The document presents a BIM-integrated framework aimed at predicting schedule delays in modular construction, highlighting the critical issues of project delays and the potential of technology in mitigating these risks. It provides a structured methodological approach using data analytics within a framework aligned with the lean six sigma process, facilitating data-driven decision-making in construction management. The research addresses gaps in quantitative risk management techniques and emphasizes the importance of leveraging operational data for improved scheduling outcomes.

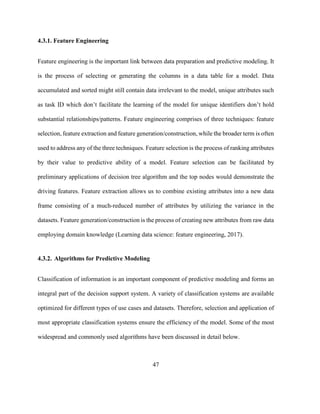

![78

Cells.FormatConditions.Delete

End Sub

#3 Close the open sheets

Sub CloseBooks()

Windows("case1_withschedule data.xlsx").Activate

Application.DisplayAlerts = False

ActiveWorkbook.Close

Windows("case2_withschedule data.xlsx").Activate

Application.DisplayAlerts = False

ActiveWorkbook.Close

Windows("case3_withschedule data.xlsx").Activate

Application.DisplayAlerts = False

ActiveWorkbook.Close

Windows("case4_withschedule data.xlsx").Activate

Application.DisplayAlerts = False

ActiveWorkbook.Close

End Sub

#4 Calculate duration and delay

Sub check_delay()

If Range("d6").Value = "" Then

MsgBox ("please copy the data")

Else

'To Claculate Which ever is greater days

Range("A1").Select

Selection.End(xlDown).Select

Selection.End(xlDown).Select

Selection.End(xlToRight).Select

ActiveCell.Offset(0, 1).Range("A1").Select

Selection.End(xlUp).Select

ActiveCell.Offset(1, 0).Range("A1").Select

ActiveCell.FormulaR1C1 = "=IF((RC[-6]-RC[-5])>(RC[-4]-RC[-

3]),(RC[-6]-RC[-5]),(RC[-4]-RC[-3]))"

Range("A1").Select

Selection.End(xlDown).Select

Selection.End(xlDown).Select

Selection.End(xlToRight).Select

ActiveCell.Offset(0, 1).Range("A1").Select

Range(Selection, Selection.End(xlUp)).Select

ActiveCell.FormulaR1C1 = ""

Selection.FormulaR1C1 = "=IF((RC[-6]-RC[-5])>(RC[-4]-RC[-

3]),(RC[-6]-RC[-5]),(RC[-4]-RC[-3]))"

'To Calculate Duration](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalreport-171112222604/85/BIM-Integrated-predictive-model-for-schedule-delays-in-Construction-88-320.jpg)

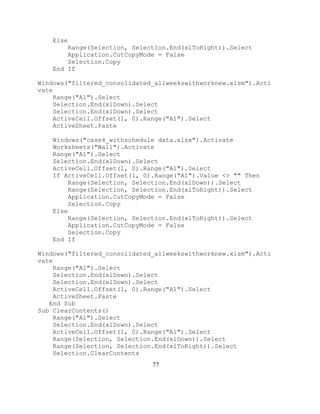

![79

Range("A1").Select

Selection.End(xlDown).Select

Selection.End(xlDown).Select

Selection.End(xlToRight).Select

ActiveCell.Offset(0, 1).Range("A1").Select

Selection.End(xlUp).Select

ActiveCell.Offset(1, 0).Range("A1").Select

ActiveCell.FormulaR1C1 = "(RC[-7]-RC[-5])"

Range("A1").Select

Selection.End(xlDown).Select

Selection.End(xlDown).Select

Selection.End(xlToRight).Select

ActiveCell.Offset(0, 1).Range("A1").Select

Range(Selection, Selection.End(xlUp)).Select

ActiveCell.FormulaR1C1 = ""

Selection.FormulaR1C1 = "=(RC[-7]-RC[-5])"

End If

End Sub](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalreport-171112222604/85/BIM-Integrated-predictive-model-for-schedule-delays-in-Construction-89-320.jpg)