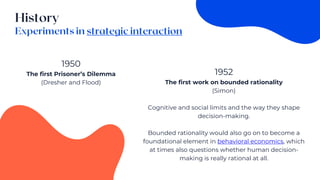

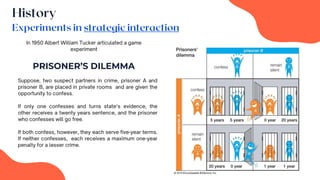

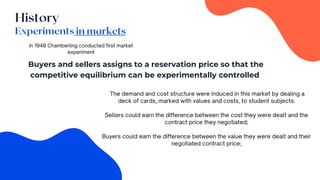

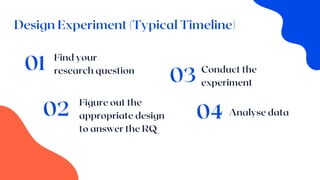

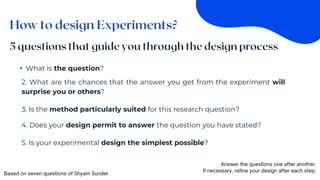

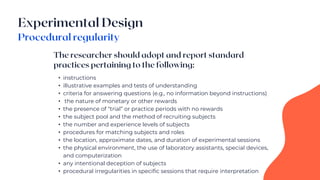

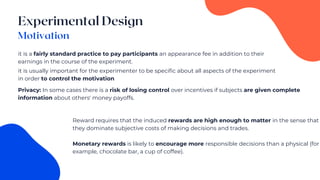

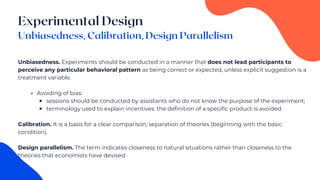

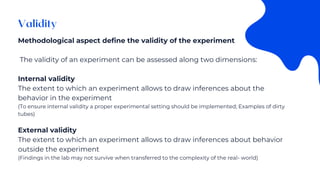

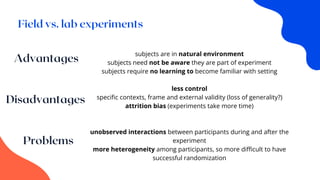

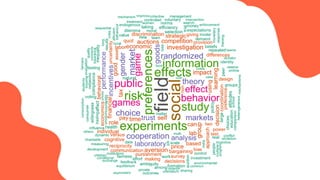

The document discusses the history and design of economic experiments. It notes that early experiments explored individual decision making, strategic interaction, and markets. Key developments included testing indifference curves and expected utility theory in the 1940s-1950s. The document outlines important considerations for experimental design such as questions, validity, field vs lab settings, and criteria for unbiasedness, calibration, and procedural regularity. It emphasizes the importance of control and standardization in experimental procedures to facilitate replication.