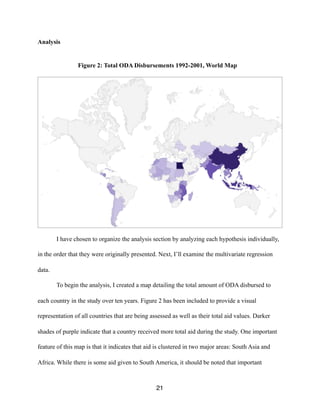

This study examines the relationship between multilateral aid allocations from the OECD and levels of government respect for human rights from 1992-2001. Specifically, it tests two hypotheses: 1) That ODA has a direct positive effect on human rights scores, and 2) That ODA has an indirect effect on human rights by positively impacting regime type and economic development, which are known to positively impact human rights. The study uses data from the OECD, World Bank, Polity IV Project, and Cingranelli-Richards Human Rights Data Set to conduct statistical analyses, including regression models. Preliminary results indicate that while regime type and economic development are positively associated with human rights, ODA allocations have a negative impact

![rights scores is an indirect one, using opportunity cost logic; Gibler argues that because foreign

aid allocations are made public each year, countries with poor human rights “are quite aware of

the monies lost due to repressive human rights practices” (Gibler 2008, 513). This has interesting

implications for this hypothesis because it does show that it is possible that foreign aid has an

indirect effect on human rights. Like others, Gibler works with the assumption that monies are

allocated based on level of respect for human rights by the country. This once again bases levels

of aid on human rights scores instead of human rights scores being affected by levels of aid.

However, the results of his study indicate that “U.S. aid does positively affect human rights

policies abroad” (Gibler 2008, 514). Surprisingly, it is not the allocation of foreign aid that

changes human rights behavior, but the absence of foreign aid. In other words, repressive

governments that do not receive foreign aid modify their behavior after viewing the opportunity

cost of their disrespect for human rights. At the 1993 Vienna Conference, United Nations

members agreed that “there was substantial consensus [that]…democracy, development and

respect for human rights were all pronounced ‘interdependent and mutually

reinforcing’”(UNHCR 1993). This also lends support to the theory that as democracy and levels

of development increase, respect for human rights should also increase.

Richards, Gelling and Sacko’s 2001 study examined the relationship between

development assistance and human rights along with the the relationship between human rights

and other variables such as democracy and economic development and reached the following

conclusion:

“Both models fail to provide evidence that official development assistance influences

government support for human rights. The fact that we found aid to be consistently

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20aaf549-429f-43bb-97b0-ea4f898c26ab-161119173537/85/Bates-Capstone-6-320.jpg)

![economic development, ODA allocations are awarded with the goal of creating “effective,

democratic and accountable governance [and] the protection of human rights” (DAC 1996, 2).

ODA and human rights: A Direct Relationship

The Deputy Secretary of State in the Carter Administration, Cyrus Vance testified before

the House Committee of Foreign Affairs stating that “foreign assistance programs are an

essential tool in promoting a broad category of internationally recognized human rights” (Regan,

1995, 615). Another way to view this relationship is using the common “carrot and stick”

analogy which states that when attempting to change the behavior of an individual or a country,

the one who seeks change has two options. They can dangle a carrot, an incentive in front of the

country that they wish to modify, or beat them with a stick, in other words punishing them with

the hopes of forcing them into cooperation. Following that logic, a target country should prefer a

reward over punishment and opt to change their human rights practices in return for a reward

over being punished. In practice this is called aid conditionality, which USAID defines as “an

exchange of policy reforms for external resources.” and is “based on the premise that financial

aid works best in a sound policy environment” (Spevacek 2010, 2). Though aid conditionality

was deemed a failure by the OECD in the mid to late 2000’s, it was a common form of economic

reform in the 80’s and 90’s (Mold, Zimmerman, 2008, 1). Given the premise regarding financial

aid, and the prevalence of aid conditionality during the time period being examined, the first

hypothesis examined will examine the direct relationship between ODA and human rights.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20aaf549-429f-43bb-97b0-ea4f898c26ab-161119173537/85/Bates-Capstone-9-320.jpg)

![Findings surrounding the effect of aid on economic development are mixed. Therefore it

is unclear whether or not aid will produce positive economic effects. While the OECD suggests

that its “Aid For Trade” program is showing promising results, working papers published by the

International Monetary Fund conclude that “certain types of foreign aid do positively impact

[economic] development though they are unable to determine what types of aid have that

impact” (Minoiu, Sanjay 2009). While no causal mechanism has been identified, constant

reference to the mysterious relationship warrants further investigation.

As a result of the potential indirect relationships between ODA and human rights, four

more hypotheses emerge to be tested, followed by Figure 1, which visually links the hypotheses

with one another.

Hypothesis 2: When comparing the relationship between regime type and human rights

scores, democracy has a positive effect on human rights from 1992-2001. Research indicates that

as countries become more democratic, they have a greater respect for human rights (Howard,

Donnelly 1986). One of the reasons that this occurs can be explained by the selectorate theory

which is described in The Logic of Political Survival. The selectorate theory states that three

groups of people affect leaders: the nominal selectorate, the real selectorate and the winning

coalition (Mesquita, Smith, Siverson, Morrow, 2003). The nominal selectorate is every

individual in a country that has a say in choosing a leader, the real selectorate are the individuals

who choose the leader, and the winning coalition is everyone who supports the winning leader.

The selectorate theory states that the primary goal of a leader is to remain in power, by retaining

the winning coalition. In order to retain the winning coalition, leaders must respond to their

needs and in democracies, the winning coalition is much larger and more diverse than it is in an

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20aaf549-429f-43bb-97b0-ea4f898c26ab-161119173537/85/Bates-Capstone-12-320.jpg)