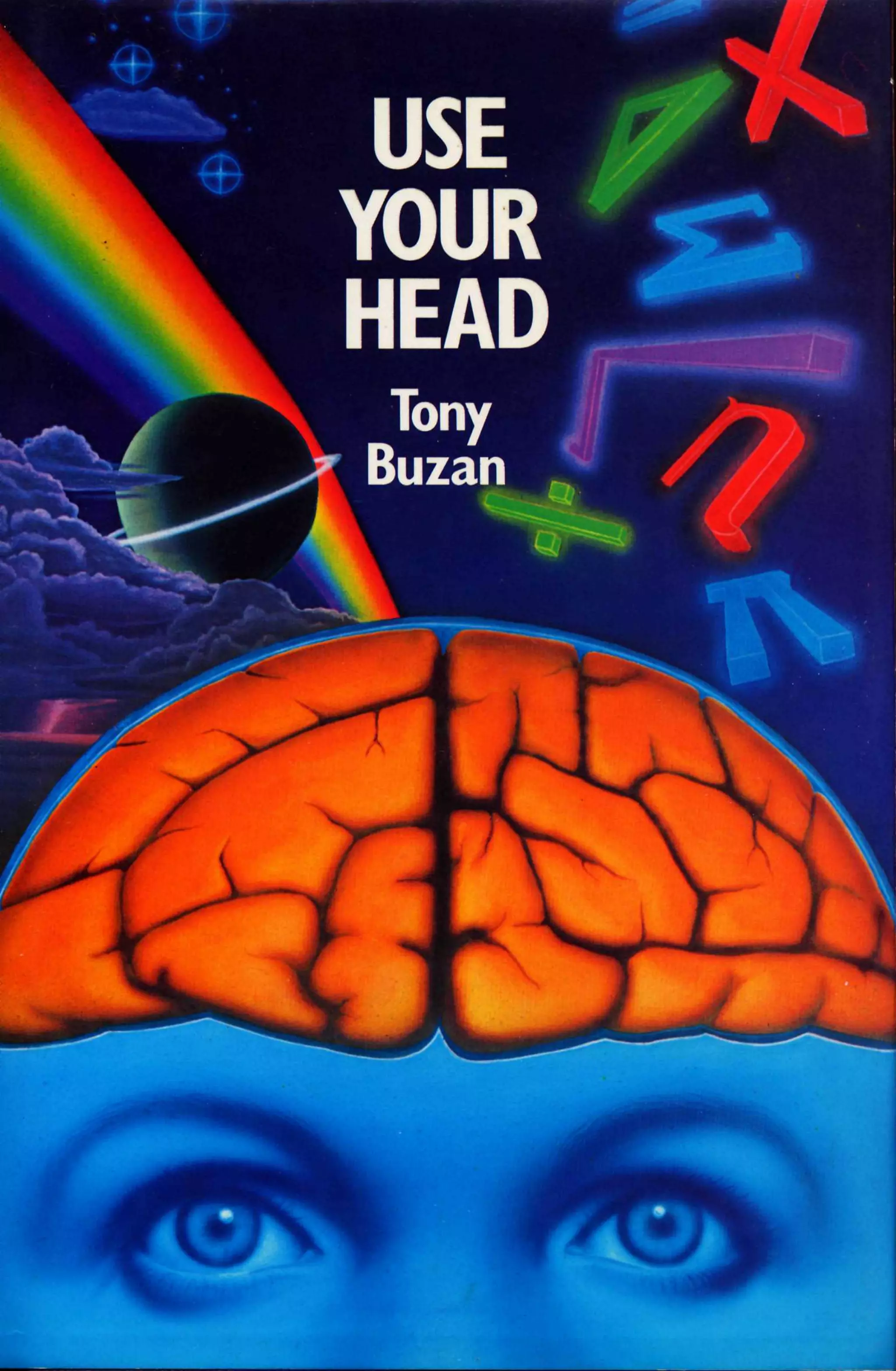

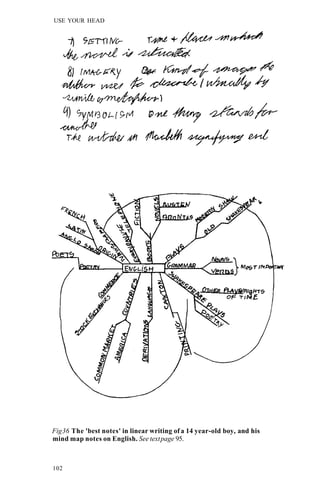

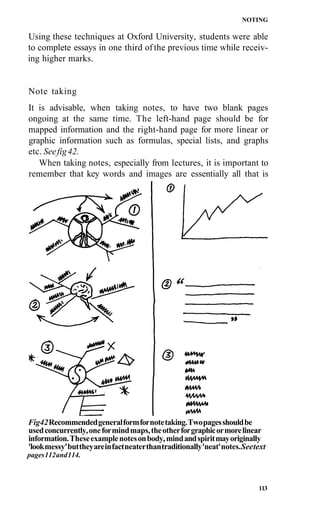

This chapter discusses recent discoveries about the true capabilities of the human brain and how people are able to realize and develop abilities that normally lie dormant. It explains that modern research has led to a much greater understanding of how the brain works in just the past 10-15 years. The brain has abilities that far exceed what IQ tests measure. Even very young babies demonstrate high-level cognitive skills, showing the brain's tremendous potential that is not fully tapped.