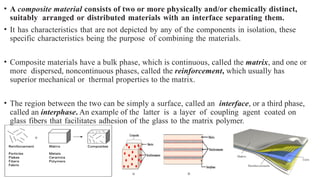

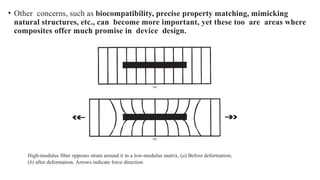

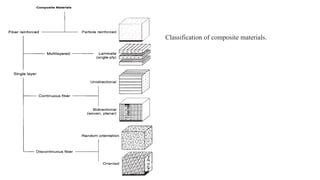

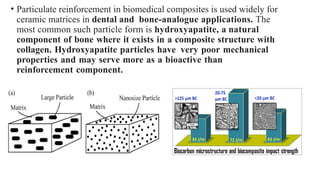

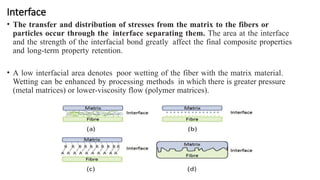

The document explains biocomposites as composite materials consisting of a matrix and reinforcement phases, highlighting their enhanced mechanical properties compared to isolated components. It categorizes composites based on the matrix material and details fiber-reinforced and particle-reinforced composites, emphasizing the influence of component arrangement and interactions on performance. Furthermore, it discusses processing methods, physical properties, biological responses, and various biomedical applications such as orthopedic and dental uses.